COVID-19 is still a public health emergency. At the moment, this is true according to both the general definition of this term and official declarations by the federal government. But the latter could change in the coming months, likely leading to more fragmentation in U.S. COVID-19 data.

A reader recently asked me about the federal government’s ability to compile and report COVID-19 data, using our new anonymous Google form. They asked: “Will the CDC at some point stop reporting COVID data even though it may still be circulating, or is it a required, reportable disease?”

It’s difficult to predict what the CDC will do, as we’ve seen in the agency’s many twists and turns throughout the pandemic. That said, my best guess here is that the CDC will always provide COVID-19 data in some form; but the agency could be severely limited in data collection and reporting based on the disease’s federal status.

The CDC’s authority

One crucial thing to understand here is that the CDC does not actually have much power over state and local public health departments. It can issue guidance, request data, distribute funding, and so forth, but it isn’t able to require data collection in many circumstances.

Here’s Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at Harvard’s public health school and interim director of science at the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, explaining this dynamic. This quote is from an interview that I conducted back in May for my FiveThirtyEight story on the new center:

Outside of a public health emergency, CDC has no authority to require states to share data. And even in an emergency, for example, if you look on the COVID Data Tracker, there are systems that have half the states or some of the states. That’s because those were the ones that were willing to share. And that is a very big handicap of doing good modeling and good tracking… Everything you’re trying to measure, for any decision, is better if you measure it in all the states.

