We are in an era of dashboard shutdowns. Government agencies, research groups, and media organizations alike are winding down their COVID-19 reporting efforts. Some of these changes are directly tied to the end of the federal public health emergency in May, while others are more broadly attributed to shifting resources.

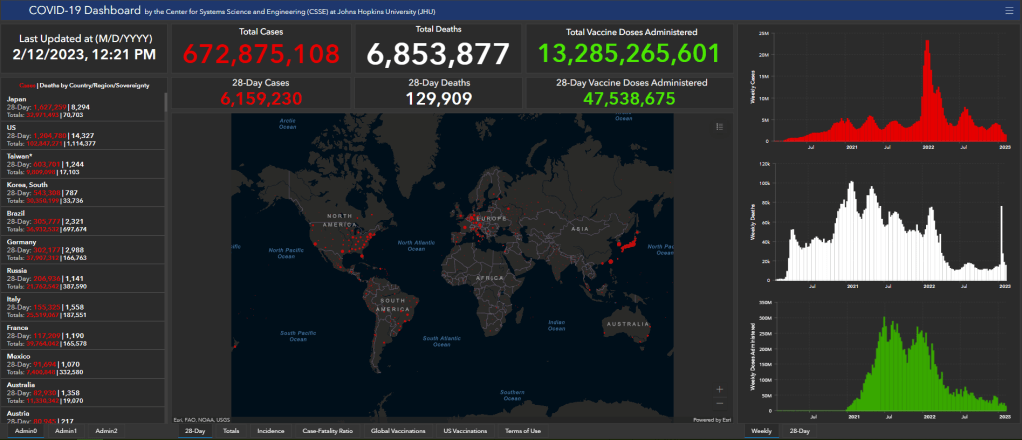

In the last couple of weeks alone: the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 dashboard stopped collecting new data, the New York Times switched its COVID-19 tracker to show CDC data instead of compiling original information from states and counties, and the CDC itself announced that its COVID-19 data newsletter will end in May. The White House COVID-19 team will also be disbanded in May, according to reporting from the Washington Post.

I haven’t done a comprehensive review of state and local COVID-19 dashboards, but I’m sure many of those are similarly shutting down, reporting less frequently, and reducing the types of data that they offer to the public. This is a trend I’ve been following since early last year, when state health departments started to declare COVID-19 was now “endemic” and didn’t require special monitoring resources, PCR testing infrastructure, etc. But it’s been accelerating in recent weeks, following the White House announcement about the end of the federal emergency.

When explaining why their COVID-19 reporting efforts are ending, organizations often state that the disease is “no longer a major threat” or say that public interest in tracking COVID-19 has waned. I’m skeptical about both of those claims. First of all, we know that COVID-19 is still killing hundreds of Americans each week, with a majority of those being people who have had multiple vaccine doses. And we know that millions are facing activity limitations from Long COVID. As I wrote last month, the U.S. didn’t have a “mild” winter this year; we’re just getting better at ignoring COVID-19’s continued impacts.

And second of all, I know there’s still an audience for this work—including many of the people who remain most vulnerable to COVID-19. Thank you to everyone who regularly reads this newsletter and blog, sends me questions, shares my work on social media, etc. for constantly validating that the interest is still here.

With all of you great readers in mind, I’ve compiled this list of COVID-19 dashboards that I know haven’t yet shut down. The list is focused on national sources rather than state/local or international ones, in the interest of being most helpful to the majority of readers.

- CDC COVID Data Tracker: The CDC’s COVID-19 dashboard is, of course, the primary source for federal data at this point in the pandemic. It provides weekly updates for most metrics (cases, hospitalizations, deaths, vaccinations, variant estimates, etc.); wastewater surveillance data are updated daily, with individual testing sites reporting on different cadences (usually about twice per week).

Post-PHE update: Still active, but greatly changed. Cases and testing metrics are no longer available (with testing labs and state/local health agencies no longer required to report to the CDC), while other key metrics are updated less frequently or with more of a delay. See this post for more details. - Census Household Pulse Survey: Since early in the pandemic, the U.S. Census’ Household Pulse Survey has provided data on how COVID-19 impacted Americans’ day-to-day lives. This survey’s most recent iteration is scheduled for March through May 2023. The Census collaborates with other federal agencies on its surveys, including the CDC for Long COVID questions.

