- Medicaid coverage losses by state: KFF Health News published a story this week sharing new data on the Americans who lost Medicaid coverage due to the end of a COVID-19 policy that prevented states from kicking people off the insurance during earlier stages of the pandemic. More than 600,000 people in 14 states have lost coverage since April 1, according to reporter Hannah Recht’s analysis. That represents about 36% of the people whose Medicaid eligibility was up for review in these states, though the number is much higher in some states (about 80% in Oklahoma). Recht also published the underlying data from her analysis for other reporters to use.

- Library of Congress COVID-19 history project: The Library of Congress has announced a new project to collect COVID-19 oral history stories, partnering with the StoryCorps interview archive. Congress has provided funding for the COVID-19 project, which will provide grants to researchers working to document the experiences of specific groups. This project is focusing on frontline workers and the survivors of people who died from COVID-19, but other Americans are welcome to share their stories through the StoryCorps website.

- Children often cause household COVID-19 spread: Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and Kinsa, a health tech company, used data from smart thermometers to track how the coronavirus spreads inside households. Among about 39,000 instances of household transmission, a child was the initial case 70% of the time. The study suggests that children are major drivers of disease spread, especially during the school year; it also demonstrates the potential utility of smart thermometer data. (For more about Kinsa, see this post from last fall.)

- Disproportionate COVID-19 impacts within a city: Another study that caught my attention this week: researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and collaborators evaluated how severe COVID-19 impacts differed by ZIP code within the city of Austin. Their analysis found that ZIP codes with more vulnerable populations (based on the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index) had higher rates of COVID-19 cases, but were less likely to have their cases reported. When limited surveillance data are available, the researchers suggest, health agencies should direct resources to more vulnerable communities.

- Assessing who’s not connected to public sewers: One commonly-cited limitation of wastewater surveillance data is that about one in five U.S. households aren’t connected to public sewers. A new preprint from scientists at Harvard University and Biobot Analytics looks at this issue in more detail, using publicly available datasets describing sewer connectivity. The researchers found that, overall, some demographic groups (such as Native Americans, wealthier people in rural areas, etc.) are less likely to be connected to public sewers, as are some regions (such as Alaska and Navajo Nation). But public datasets have many gaps and biases, making it challenging to thoroughly assess this problem. Lead author QinQin Yu has a Twitter thread with more details.

Tag: Contact tracing

-

Sources and updates, June 4

-

Sources and updates, July 17

- COVID-19 and antimicrobial resistance: The pandemic resulted in major losses for the fight against antimicrobial resistance, according to a new CDC report published last week. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), in which bacteria evolve the ability to bypass commonly-used antibiotics, is a significant public health concern in the U.S. and globally. The CDC is still missing data for several major AMR threats during the pandemic, but data the agency was able to compile present a concerning picture about resistant infections in U.S. hospitals during the pandemic.

- CDC’s air travel contact tracing needs work: And now, a report about the CDC: the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the agency’s data system for contact tracing on flights “needs substantial improvement.” Without a comprehensive, singular data source for airplane passenger contact information, the CDC has to do extra research and extend contact tracing time after a passenger tests positive for COVID-19.

- State COVID-19 data reporting continues slowing: New York Times reporter Adeel Hassan and colleagues described how states are reporting their COVID-19 data less frequently and closing public testing sites, leaving more gaps and delays in their numbers. This article provides a helpful summary of a trend I’ve alluded to in various blog posts for the last few weeks.

- Private companies step up to assist with PCR testing: Two major testing companies, Quest Diagnostics and Color Health, announced this week that they will provide free COVID-19 testing to some Americans without health insurance at hundreds of sites across the country; these site locations will be determined by the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. The CDC is picking up the tab for these testing costs, according to press releases. (H/t the COVID Weekly Testing Newsletter.)

- FDA authorization for Novavax vaccine: Novavax’s protein-based COVID-19 vaccine has been granted Emergency Use Authorization by the FDA. While this vaccine option is unlikely to substantially increase uptake in the U.S., the FDA’s authorization opens the door for Novavax shots to be used as fall booster shots—an idea that seemed promising to some members of the agency’s advisory committee in a recent meeting.

-

Five more things, February 20

A few additional news items from this week:

- Omicron has caused more U.S. COVID-19 deaths than Delta. Despite numerous headlines proclaiming the Omicron variant to be “milder” than previous versions of the coronavirus, this variant infected such a high number of Americans that it still caused more deaths than previous waves, a new analysis by the New York Times shows. Between the end of November and this past week, the U.S. has reported over 30 million new COVID-19 cases and over 154,000 new deaths, the NYT found, compared to 11 million cases and 132,000 deaths from August 1 through October 31 (a period covering the worst of the Delta surge).

- 124 countries are not on target to meet COVID-19 vaccination targets. The World Health Organization (WHO) set a target for all countries worldwide to have 70% of their populations fully vaccinated by mid-2022. As we approach the deadline, analysts at Our World in Data estimated how many countries have already met or are on track to meet the goal. They found: 124 countries are not on track to fully vaccinate 70% of their populations, including the U.S., Russia, Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, and other large nations.

- Anime NYC was not an omicron superspreader event, CDC says. In early December, the Minnesota health department sounded the alarm about a Minnesotan whose COVID-19 case had been identified as Omicron—and who had recently traveled to New York City for the Anime NYC convention. The CDC investigated possible Omicron spread at this event, both by contact tracing the Minnesota case and by searching public health databases for cases connected to the event. Researchers found that this convention was not a superspreader for Omicron, despite what many feared; safety measures at the event likely played a role in preventing transmission, as did the convention’s timing at the very beginning of NYC’s Omicron wave. I covered the new findings for Science News.

- Americans with lower socioeconomic status have more COVID-19 risk, new paper shows. Researchers at Brookings used large public databases to investigate the relationship between socioeconomic status and the risk of COVID-19 infections or death from the disease. Their paper, published this month in The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, found that education and income are major drivers of COVID-19 risk, as are race and ethnicity. The researchers also found that: “ socioeconomic status is not related to preventative behavior like mask use but is related to occupation-related exposure, which puts lower-socioeconomic-status households at risk.”

- The federal government has failed to disclose how much taxpayers are spending for “free” COVID-19 tests. One month into the Biden administration’s distribution of free at-home COVID-19 tests to Americans who request them, millions have received those tests. But the government has not shared how much it spent for the tests, making it difficult for journalists and researchers to determine how much taxpayer money was paid for each testing kit. “The reluctance to share pricing details flies against basic notions of cost control and accountability,” writes KHN reporter Christine Spolar in an article about this issue. The government has also failed to share details about who requested these free tests or when they were delivered, making it difficult to evaluate how equitable this distribution has been.

Note: this title and format are inspired by Rob Meyer’s Weekly Planet newsletter.

