In the reader survey I sent out a few weeks ago, I asked, “What is one question you have about COVID-19 in the U.S. right now?” One reader responded with an inquiry into vaccine equity: “What will it look like when the U.S. is ‘open’ and vaccinated and many other parts of the world are not?”

That question feels especially relevant this week. On Thursday, the Biden administration made a big (and long-awaited) announcement: the federal government is sending 25 million vaccine doses from America’s stockpile to other countries. The administration has previously promised to send at least 80 million doses abroad by the end of June, but this week’s announcement included more details—such as countries that will receive these initial doses and other logistics.

Out of the 25 million, about 19 million doses are going to COVAX. COVAX, a global effort run by the World Health Organization and other international government bodies and philanthropic organizations, brings vaccines to low-income nations at no cost. The COVAX doses will go to India, other parts of Asia, Central and South America, and Africa, Bloomberg’s Josh Wingrove reports.

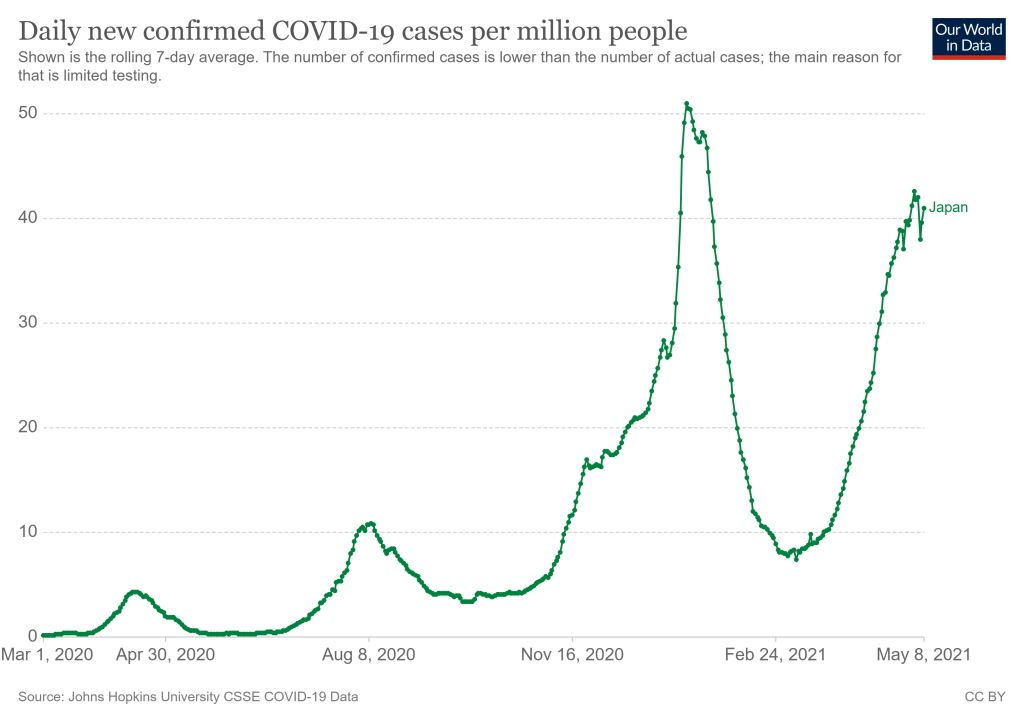

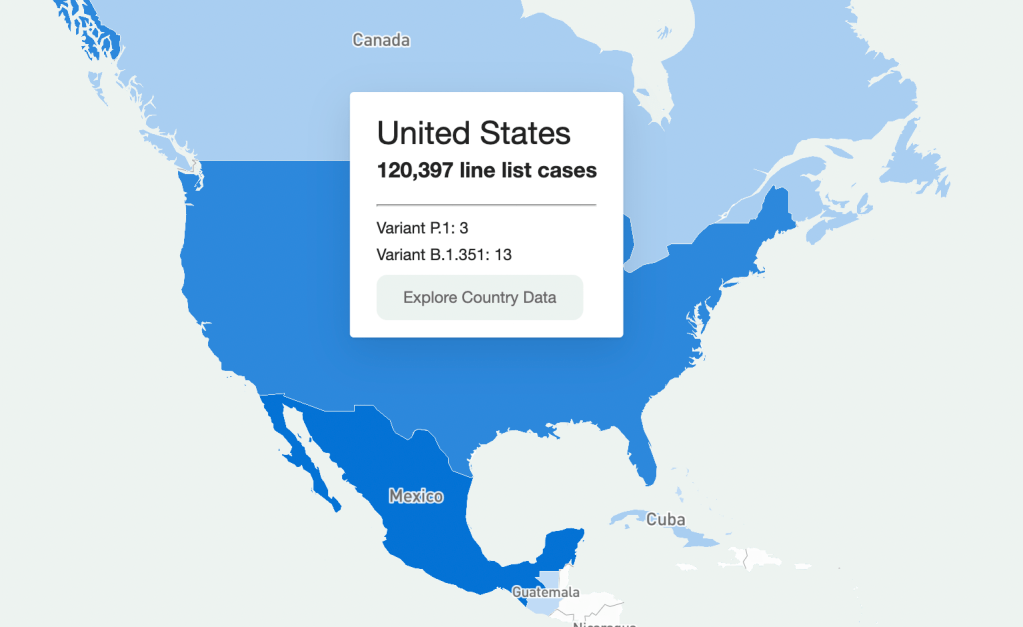

The remaining 6 million doses will be sent directly to countries, including Ukraine, Kosovo, Haiti, Georgia, Egypt, Jordan and Iraq. Some doses are going directly to India as well—while the worst of this nation’s surge may be over, it’s still facing high case counts, full hospitals, and a terrifying “black fungus” linked with the Delta variant (B.1.617).

At first glance, this might seem like a noble move on the Biden administration’s part. The U.S. is seeing low case numbers and widespread reopenings, so we can share some supplies to “help the pandemic around the globe,” as COVID-19 response coordinator Jeff Zients said at a briefing on Thursday.

But 25 million doses—or even the 80 million doses that the administration has promised by the end of this month—is a drop in the bucket compared to actual international needs. For example: COVAX needs 1.8 billion doses to vaccinate about half the adult population in low-income countries. COVAX has specifically prioritized 92 low-income nations, representing a total population of 3.8 billion.

That 1.8 billion dose number is a highlight of a major report released last week by the Rockefeller Foundation, a global charitable foundation, discussing what it would take to vaccinate the world. I covered the report for Science News. According to this report, Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance), an international public-private body that runs COVAX, needs to raise $9.3 billion in order to pay for those 1.8 billion doses. Gavi has been working to raise this money from countries and independent donors at a global health summit this past week.

While $9.3 billion might seem like a massive price tag, the cost of failing to provide these vaccines would actually be far greater. The global economy may lose up to $9.2 trillion if richer nations fail to support equitable vaccine distribution, according to an estimate from the International Chamber of Commerce.