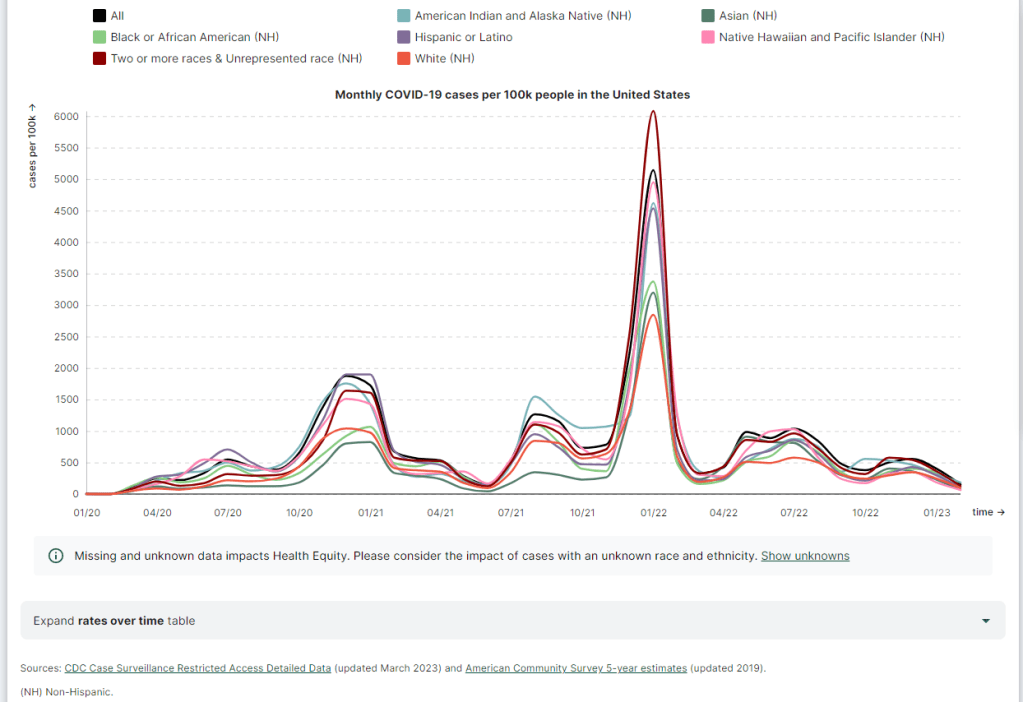

Post-PHE update: The Pulse survey is typically conducted in two-month installments, with several weeks between each installment to adjust questions and process data. Its most recent installment ended in early May, and the next one has yet to be announced; we should know within the next month whether this data source is ending with the PHE or if it will continue. - Morehouse Health Equity Tracker: This project, from the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine, tracks COVID-19 metrics and a variety of other health conditions by race and ethnicity. The COVID-19 data are based on a CDC restricted access dataset; updates will continue “for as long as the CDC gives us data,” software engineer Josh Zarrabi said on Twitter this week.

Post-PHE update: For COVID-19 data, this tracker utilizes a CDC dataset of cases with detailed demographic information, compiled from case reports sent to the CDC by state health agencies. The CDC dataset was last updated in April 2023, and it’s unclear whether it’ll be updated again (but my guess is it’ll end with the PHE). The Morehouse tracker includes plenty of other health metrics, though, so I expect this dashboard will be able to adjust to the CDC change. - APM Research Lab: This research organization, run by American Public Media, has several ongoing COVID-19 trackers. These include COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity (national and by state), vaccination rates (national and by state), and Minnesota-specific data, in collaboration with Minnesota Public Radio.