-

Sources and updates, December 5

- State approaches to contact tracing: This report from the National Academy for State Health Policy, updated on December 2, explores how every U.S. state is approaching contact tracing for COVID-19 cases. The report includes state partnerships with research institutions, adjustments for case surges, workforce sizes and training, digital contact tracing apps, and more. (H/t Al Tompkins’ COVID-19 newsletter.)

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor (December update): The newest polling report from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor project is out this week, detailing public opinion on vaccinations, including booster shots, mandates, and more. Two notable findings: four in ten Republican adults are unvaccinated, and Republicans are less likely to report receiving a booster dose than Democrats.

-

A dispatch from Provincetown, Mass.

Provincetown in June 2006. Source: ingawh via Wikimedia Commons Last week, a COVID-19 outbreak in Cape Code, Massachusetts was revealed to be the subject of a major CDC study providing evidence of the Delta variant’s ability to spread through vaccinated individuals. The outbreak quickly became the subject of national headlines, many of them sensationalizing Delta’s breakthrough potential—while failing to provide much context on the people who actually got sick.

Here’s one big piece of context. Provincetown, the center of this outbreak, is one of America’s best-known gay communities, and the outbreak took place during Bear Week. Bear Week, for the uninitiated, is a week of parties for gay, bisexual, and otherwise men-loving men who identify as bears—a slang term implying a more masculine appearance, often facial and body hair.

This week, I had the opportunity to talk to Mike, a Bear Week attendee from Pittsburgh who caught COVID-19 in Provincetown. (Mike asked me to use only his first name to protect his privacy.) He told me about his experience attending parties, getting sick, and learning about the scale of the outbreak.

We also discussed how Provincetown and the Bear Week community were uniquely poised to identify this outbreak, thanks to a better-than-average local public health department and a group of men who were willing to share their health information with officials.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: My first question is just like, how are you doing? How have you been after being involved in this outbreak?

Mike: I’m good… I live in Pittsburgh, I drove back on that Saturday [after the week of Provincetown events] and on Sunday, I started coughing really bad as I was driving home. This just came out of nowhere. I had to pull over, I’m like, yeah, I’m not good. This cough was a lot worse than I had anticipated. So, that was my first symptom. I went into the office Monday after getting home… My first test was negative, on like Monday or Tuesday. But like, I’m still coughing. I didn’t fully trust it. So I got another one Friday, a PCR test.

BL: So, you got tested twice? Did you experience contact tracing, or how did you get identified as part of the outbreak?

M: I mean, I just knew I’d been there. Um, no one reached out but… There was a Facebook group, probably ten or fifteen thousand people in it. Lots of people posted about their test results. Like, people after they were leaving [Provincetown], started quarantining.

The thing about Provincetown is, there were events that happened in the first week [of July, for July 4] that no one really had time to process… Then Bear Week, the week I went, I went at the busiest week of the year for the town. And it had to be, from a planning perspective, I don’t know that was necessarily the best time to have two huge events back to back.

All the official events for the week that I went were canceled, though there were some of the regular bars and stuff doing events. There was, at the time, I think one venue that has a mostly outdoor party every day from like three to seven, that was very heavily attended with one or two thousand people every day, mostly outside and it’s possible to distance at. I only ended up going once or twice just because it wasn’t really where I wanted to be regardless of COVID risks, it wasn’t particularly a scene that I was craving at the time.

I only went to, maybe, three or four indoor things the whole time, and it was without a mask for two or three of them. There’s a bunch of nightclubs in Provincetown that were still having events. And I don’t think that any of the bars themselves that were having events were requiring vaccination cards or anything. One venue that I saw a show at, they announced the next day that they were making either masks or proof of vaccination required. One of the venues that has outdoor events, they just moved all their shows outside instead of inside.

BL: I see. And you mentioned the Facebook group, was that how you found out that a lot of people were getting tested and things like that?

M: Yeah, there were somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand people in the group, planning this whole week. People usually come to Provincetown from all over, sometimes from abroad, though I don’t think there were many people coming from abroad this year because of the restrictions.

BL: How did you learn about the big CDC study getting written about this?

ML: I didn’t really have any idea until afterwards. There were lots of people in the group saying that Barnstable County, or the Massachusetts Department of Health, wanted to know—they wanted people to call if they’d gotten a positive test so they could keep better track of it. I mean, I think part of why the report was able to happen was that it was in a place with better respect for public health than, like, the state of Florida would have, if this kind of outbreak would’ve happened there.

B: Yeah, I mean, it definitely seems like they responded quickly. Because I know they had, like, a 15% positivity rate one week, and then within a pretty short time it was back down.

M: The town itself is a mostly gay, retirement-somewhat community. They can spend lots of money on other things [like public health]. They’re not necessarily spending money on schools because of how many people don’t have any kids around that they need to spend money on. And I mean, there are a lot of residents who live there year-round who tend to be older and are at more risk.

So the week [Bear Week] itself is unique, and then there was a huge community presence about it, everyone wanted to be—for the most part, we’re comfortable about reporting afterwards. I don’t think anyone knew, walking into this, what it would lead to, but… there’s a feeling of community, and that ten thousand-ish Facebook group, I don’t think we otherwise would have necessary talked to each other or told each other about Massachusetts [public health department] asking people to call if they were positive.

BL: And did you do that? Did you call them?

M: Um, I personally didn’t, since I didn’t even find out I was positive until a few days later.

BL: Now, as you know, this outbreak has gotten a lot of national coverage, it’s been kind of sensationalized, with a lot of people focusing on the vaccine breakthrough cases and stuff like that. I know you were not personally one of the people whose test measurements are included there. But what is that experience like of being part of this thing that has gotten so much national attention?

M: I posted about it on social media and there were lots of people who were surprised or whatnot. I think, at least in my head, I went in with a calculated risk, of like 10, 20, 30, or more in the ten thousand-ish people coming, a lot of them are traveling on planes. I drove, thinking I’ll come into this place and I think I’ll make okay decisions…

And there were people in this one place for a whole week, that I guess you were able to test from the CDC’s perspective. I don’t think there are many other places that are as remote as Provincetown where people are staying for the entire week, and everyone generally leaves on the same day, and everyone was in conversation with one another, talking about what happened.

Related links

- I Was Part of the July Fourth Provincetown “Breakthrough” COVID Cluster. It’s Been a Sobering Experience. (Slate)

- How A Gay Community Helped The CDC Spot A COVID Outbreak — And Learn More About Delta (NPR)

- How major media outlets screwed up the vaccine ‘breakthrough’ story (Columbia Journalism Review)

- Latest and greatest on Delta among vaccinated (Your Local Epidemiologist)

-

Video: The future of exposure notifications

Discussing my exposure notifications reporting at the webinar! This week, I had the opportunity to participate in a webinar about the future of exposure notifications, the digital contact tracing systems used in about half of U.S. states. The webinar was hosted by PathCheck Foundation, a global nonprofit that works on public health technology—including exposure notification apps.