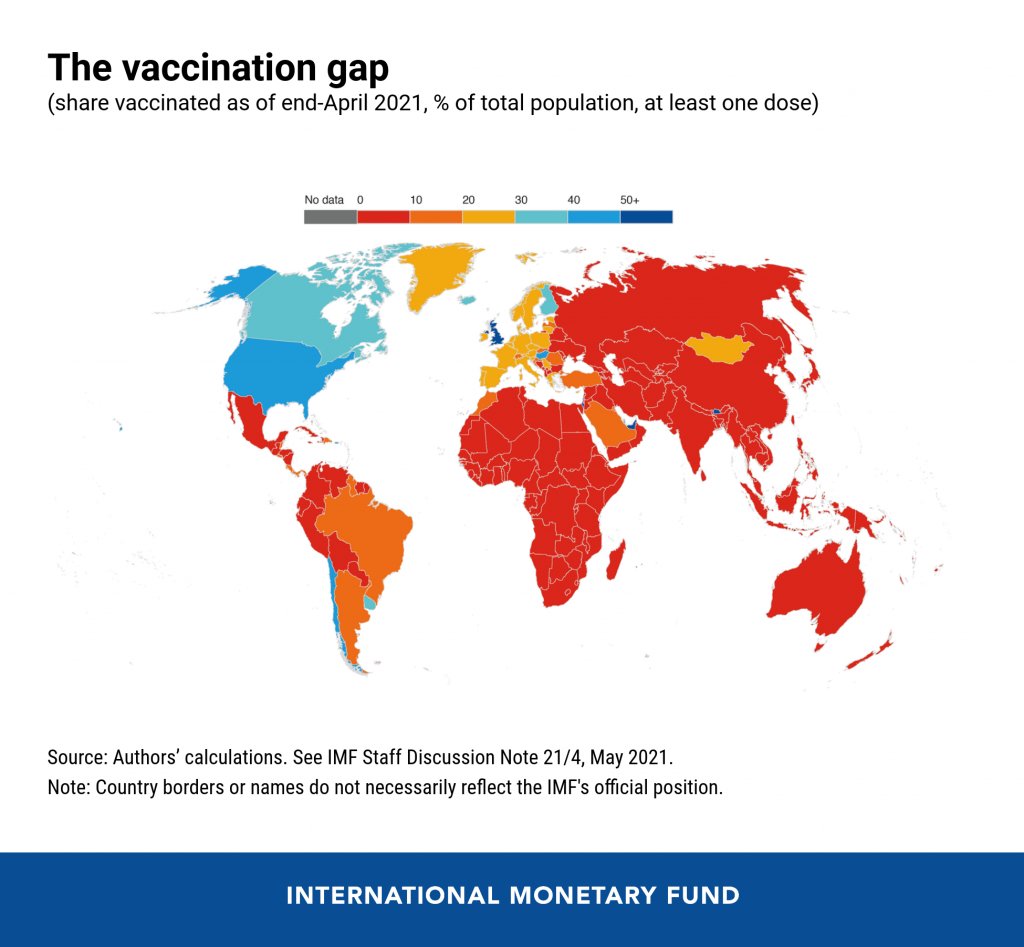

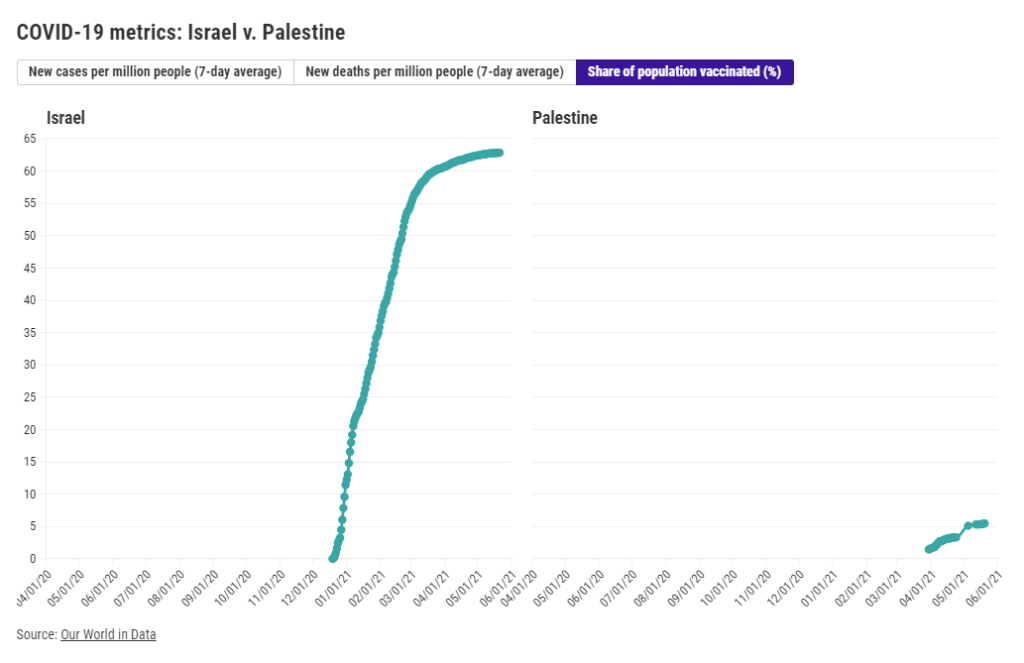

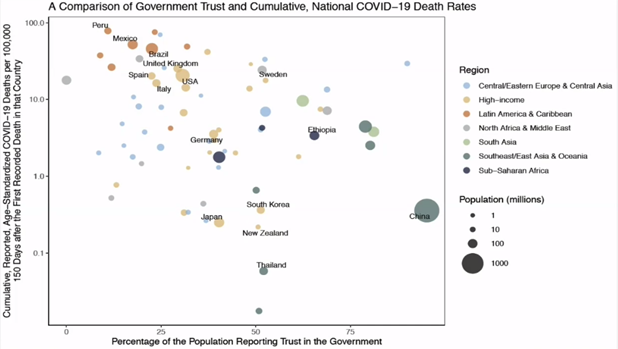

So far, the U.S. has administered about 300 million vaccine doses (as of yesterday), covering over half the total population. In a number of low-income countries, less than one percent of the population has received a dose. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the WHO, said at a recent assembly that, if all doses administered globally had been sent out equitably, the doses would have covered “all health workers and older people.” Instead, high-income nations are largely protected while low-income nations are vulnerable to future surges and highly-transmissible variants.

Through this lens, the 25 million dose shipment announced this week is far from impressive. It’s a useful start, certainly, but it’s not going to end the pandemic anywhere. Even the 80 million doses promised by the end of June is a tiny number—about 4% of the doses COVAX is hoping to obtain. It’s also only 11% of the doses that vaccine makers have pledged to deliver to the U.S. by the end of July, according to Bloomberg.

That larger June shipment has also been held up because the Biden administration is planning to send AstraZeneca vaccines—which are under review from the FDA because they were produced at the Emergent factory that infamously wasted millions of Johnson & Johnson doses. The AstraZeneca vaccine is not authorized for use in the U.S., so of course it will make up the majority of the doses we send abroad this summer.

Speaking of unused doses: the Biden administration may also start sending unused doses from states to other countries, POLITICO reported this week. The administration wants to get thousands of Pfizer, Moderna, and J&J doses—on the verge of expiring—to countries that would actually use them. While this possible policy hasn’t yet been realized, it hammers home a clear message: the U.S. will donate “unwanted” vaccine doses only when we are absolutely certain that we don’t need them here.

