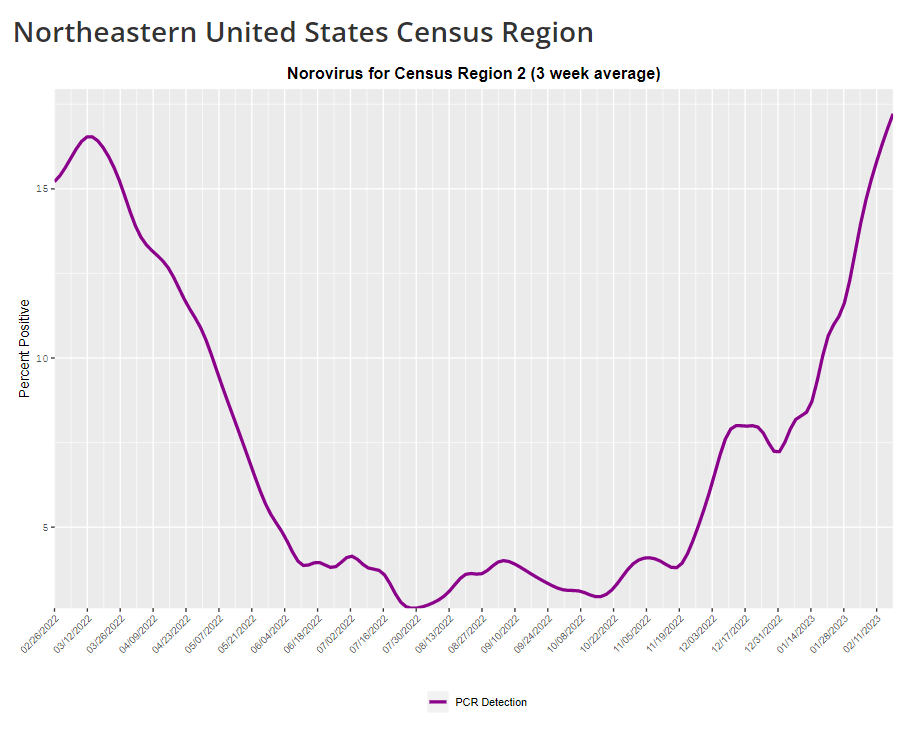

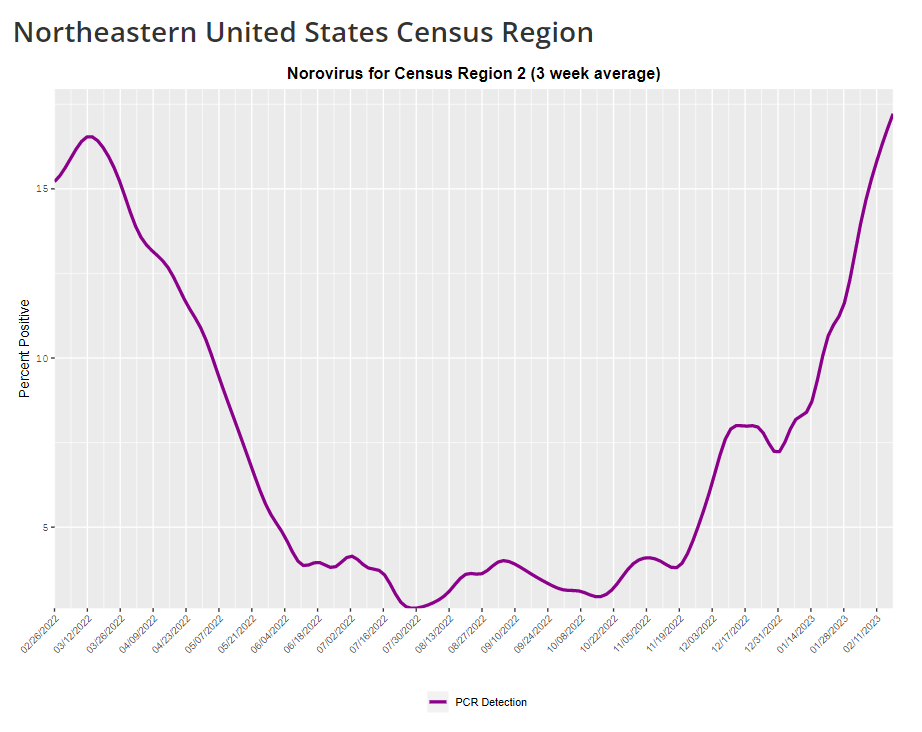

This week, I have a new story out in Gothamist and WNYC (New York City’s public radio station) about norovirus, a nasty stomach bug that appears to be spreading a lot in the U.S. right now. The story shares some NYC-specific norovirus information, but it also talks more broadly about why it’s difficult to find precise data on this virus despite its major implications for public health.

Reporting this story led me to reflect on how COVID-19 has revealed cracks in the country’s infrastructure for tracking a lot of common pathogens. I’ve written previously about how the U.S. public health system monitored COVID-19 more comprehensively than any other disease in history; the scale of testing, contact tracing, and innovation into new surveillance technologies went far beyond the previous standards. Now, people who’ve gotten used to detailed data on COVID-19 have been surprised to find out that such data aren’t available for other common pathogens, like the flu or norovirus.