I talked about my recent feature in MIT Technology Review, which investigated usage rates and public opinion around exposure notification technology. Other panelists included Jeremy Hall, project manager of Hawaii’s exposure notification system, Sam Zimmerman, director of exposure notification programs at PathCheck, and Ramesh Raskar, technology professor at MIT and PathCheck founder.

It was a great session, with discussion ranging from the challenges of implementing exposure notification technology in the U.S. to the ways this technology may be used for future infectious disease outbreaks. With a year of work under their belts, Zimmerman and Raskar brought insider perspectives to the challenges that I had seen from the outside in my reporting. For example, Raskar discussed how Massachusetts’ own exposure notification app is still in a trial run even though PathCheck approached the state public health agency offering to provide that technology in summer 2020.

I was also excited to hear from Hall on how Hawaii’s public health agency promoted exposure notification technology in their state. At the time I collected data for my Technology Review piece, Hawaii had about 650,000 people in the state’s exposure notification system, including those who downloaded the app and those who turned on the EN Express option in their iPhone settings. That represented 46% of the state’s population—a larger share than any other state.

Since I did my data collection, Hawaii has added an additional 250,000 users, I learned from Hall. This includes both Hawaii residents and tourists; tourists with iPhones get push notifications encouraging them to opt into EN Express when they enter the state. Hawaii has also worked with county public health departments and local organizations to publicize its exposure notification system. I think the state could be a model for other public health institutions working to implement exposure notification technology.

If you’d like to watch the webinar, it was recorded and is available at this link—you’ll just need to put in a name and email. The conversation starts about one minute in.

More on contact tracing

- We need better contact tracing dataThe majority of states do not collect or report detailed information on how their residents became infected with COVID-19. This type of information would come from contact tracing, in which public health workers call up COVID-19 patients to ask about their activities and close contacts. Contact tracing has been notoriously lacking in the U.S. due to limited resources and cultural pushback.

- We need better contact tracing data

-

Evaluating exposure notification apps: Expanded methodology behind the story

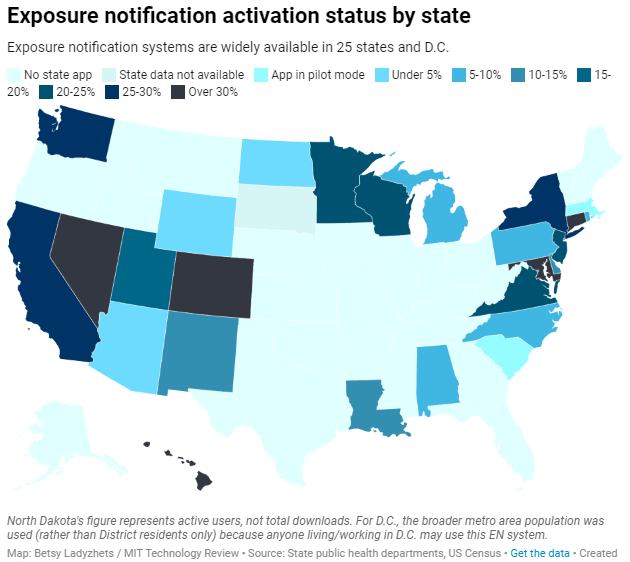

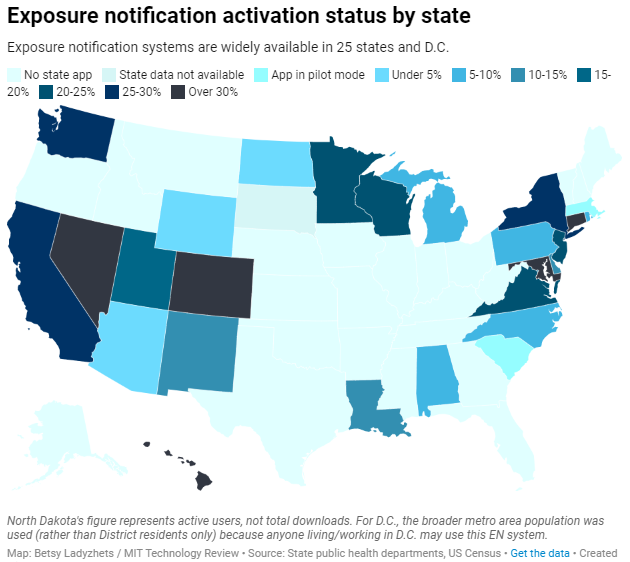

Exposure notification systems are availalbe in 25 states and D.C. This week, I have a new feature out in MIT Technology Review. It’s an investigation into the usage rates and public opinion of exposure notification apps—those Bluetooth-enabled systems that promised to function as a method of digital contact tracing. You can read the story here; and for the CDD this week, I wanted to provide kind-of an extended methodology behind the piece.

The inspiration for this feature came from my conversation with Jenny Wanger, which was published in the CDD back in March. Wanger is the Director of Programs at Linux Foundation of Public Health, a software development network that has worked on exposure notification systems. We discussed the privacy-first design of this technology, as well as how difficult it has been to evaluate how well the apps are working.

That conversation got me thinking: someone should actually try to collect comprehensive data on how many Americans are using exposure notifications. The federal government doesn’t provide any data on this topic, and most of the states that have exposure notification systems available don’t publicly report data, either. But, I thought, there might be other ways to gather some estimates.

When I talked to Lindsay Muscato, an editor at Technology Review’s Pandemic Technology Project (and a longtime CDD reader!), a few weeks later, she agreed that such an investigation would be valuable. The Pandemic Technology Project has done a lot of reporting on exposure notification apps, but hadn’t yet pursued the kind of novel data collection project I was envisioning.

The project started with a hypothesis: that exposure notification systems are underutilized in the U.S. due to a lack of trust in governments and in new technology.

Initially, I planned to use app reviews from the Google Play and Apple stores as the main data source for the story. The two online stores provide download estimates, which I intended to use as a proxy for app usage rates—along with ratings and reviews that I could use as a proxy for public opinion. (Shout-out to machine learning engineer Venelin Valkov, who has put together a great tutorial on scraping and analyzing app store reviews with Python.)

But an interview early in the reporting process caused me to change my data collection plans. I talked to two exposure notification experts at the New Jersey public health agency, who told me that the app download count I saw on the state’s COVID-19 dashboard was actually a significant underrepresentation of the state residents who had exposure notifications enabled on their smartphones.

This data disconnect was due to something called Exposure Notification Express, or ENX. ENX is an upgrade to the digital contact tracing system, released by Apple and Google last September, that made it easier for states to develop new apps. The upgrade also built exposure notifications directly into the iPhone operating system, allowing millions of people to opt into the notifications without downloading a new app.

