This week, I had a big retrospective story published at FiveThirtyEight: I looked back at the major metrics that the U.S. has used to track COVID-19 over the past two years—and how our country’s fractured public health system hindered our use of each one.

The story is split into seven sections, which I will briefly summarize here:

- Case counts, January to March 2020: Early on in the pandemic, the U.S. had a very limited picture of COVID-19 cases due to our very limited testing: after rejecting a test made by the WHO, the CDC made its own test—which turned out to have contamination issues, further slowing down U.S. testing. In early March 2020, for example, the majority of cases in NYC were identified in hospitals, suggesting that official counts greatly underestimated the actual numbers of people infected.

- Tests administered, March to September 2020: Test availability improved after the first wave of cases, with organizations like the COVID Tracking Project keeping a close eye on the numbers. But there were a lot of challenges with the testing data (like different units across different states) and access issues for Americans with lower socioeconomic status.

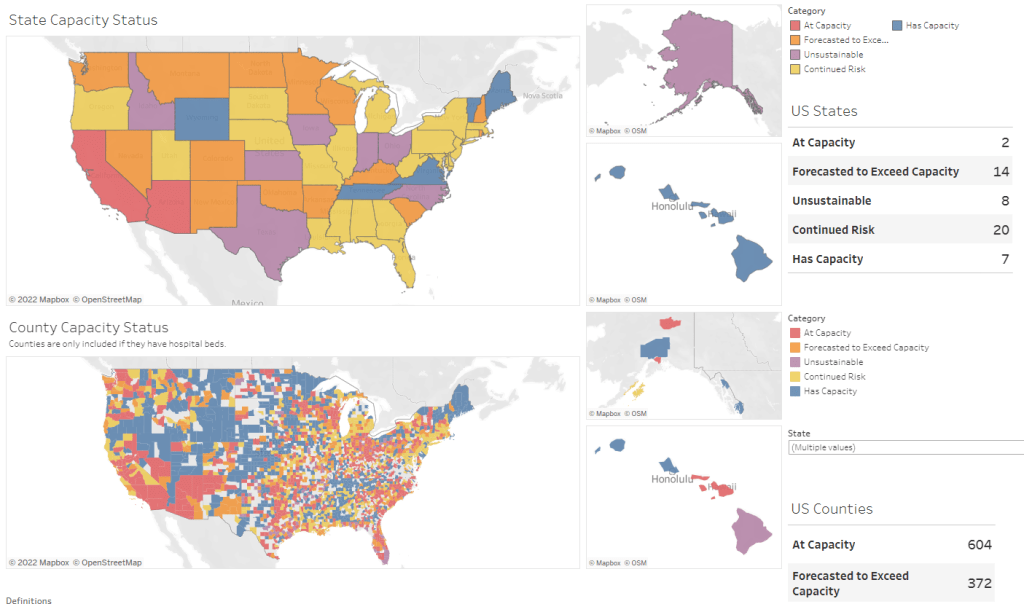

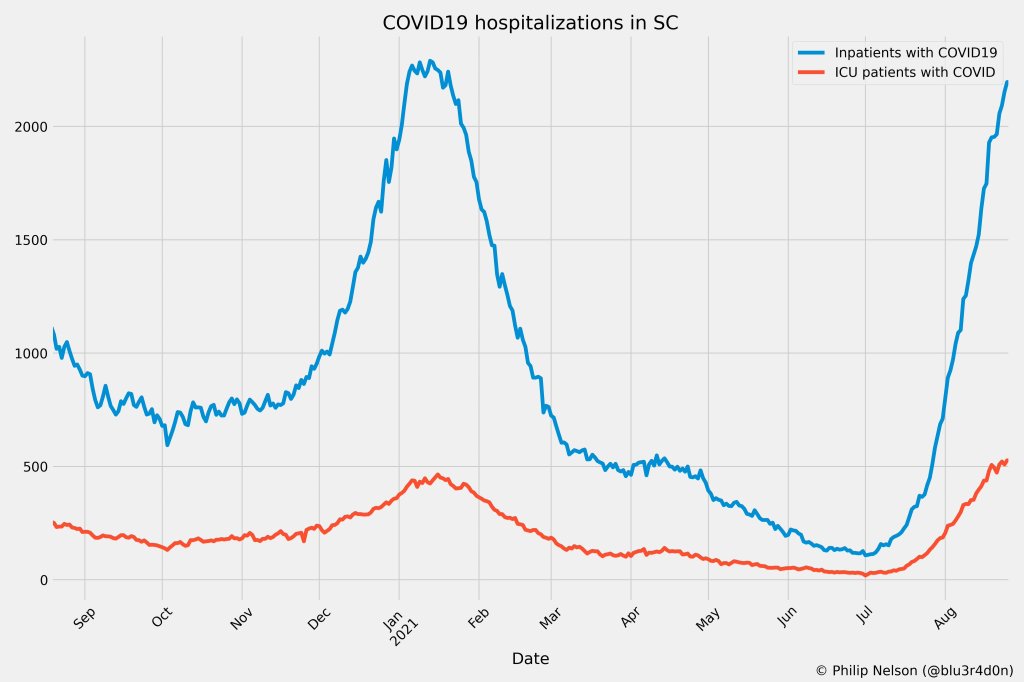

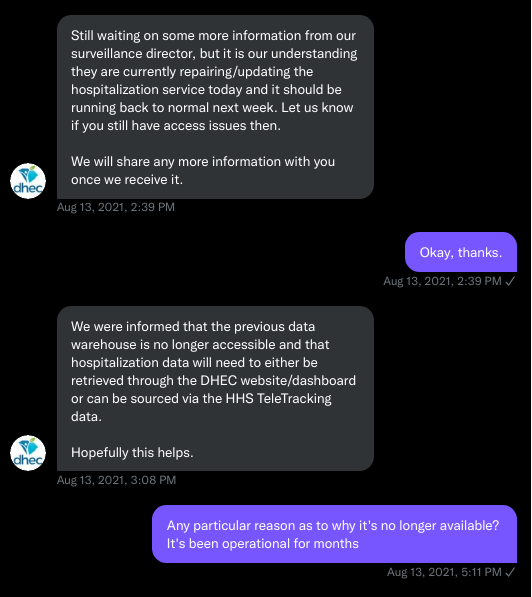

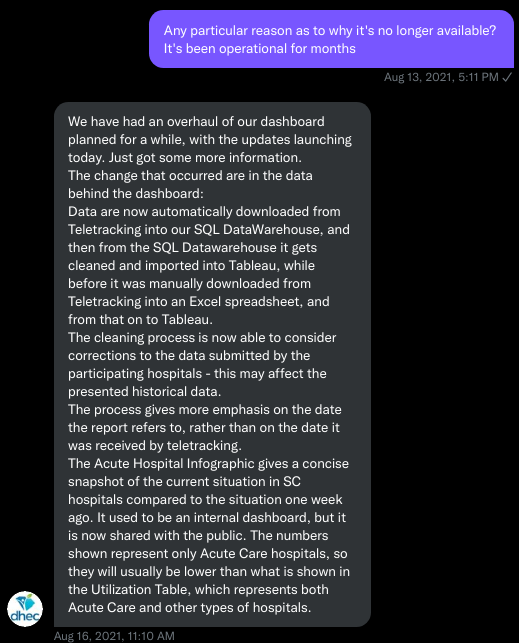

- Hospitalizations, October to December 2020: By late 2020, many researchers and journalists were considering hospitalizations to be a more reliable COVID-19 metric than cases. But it took a long time for hospitalization data to become reliable on a national scale, as the HHS launched a new tracking system in the summer and then took months to work out kinks in this system.

- Vaccinations, January to June 2021: When the vaccination campaign started in late 2020, it was “tempting to forget about all other COVID-19 metrics,” I wrote in the story. But the U.S.’s fractured system for tracking vaccinations made it difficult to analyze how close different parts of the country were to prospective “herd immunity,” and distracted from other public health interventions that we still needed even as people got vaccinated.

