In the most recent episode of comedy podcast My Brother, My Brother and Me (approx. timestamp 23:50), youngest brother Griffin McElroy solemnly asks, “Is Dr. Anthony Fauci on Cameo?”

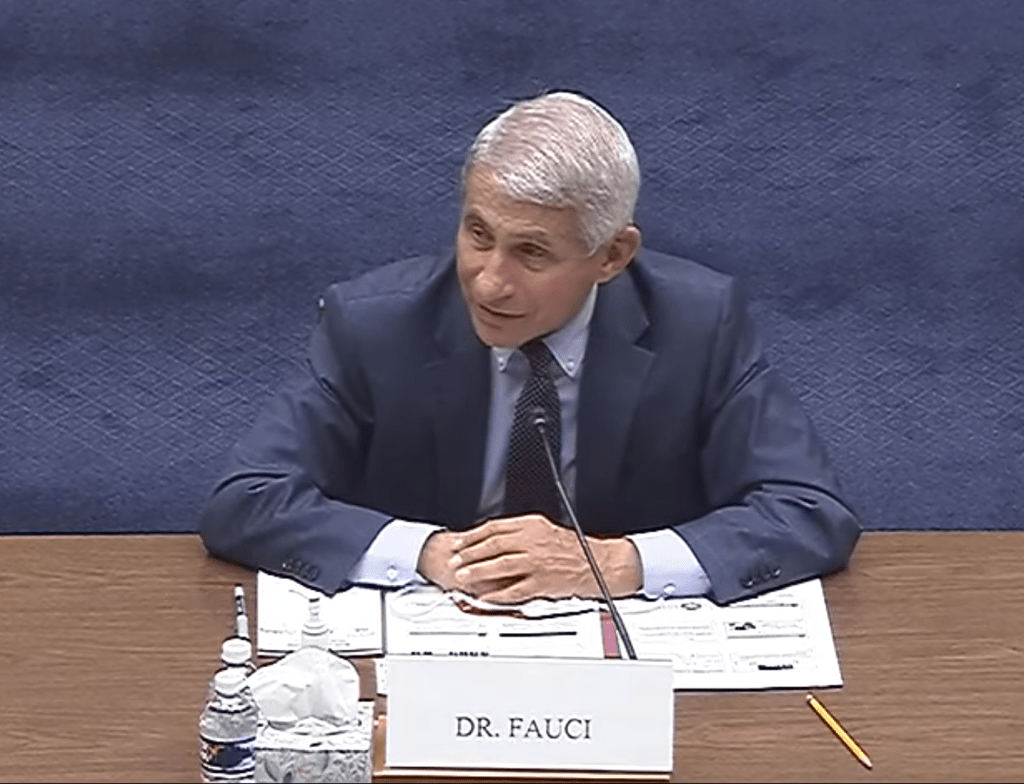

McElroy’s question, asked in the context of a rather silly and unscientific discussion on contaminated basketballs, refers to a video-sharing service in which fans can pay celebrities to send personalized messages. Dr. Fauci is, of course, not on Cameo. But he did make a public appearance this past Friday: he testified before the House Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis. This was Dr. Fauci’s first Congressional appearance in several weeks; Democrats have claimed that the White House blocked him from testifying earlier in the summer.

Dr. Fauci was joined on the witness stand by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Director Dr. Robert Redfield and Assistant Secretary for Health Admiral Brett Giroir, who leads policy development at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). All three witnesses answered questions about their respective departments, covering COVID-19-related topics from test wait times to the public health implications of Black Lives Matter protests.

For comprehensive coverage of the hearing, you can read my Tweet thread for Stacker:

But here, I will focus on five major takeaways for the COVID-19 data world.

First: the results of scientific studies on the pandemic are publicly shared. In his opening statement, Dr. Fauci cited four top priorities for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): improving scientific knowledge of how the novel coronavirus works, developing tests that can diagnose the disease, characterizing and testing methods of treating patients, and developing and testing vaccines. The Congressmembers on the House subcommittee were particularly interested in this last priority; Dr. Fauci reassured several legislators that taking vaccine development at “warp speed” will not come at the cost of safety.

Rep. Jackie Walorski, a Republican from Indiana, was especially concerned about Chinese interference in vaccine development. She repeatedly asked Dr. Fauci if he believed China was “hacking” American vaccine research, and if he believed this was a threat to the progress of such work. Dr. Fauci replied that all clinical results from NIAID work are shared publicly through the usual scientific process, to invite feedback from the greater medical community.

Clinical studies in particular are listed in a National Institutes of Health (NIH) database called ClinicalTrials.gov. On this site, any user can easily search for studies relating to COVID-19; there are2,844 listed at the time I send this newsletter. 256 of these studies are marked as “completed,” and two of those have results posted. I see no reason to doubt that, if Rep. Walorski were to visit this database in the coming months, she would find the results of vaccine trials here as well.

