- Free at-home tests from the federal government: The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Postal Service are restarting their program offering free COVID-19 rapid, at-home tests. Starting tomorrow, every U.S. household will be able to order four more tests at covidtests.gov. HHS also announced that it’s buying about 200 million further rapid tests from major manufacturers, paying a total of $600 million to twelve companies. Of course, four tests per household is pretty minimal when you consider all the exposures people are likely to have this fall and winter—but it’s still helpful to see the federal government acknowledge a continued need for testing.

- New grants support Long COVID clinics: The HHS and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also announced a new grant program for clinics focused on Long COVID, aiming to make care for this condition more broadly accessible to underserved communities. Nine clinics across the country have received $1 million each, with the opportunity to renew their grants over the next five years. (At least, that’s my interpretation of the HHS press release, which says $45 million in total is allocated to this program.) This is a pretty significant announcement, as it marks the first time that the federal government is specifically funding Long COVID care; funding has previously gone to RECOVER and other research projects.

- CDC announces new disease modeling network: One more federal announcement: the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics has established a new program to improve the country’s disease surveillance, working with research institutions across the country. The CDC has awarded $262.5 million of funding to the thirteen institutions participating in this program, which it’s calling the Outbreak Analytics and Disease Modeling Network. These institutions will develop new surveillance tools, test them in small-scale projects, and scale up the successful options to broader public health systems. For more context on the CDC’s forecasting center, see my story for FiveThirtyEight last year.

- Testing wildlife for COVID-19: Speaking of surveillance: researchers at universities and public agencies are collaborating on new projects aiming to better understand how COVID-19 is spreading and evolving among wild animals. One project, at Purdue University, is focused on developing a test to better detect SARS-CoV-2 among wild animals. A second project, at Penn State University, is focused on increased monitoring, with plans to test 58 different wildlife species and identify sources of transmission from animals to humans. Both projects received grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and involve collaboration with state environmental agencies.

- Paxlovid access falls along socioeconomic lines: A new study, published this week in JAMA Network Open, examines disparities in getting Paxlovid. Researchers at the National Institutes of Health analyzed public data on Paxlovid availability as of May 2023. Counties with higher poverty, less health insurance coverage, and other markers of high socioeconomic vulnerability had significantly less access to Paxlovid than better-off counties, the scientists found. Meanwhile, a separate study (also in JAMA Network Open last week) found that Paxlovid and another antiviral treatment, made by Merck, both remain very effective in reducing severe COVID-19 symptoms. Improving access to these treatments should be a top priority for the public health system.

- Undercounted COVID-19 cases in Africa: One more study that caught my attention this week: researchers at York University in Canada developed a mathematical model to assess how many people actually got COVID-19 in 54 African countries during the first months of the pandemic. Overall, only 5% of cases in these countries were actually reported, the researchers found, with a range of reporting from 30% in Libya to under 1% in São Tomé and Príncipe. A majority of cases in these countries were asymptomatic, the models suggested, indicating many people may not have realized they were infected. The study shows “a clear need for improved reporting and surveillance systems” in African countries, the authors wrote.

Tag: HHS

-

Sources and updates, September 24

-

The NIH has little to show for $1 billion allocated to Long COVID research

Article header from STAT News; illustration by Mike Reddy. In December 2020, Congress gave the National Institutes of Health $1.2 billion to study Long COVID. That money was used to fund the RECOVER initiative, billed as a thorough study of this condition and an effort to help patients actually recover from the often-debilitating long-term effects of COVID-19.

But it’s been more than two years, and the RECOVER initiative doesn’t have much to show for that money—besides a growing number of frustrated people in the Long COVID community. Clinical trials haven’t started yet, very limited research findings have been published, and some long-haulers involved with the initiative are losing faith in its ability to find answers.

I collaborated with Rachel Cohrs, a reporter at STAT News, on a thorough investigation into RECOVER’s problems. We combed through documents and data, talked to a number of people involved with the initiative, and researched the broader context around RECOVER.

This project was a collaboration between STAT and MuckRock, and you can read the full story on STAT’s website or on MuckRock’s. I also wrote a Twitter thread with some highlights:

As I wrote on Twitter, I want to keep reporting on RECOVER, as I know there are other problems with the initiative that weren’t captured in this story. If anyone reading this has additional information to share, please shoot me an email or reach out on social media. (You can also reach out to ask for my number on Signal, a secure messaging platform.)

Here’s the story’s introduction, to give you an idea of what we found:

The federal government has burned through more than $1 billion to study long Covid, an effort to help the millions of Americans who experience brain fog, fatigue, and other symptoms after recovering from a coronavirus infection.

There’s basically nothing to show for it.

The National Institutes of Health hasn’t signed up a single patient to test any potential treatments — despite a clear mandate from Congress to study them. And the few trials it is planning have already drawn a firestorm of criticism, especially one intervention that experts and advocates say may actually make some patients’ long Covid symptoms worse.

Instead, the NIH spent the majority of its money on broader, observational research that won’t directly bring relief to patients. But it still hasn’t published any findings from the patients who joined that study, almost two years after it started.

There’s no sense of urgency to do more or to speed things up, either. The agency isn’t asking Congress for any more funding for long Covid research, and STAT and MuckRock obtained documents showing the NIH refuses to use its own money to change course.

“So far, I don’t think we’ve gotten anything for a billion dollars,” said Ezekiel Emanuel, a physician, vice provost for global initiatives, and co-director of the Healthcare Transformation Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. “That is just unacceptable, and it’s a serious dysfunction.”

