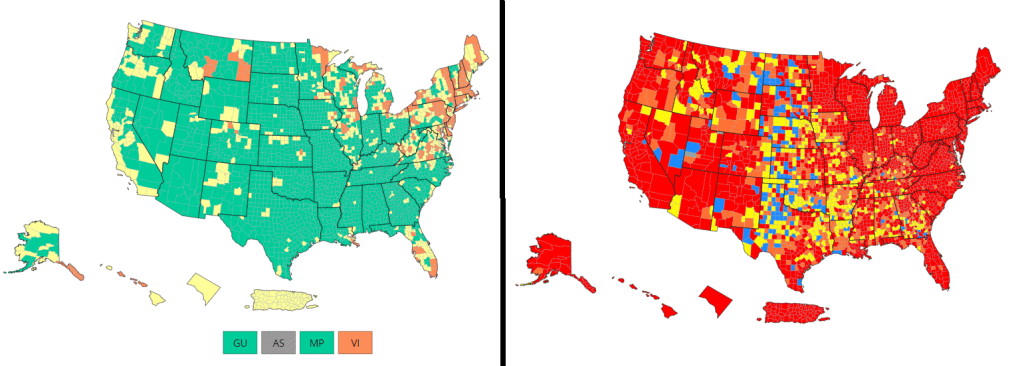

Anyone who’s been regularly reading the COVID-19 Data Dispatch for the last few weeks can probably tell that I think the CDC’s Community Levels are pretty useless. I was critical of these new metrics when the agency changed its guidance from the old Community Transmission Levels back in February. And during the BA.2 surge, I’ve pointed out how the CDC’s Community Levels map makes it look like the U.S. is doing fine at managing COVID-19 when, in fact, we are doing anything but.

If you need a refresher, here are a few of the problems with the Community Levels:

- The guidance overly uses hospitalization metrics; while these metrics (especially hospital admissions) are very reliable in showing COVID-19’s impact on the healthcare system, they lag behind actual infections and completely ignore Long COVID.

- Hospitalizations are actually a regional metric, not a county-level metric (since plenty of U.S. counties do not have hospitals). As a result, the CDC’s Community Levels calculations are confusing and difficult to replicate in some places.

- Thresholds in the Community Levels system, already using lagging indicators, are set very high—to the point that, by the time a county reaches the high level, its healthcare system is already in big trouble.

- The CDC does not recommend universal masking until a county reaches the high level; it only recommends one-way masking for vulnerable people, which we know doesn’t really work, at lower levels.

Essentially, these Community Levels are so lenient that many state and local leaders have taken the guidance as an excuse to avoid instituting new COVID-19 safety measures during the BA.2 surge. In Philadelphia, business owners even cited the CDC’s lenient guidance when suing the city for instituting a new indoor mask mandate.