In short, I couldn’t use app downloads as a proxy for usage rates. I also couldn’t use Apple app store reviews, because the majority of iPhone users were using ENX rather than downloading a new app. Many state apps are listed on the Google Play store but not on the Apple store, for this reason.

I still used Google Play reviews for the public opinion piece of my story. But to determine usage rates, I developed a new plan: reach out to every state public health agency with an exposure notification system and ask for their opt-in numbers. This involved a lot of calling and emailing, including multiple rounds of follow-up for some states.

The vast majority of state public health agencies to whom I reached out did actually get back to me. (Which I appreciate, considering how busy these agencies are!) The only one that didn’t respond was South Dakota; I assumed this state likely had a low number of residents opted into exposure notifications because South Dakota shares an app with two other low-activation states, North Dakota and Wyoming.

Based on my compilation of state data, 13 states have over 15% of their populations opted into exposure notifications as of early May—passing a benchmark that modeling studies suggest can have an impact on a community’s case numbers.

(I used the U.S. Census 2019 Population Estimates to calculate these opt-in rates. I chose to base these rates on overall population numbers, not numbers of adults or smartphone users, because that 15% benchmark I mentioned refers to the overall population.)

This is a smaller number than the engineers who developed this technology may have hoped for. But it does mean these 13 states—representing about one-third of the U.S. population in total—are seeing some degree of case mitigation thanks to exposure notifications. Not bad, for an all-new technology.

I was also impressed by the five states that reported over 30% of their populations had opted into the notifications: Hawaii, Connecticut, Maryland, Colorado, and Nevada. Hawaii had the highest rate by far at about 46%.

For anyone who would like to build on my work, I’m happy to share the underlying data that I collected from state public health agencies. It’s important to note, however, that the comparisons I’m making here are imperfect. Here’s a paragraph from the story that I’d like to highlight:

Comparing states isn’t perfect, though, because there are no federal standards guiding how states collect or report the data—and some may make very different choices to others. For example, while DC reports an “exposure notification opt-in” number on its Reopening Metrics page, this number is actually higher than its residential population. A representative of DC Health explained that the opt-in number includes tourists and people who work in DC, even if they reside elsewhere. For our purposes, we looked at DC’s activation rate as a share of the surrounding metropolitan area’s population (including parts of nearby Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia).

So, did my research support my hypothesis, that exposure notification systems are underutilized in the U.S. due to a lack of trust? Somewhat. I definitely found that the technology has failed to live up to its potential, and the app reviews that I read indicated that many Americans did not trust the technology—or simply failed to understand its role in COVID-19 prevention.

At the same time, however, I found that some states have seen significant shares of their populations opting into the new technology. Plus, the app reviews showed that a lot of people not only trusted the technology—they bought in enough to advocate for it. The majority of states actually had more five-star ratings than any other category, and a lot of those reviewers tried to combat the mistrust they saw elsewhere in the comment section with explanations and endorsements. This is a job that should’ve been done by public health agencies themselves, of course, but the positive reviews may indicate a promising future for this technology.

In the story’s conclusion, I argue that exposure notification technology is still in its trial run here in the U.S. State public health agencies had limited budgets, limited resources, and limited capacity for trust-building. As a result, they focused simply on getting as many people to opt into the technology as possible—rather than any kind of comprehensive data collection or analysis.

“The ultimate goal [of exposure notifications] is for more folks to know they’ve been exposed,” says Hanna Sherrill, an Eagleton Science and Politics Fellow at Rutgers University who worked with the New Jersey public health agency on its exposure notifications system. “Hopefully some of them will take the advice to quarantine, and then they will stop the spread from there. Even if there’s one or two people who do that, that’s a good thing from our perspective.”

Other state public health staffers who responded to Technology Review’s data requests echoed her sentiment—and their attitudes suggest that digital contact tracing in the US may still be in its trial run. We have 26 different prototypes, tested in 26 different communities, and we’re still trying to understand the results.

“In the US, the existing apps and tools have never hit the level of adoption necessary for them to be useful,” Sabeti says. But such success may not be out of reach for future public health crises.

I’m hopeful that, with more investment into this technology, public health agencies can build on the prototypes and develop community trust—before we see another pandemic.

I plan to keep reporting on this topic (including investigation into Google and Apple’s role in the technology, which a couple of readers have pointed out was lacking in the Technology Review piece). If you have further questions or story ideas, don’t hesitate to reach out.

More on contact tracing

- We need better contact tracing dataThe majority of states do not collect or report detailed information on how their residents became infected with COVID-19. This type of information would come from contact tracing, in which public health workers call up COVID-19 patients to ask about their activities and close contacts. Contact tracing has been notoriously lacking in the U.S. due to limited resources and cultural pushback.

- We need better contact tracing data

-

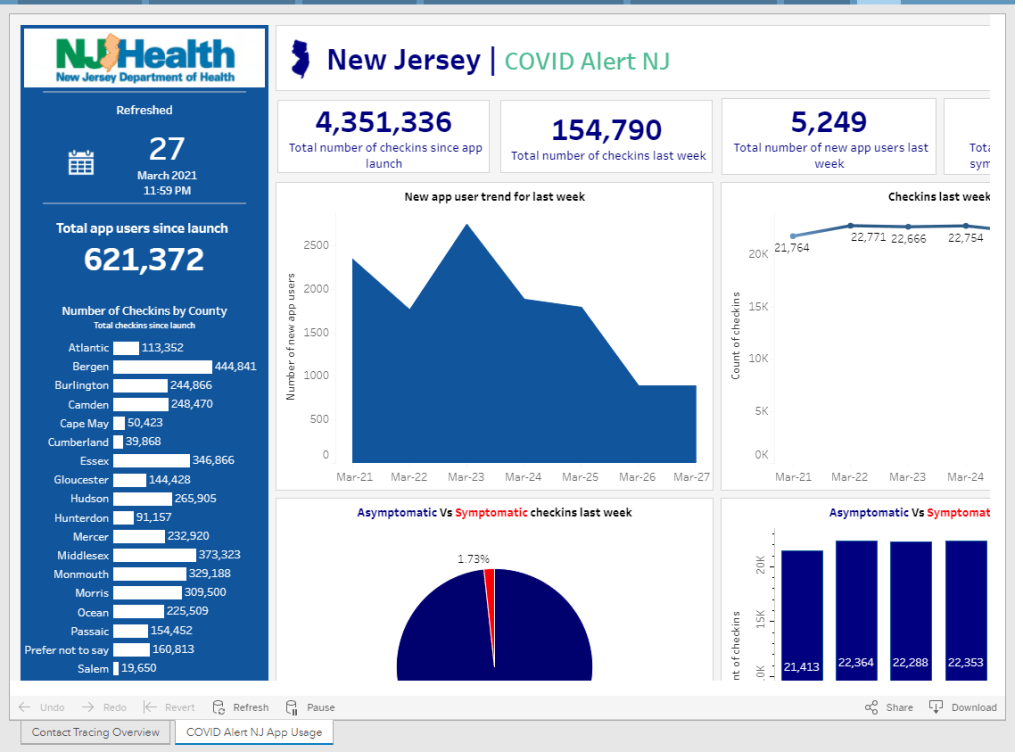

Privacy-first from the start: The backstory behind your exposure notification app

New Jersey reports data on how people are using the state exposure notification app, COVID Alert NJ. Screenshot taken on March 28. Since last fall, I’ve been fascinated by exposure notification apps. These phone applications use Bluetooth to track people’s close contacts and inform them when a contact has tested positive for COVID-19. As I wrote back in October, though, data on the apps are few and far between, leaving me with a lot of questions about how many people actually have these apps on their phones—and how well they’re working at preventing COVID-19 spread.