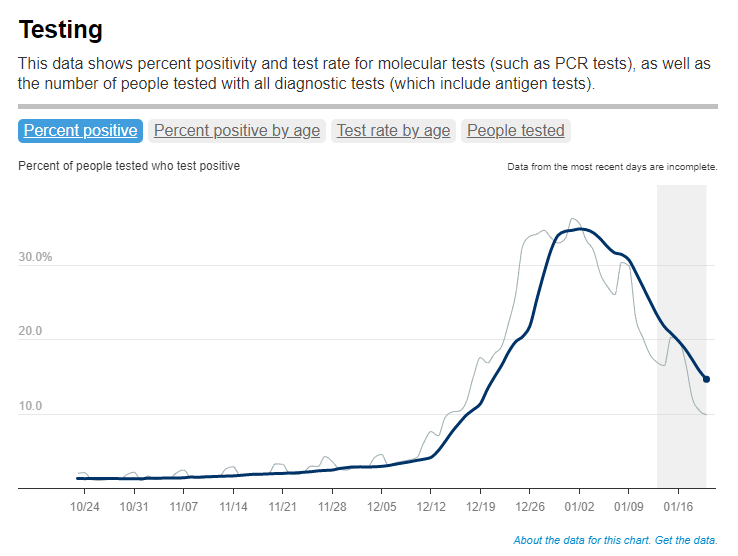

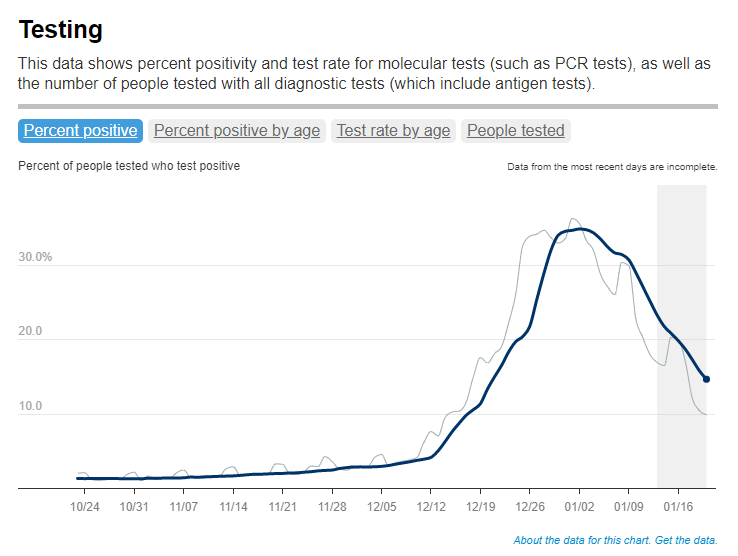

Post-PHE update: APM is continuing to update its tracker; the most recent update to its COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity page occurred on May 17. Its staff will likely need to make some changes to their underlying data sources, since the CDC is now reporting COVID-19 deaths differently, but the basic metrics remain available. - Walgreens COVID-19 Index: Walgreens shares data from COVID-19 tests conducted at over 5,000 pharmacy locations nationwide. The tracker includes test positivity (national trends and state-by-state), variant prevalence, and positivity by vaccination status.

Post-PHE update: Still active, with no change due to the PHE’s end. - COVIDcast by CMU Delphi: COVIDcast is a COVID-19 monitoring project by the Delphi Group at Carnegie Mellon University. The dashboard pulls in COVID-19 data from the CDC and other sources, such as Google search trends and antigen test positivity.

Post-PHE update: No longer includes cases and deaths (which were pulled from the CDC), but still updating other metrics, including hospital admissions, symptom searches from Google trends, and COVID-related doctor visits. - Iowa COVID-19 Tracker: Despite its name, the Iowa COVID-19 Tracker displays data from across the country, sourced from the CDC. It’s run by Sara Anne Willette, a data expert based in Ames, Iowa. Willette frequently shares data updates on social media and streams on Twitch when updating her dashboard.

Post-PHE update: Still active, but with some changes due to the new limitations in CDC data. Dashboard manager Sara Anne Willette shares frequent updates on Twitter about what she’s changing and why. - COVID-19 dashboard by Jason Salemi: This dashboard by University of South Florida epidemiologist Jason Salemi is another page displaying CDC data in somewhat-more-user-friendly visualizations. The dashboard is focused on Florida, but shares national state- and county-level data.

Post-PHE update: Salemi shared on Twitter last week that he is currently assessing whether to keep the dashboard running or decomission the site. - Biobot Analytics: Biobot Analytics is the leading wastewater surveillance company in the U.S., tracking COVID-19 at hundreds of sewershed sites through its partnership with the CDC National Wastewater Surveillance System and independent Biobot Network. The dashboard has helpful national- and regional-level charts along with county-level data for sites in Biobot’s network.

Post-PHE update: Still active, no changes due to the PHE’s end. In fact, Biobot continues to add more wastewater testing sites to its network. - WastewaterSCAN: WastewaterSCAN is another leading wastewater project, led by professors at Stanford and Emory Universities. The project started with sites in California, but has since expanded nationwide; it’s tracking several other common viruses in addition to COVID-19.

Post-PHE update: Still active, similarly to Biobot’s dashboard. - For more wastewater data: Check out the COVID-19 Data Dispatch resource page with annotations on state and local dashboards.

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Since late 2020, the Kaiser Family Foundation has monitored American attitudes around COVID-19 vaccines and other pandemic issues. Updates were initially released monthly, but have become less frequent in the last year (the latest update was published on February 7, 2023).

Post-PHE update: This KFF project appears to be ongoing, but at a lower frequency of updates; the most recent update is still February 2023. A newer KFF dashboard (tracking Medicaid enrollment and unwinding) is also receiving ongoing updates. - Axios-Ipsos COVID-19 polls: Axios has partnered with the polling firm Ipsos on regular polls tracking COVID-19 views and behaviors. The polling data are available in PDF reports and in spreadsheets from Roper. In 2023, Axios and Ipsos shifted their focus from COVID-19 to broader questions about public health, with a new series of quarterly polls.

Post-PHE update: These two organizations will continue their new series of quarterly polls about public health, launched in early 2023. The most recent installment was posted this past week and includes questions about the PHE’s end, gun violence, opioids, and more.

Have I missed any major data sources? Send me an email or comment below to let me know, and I’ll highlight it in a future issue.

Editor’s note, April 2, 2023: This post has been updated with two additional dashboards (APM Research Lab and Walgreens), and additional information on the CDC’s wastewater surveillance dashboard.

Editor’s note, May 21, 2023: This post has been updated with notes about changes impacting these dashboards due to the end of the federal public health emergency (PHE).