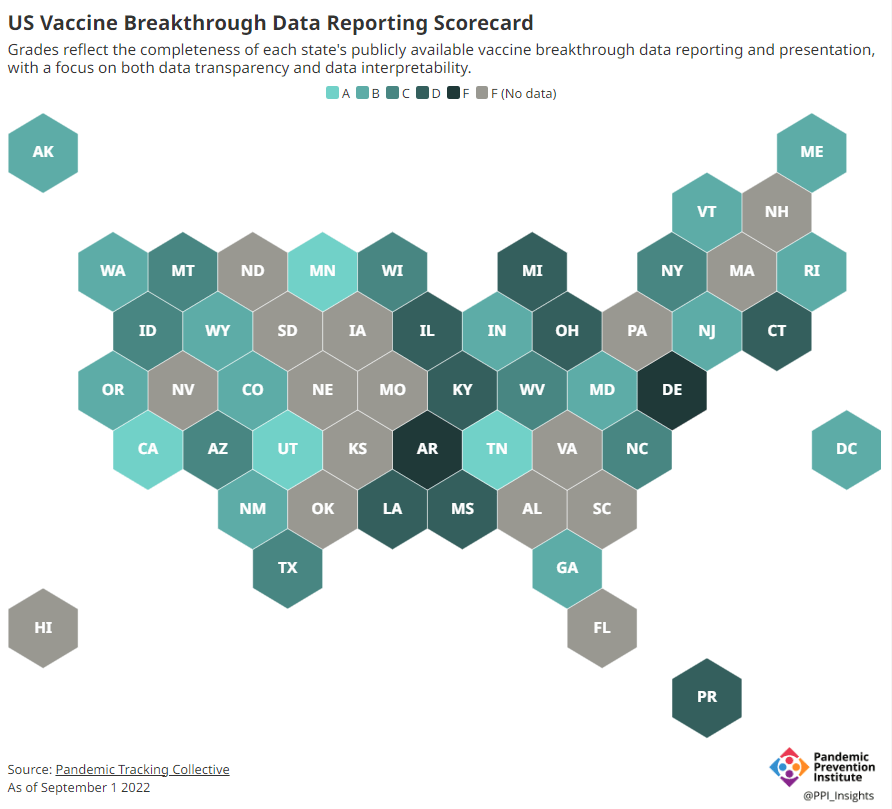

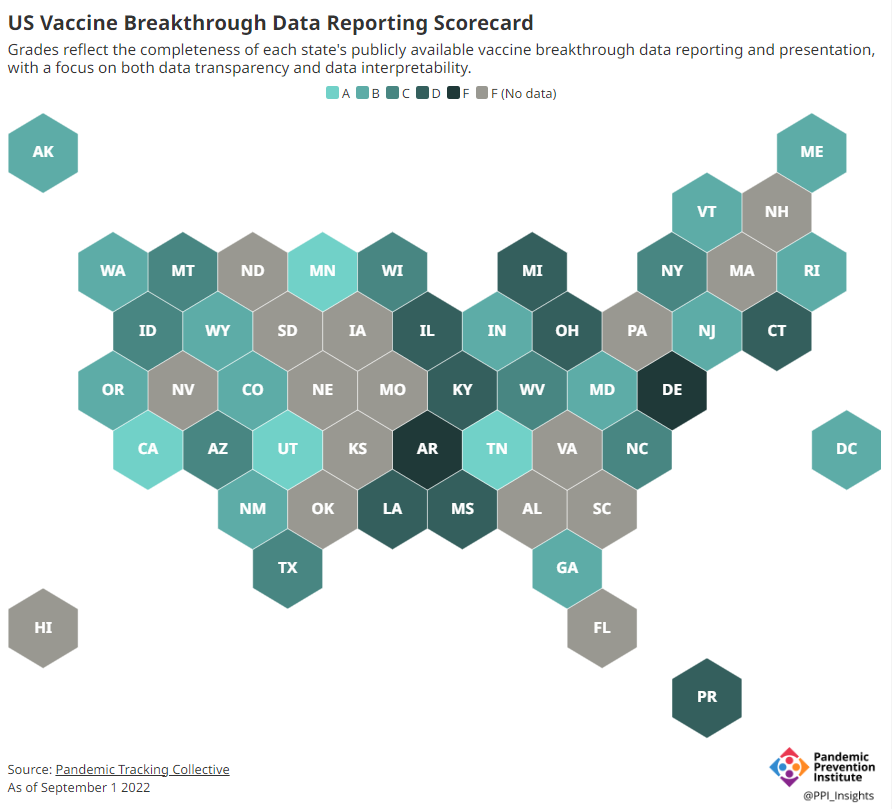

- Breakthrough cases, July to November 2021: The Delta surge caused widespread infections in people who had been vaccinated, but the CDC—along with many state public health agencies—was not properly equipped to track these breakthrough cases. This challenge contributed to a lack of good U.S. data on vaccine effectiveness, which in turn contributed to confusion around the need for booster shots.

- Hospitalizations (again), December to January 2022: The Omicron surge introduced a need for more nuance in hospitalization data, as many experts asked whether COVID-19 patients admitted with Omicron were actually hospitalized for their COVID-19 symptoms or for other reasons. Nuanced data can be useful in analyzing a variant’s severity; but all COVID-related hospitalizations cause strain on the healthcare system regardless of their cause.

- New kinds of data going forward: In our post-Omicron world, a lot of public health agencies are shifting their data strategies to treat COVID-19 more like the flu: less tracking of individual cases, and more reliance on hospitalization data, along with newer sources like wastewater. At this point in the pandemic, we should be fortifying data systems “for future preparedness,” I wrote, rather than letting the systems we built up during the pandemic fall to the wayside.