Eric Topol, the founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, said he expected the NIH would have launched many large-scale trials by now, and that testing treatments should have been an urgent priority when Congress first gave the agency money in late 2020.

“I don’t know that they’ve contributed anything except more confusion,” Topol said.

Patients and researchers have already raised alarms about the glacial pace of the NIH’s early long Covid efforts. But a new investigation from STAT and the nonprofit news organization MuckRock, based on interviews with nearly two dozen government officials, experts, patients, and advocates, and internal NIH correspondence, letters, and public documents, underscores that the NIH hasn’t picked up the pace — instead, the delays have compounded.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why progress is so stalled, experts and patients involved in the project emphasized, because the NIH has obscured both who is in charge of the long Covid efforts and how it spent the money. The broader Biden administration has also missed opportunities for oversight and accountability of the effort — despite the president’s lofty promises to focus on the disease.

The NIH’s blunders have massive ramifications for the more than 16 million Americans suffering from long Covid, in addition to those with other, similar chronic diseases. As the biggest government-funded study on this topic, the NIH initiative, dubbed RECOVER, sets precedents for future research and clinical guidelines. It will dictate how doctors across the country treat their patients — and, in turn, impact people’s ability to access work accommodations, disability benefits, and more.

“The NIH RECOVER study is pointless,” said Jenn Cole, a long Covid patient based in Brooklyn, N.Y., who wanted to enroll in the study but found the process inaccessible. The research is “a waste of time and resources,” she said, and fails to use patients’ tax dollars for their benefit.

In response to STAT and MuckRock’s questions, the NIH and an institute at Duke University managing the clinical trials defended the initiative, without providing a clear explanation for the delays.

The NIH said it chose to fund a large-scale research program instead of small-scale studies to make sure data and processes could be shared across different groups of patients, adding that clinical trials will be launching soon. In these trials, standardized study designs will allow the agency to test multiple treatments across multiple sites. If there are signals a drug works, the agency said it can pivot to devote more resources there.

A Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson said the agency has made progress over the last year in responding to long Covid, and that there are research efforts underway in addition to the RECOVER program.

“The Administration remains committed to addressing the longer-term impacts of the worst public health crisis in a century,” HHS said.

Read the full story on STAT’s website or on MuckRock’s.

More Long COVID reporting

-

Sources and updates, April 9

- Second Omicron boosters for high-risk adults: The FDA and CDC are planning to authorize a second round of bivalent, Omicron-specific vaccines for high-risk adults, the Washington Post reported this week. This decision will apply to Americans over age 65 and those who have compromised immune systems, with these groups becoming eligible four months after their initial bivalent boosters. It’s unclear exactly when the decision will become official; the FDA and CDC will make authorizations sometime “in the next few weeks,” according to WaPo.

- HHS announces (underwhelming) Long COVID progress: This week marks one year since Biden issued a presidential memo kicking off a “whole-of-government response” to Long COVID. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) commemorated the occasion with a fact sheet sharing the federal government’s progress so far. Unfortunately, that progress has been fairly minor, mostly consisting of reports and guidance that largely summarize existing government programs or build on existing systems (such as Veterans Affairs hospitals). Many of the Long COVID programs that Biden previously proposed have not received funding from Congress; meanwhile, the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER initiative, the one program that has been funded, has faced a lot of criticism.

- RECOVER PIs recommend action on treatment: Speaking of RECOVER: this week, a group of scientists leading research hubs within the national study called for federal funding that would support treatment. The principal investigators (PIs) of these hubs have developed expertise in Long COVID through recruiting and studying patients, leading them to identify gaps in available medical care for long-haulers. To respond, the PIs recommend that Congress allocate $37.5 million to support Long COVID medical care at the RECOVER research sites. Their proposed budget includes patient outreach, telehealth support, educating healthcare workers on Long COVID, and more.

- Ventilation improvements in K-12 schools: The CDC released a new study this week in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, sharing results of a survey (conducted last fall) including about 8,400 school districts representing 62% of public school students in the U.S. Research company MCH Strategic Data asked the districts about how they’d improved ventilation in their school buildings, along with other COVID-19 safety measures. About half of the districts reported “maintaining continuous airflow in classrooms,” one-third reported HVAC improvements, 28% reported using HEPA filters, and 8% reported using UV disinfectants. The results indicate that many districts have a long way to go in upgrading their indoor air quality.

- Flu vs. COVID-19 mortality risk: Ziyad Al-Aly and his colleagues at the VA healthcare system in St. Louis have published another paper analyzing COVID-19 through the VA’s electronic health records. This study, published in JAMA Network, describes the mortality risk of COVID-19 compared to seasonal flu for patients hospitalized during the 2022-2023 winter season. The researchers evaluated about 9,000 COVID-19 patients and 2,400 flu patients, finding that risk of death for COVID-19 patients in the 30 days following hospitalization was about 1.6 times as high as the risk of death for flu patients. Despite great advances in vaccines and treatments, COVID-19 remains more dangerous than other seasonal viruses, the study suggests.

- Biobot launches mpox dashboard: This week, leading wastewater surveillance company Biobot Analytics launched a new dashboard displaying its mpox (formerly monkeypox) monitoring. Biobot tests for mpox at hundreds of sewage sites across the U.S., largely through its partnership with the CDC, and will continue this monitoring through at least summer 2023. The new dashboard shows mpox detections nationally over time and monitoring sites by state; it also includes some information on how mpox surveillance differs from COVID-19 surveillance.