Dr. Fauci also publicized the COVID-19 Prevention Network, a website on which Americans can volunteer for vaccine trials. According to Dr. Fauci, 250,000 individuals had registered by the time of the hearing.

Second: nursing homes are getting COVID-19 antigen tests, big time. Dr. Redfield, Admiral Giroir, and several of the House representatives at the hearing highlighted a recent initiative by HHS to distribute rapid diagnostic COVID-19 tests to nursing homes in hotspot areas. In his opening remarks, Dr. Redfield stated that, by the end of this week, federal health agencies will have delivered “nearly one million point-of-care test kits to 1,019 of the highest risk nursing homes, with 664 nursing homes scheduled for next week.”

The tests being distributed identify antigens, protein fragments on the surface of the novel coronavirus. Like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, antigen tests determine if a patient is infected at the time they are tested; unlike PCR tests, they may be produced and distributed cheaply, and return results in minutes. Antigen tests have lower sensitivity, however, meaning that they may miss identifying patients who are in fact infected.

The antigen test distribution initiative is great news for the nursing homes across the country that will be able to test and treat their residents more quickly. But from a data perspective, it poses one major question: how will the results of these tests be reported? While antigen tests may be diagnostic, their results should not be lumped in with PCR test results because they have a different accuracy level and serve a different purpose in the pandemic.

The Nursing Home COVID-19 Public File, a national dataset run by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, reports “confirmed” and “suspected” COVID-19 cases in the nation’s nursing homes. The dataset does not specify what types of tests were used to identify these cases, or the total tests conducted in each home. Similarly, state-reported datasets on COVID-19 in nursing homes typically report only cases and deaths, not testing numbers. And, as of the most recent COVID Tracking Project analysis, the only state currently reporting antigen tests in an official capacity is Kentucky. But more states may be including antigen test numbers in their counts of “confirmed cases” or “molecular tests,” as several states lumped PCR and serology tests this past spring. As hundreds of nursing homes across the country begin to use the antigen tests so graciously distributed by the federal government, we must carefully watch to identify where those numbers show up.

Third: Admiral Giroir doesn’t know what data his agency publishes.

If you watch just five minutes from Friday’s hearing, I highly recommend the five minutes in which Rep. Nydia Velázquez (a Democrat from New York) interrogates Admiral Giroir about COVID-19 test wait times. Here’s my transcript of a key moment in the conversation:

Rep. Velázquez: Dr. Redfield, I’d like to turn to you. Does the CDC have comprehensive information about the wait times for test results in all 50 states?

Dr. Redfield: I would refer that question back to the Admiral.

Rep. Velázquez: Sir?

Admiral Giroir: Yes, we have comprehensive information on wait times in all 50 states, from the large, commercial labs.

Rep. Velázquez: And do you publish this data? These data?

Admiral Giroir: Uh… we talk about it. Always. I mean, I was on… I was with 69 journalists yesterday, and we talk about that frequently.

He went on to claim that decisionmakers at the state and city level have data on test wait times from commercial labs. But where are these data? HHS has collected testing data since the beginning of the pandemic; these data were first published on a CDC dashboard in early May and are now available on HealthData.gov.

The HealthData.gov dataset includes test results from CDC labs, commercial labs, state public health labs, and in-house hospital labs. For each test, the dataset includes geographic information, a date, and the test’s outcome. It does not include the time between the test being administered and its results being reported to the patient. In fact, that “date” can either be a. the date the test was completed, b. the date the result was reported, c. the date the specimen was collected, d. the date the test arrived at a testing facility, or e. the date the test was ordered. So, if there’s another, secret dataset which includes more precise dating, I personally would love to see it made public.

Also, who are those 69 journalists, Admiral Giroir? How do I join those ranks? I have some questions about HHS hospitalization data.

Fourth: everyone wants to reopen schools. Dr. Redfield said, opening schools is “in the best public health interest of K-12 students.” Dr. Fauci said, schools should reopen so that schools can access health services, teachers can identify instances of child abuse, and to avoid “downstream unintended consequences for families.” Rep. Steve Scalise, the subcommittee’s Ranking Member (and a Republican from Louisiana, home to one of the country’s most annoying COVID-19 dashboards), said, “Don’t deny these children the right to seek the American dream that everybody else has deserved over the history of our country.” Rep. James Clyburn, the subcommittee’s Chair (a Democrat from South Carolina), said that school reopening must not be a “one size fits all approach,” but it should be done for the good of students and their families.