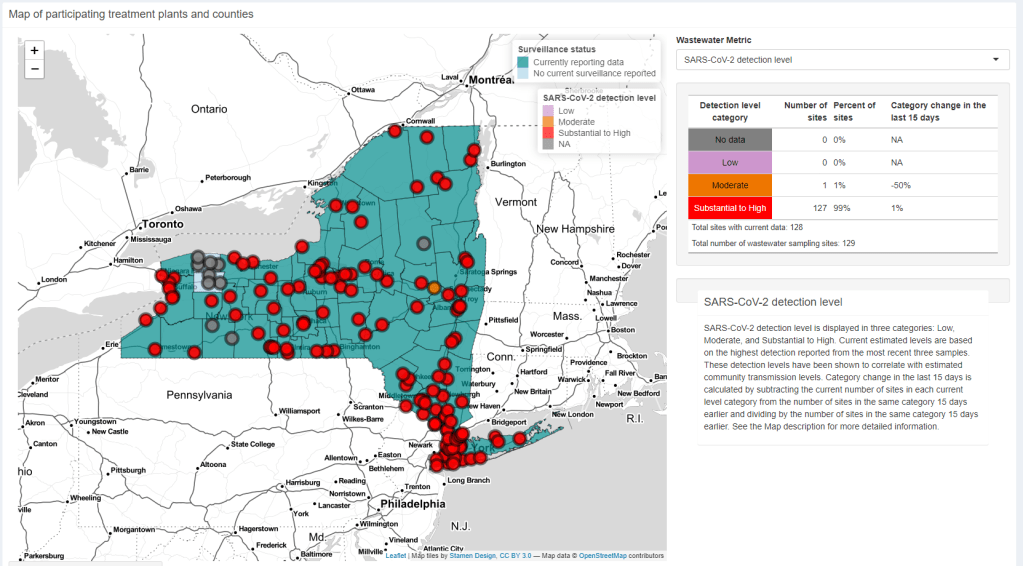

It might feel disappointing to realize how little we actually know about the impacts of endemic diseases. But I choose to see this as an opportunity: as COVID-19 revealed gaps in public health surveillance, it inspired development in potential avenues to close those gaps. Wastewater surveillance is one big example, along with the rise of at-home tests and self-reporting mechanisms, better connectivity between health systems, mobility data, exposure notifications, and more.

Norovirus is a good example of this trend. Here are a few main findings from my story:

- Norovirus is a leading cause of gastrointestinal disease in the U.S., and is estimated to cause billions of dollars in healthcare and indirect societal costs every year.

- People who become infected with norovirus are often hesitant to seek medical care, because the symptoms are disgusting and embarrassing. Think projectile vomit, paired with intense diarrhea.

- Even when patients do seek medical care, norovirus tests are not widely available, and there isn’t a ton of incentive for doctors to ask for them. Testing usually requires a stool sample, which patients are often hesitant to do, one expert told me.

- The virus is not a “reportable illness” for the CDC, meaning that health agencies and individual doctors aren’t required to report norovirus cases to a national monitoring system. (So even when a patient tests positive for norovirus, that result might not actually go to a health agency.)

- The CDC does require health agencies and providers to report norovirus outbreaks (i.e. two or more cases from the same source), but national outbreak estimates are considered to be a vast undercount of true numbers.

- Even in NYC, where the city’s health agency does require reporting of norovirus cases, there’s no recent public data from test results or outbreaks. (The latest data is from 2020.)

As I explained in an interview for WNYC’s All Things Considered, the lack of a national reporting requirement and other challenges with tracking norovirus are linked:

It seems like the lack of a requirement and the difficulty of tracking kind-of play into each other, where it’s not required because it’s hard to track—but it’s also hard to track because it’s not required.

The lack of detailed data on pathogens like norovirus can be frustrating on an individual level, for health-conscious people who might want to know what’s spreading in their community so that they can take appropriate precautions. (For norovirus, precautions primarily include rigorous handwashing—hand sanitizer doesn’t work against it—along with cleaning surfaces and care around food.)