-

Sources and updates, February 19

Just a couple of updates today!

- Test positivity will become less reliable after PHE ends: CBS News COVID-19 reporter Alexander Tin flagged last week that, after the federal public health emergency for COVID-19 ends this spring, private labs that process PCR tests will no longer be required to report their results to state health departments. States will still report any results they get to the CDC, but federal officials expect that this data will become much less reliable, according to a background press briefing from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Case data are already unreliable; soon, we won’t even have consistent test positivity data to tell us how unreliable they are. This may be one of several data sources that get worse after the end of the PHE.

- HHS is supporting improved healthcare data sharing: The inability to connect different health records systems (or lack of interoperability, to use the technical term) has been a big problem during the pandemic, as researchers and health officials often couldn’t answer questions that require multiple health datasets. HHS has taken some steps to improve this situation, while also making it easier for individual patients to access their personal records. Most recently, HHS announced that it’s chosen six companies and organizations to develop data-sharing platforms, according to POLITICO. It’ll take some time for these organizations to start actually sharing data, but I’m glad to see any movement on this important issue.

- Yes, vaccination is still the best way to get protected from COVID-19: A new study from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, published in the Lancet this week, has been making the rounds on social media recently. Anti-vax pundits are claiming the study shows that immunity from a prior coronavirus infection is more effective than immunity from vaccination at preventing future severe COVID-19. While the study does show that a prior infection can be helpful, the authors found a significant drop in the value of this type of protection after Omicron variants started circulating in late 2021. And, as some commentators have pointed out, infections can always lead to severe symptoms and Long COVID—the risks from vaccination are much lower. Basically, this XKCD comic remains accurate.

-

What the public health emergency’s end means for COVID-19 data

This past Monday, the White House announced that the federal public health emergency for COVID-19 will end in May. While this decision might be an accurate reflection of how most of the U.S. is treating COVID-19 right now, it has massive implications for Americans’ access to tests, treatments, vaccines—and data.

I wrote about the potential data issues last September, in anticipation of this emergency ending. Here are the highlights from that post:

- Outside of a public health emergency, the CDC has limited authority to collect data from state and local health agencies. And even during the emergency, the CDC’s authority has been minimal enough that national datasets for some key COVID-19 metrics (like breakthrough cases and wastewater surveillance) have been very spotty.

- When the federal emergency ends, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) may lose its ability to require reporting of some key data, including: PCR test results (from states), hospital capacity information and COVID-19 patient numbers (from individual hospitals), COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes.

- It’s possible that the HHS and/or CDC will negotiate new data reporting requirements with states and other entities that don’t rely on the public health emergency. They have about three months to do this. I haven’t seen much news on that yet, but I’ll keep an eye out and share updates as I find them.

- Regardless, I expect that reporting COVID-19 numbers to federal data systems will become even more voluntary than it already is for health agencies, hospitals, congregate facilities, and other settings. We will likely have to rely more on targeted surveillance systems (which compile data from a subset of healthcare facilities) rather than comprehensive national datasets, similar to our current surveillance systems for the flu and other endemic diseases.

At the same time, the public health emergency’s end will lead to changes in the distribution of vaccines, tests, and treatments. The Kaiser Family Foundation has a helpful explanation of exactly what’s changing. Here are the highlights:

- Vaccines will remain free to all as long as the stockpile of doses purchased by the federal government lasts. However, the ending emergency will likely impact the government’s ability to buy more vaccines—including future boosters that might be targeted to new variants. Vaccine manufacturers are planning to raise their prices, and cost will become a burden for uninsured and underinsured people.

- At-home, rapid tests will no longer be covered by traditional Medicare, while Medicare Advantage coverage will vary by plan. Most private insurance providers will likely still cover the tests, but prices may go up (similarly to the prices for vaccines).

- PCR tests are also likely no longer going to be covered by a lot of insurance plans and/or are going to get more expensive. Notably, Medicaid will continue covering both at-home and PCR tests through September 2024.

- Treatments (primarily Paxlovid right now) will remain free for doses purchased by the federal government, similar to the situation with vaccines. After the federally-purchased supply runs out, however, we will similarly see rising costs and dwindling access.

KFF also has produced a detailed report about how the end of the federal emergency will impact healthcare coverage more broadly.

In short, the end of the public health emergency will make it harder for Americans to get tested, receive treatments, and stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines. The testing access changes, in particular, will lead to official case numbers becoming even less accurate, as fewer people seek out tests. At the same time, Americans will lose access to the data we need to know how much of a threat COVID-19 presents in the first place.

It’s also worth noting that, on the same day the White House announced the end of its emergency declaration, the World Health Organization announced the opposite: the global public health emergency is continuing, though it may end later in 2023. As Americans largely ignore COVID-19, millions of people around the world are unvaccinated, facing new surges, dealing with new variants, etc.

COVID-19 clearly remains a looming threat at the global level. In the U.S., we technically have the best vaccines and treatments to deal with the disease—but these tools are going underutilized, and the Biden administration’s decision this week will only make it harder for people to get them. Maybe we shouldn’t have to rely on an emergency declaration to get basic data and access to health measures in the first place.

More federal data

-

Orders of free at-home COVID-19 tests varied widely by state

On September 2, 2022, the federal government stopped taking orders for free at-home COVID-19 tests. The distribution program, which launched during the first Omicron surge in early 2022, allowed households to order free tests up to three times, with either four or eight tests in each order.