I did a lot of reporting for this piece, including interviews with some of the U.S.’s foremost COVID-19 data experts and communicators. As long as the piece is, there were a lot of metrics (and issues with these metrics) that came up in these interviews that I wasn’t able to include in the final story—so I wanted to share some bonus material from my reporting here.

Long COVID:

As I’ve discussed in previous issues, the U.S. has done a terrible job of collecting data on Long COVID. The NIH estimates that this condition follows a significant share of coronavirus infections (between 10% and 30%), but we have limited information on its true prevalence, risk factors, and strategies for recovery.

Here’s Dr. Eric Topol, the prolific COVID-19 commentator and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, discussing this data problem:

[Long COVID has] been given very low priority, very little awareness and recognition. And we have very little data to show for it, because it hasn’t been taken seriously. But it’s a very serious matter.

We should have, early on, gotten at least a registry of people —a large sample, hundreds of thousands of people prospectively assessed, like is being done elsewhere [in the U.K. and other countries]. So that we could learn from them: how long the symptoms lasted, what are the symptoms, what are the triggers, what can be done to avoid it, the role of vaccines, the role of boosters, all this stuff. But we have nothing like that.

The NIH’s RECOVER initiative may answer some of these questions, but it will take months—if not years—for the U.S. to actually collect the comprehensive data on Long COVID that we should have started gathering when the condition first began gaining attention in 2020.

Demographic data:

In the testing section of the story, I mention that the U.S. doesn’t provide much demographic data describing who’s getting tested for COVID-19. There is actually a little-known provision in the CARES Act that requires COVID-19 testing providers to collect certain demographic data from all people who seek tests. But the provision is not enforced, and any data that are collected on this subject aren’t making it to most state COVID-19 dashboards, much less to the CDC’s public data dashboard.

Here’s Dr. Ellie Murray, an epidemiologist at the Boston University School of Public Health, discussing why this is an issue:

We don’t collect reason for seeking a test. We don’t collect age, race, ethnicity, occupation of people who seek a test. Those kinds of things could provide us with some really valuable information about who is getting tested, when, and why—that could help us figure out, what are the essential occupations where people are having a lot of exposures and therefore needing to get a lot of tests? Or are there occupations where we’re seeing a lot of people end up in hospital, who have those occupations, but they’re not getting tests, because actually, the test sites are nowhere near where they need to work, or they don’t have the time to get there before they close.

And so we don’t really know who is getting tested, and that, I think, is a bigger problem, than whether the numbers that are being tested tell us anything about the trajectory of COVID. Because we have case data, and hospitalization data, and death data to tell us about the trajectory. And the testing could really tell us more about exposure, and concern, and access—if we collected some more of this data around who is getting tested and why.

Test positivity:

Speaking of testing: another metric that I didn’t get into much in the story was test positivity. Test positivity—or, the share of COVID-19 tests that return a positive result—has been used from the CDC to local school districts as a key metric to determine safety levels. (For more on this metric, check out my FAQ post from this past January.)

But even when it’s calculated correctly, test positivity faces the same challenges as case data: namely, bias in who’s getting tested. Here’s Lauren Ancel Meyers, director of the University of Texas at Austin’s COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, explaining this:

Test positivity is just as fraught [as cases]. It’s just as difficult, because you need to know the numerator and the denominator—what’s influencing the numerator and the denominator? Who is going to get tested, who has access to tests? … It used to be, at the very beginning [of the pandemic], nobody could get a test who wanted a test. And now, today, everybody has a test in their medicine cabinet, and they don’t get reported when they test. It’s different issues that have ebbed and flowed throughout this period.

Often, if you’re a good data analyst or a modeler, and you have all the information, you can handle those kinds of biases. But the problem is, we don’t know the biases from day to day. And so even though there are statistical tools to deal with incomplete bias, without knowing what those biases are, it’s very hard to do reliable inference, and really hard to understand what’s actually going on.

Genetic surveillance:

Also related to testing: genetic surveillance for coronavirus variants of concern. Genetic surveillance is important because it can help identify new variants that may be more transmissible or more likely to evade protection from vaccines. It can additionally help track the qualities of concerning variants once they are identified (if variant data is linked to hospitalization data, vaccination data, and other metrics—which is not really happening in the U.S. right now.)