This week, I put those questions to Jenny Wanger, co-founder of the TCN Coalition and Director of Programs at the Linux Foundation of Public Health. TCN stands for Temporary Contact Numbers, a privacy-first contact tracing protocol developed by an international group of developers and public health experts. As a product manager, Wanger was instrumental in initial collaboration between developers in the U.S. and Europe, and now helps more U.S. states and countries bring exposure notification apps to their populations.

Wanger originally joined the team as what she thought would be a two-week break between her pandemic-driven layoff and a search for new jobs. Now, as the TCN Coalition approaches its one-year anniversary, exposure notification apps are live on 150 million phones worldwide. While data are still scarce for the U.S., research from other countries has shown how effective these apps may be in stopping transmission.

My conversation with Wanger ranged from the privacy-first design of these apps, to how some countries encouraged their use, to how this project has differed from other apps she’s worked on.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: To start off, could you give me some background on how you got involved with the TCN colatition and what led you to this role you’re in now?

Jenny Wanger: My previous company did a very large round of layoffs with the beginning of the pandemic because the economics changed quite dramatically, and I was caught in that crossfire. And a couple of days later, a friend reached out and asked whether I was available to help—he was like, “I need a product manager for this thing, we’re trying to launch these apps for the pandemic. It should be, like, two weeks, and then you can go back to whatever.” So I signed up for that. I thought, sure, I’m not gonna be getting a job in the next two weeks.

A lot of what we were trying to do, the person who brought me on, was to convince people to use the same system and be interoperable with each other, to have more collaboration across projects. As opposed to all of these different apps being built, none of which would be able to work with each other. We found that there was somebody doing the same thing over on the European side, which was Andreas [Gebhard].

We scheduled a meeting with all of the people we were trying to convince to do something interoperable and all of their people, and out of that meeting came the TCN Coalition. Andreas suggested the name TCN Coalition pretty much on a whim, which we’ve learned, never try to name a project in a meeting with other people there, because it will haunt you for a long time.

That’s what we ended up with… TCN Coalition was formed, and we started trying to get everybody to build an interoperable standard and protocol and share that kind-of thing together. It was probably a week or two later that Apple and Google announced that they were going to be having APIs available to use. We weren’t totally sure what to do with that, so we kept moving forward, waiting for more information from them, and then also coaching everybody, like let’s make this interoperable with Apple and Google, that fixes a lot of problems that we weren’t able to fix otherwise.

We kept growing, we started building out some relationships with public health authorities. And meanwhile, somebody started poking around in our area from the Linux Foundation… Eventually, it became clear that we were not gonna be able to grow to the degree that we wanted without a business model, and Linux Foundation brought that piece of the puzzle. So we merged our community to seed the Linux Foundation Public Health, and Linux Foundation Public Health brought in a business model and some funding that allowed us to keep doing the work that we were doing. We were also getting to the point where a bunch of our volunteers were saying that they needed to go back to having jobs… There was a lot of early momentum, and that slowed down over time, understandably.

So yeah, that’s how TCN ended up merging in with LFPH. That man who was poking around TCN way back at the beginning was a guy—his name is Dan Kohn, he unfortunately passed away from cancer at the beginning of November. With that, I ended up taking on more of a leadership role in LFPH than I’d anticipated. We eventually got a new executive director at this point, and I’ve been part of the leadership team throughout. That’s sort-of the high level story.

BL: Thank you. So, how did your background—you do product management stuff, right, how did that lead into connecting coders and running this coalition?

JW: As a product manager, I’ve always been focused on how to get something built that actually meets the needs of a certain population, and is actually useful. There’s two sides to that. One is the project management side, of like, okay, we need to get this done.

But much more relevant has been, on the product side, we need to make sure that we’re building things that—there are so many different players in the space, with an exposure notification app or now as we’re looking at vaccine credentials. You’ve got the public health authority, who is trying to achieve public health goals. You’ve got the end user, who actually is going to have this product running on their phone. You have Apple and Google, or anybody else who is controlling the app stores, that have their own needs. You’ve got the companies that are actually building these tools out, building out these products who are trying to hit their own goals. It’s a lot of different players, and I think where my background as a product manager has really helped has been, I’ve got frameworks and tools of how to balance all these different needs, figure out how to move things forward and get people working together, get them on the same page, to actually have something go to market that does what we think it’s supposed to do.

BL: Right. To talk about the product itself now, can you explain how an exposure notification app works? Like, how would you explain it to someone who’s not very tech savvy.

JW: The way I explain exposure notification is essentially that your phone uses Bluetooth to detect whether other phones are nearby. They do this by broadcasting random numbers, and the other phones listen for these random numbers and write them down in a database.

That’s really all that’s happening—your phone shouts out random numbers, they’re random so that they don’t track you in any way, shape, or form, they’re privacy-preserving. You’ve got that cryptographic security to it. The other phones write down the numbers, and they can’t even tell, when they get two numbers, whether they’re from the same phone or different phones. They just know, okay, if I received a number, if I wrote it down, that means I was close enough to that phone in order to be at a distance, being at risk of COVID exposure.

Then, let’s say one of those phones that you were near, the owner of that phone tests positive. They report to a central database, “Hey, I tested positive.” When this happens, all of the random numbers that that phone was broadcasting get uploaded to a central server. And what all the other phones do is, they take a look at the list on the central server of positive numbers, and they compare it to the list that’s local on their phone. If there’s a match, they look to see, like, “How long was I in the vicinity of this phone? Was it for two minutes, five minutes, 30 minutes?”

If it goes over the threshold of being near somebody who tested positive for enough time that you’re considered a close contact, then you get a notification on your phone saying, “Hey, you were exposed to COVID-19, please follow these next steps.”

The nice thing about this system is, it’s totally privacy-preserving, there’s pretty much no way for anybody to look at these random numbers and tell who’s tested positive or who hasn’t. They can’t tell who anybody else has been by. So it’s a really privacy-first system.