The day this program ended, I sent a public records request to the federal government asking for data on how many tests were distributed. I filed it through MuckRock’s portal, so both the original request and my correspondence with the U.S. Postal Service’s records office are publicly available.

Last week, the USPS fulfilled my request. While I’d requested data by state, county, and/or ZIP code, the agency only sent over at-home test orders and distribution numbers by state. According to the formal response letter they sent, more granular data would (somehow) count as “commercial information” and is therefore exempt from FOIA.

Now, obviously, I think that far more data on the test distribution program should be publicly available. As I wrote back in January when the program started, in order to truly evaluate the success of this program, we need test distribution numbers by more specific geographies and demographic groups.

Still, the state-by-state data are better than nothing. With these data, we can see that states with the highest volume of at-home test orders fall on the East and West coasts, with people living in the South and Midwest less likely to use the program.

(The population data that I used to calculate these per capita rates are from the HHS Community Profile Report.)

With the data from my FOIA request, we can see that states with higher vaccination rates also had more people taking advantage of the free COVID-19 test program. States like Vermont and Hawaii rank high up for both metrics, while states like North Dakota and Wyoming are on the lower end for both.

At the same time, many of the states where fewer people ordered the free tests are also states that saw higher COVID-19 death rates in 2022. In Mississippi, for example, about 433 people died of COVID-19 for every 100,000 residents since the year started—the highest death rate of any state. But people in the state ordered free tests at a rate under 0.3 per capita.

These charts basically confirm what many public health experts suspected about the free COVID-19 test program: Americans who already were more protected against COVID-19 (thanks to vaccination) were most likely to order tests. Just as we’re seeing now with the Omicron-specific booster shots, a valuable public health measure went under-utilized here.

I invite other journalists to report on these data; if you do, please link back to my original FOIA request on MuckRock!

More testing data

-

Potential data fragmentation when the federal COVID-19 public health emergency ends

