How many people in the U.S. are currently hospitalized with COVID-19? As of yesterday, 83,200.

This question calls attention to the people deeply impacted by the pandemic—people in hospital beds, on ventilators, struggling to breathe. But it is also a deeply practical question. Public health experts and policymakers need to know where hospitals are becoming overwhelmed with patients in order to distribute supplies where they are most needed. Researchers and data nerds like myself, meanwhile, can use hospitalization metrics to track the pandemic’s impact on different communities: reported cases may be an unreliable metric, challenged by inadequate testing and uneven reporting guidelines, but it’s hard to miss a person in the hospital.

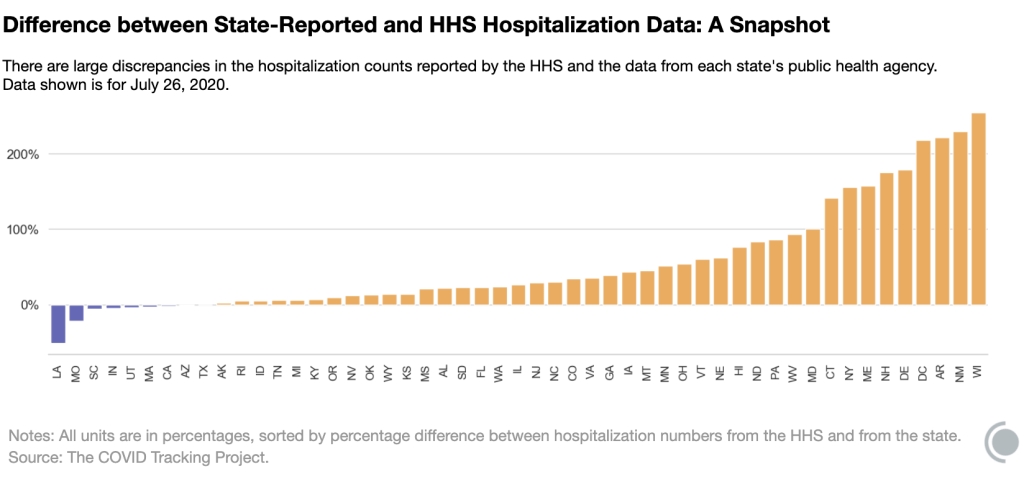

Longtime readers may remember that this newsletter started because of hospitalization data. Back in July, when hospitalization data moved from the purview of the CDC to the HHS, I wanted to explain why these data are so important and how the change in control impacted the numbers themselves. In the months since, the HHS has increased both the number of hospitals reporting to its system and the volume of information that is publicly released about those hospitals.

I’m returning to the topic now because the HHS has made two major upgrades to its hospitalization dataset in the past week: it now includes new admissions and staffing shortages for every state. The metrics are only available at the state level; I’m hoping that county- and even individual hospital-level numbers may be released in the coming weeks.

New admissions are a useful metric because they provide a clear picture of where outbreaks are worsening, and by what degree. Patients may stay in the hospital (and be counted in a “current hospitalizations” figure) for weeks on end; isolating the number of new patients incoming allows public health researchers to see how the burden on hospitals is growing.

Across the U.S., over 10,000 patients with confirmed cases of COVID-19 are now being admitted each day.

New COVID-19 admissions rose from about 6,000 per day in late October to over 10,000 per day in mid-November. Full-size chart available here.