And what we’re now seeing, which is really exciting, is that it’s effective. There’s a great study that just came out of the U.K. about a month ago, showing that for every additional one percent of the population that downloaded the NHS’s COVID-19 app, they saw a reduction in cases of somewhere between 0.8 and 2.3 percent.

BL: Oh, wow.

JW: The more people that adopt the app, it actually has had a material impact on their COVID-19 cases. The estimates overall are as many as 600,000 cases were averted in the U.K. because of this app.

Editor’s note: The study, by researchers at the Alan Turing Institute, was submitted for peer review in February 2021. Read more about the research here.

BL: That goes into something else I was going to ask you, which is this kind-of interesting dynamic between all the code behind the apps being open source, that being very public and accessible, as opposed to the data itself being very anonymized and private—it’s this tradeoff between the public health needs, of we want to use the app and know how well it’s working, versus the privacy concerns.

JW: The decision was made from the beginning, since the models showed higher levels of adoption of these apps was going to be critical in order for them to be successful. The more people you could get opting into it, the better. Because of that, the decision was made to try and design for the lowest common denominator, as it were. To make sure that you’re designing these apps to be as acceptable to as many people as possible, to be as unobjectionable as possible in order to maximize adoption.

With all of that came the privacy-first design. Yes, a lot of people don’t care about the privacy issues, but we were seeing that enough people cared about it that, if we were to launch something that compromised somebody’s privacy, we were going to see blowback in the media and we were going to see all sorts of other issues that tanked the success of the product.

Yes, it would be nice to get as much useful information to public health authorities as possible, but the goal of this was not to supplant contact tracing, but to supplement it. The public health authorities were going to be getting most of the data that we were able to provide via they know who’s tested positive. They’re already getting contact tracing interviews with them. It wasn’t clear what we could deliver to the public health authority system that wasn’t already being gathered some other way.

There could’ve been something [another version of the app] where it gave the exposure information, like who you’ve been with, to the public health authority, and allowed them to go and contact those people before the case investigations did. But there were so many additional complications to that beyond just the privacy ones, and that wasn’t what—we weren’t hearing that from the public health authorities. That wasn’t what they needed. They were trying to figure out ways to get people to change behavior.

We really pressed forward with this as a behavior change tool, and to get people into the contact tracing system. We never wanted it to replace the contact tracing that the public health authorities were already spinning up.

BL: I suppose a counter-argument to that, almost, is that in the U.S., contact tracing has been so bad. You have districts that aren’t able to hire the people they need, or you have people who are so concerned with their privacy that they won’t answer the phone from a government official, or what-have-you. Have you seen places where this system is operating in place of contact tracing? Or are there significant differences in how it works in U.S. states as opposed to in the U.K., where their public health system is more standardized.

JW: Obviously, none of us foresaw the degree to which contact tracing was going to be a challenge in the U.S. I think, though, it’s very hard—the degree to which we would’ve had to compromise privacy in order to supplant contact tracing would have been enormous. It’s not like, oh, we could loosen things just a little bit and then it would be a completely useful system. It would have to have been a completely centralized, surveillance-driven system that gave up people’s social graphs to government agencies.

We weren’t designing this, at any point in time, to be exclusively a U.S. program. The goal was to be a global program that any government could use in order to supplement their contact tracing system. And so we didn’t want to build anything that would advance the agenda—we had to think about bad actors from the very beginning. There are plenty of people just in the U.S. who would use these data in a negative way, and we didn’t want to open that can of worms. And if you look at more authoritarian or repressive governments, we didn’t want to allow them a system that we would regret having launched later.

BL: Yeah. Have you seen differences in how European countries have been using it, as compared to the U.S.?

JW: There have been some ways in which it’s been different, which has more to do with attitudes of the citizenry than with government use of the app itself. The NHS [in the U.K.] has a more unique approach.

The U.K. and New Zealand both ended up building out a QR code check-in system, where if you go to a restaurant or a bar… You have a choice, either you write your name and phone number in a ledger that the venue keeps at their front door. So if there’s an outbreak later, they can call you, reach out and do the case investigation. Or you scan a QR code on your phone that allows you to check into that location and figure out where you’re moving. If there’s an alert [of an outbreak] there, you get a notification saying, you were somewhere that saw an outbreak, here’s your next steps.

One of the big advantages of the U.K. choosing to do that is essentially that—every business had to print out a QR code to post at their front door. Something like 800,000 businesses across England and Wales printed out these QR codes. And that means anyone who walks into one of those venues gets an advertisement for their app, every single time they go out. It was very effective in getting good adoption.

We’ve also seen a very big difference in how different populations think about the app and use it. For instance, Finland has had very good compliance with their app. What we mean by that is, if you test positive and you get a code that you need to upload, in Finland, there’s a very high likelihood that you actually go through that process in your exposure notification app. That’s something that I think a lot of jurisdictions have been struggling with in the U.S. and other countries—once you get the code, making sure that somebody actually uploads it.

It makes sense, because getting a positive diagnosis for COVID is a very stressful thing. It’s a very intense moment in your life. And you might not be thinking immediately, “Oh, I should open my app and upload my code!”

BL: Right, that’s not the first thing you think of… This relates to another question I have, which is how you’ve seen either U.S. states or other countries adapting the technology for their needs. You talked about the U.K. and New Zealand, but I’m wondering if there are other examples of specific location changes that have been made.

JW: There have been some mild differences. Like, this app will allow you to see data about how each county is performing in your jurisdiction, so you can also go there to get your COVID dashboard. I’ve seen some apps where, if you get a positive exposure notification, that jumps you to the front of a line for a test. You can schedule a test in the app and you can get a free test as opposed to having to pay for it.

I’ve seen things like that, but overall, at least with the Google/Apple exposure notification system, it’s been small changes to that degree. Where you see more dramatic changes is where countries have built their own system. You can look at something like Singapore, where people who don’t have phones get a dongle that they can use to participate in the system. It’s entirely centralized, and so they are able to do things like, a lot of contact tracing actually from the information they get with the app. There are places where it’s more aggressive in that sense.

For the most part, though, I’d say it’s been pretty consistent… The one-year anniversary of the TCN Coalition isn’t until April 5, but if you think about how far we’ve come from this just being an idea in a couple of people’s heads to, last I heard, the GAIN [Google/Apple] exposure notification apps are on 150 million phones worldwide.

BW: Wow! Is that data publicly available, on say, how many people in a certain country have downloaded apps? I know, one state that I’ve found is publishing their data is New Jersey, they have a contact tracing pane on their dashboard. I was curious if you’d seen that, if you have any thoughts on it, or if there are any other states or countries that are doing something similar.

JW: I wish there was more transparency. Switzerland has a great dashboard on the downloads and utilization of their app. DC, Washington state, also publicly track their downloads. I’m sure a few others do but I don’t know off the top of my head who makes the data public.