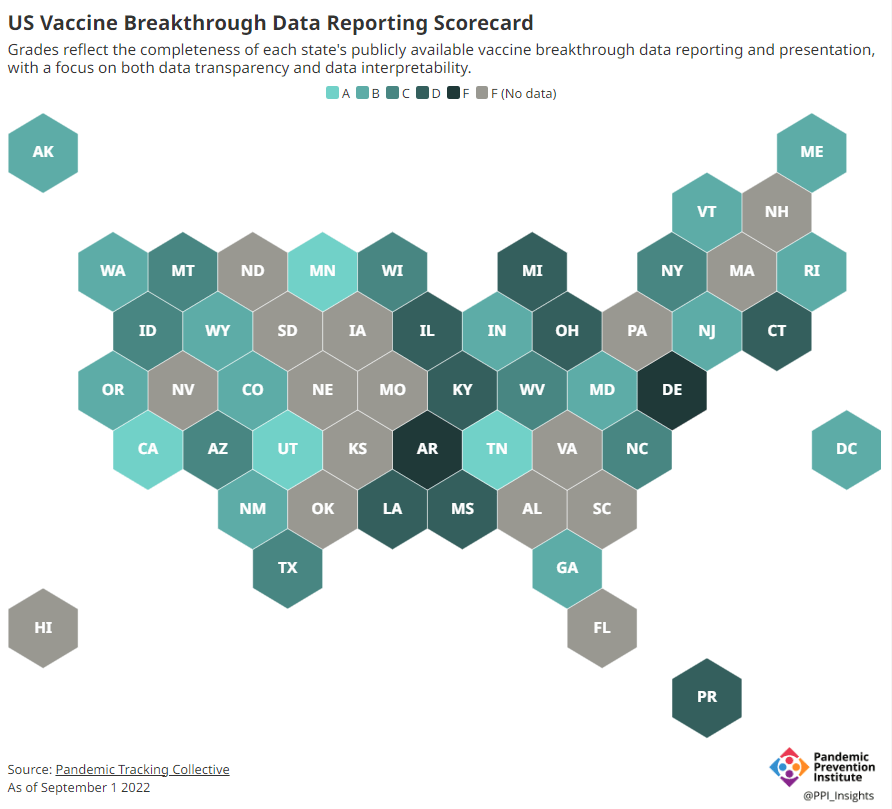

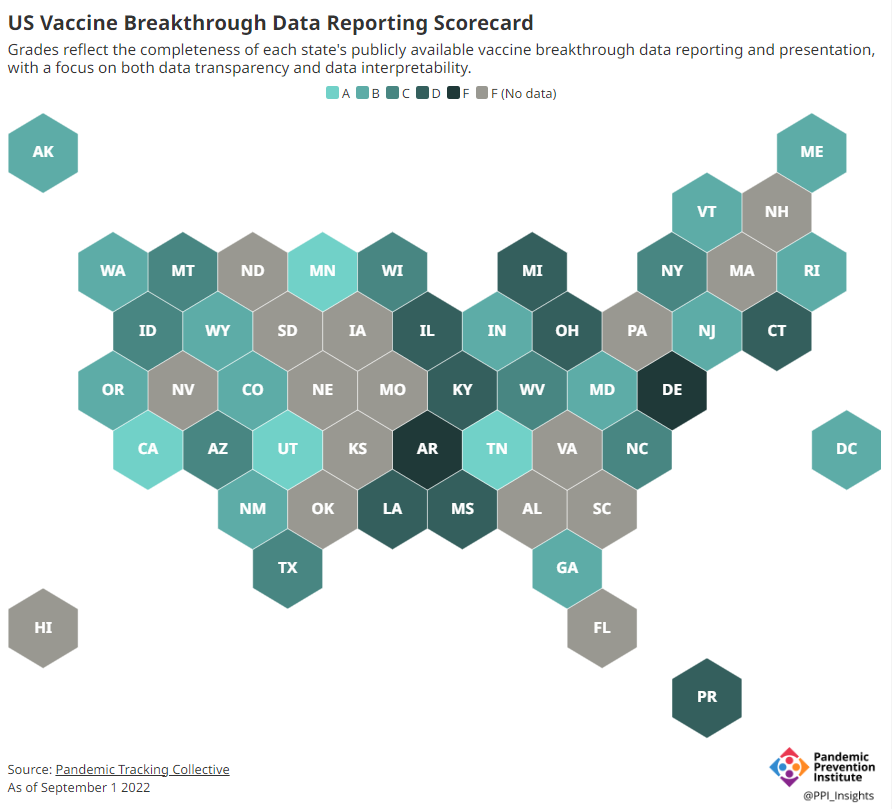

About half of U.S. states have D or F grades on their breakthrough case reporting, according to the Pandemic Prevention Institute and Pandemic Tracking Collective. Other metrics could be heading in this direction next year. COVID-19 is still a public health emergency. At the moment, this is true according to both the general definition of this term and official declarations by the federal government. But the latter could change in the coming months, likely leading to more fragmentation in U.S. COVID-19 data.

A reader recently asked me about the federal government’s ability to compile and report COVID-19 data, using our new anonymous Google form. They asked: “Will the CDC at some point stop reporting COVID data even though it may still be circulating, or is it a required, reportable disease?”

It’s difficult to predict what the CDC will do, as we’ve seen in the agency’s many twists and turns throughout the pandemic. That said, my best guess here is that the CDC will always provide COVID-19 data in some form; but the agency could be severely limited in data collection and reporting based on the disease’s federal status.

The CDC’s authority

One crucial thing to understand here is that the CDC does not actually have much power over state and local public health departments. It can issue guidance, request data, distribute funding, and so forth, but it isn’t able to require data collection in many circumstances.

Here’s Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at Harvard’s public health school and interim director of science at the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, explaining this dynamic. This quote is from an interview that I conducted back in May for my FiveThirtyEight story on the new center:

Outside of a public health emergency, CDC has no authority to require states to share data. And even in an emergency, for example, if you look on the COVID Data Tracker, there are systems that have half the states or some of the states. That’s because those were the ones that were willing to share. And that is a very big handicap of doing good modeling and good tracking… Everything you’re trying to measure, for any decision, is better if you measure it in all the states.

Consider breakthrough cases as one example. According to the Pandemic Prevention Institute’s scorecard for breakthrough data reporting, about half of U.S. states have D or F grades, meaning that they are reporting zero or very limited data on post-vaccination COVID-19 cases. The number of states with failing grades has increased in recent months, as states reduce their COVID-19 data resources. As a result, federal agencies have an incomplete picture of vaccine effectiveness.

Wastewater data is another example. While the CDC is able to compile data from all state and local public health departments with their own wastewater surveillance systems—and can pay Biobot to expand the surveillance network—the agency has no ability to actually require states to track COVID-19 through sewage. This lack of authority contributes to the CDC’s wastewater map still showing many empty spaces in states like Alabama and North Dakota.

The COVID-19 public health emergency

According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a federal public health emergency gives the HHS and CDC new funding for health measures and the authority to coordinate between states, among other expanded powers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal emergency was specifically used to require data collection from state health departments and individual hospitals, POLITICO reported in May. According to POLITICO, the required data includes sources that have become key to our country’s ability to track the pandemic, such as:

- PCR test results from state and local health departments;

- Hospital capacity information from individual healthcare facilities;

- COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals;

- COVID-19 cases, deaths, and vaccination status in nursing homes.

The federal COVID-19 public health emergency is formally controlled by HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra. Becerra most recently renewed the emergency in July, with an expiration date in October. Health experts anticipate that it will be renewed again in October, because HHS has promised to give states a 60-day warning before the emergency expires and there’s been no warning for this fall. That leaves us with a new potential expiration date in January 2023.

CDC officials are seeking to permanently expand the agency’s authority to include this data collection—with a particular priority on hospitalization data. But that hasn’t happened yet, to the best of my knowledge. So, what might happen to our data when the federal emergency ends?

Most likely, metrics that the CDC currently requires from states will become voluntary. As we see right now with breakthrough cases and wastewater data, some states will probably continue reporting while others will not. Our federal data will become much more piecemeal, a patchwork of reporting for important sources such as hospitalizations and lab test results.

It’s important to note here that many states have already ended their own public health emergencies, following a trend that I covered back in February. Many of these states are now devoting fewer resources to free tests, contact tracing, case investigations, public data dashboards, and other data-related efforts than they were in prior phases of the pandemic. New York was the latest state to make such a declaration, with Governor Kathy Hochul letting her emergency powers expire last week.

How the flu gets tracked

COVID-minimizing officials and pundits love to compare “endemic” COVID-19 to the flu. This isn’t a great comparison for many reasons, but I do think it’s helpful to look at how flu is currently tracked in the U.S. in order to get a sense of how COVID-19 may be tracked in the future.

The U.S. does not count every flu case; that kind of precise tracking on a large scale was actually a new innovation for COVID-19. Instead, the CDC relies on surveillance networks that estimate national flu cases based on targeted tracking.