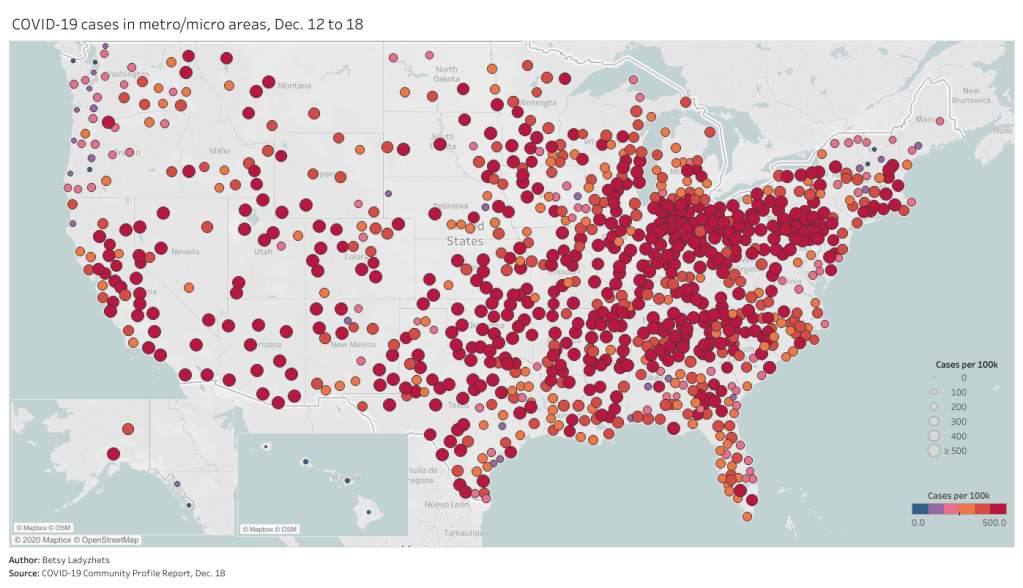

Clearly, reopening schools is a popular political opinion. But does the country have the data we need to determine if schools can reopen safely? Reopening, as Dr. Fauci explained in response to an early question from Rep. Clyburn, is most safely done when COVID-19 is no longer circulating widely in a community. School districts can determine whether the disease is circulating widely through looking at case counts over time, but for those case counts to be accurate, the region must be doing enough testing and contact tracing to catch all cases.

And testing data, while they are certainly collected at the county and zip code levels by local public health departments, are not standardized at all. HHS doesn’t publish county-level testing data. Nor does the COVID Tracking Project. This lack of standardization for any geographic region smaller than a state is troubling, as public health leaders and journalists alike cannot currently assess the scope of local outbreaks with any kind of broad comparison. To put it simply: I would love to do a story on how many school districts can safely reopen right now, based on their case counts and test metrics. But the data I would need to do this story do not exist.

Fifth: all data are political; COVID-19 data are especially political. I know, I know. Data have been political since humans started collecting them. One of America’s most comprehensive data sources, the U.S. Census, started as a way to enforce the Three-Fifths Compromise.

But watching this Friday’s hearing hammered home for me how the mountains of data produced by this pandemic, coupled with the complete lack of standards across the institutions producing them, has made it particularly easy for politicians to quote random numbers out of context in order to advance their agendas. Rep. Clyburn said, “At least 11 states… are currently performing less than 30% of the tests they need to control the virus.” (Which states? How many tests do they need to perform? Where di that benchmark come from? What other metrics should the states be following?) And, on the other side of the aisle, Rep. Scalise held up a massive stack of paper and waved it right at the camera, claiming that the high number of tests that have been conducted in this country is evidence of President Trump’s national plan. (But how many tests have we conducted per capita? What are the positivity rates? What statistics can we actually correlate to President Trump’s plan?)

In fact, after the hearing, the White House put out a press release claiming that America has “the best COVID-19 testing system in the world.” The briefing includes such claims as, “the U.S. has already conducted more than 59 million tests,” and, “the Federal Government has distributed more than 44 million swabs and 36 million tubes of media to all 50 States.” None of the statistics in the briefing are put into terms reflecting how many people have actually been tested, compared to the country’s total population. And none of the statistics are contextualized with public health information on what targets we should be meeting to control the pandemic.

The experts who might have been consulted on that brief—Dr. Fauci, Dr. Redfield, and Admiral Giroir—all sat before Congressional Representatives on Friday morning, quietly nodding when Representatives asked if their respective departments were doing everything possible to protect America. If they had answered otherwise, they may not have returned for future hearings. The whole thing felt very performative to me: the Democrats threw veiled jibes at President Trump, the Republicans bemoaned China and Black Lives Matter protests, and Dr. Fauci fact-checked such basic statements as, “Children are not immune to COVID-19.”

And almost everyone in the room—including all three witnesses—removed their mask when they spoke.

If Dr. Fauci were available to commission on the video service Cameo, I would pay him good money to send a personal message to every Congressmember on that subcommittee telling them, confidentially, exactly what he thinks of their questions. And then I would ask him for Admiral Giroir’s personal cell phone number.