Our current genetic surveillance systems have a lot of gaps. Here’s Leo Wolansky, from the Rockefeller Foundation’s Pandemic Prevention Institute (PPI), discussing how his organization seeks to address these challenges:

[We’re trying to understand] where our blind spots are, and the bias that we might experience with a lot of health system reporting. One of the things that PPI has been doing is identifying centers of excellence in different parts of the world that can improve the sequencing of new cases in underrepresented countries. And so for example, we’ve provided quite a bit of support to the folks in South Africa that ultimately rang the alarm on Omicron.

We’re also doing this by actually trying to systematically assess countries’ capacity for this type of genomic surveillance. So thinking about, how many tests have been recorded? What’s that test positivity rate? Do we have confidence in the basic surveillance system of the country? And then, do we also see enough sequences, as well as sequencing facility data, to demonstrate that this country can sequence and just isn’t doing enough—or cannot sequence because it needs foundational investment in things like laboratories and devices. We’ve been mapping this capacity just to make sure that we understand where we should be investing as a global community.

The Pandemic Prevention Institute is taking a global perspective in thinking about data gaps. But these gaps also exist within the U.S., as is clear when one looks at the differences in published coronavirus sequences from state to state. Some states, like Wyoming, Vermont, and Colorado, have sequenced more than 10% of their cumulative cases, according to the CDC. Others, like Oklahoma, Iowa, and South Dakota, have sequenced fewer than 3%. These states need additional investment in order to thoroughly monitor coronavirus transmission among their residents.

Cohort studies:

In a cohort study, researchers follow a group of patients over time in order to collect long-term data on specific health conditions and/or the outside factors that influence them. The U.S. has set up a few cohort studies for COVID-19, but they haven’t been designed or utilized in a way that has actually provided much useful data—unlike cohort studies in some other countries. (The U.K., for example, has several ongoing cohort studies collecting information on COVID-19 symptoms, infections in schools, seroprevalence, and more.)

Here’s Dr. Ellie Murray explaining the lost potential of these studies in the U.S.:

There are a number of existing cohort studies that have been asked or who asked to pivot to collecting COVID information and therefore collecting long-term COVID information on their cohorts. But there doesn’t seem to be any kind of system to [determine], what are the questions we need answered about COVID from these kinds of studies? And how do we link up people who can answer those questions with the data that we’re collecting here, and making sure we’re collecting the right data? And if this study is going to answer these questions, and this one is going to answer those questions—or, here’s how we standardize those two cohorts so that we can pull them together into one big COVID cohort.

And so, we end up in this situation where, we don’t know what percent of people get Long COVID, even though we’ve been doing this for over two years. We don’t even really know, what are all the different symptoms that you can get from COVID? … There are all these questions that we could be sort-of systematically working our way through, getting answers and using them to inform our planning and our response. [In addition to having] standardized questions, you also need a centralized question, instead of just whatever question occurs to someone who happens to have the funding to do it.

Excess deaths:

Excess deaths measure the deaths that occur in a certain region, over a certain period of time, above the number of deaths that researchers expect to see in that region and time period based on modeling from past years’ data. Excess deaths are the COVID-19 metric with the longest lag time: it takes weeks from initial infection for someone to die of the disease, and can take weeks further for a death certificate to be incorporated into the public health system.

Once that death information is available, however, it can be used to show the true toll of the pandemic—analyzing not just direct COVID-19 deaths, but also those related to isolation, financial burden, and other indirect issues—as well as who has been hit the hardest.

Here’s Cecile Viboud, a staff scientist at the NIH who studies infectious disease mortality, discussing this metric:

We’ve been using the excess death approach for a long time. It comes from flu research, basically starting in 1875 in the U.K. And it was used quite a lot during the 1918 pandemic. It can be especially good in examining historical records where you don’t have lab confirmation—there was no testing ability back in those days…

So, I think it’s kind of natural to use it for a pandemic like COVID-19. Very early on, you could see how useful this method was, because there was so little testing done. In March and April 2020, you see substantial excess, even when you don’t see lab-confirmed deaths. There’s a disconnect there between the official stats, and then the excess mortality… [We can also study] the direct effect of COVID-19 versus the indirect effect of the pandemic, like how much interventions affected suicide, opioids, death, accidents, etc. The excess approach is also a good method to look at that.

Viboud also noted that excess deaths can be useful to compare different parts of the U.S. based on their COVID-19 safety measures. For example, one can analyze excess deaths in counties with low vaccination rates compared to those with high vaccination rates. This approach can identify the pandemic’s impact even when official death counts are low—an issue that the Documenting COVID-19 project has covered in-depth.

Again, you can read the full FiveThirtyEight story here!

More federal data