There are about 400 labs nationwide (including public health labs in all 50 states) participating in flu surveillance via the World Health Organization’s global program, processing flu tests and sequencing cases to track viral variants. Meanwhile, about 3,000 outpatient healthcare providers in the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network provide the CDC with flu-related electronic health records. You can read more about both surveillance programs here.

Sample CDC flu reporting from spring 2020. The agency provides estimates of flu activity rather than precise case numbers. The CDC reports data from these surveillance programs on a dashboard called FluView. As you can see, the CDC provides estimates about flu activity by state and by different demographic groups, but the data may not be very granular (eg. no estimates by county or metro area) and are provided with significant time delays.

Other diseases are tracked similarly. For example, the CDC will track new outbreaks of foodborne illnesses like E. coli when they arise but does not attempt to log every infection. When researchers seek to understand the burden of different diseases, they often use hospital or insurance records rather than government data.

One metric that I’d expect to remain unchanged when the COVID-19 emergency ends is deaths: the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) comprehensively tracks all deaths through its death certificate system. But even provisional data from NCHS are reported with a delay of several weeks, with complete data unavailable for at least a year.

Epidemiologists I’ve interviewed say that we should be inspired by COVID-19 to improve surveillance for other diseases, rather than allowing COVID-19 to fall into the flu model. Wastewater data could help with this; a lot of wastewater researchers (including those at Biobot) are already working on tracking flu and other diseases. But to truly improve surveillance, we need more sustained investment in public health at all levels—and more data collection authority for the CDC and HHS.

More federal data

-

Two major Long COVID reports are coming in August

Two new White House/HHS reports about Long COVID and other long-term pandemic impacts will be released next month. Screenshot via Twitter. This past Friday, the White House and the Department of Health and Human Services held a briefing previewing two major reports about Long COVID.

The reports, which the Biden administration plans to release in August, will share government resources and research priorities for Long COVID, as well as priorities for other groups impacted long-term by the pandemic, such as healthcare workers and people who lost loved ones to COVID-19. Friday’s briefing served to give people and organizations most directly impacted by this work (particularly Long COVID patients) advanced notice about the reports and future related efforts.

It was also, apparently, closed to the press—a fact that I did not learn until I had already publicly livetweeted half of the meeting. I later confirmed with other journalist friends that the White House and HHS press offices did not do a great job of communicating the meeting’s supposedly closed status, as none of us knew this beforehand.

Officials honestly didn’t share much information at this briefing that I didn’t already know, so it’s not as though I obtained a huge scoop by watching it. (For transparency’s sake: I received a link to register for the Zoom meeting via the COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project’s listserv, and identified myself as a journalist when I signed up.)

Due to confusion around the briefing’s status and the fact that other attendees (besides myself) livetweeted it, I feel comfortable sharing a few key points from the call. If this gets me in trouble with the HHS press office, well… they’ve never answered my emails anyway.

Key points:

- These upcoming August reports are responding to a memorandum that the Biden administration issued in April calling for action on Long COVID.

- Over ten federal government agencies have been involved in producing the reports, which officials touted as an example of their comprehensive response to this condition.

- One report will focus on services for Long COVID patients and others facing long-term impacts from the pandemic. My impression is that this will mostly highlight existing services, rather than creating new COVID-focused services (though the latter could be developed in the future).

- The second report will focus on Long COVID research, providing priorities for both public and private scientific and medical research efforts. Worth noting: existing public Long COVID research is not going well so far, for reasons I have covered extensively.

- An HHS team focused on human-centered design has been pursuing an “effort to better understand Long COVID” (quoting from their web page). This project is currently wrapping up its first stage, and expects to publish a report in late 2022.

- Some Long COVID patients and advocates would like to see more urgent action from the federal government than what they felt was on display at this briefing.

Here are a couple of Tweets from advocates who attended:

I look forward to covering the reports when they’re released in August.

More Long COVID reporting

-

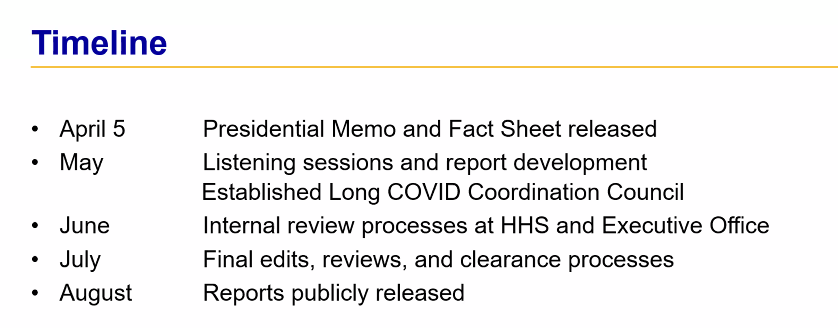

We need more data on who’s getting Paxlovid

Last week, I shared a new page from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), reporting statistics on COVID-19 therapeutic distribution in the U.S. The new dataset is a helpful step, but it falls far short of the information we actually need to examine who has access to COVID-19 treatments (particularly Paxlovid) and address potential health equity issues.

The HHS dataset includes total counts of COVID-19 drugs ordered and administered in the U.S., both nationally and by state. It also includes weekly numbers of the doses available for health providers to order from the federal government (which the HHS calls “thresholds”), over the last five weeks; again, these are available nationally and by state.

As most of the monoclonal antibodies developed for earlier variants do not provide much protection against Omicron, the majority of treatments used in the country last month were antiviral drugs Paxlovid (made by Pfizer) and Molnupiravir (made by Merck).