I do wish it were the default for everybody to make that data public… There’s a lot of concern by states where there’s not good adoption, that by making the data public they’re opening up a can of worms and are going to get negative press and attention for it, so they don’t want to. So it’s been a mix in that way.

BL: I think part of that is also an equity concern. How do you know that you have a good distribution of the population that’s adopting it, or even that the people who need these apps the most, say essential workers, people of color, low-income communities—how do you know that they’re adopting it when it’s all anonymous?

JW: It’s actually—if you’re going to have low adoption, what’s much more effective is if you have high adoption in a certain community. There is a health equity question, but it’s not necessarily about equal distribution of the app, but rather—and this is where some states have been successful, is that they haven’t gotten high adoption across the board but they’ve decided on a couple of high-need communities that are the ones they’re going to target for getting adoption of the app. They’ve gone after those instead, and that, for many of the states, has been a more effective way to drive use.

BL: I live in New York City, and I know I’ve seen ads for the New York one, like, in the subways and that sort of thing, which I have appreciated.

Is there a specific state or country that you’d consider a particularly successful example of using these apps?

JW: NHS, England and Wales, definitely. I think Ireland has done a pretty good job of it, and Ireland is—we’re particularly fond of them because they were one of the first to open source their code, and make it available. They open-sourced with LFPH to make it available for other countries, and so that is the code that powers the New York app as well. New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and then a couple of other countries globally, including New Zealand. It’s the most used code, besides the exposure notification express system that Apple and Google built for getting these apps out.

I also mentioned Finland before, I think they got the messaging right such that they have very high buy-in on their app.

BL: Are you collecting user feedback, or do you know if various states and countries are doing this, in order to improve the apps as they go?

JW: Usually as a product manager, you’re constantly wanting to improve the UI [user experience] of your app, getting people to open it, and all that. These are interesting apps in that they’re pretty passive. Your only goal is to get people not to delete them. They can run in the background for all of eternity. As long as the phone is on and active, that’s all that’s needed.

BL: As long as you have your Bluetooth turned on, right?

JW: As long as you have your Bluetooth turned on. So the standard for the success of these apps is a completely different beast. We at LFPH have not been monitoring the user feedback on this, but a lot of states and countries are. Most of them have call centers to deal with questions about the app.

Some jurisdictions are improving it, but most improvements are focused on the risk score, which is the settings about how sensitive the app should be.

BL: Like how far apart you need to be standing, or for how long?

JW: Right. How to translate the Bluetooth signal into an estimate of distance, and how likely should it be—how willing are you to send an alert to somebody, telling them that they’ve been exposed, based on your level of confidence about whether they actually were near somebody or not. There’s a decent amount of variance there in terms of how a state thinks about that, but that’s been much more on the technical side, where people are trying to tweak the system, than on the actual app. There have been some language updates to clarify things, to make it easier for people to know what to do next, but it’s not been the core focus of the app designs like it would be if this were a more traditional system.

BL: What does your day-to-day job actually look like, coordinating all of these different systems?

JW: We’re [LFPH/TCN] really an advisor to the jurisdictions. It’s not a coordinating thing but rather, I spend a lot of my time on calls with various states saying, “Here’s what’s happening with the app over in this place, here’s what this person is doing, have you considered this, do you want to talk to that person.” I’m trying to connect people, trying to provide education about how these systems work, and for the states that are still trying to figure out whether to launch or not, convincing them to do it and sharing best practices.

Also, with Linux Foundation Public Health, we’re working on a vaccination credentials project. So I’m splitting my time between those, as well as just running the organization and keeping financials, board relationships, networking, fundraising, keeping all of those things together.

BL: Sounds like a lot of meetings.

JW: It’s a fair number of meetings, this is true.

BL: So, that’s everything I wanted to ask you. Is there anything else you’d like folks to know about the system?

JW: Ultimately, the verdict is, now that we’re seeing it’s effective [from the U.K. study], I think that adds to the impetus to download and use the system. Even before that, though, the verdict was—this is extraordinarily privacy-preserving, there’s no reason not to do it. That continues to be our message. There’s no harm in having this on your phone, it doesn’t take up much battery life, so turn it on!

-

Where are we most likely to catch COVID-19?

This week, I wrote a story for Popular Science that goes over what we know (and don’t know) about the most common settings for COVID-19 infection.

Most of the main points will probably be familiar to CDD readers, but it’s still useful to compile this info in one concise article. Here are the main points: Outside events are always safer. Surfaces are not a common transmission source. Communal living facilities and factories tend to be hotspots. Indoor dining and similar settings carry a lot of risk. Essential workers are called essential for a reason. And don’t rule out small gatherings, even though such events are safer for those of us who’ve been vaccinated.

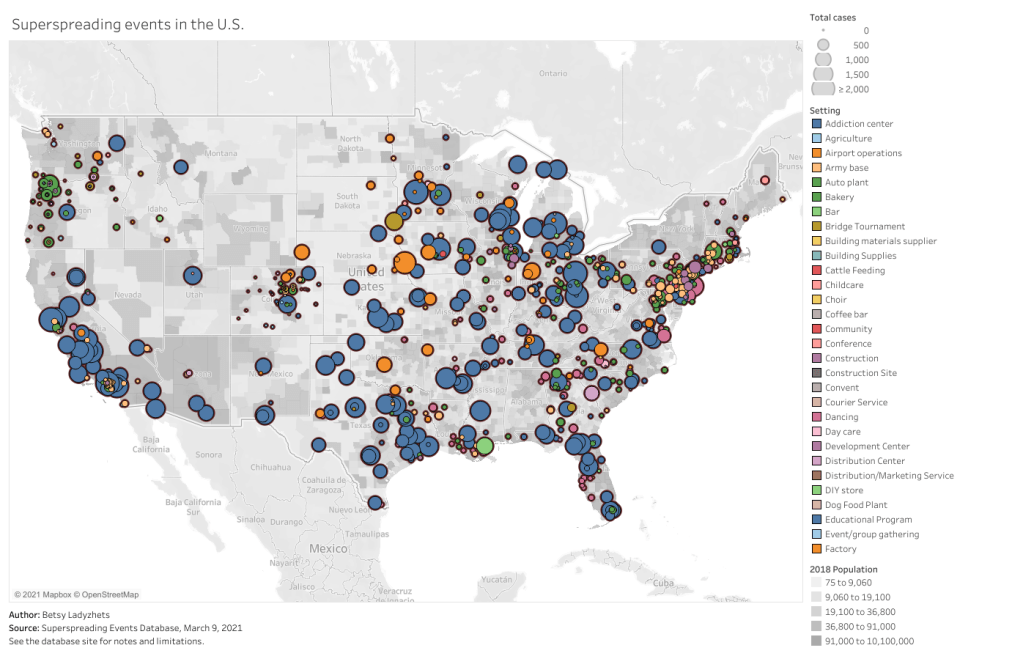

This story gave me an excuse to revisit one of my favorite COVID-19 datasets: the Superspreading Events Database, a project that compiles superspreading events from media reports, scientific papers, and public health dashboards. I interviewed Koen Swinkels, the project’s lead, for the CDD back in November.