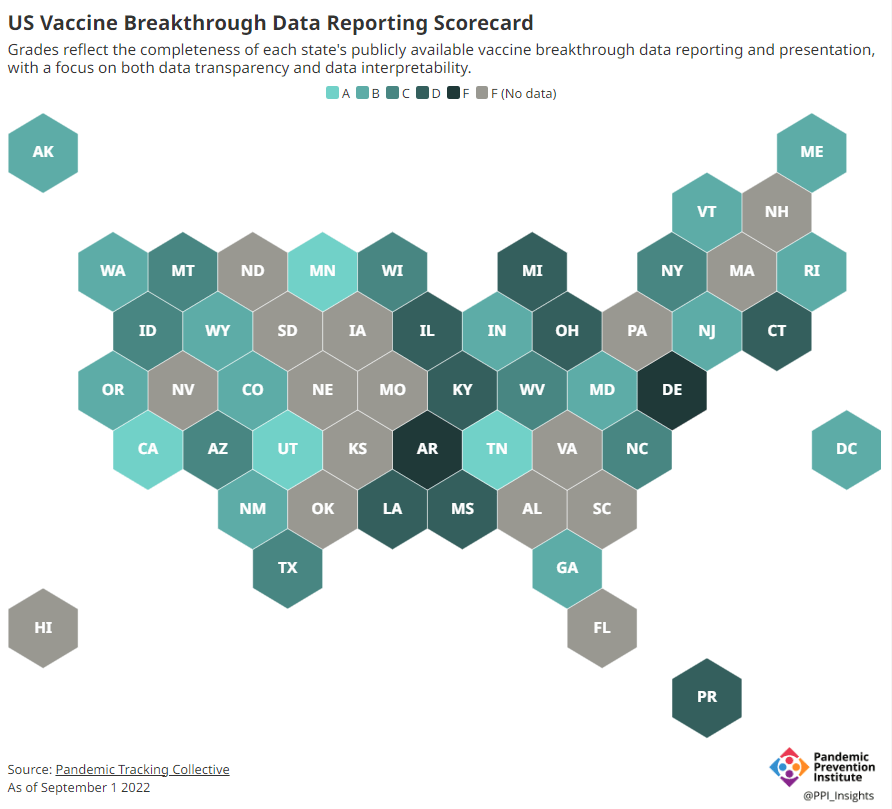

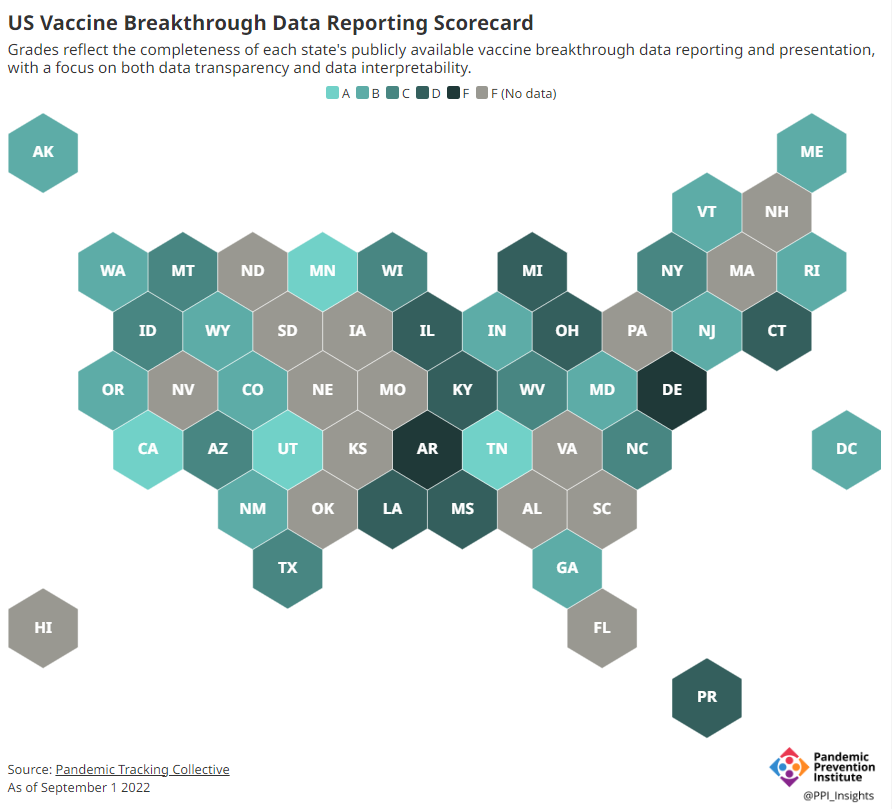

Consider breakthrough cases as one example. According to the Pandemic Prevention Institute’s scorecard for breakthrough data reporting, about half of U.S. states have D or F grades, meaning that they are reporting zero or very limited data on post-vaccination COVID-19 cases. The number of states with failing grades has increased in recent months, as states reduce their COVID-19 data resources. As a result, federal agencies have an incomplete picture of vaccine effectiveness.

Wastewater data is another example. While the CDC is able to compile data from all state and local public health departments with their own wastewater surveillance systems—and can pay Biobot to expand the surveillance network—the agency has no ability to actually require states to track COVID-19 through sewage. This lack of authority contributes to the CDC’s wastewater map still showing many empty spaces in states like Alabama and North Dakota.

The COVID-19 public health emergency

According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a federal public health emergency gives the HHS and CDC new funding for health measures and the authority to coordinate between states, among other expanded powers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal emergency was specifically used to require data collection from state health departments and individual hospitals, POLITICO reported in May. According to POLITICO, the required data includes sources that have become key to our country’s ability to track the pandemic, such as:

- PCR test results from state and local health departments;

- Hospital capacity information from individual healthcare facilities;

- COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals;

- COVID-19 cases, deaths, and vaccination status in nursing homes.

The federal COVID-19 public health emergency is formally controlled by HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra. Becerra most recently renewed the emergency in July, with an expiration date in October. Health experts anticipate that it will be renewed again in October, because HHS has promised to give states a 60-day warning before the emergency expires and there’s been no warning for this fall. That leaves us with a new potential expiration date in January 2023.

CDC officials are seeking to permanently expand the agency’s authority to include this data collection—with a particular priority on hospitalization data. But that hasn’t happened yet, to the best of my knowledge. So, what might happen to our data when the federal emergency ends?

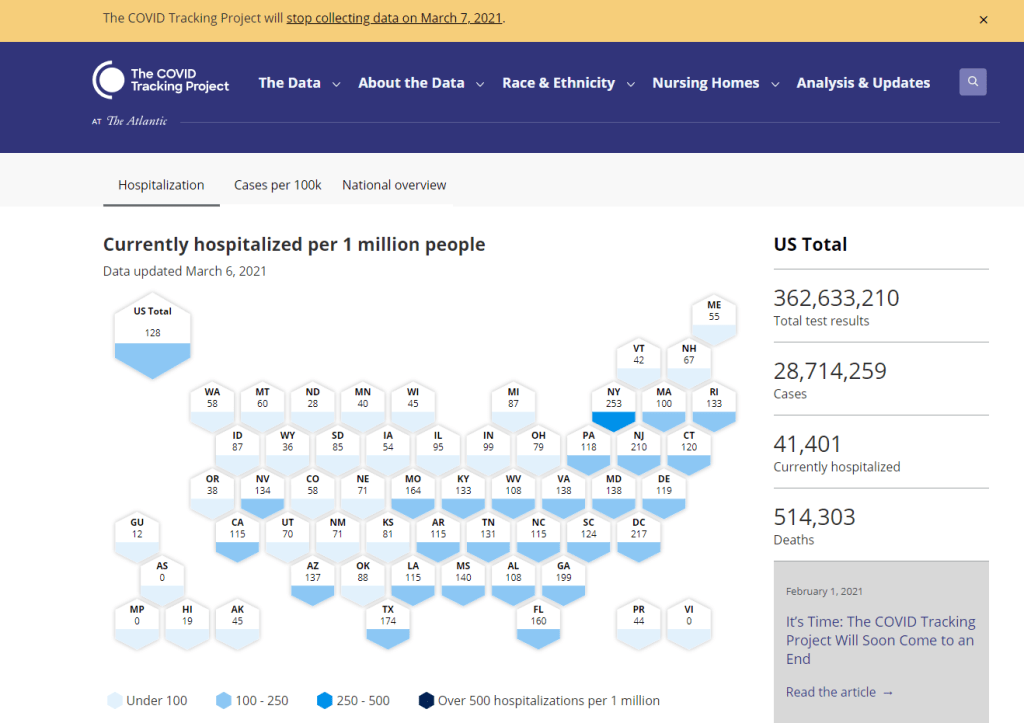

Most likely, metrics that the CDC currently requires from states will become voluntary. As we see right now with breakthrough cases and wastewater data, some states will probably continue reporting while others will not. Our federal data will become much more piecemeal, a patchwork of reporting for important sources such as hospitalizations and lab test results.