Paxlovid is the most effective of the two, and the most in-demand. In recent weeks, some patients have reported difficulties with accessing this antiviral as BA.2 drives rising cases across the country. For instance, one COVID-19 Data Dispatch reader wrote to me last week to share that a family member who should’ve been eligible for Paxlovid had his prescription denied, as his pharmacy said the drug was in “limited supply.”

In the first Omicron surge, during the winter, Paxlovid definitely was in limited supply. Then, as that surge waned, supplies improved: a Washington Post article last month reported that the federal government had plenty of doses going unused, and health leaders like COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha wanted to raise awareness of the antiviral with providers and patients.

Now, as BA.2 and its subvariants drive a new surge, it’s unclear whether there are still plenty of Paxlovid doses for anyone who might need them—or whether the doses must once again be rationed for only the most vulnerable patients. If the latter is true, even if it’s true only in some states or counties hardest-hit by the Omicron variants, it’s a problem: as the U.S. seems completely unwilling to put in new safety measures, Paxlovid is an important tool to at least reduce severe disease and death. Without it, high-risk people are in an even worse position.

As a data journalist, I would love to investigate this problem by digging into federal data to see where Paxlovid is getting used, and where there may be gaps. But the existing data are pretty sparse: the HHS has published only limited national and state-level data, with the only numbers on doses actually ordered and administered being cumulative (i.e. totals over a five-month period). There’s no information on how Paxlovid prescriptions have changed in different states or counties over time, or of whether the drug is actually reaching vulnerable people who need it.

KHN’s Hannah Recht explained why this data gap is a problem for health providers prescribing Paxlovid, in an article earlier in May:

Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Health has worked to ensure its 10 million residents, especially the most vulnerable, have access to treatment. When Paxlovid supply was limited in the winter, officials there made sure that pharmacies in hard-hit communities were well stocked, according to Dr. Seira Kurian, a regional health officer in the department. In April, the county launched its own telehealth service to assess residents for treatment free of charge, a model that avoids many of the hurdles that make treatment at for-profit pharmacy-based clinics difficult for uninsured, rural, or disabled patients to use.

But without federal data, they don’t know how many county residents have gotten the pills. Real-time data would show whether a neighborhood is filling prescriptions as expected during a surge, or which communities public health workers should target for educational campaigns.

Yasmeen Abutaleb’s article in the Washington Post (linked above) also discusses the need for data:

Other experts welcomed the administration’s efforts, especially as cases rise, but said simply boosting the supply wasn’t enough, noting that inequities persist in who has access to Paxlovid. People without health insurance and those who live far away from medical providers or pharmacies are among those at highest risk from covid and face some of the highest hurdles to receiving effective treatment, said Julie Morita, executive vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“It is essential that we collect and report data on who is receiving Paxlovid and other antiviral medications to swiftly pinpoint and address any disparities that emerge,” Morita said. “If done right, this can be a real turning point — but it is essential that all populations and communities have the opportunity to reap the benefits.”

In short, if health providers like community clinics and pharmacies could see data on which communities are receiving Paxlovid prescriptions and which ones are not, they could work to fill the gaps. The existing state-by-state data (published after Recht’s article) is a helpful starting point, but still has little utility for local health officials.

Indeed, the limited state-by-state data already suggest that some states in the Northeast, the West Coast, and the Great Lakes region are ordering and administering more Paxlovid (relative to their populations), compared to others in the Midwest and South. This is a pattern worth examining further, but it’s difficult when the data are so unspecific.

Here’s my wishlist of Paxlovid data that would be more useful:

- More granular geographies. State-level data is pretty useless if you run a local health clinic, or if you’re a local journalist. We need prescription information at the county level, if not even smaller regions (like census tracts or ZIP codes.)

- Demographic data. Without data on race and ethnicity, age, or other demographic factors, it’s very difficult to determine whether Paxlovid is reaching people in an equitable way—or if access to the drug is becoming another way in which the pandemic disproportionately impacts already-marginalized groups.

- Provider type. Along the same lines as demographic data, seeing how many Paxlovid doses are going through large pharmacies as opposed to community health centers, hospitals, or other types of healthcare providers could be a useful measure of equity.

- Patient health conditions. People with health conditions that predispose them to severe COVID-19 symptoms (compromised immune systems, diabetes, kidney disease, etc.) are supposed to be at the front of the line for Paxlovid. We need data to see whether they are actually getting this priority treatment.

Come on, HHS: give us the granular data!