At that time, the database had about 1,600 events; now, it includes over 2,000. All of the patterns I wrote about in November still hold true now, though. Notably, no event in the database took place solely outside (though Swinkels told me he’s seen some events with both an indoor and outdoor component). And the vast majority of events in the database took place in the U.S.

For those U.S. events, most common superspreading settings are prisons (166,000 cases), nursing homes (30,000 cases), rehabilitation/medical centers (24,000 cases), and meat processing plants (13,000 cases). By this database’s definition, a superspreading event may comprise a sustained outbreak at one location over a long period of time—and prisons have been continuous hotspots since last spring.

You can check out the U.S. superspreading events in the database below. I made this visualization in November and updated it this past week.

One of the reasons why I like the Superspreading Events Database is that Swinkels and his collaborators are extremely clear on the project’s limitations. If you load the database’s public Google sheet, you’ll see a prominent note at the top reading, “Note that the database is NOT a representative sample of superspreading events. Please read this article for more information about the limitations of the database.” The article, a post on Swinkels’ Medium blog, goes in-depth on the biases associated with the database. It’s easier to identify superspreading events in institutional settings, for example, since many of them employ frequent testing. Still, I think that—when carefully caveated—this database is an incredibly useful resource for identifying patterns in COVID-19 spread.

Swinkels additionally pointed me to another great source for exposure data: the state of Colorado publishes outbreak data in weekly reports. A few other states publish similar info, but Colorado’s data are highly detailed and complete. In this past week’s report, released on March 10, the state says that 6,900 out of a total 28,000 cases in active outbreaks are linked to state prisons. 3,900 more cases are linked to jails.

I’ve visualized the March 10 Colorado outbreak data below. As you may notice, the next-biggest outbreak setting after prisons and jails is higher education—colleges and universities represent 6,700 active outbreak cases. Colorado’s dataset does not specify how many of those cases are linked to the mask-less University of Colorado party that drew wide criticism last weekend… but we can assume that party was no small player.

Finally, this PopSci story also gave me an excuse to revisit one of my favorite COVID-19 data gripes: the lack of contact tracing info we have in the U.S. I’ve written about this issue in the CDD before; I surveyed state dashboards in October, and drew connections from the Capitol invasion in January. But it was still disheartening to find that now, in March, we continue to be largely in the dark about how many contact tracers are actively employed in most states and how many people they’re reaching.

Here’s a clip from the story:

In the US, though, the practice is done unevenly, if at all. Most states and local jurisdictions, struggling from years of underfunded public health departments leading up to the pandemic, have not been able to hire and train the contact tracers needed to keep tabs on every case.

Many states have attempted to supplement their limited contact tracing workforces with exposure notification apps, which are theoretically able to notify users when they’ve come into contact with someone who tested positive. Though these apps became more widespread in the US this past winter, they’re still not used widely enough to provide useful information. New Jersey, one state that provides data on its app use, reports that about 574,000 state residents have downloaded the app as of March 6—out of a population of 8.9 million.

This situation is not likely to improve much in the coming months as Americans aren’t about to change their perspectives on privacy any time soon. But if you have the opportunity to download an exposure notification app for your state, do it! The more data we have on where people are getting exposed to COVID-19, the better we can understand this virus.

Related posts

- We need better contact tracing dataThe majority of states do not collect or report detailed information on how their residents became infected with COVID-19. This type of information would come from contact tracing, in which public health workers call up COVID-19 patients to ask about their activities and close contacts. Contact tracing has been notoriously lacking in the U.S. due to limited resources and cultural pushback.

- We need better contact tracing data

-

Was the Capitol invasion a superspreader event?

Like everyone else, I spent Wednesday afternoon watching rioters attack the nation’s Capitol. I was horrified by the violence and the ease with which these extremists took over a seat of government, of course, but a couple of hours in, another question arose: did this coup spread COVID-19?

The rioters came to Washington D.C. from across the country. They invaded an indoor space in massive numbers. They pushed legislators, political staff, and many others to hide in small offices for hours. They inspired heated conversations. And, of course, none of them wore masks. These are all perfect conditions for what scientists call a superspreading event—a single gathering that causes a lot of infections.

(The number can vary, based on how you define a superspreading event; for more background, see this post from November.)

My concerns were quickly echoed by many other COVID-19 scientists and journalists:

The very next day, Apoorva Mandavilli published a story asking just this question in the New York Times. She quotes epidemiologists who point out that the event was ripe for superspreading among both rioters and Capitol Hill politicians. Many legislators were stuck together in small rooms, having arguments, while some of the Republican representatives refused to wear masks. POLITICO got a video of several Republicans refusing masks in a crowded safe room.

By Friday, five Congressmembers had tested positive for COVID-19 in a week. It’s true, many of these legislators received vaccines in the first stage of the U.S. rollout in late December. But it takes several weeks for a vaccine to confer immunity, and we still don’t have strong evidence as to whether the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines prevent the coronavirus from spreading to other people. (They likely do, to some extent, but the evidence mainly shows that these vaccines prevent COVID-19 disease.)

Just this morning, Punchbowl News’ Jake Sherman reported that the attending physician for Congress sent a note to all legislators and staff, warning them that “people in the safe room during the riots may have been exposed to the coronavirus.” I will be carefully watching for more reports of legislators testing positive in the coming weeks. From our nation’s previous experience with COVID-19 outbreaks at the White House, it seems unlikely that the federal government will systematically track these cases—though the incoming administration may change this.

As for the rioters themselves, while the events of January 6 may well have been superspreading, we likely will never know the true extent of this day’s impact. As I’ve written previously, we identify superspreading events through contact tracing, the practice of calling up patients to quiz them on their activities and help identify others who may have gotten sick. When case numbers go up—as they are now—it becomes harder to call up every new patient. One county in Michigan is so understaffed right now, it’s telling COVID-19-positive residents to contact trace themselves.

But even if contact tracing were widely available in the communities to which those rioters are going home, can you really imagine them answering a phone call from a public health official? Much less admitting to an act of treason and risking arrest? No, these so-called patriots likely won’t even get tested in the first place.

It would take rigorous scientific study to actually tie the Capitol riot to COVID-19 spread to the homes of the rioters. (That said, if you see a study like that in the months to come: please send it my way.)

Finally, I have to acknowledge one more impact of the riot on D.C. at large: vaccine appointments were canceled after 4 PM that day. One of the most heinous aspects of that riot, to me, was how it pulled our collective attention away from the pandemic, precisely at a time when our collective health needs that attention most.