Now, let’s return to our reader’s question. What happens when the U.S. is safely vaccinated, but other parts of the world aren’t?

From a health standpoint, the U.S. will probably be okay. The vaccines are very effective, even against variants—likely protecting the country from another major surge. We will need careful surveillance to guard against future variants that may evolve beyond the vaccines (see: last week’s issue), and it’s possible that overly zealous reopening this summer will lead to outbreaks next fall and winter. But seniors and other vulnerable people would be more protected than they have been in past surges, and booster shots (for the variants) will likely be on their way soon. In short, America’s wealth will protect us.

Around the world, however, outbreaks will continue. Every time a new person gets infected with the coronavirus, the virus has a new opportunity to mutate. And with every mutation, the virus learns to spread faster, to evade common treatments, even to evade vaccines. Thanks to globalization, as long as the virus is a threat anywhere, it continues to be a threat everywhere.

Plus, as low-income nations suffer from continued outbreaks, the global economy will continue to suffer. Out of that $9.2 trillion cost estimated by the International Chamber of Commerce, the majority will likely fall on wealthier nations (like the U.S.) that rely on other countries for products and labor.

“The pandemic itself has gone beyond a health crisis — it has now gone into an economic crisis,” Christy Feig, the Rockefeller Foundation’s director of communications and advocacy, told me when I spoke to her for Science News. “The only way to unchoke the economy is by getting the vaccines to as many countries as possible, so that we can stop the spread of the disease before more variants come.”

(P.S. If you’d like to read more on how the pandemic may end in the U.S. and elsewhere, I recommend this story by STAT’s Helen Branswell.)