It’s important to note here that many states have already ended their own public health emergencies, following a trend that I covered back in February. Many of these states are now devoting fewer resources to free tests, contact tracing, case investigations, public data dashboards, and other data-related efforts than they were in prior phases of the pandemic. New York was the latest state to make such a declaration, with Governor Kathy Hochul letting her emergency powers expire last week.

How the flu gets tracked

COVID-minimizing officials and pundits love to compare “endemic” COVID-19 to the flu. This isn’t a great comparison for many reasons, but I do think it’s helpful to look at how flu is currently tracked in the U.S. in order to get a sense of how COVID-19 may be tracked in the future.

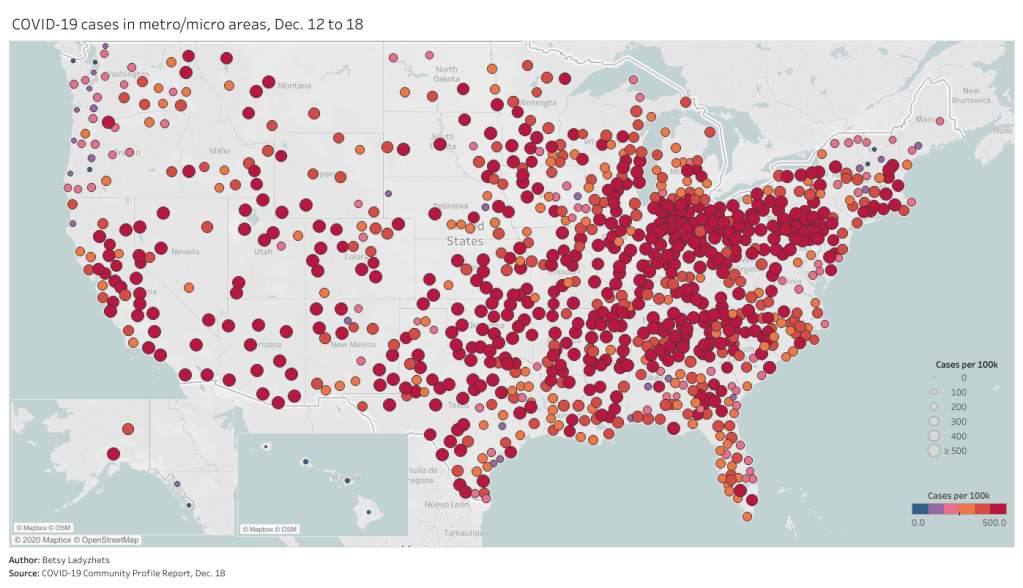

The U.S. does not count every flu case; that kind of precise tracking on a large scale was actually a new innovation for COVID-19. Instead, the CDC relies on surveillance networks that estimate national flu cases based on targeted tracking.

There are about 400 labs nationwide (including public health labs in all 50 states) participating in flu surveillance via the World Health Organization’s global program, processing flu tests and sequencing cases to track viral variants. Meanwhile, about 3,000 outpatient healthcare providers in the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network provide the CDC with flu-related electronic health records. You can read more about both surveillance programs here.

The CDC reports data from these surveillance programs on a dashboard called FluView. As you can see, the CDC provides estimates about flu activity by state and by different demographic groups, but the data may not be very granular (eg. no estimates by county or metro area) and are provided with significant time delays.

Other diseases are tracked similarly. For example, the CDC will track new outbreaks of foodborne illnesses like E. coli when they arise but does not attempt to log every infection. When researchers seek to understand the burden of different diseases, they often use hospital or insurance records rather than government data.

One metric that I’d expect to remain unchanged when the COVID-19 emergency ends is deaths: the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) comprehensively tracks all deaths through its death certificate system. But even provisional data from NCHS are reported with a delay of several weeks, with complete data unavailable for at least a year.

Epidemiologists I’ve interviewed say that we should be inspired by COVID-19 to improve surveillance for other diseases, rather than allowing COVID-19 to fall into the flu model. Wastewater data could help with this; a lot of wastewater researchers (including those at Biobot) are already working on tracking flu and other diseases. But to truly improve surveillance, we need more sustained investment in public health at all levels—and more data collection authority for the CDC and HHS.