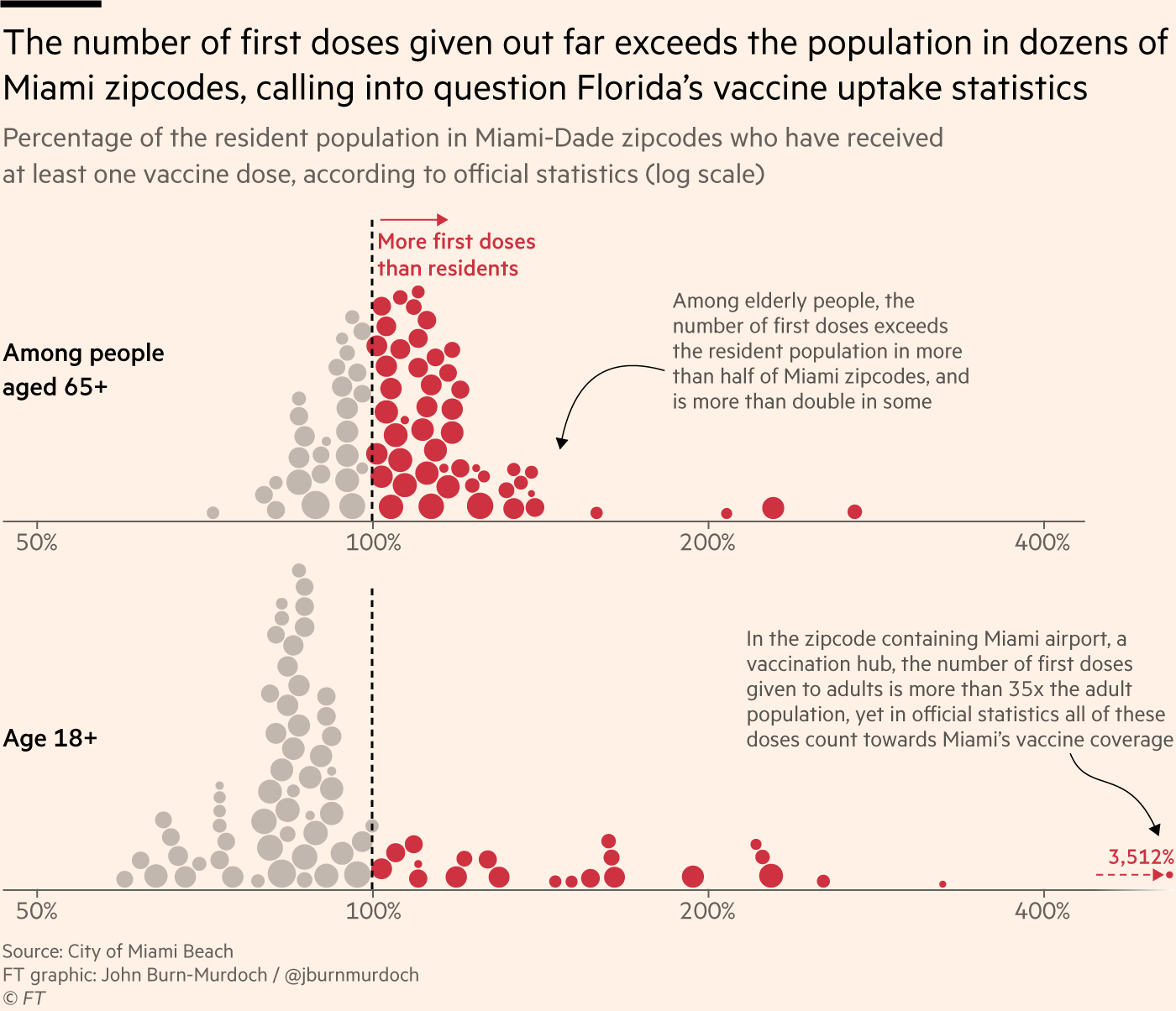

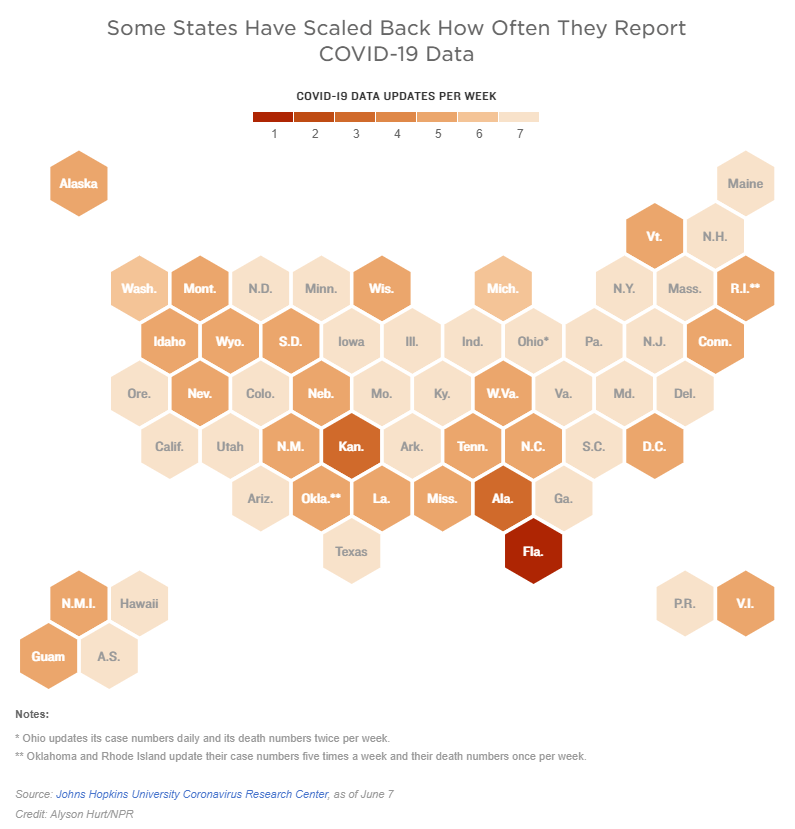

Moreover, as revealed by a recent article in the Tampa Bay Times, it appears that the CDC is not even consistent with its calculations of these Community Levels. The agency labeled three Florida counties as at medium COVID-19 risk, even though they met all the criteria for high risk, due to a data reporting issue from the Florida state health department.

To quote from the article: “A public health tool isn’t useful if it can be undone by a single data issue, said University of South Florida virologist Michael Teng.”

Reminder, you can still see the CDC’s old Community Transmission Level guidance (which is somewhat more useful for determining one’s actual COVID-19 risk) on the agency’s COVID-19 data portal. Just click the dropdown menu on the county view tab and select Community Transmission Levels.