More federal data

-

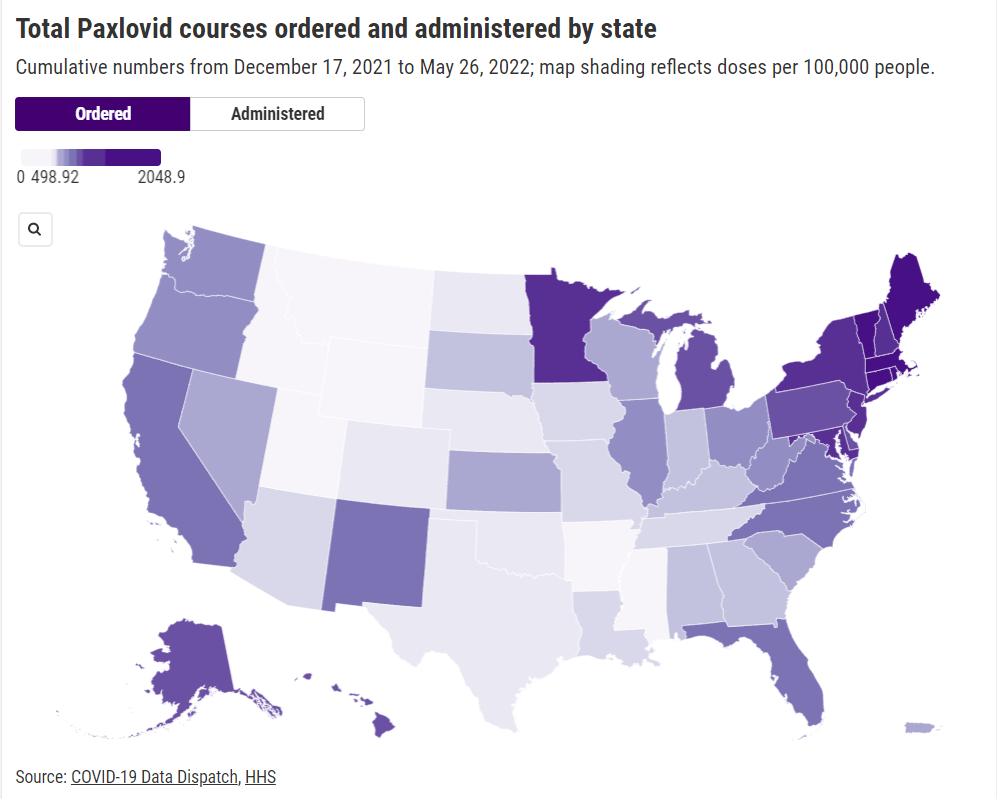

Hospitalization data lag behind the actual crisis

A record number of COVID-19 patients are now receiving care in U.S. hospitals, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). As of January 16, the agency reports that about 157,000 COVID-19 patients are currently hospitalized nationwide, and one in every five hospitalized Americans has been diagnosed with this disease.

The HHS also reports that about 78% of staffed hospital beds and 82% of ICU beds are currently occupied. These numbers, like the total COVID-19 patient figure, are higher than they have been at any other point during the pandemic.

Even so, reports from the doctors and other staff working in these hospitals—conveyed in the news and on social media—suggest that the HHS data don’t capture the current crisis. The federal data may be reported with delays and fail to capture the impact of staffing shortages, obscuring the fact that many regions and individual hospitals are currently operating at 100% capacity.

Dr. Jeremy Faust, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor at Harvard Medical School, recently made this argument in Inside Medicine, his Bulletin newsletter. Last week, I shared Faust and colleagues’ circuit breaker dashboard, which extrapolates from both federal hospitalization figures and current case data to model hospital capacity in close-to-real-time. This week, Faust used that dashboard to show that the crisis inside hospitals is more dire than HHS numbers suggest.

He writes:

There seems to be a disconnect between the official data made available to the public and what’s happening on the ground. The reason for this is unacceptable delays in reporting. HHS and other agencies have always acknowledged that public reports on hospital capacity—for Covid-19 and all other conditions—actually reflect data that are 1-2 weeks old. But until now, such lags rarely mattered because most hospitals haven’t had to operate near or above 100% capacity routinely, even during the pandemic. Under normal circumstances, whether a hospital was 65% or 75% full does not make much of a difference, though as the numbers creep up, care can be compromised. And even in past moments when capacity was closer to 100%, a wave of Omicron-driven Covid-19 was not headed towards hospitals.

For example: on Monday, Faust wrote, his team’s circuit breaker dashboard showed that “every single county in Maryland appears to be over 100% capacity,” even though the HHS said that 87% of hospital beds were occupied in the state. Healthcare workers in Maryland backed up the claim that all counties were over 100% capacity, with personal accounts of higher-than-ever cases and hospitals going into crisis standards.

On Thursday, Faust shared an update: the circuit breaker dashboard, at that point, projected that hospitals in Arizona, California, Washington, and Wisconsin were approaching 100% capacity, if they weren’t at that point already. As of Saturday, California and Arizona are still projected to be at “at capacity,” according to the dashboard, while 14 other states ranging from Montana to South Carolina are “forecasted to exceed capacity” in coming days.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1642354079303’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’1087px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’1736px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’1087px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’1736px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’3027px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);From Faust’s descriptions and the accounts of healthcare workers he quotes, it’s also evident that determining between hospitalizations “with” COVID-19 and hospitalizations “from” COVID-19 is not a useful way to spend time and resources right now. Even if some of the COVID-19 patients currently in U.S. hospitals “happened to test positive” while seeking treatment for some other condition, these patients are still contributing to the intense pressure our healthcare system is under right now.

Plus, as Ed Yong explains in a recent article in The Atlantic describing this false patient divide, COVID-19 can worsen other conditions that at first seem unrelated:

The problem with splitting people into these two rough categories is that a lot of patients, including those with chronic illnesses, don’t fit neatly into either. COVID isn’t just a respiratory disease; it also affects other organ systems. It can make a weak heart beat erratically, turn a manageable case of diabetes into a severe one, or weaken a frail person to the point where they fall and break something. “If you’re on the margin of coming into the hospital, COVID tips you over,” Vineet Arora, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago Medicine, told me. In such cases, COVID might not be listed as a reason for admission, but the patient wouldn’t have been admitted were it not for COVID.

In short: Omicron might be a milder variant at the individual level—thanks to a combination of the variant’s inherent biology and protection from vaccines and prior infections—but at a systemic level, it’s devastating. And rather than asking hospitals to split their patients into “with” versus “from” numbers, we should be giving them the staff, supplies, and other support they need to get through this crisis.