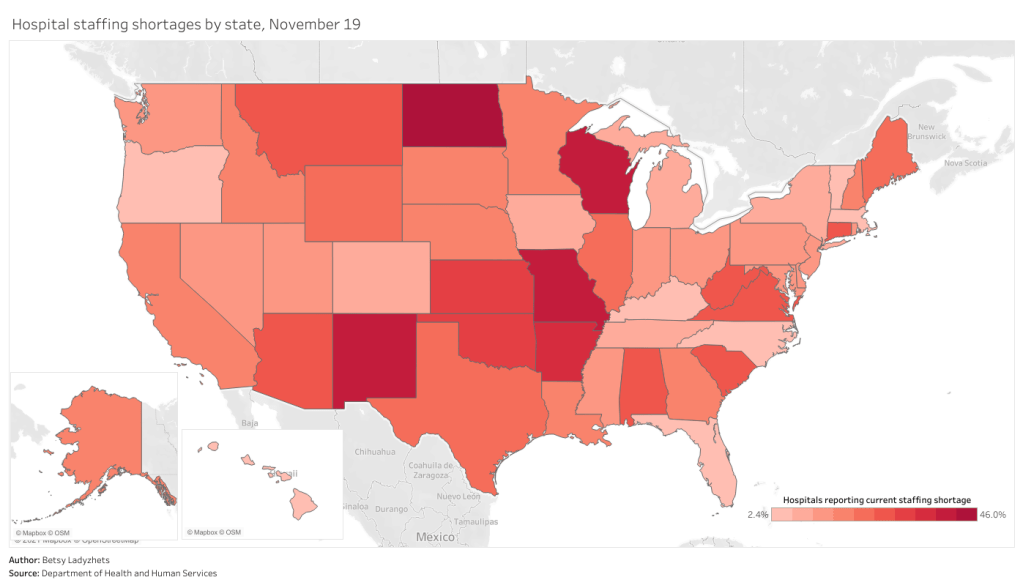

Staffing shortages, meanwhile, are a useful metric because they demonstrate where in the country healthcare systems are hardest hit. The HHS specifically asks hospitals to report when their staffing shortages are critical, meaning that these facilities are in serious danger of being unable to operate as normal. Staffing shortages may be the result of healthcare workers feeling burnt out, quitting, or becoming sick with COVID-19 themselves.

As of November 19, the most recent date these data are available, 18% of hospitals are currently facing a critical shortage—that’s about 1,100 out of the 6,100 hospitals reporting. 200 more hospitals report that they will be facing a critical shortage in the next week.

In North Dakota, Wisconsin, Missouri, and New Mexico, over one third of hospitals are facing a critical staffing shortage. Full-size chart available here.

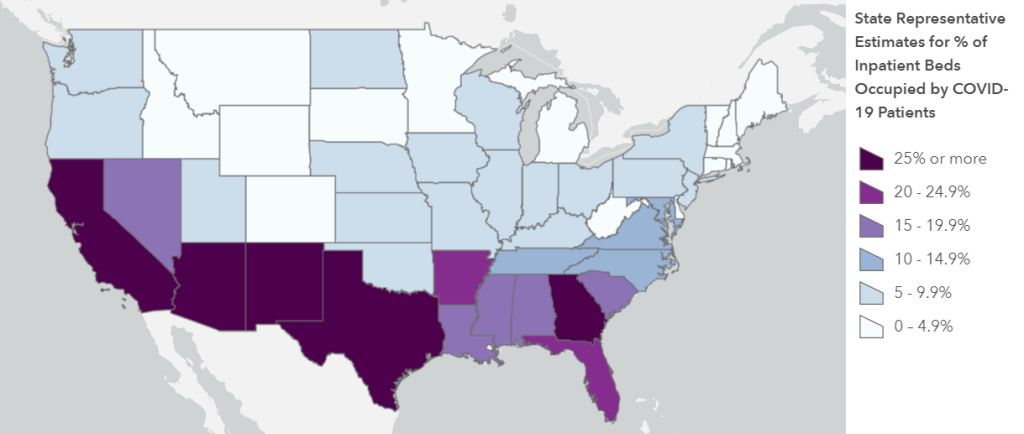

Finally, here’s a look at the nation’s current hospital capacity—that is, how many hospital beds are currently occupied with sick people. As of November 19, about 600,000 of the nation’s 980,000 hospital beds are full (61%). 88,000 of those people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 (9%). These numbers will grow in the coming weeks as thousands of recently diagnosed Americans become sicker.

Across the Midwest and South, several states have over three quarters of hospital beds occupied. Full-size chart available here.

For more context on these hospitalization data and what they mean for the exhausted, terrified healthcare workers serving patients, check out:

- Hospitals Can’t Go On Like This (The Atlantic)

- ‘People are going to die’: Hospitals in half the states are facing a massive staffing shortage as Covid-19 surges (STAT News)

- One Million Cases in Seven Days: This Week in COVID-19 Data, Nov 19 (COVID Tracking Project)

- Hospitals Know What’s Coming (The Atlantic)