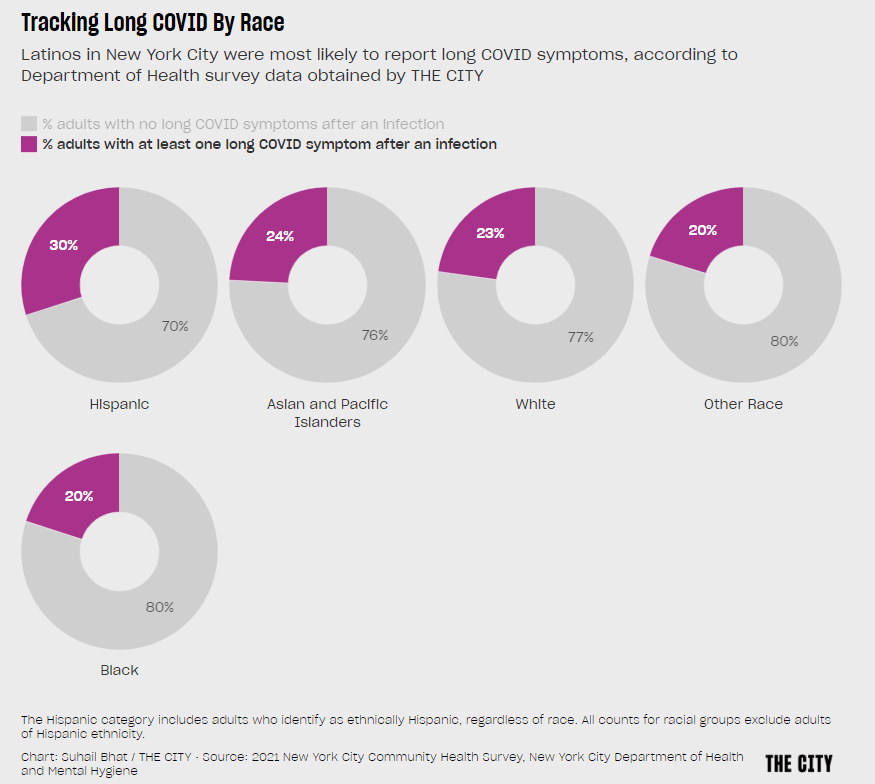

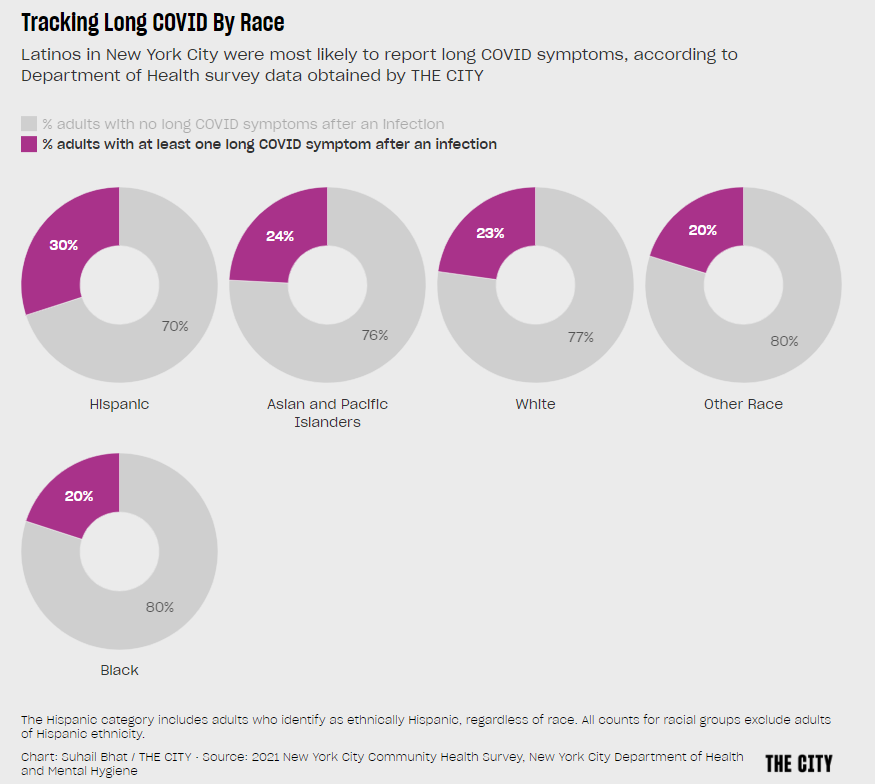

These data gaps can also be a challenge for public officials, as more detailed information about where exactly a virus is spreading or who’s getting sick could inform specific public health responses. For example, if the NYC health department knew which neighborhoods were seeing the most norovirus, they could direct handwashing PSAs to those areas. In addition, scientists who are developing norovirus vaccines could use better data to estimate the value of those products, and determine who would most benefit.

So, how do we improve surveillance for norovirus and other viruses like it? Here are a few options I found in my reporting:

- Wastewater surveillance, of course. The WastewaterSCAN project is already tracking norovirus along with coronavirus and several other common viruses; its data from this winter has aligned with other sources showing a national norovirus surge, one of the project’s principal investigators told me.

- Better surveillance based on people’s symptoms. The Kinsa HealthWeather project offers one example; it aggregates anonymous information from smart thermometers and a symptom-tracking app to provide detailed data on respiratory illnesses and stomach bugs.

- At-home tests, if they’re paired with a mechanism for people to report their results to a local public health agency. Even without a reporting mechanism, at-home tests could help curb outbreaks by helping people recognize their illness when they might be asymptomatic.

- Simply increasing awareness and access to the tests that we already have. If more people go to the doctor for gastrointestinal symptoms and more doctors test for norovirus, our existing data would get more comprehensive.

Are there other options I’ve missed? Is there another pathogen that might be a good example of common surveillance issues? Reach out and let me know.