A few days ago, my partner and I returned home from a two-week vacation to several cities in Europe. It was our first time traveling internationally since before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the trip required a lot of time on planes, on public transportation, and in crowded spaces.

I’m sharing what we did to reduce our risk of COVID-19 (and other common pathogens!) during the trip, in the hope that this will be helpful for readers traveling this summer. While taking these sorts of precautions may be increasingly unpopular in many places, these measures still reduce the risk of illness for individual travelers and the people around them.

Here’s what we did:

- Reduced potential exposure and tested before we traveled: It’s pretty typical for me to avoid crowds and indoor events prior to traveling. In this case, my partner and I did attend Pride marches in New York City the weekend before our trip, but we only attended outdoor events and wore masks in the crowds to reduce our risk. We also both got PCR tests the day before leaving (we’re lucky to live near one of the few public testing sites in the city that are still open).

- Masked indoors, with high-quality masks: I consistently wore N95 masks on the trip, including my reusable respirator on planes. (I wrote more about my respirator in this post last summer.) My partner also wore an N95 or KN95 throughout the trip. We have different preferences for which masks fit us well, so we had a few masks of different brands packed to accommodate that.

- Avoided indoor dining (as much as possible): All of our meals were outdoors. My partner is vegan, so any restaurant where we ate had to fit into a Venn diagram of “vegan options” plus “outdoor seating”; this might sound challenging to find, but with a bit of planning—and with thanks to the Happy Cow app—it was actually quite doable. We had to eat briefly on planes at a couple of points, but we minimized that time as much as possible (eg. masking in between bites) and did so only when plane air filtration systems were going.

- Took advantage of smoking sections: European cities tend to have a more prominent smoking culture than the U.S., so many restaurants and bars have outdoor smoking sections. This can be a tricky situation for COVID-cautious travelers; yes, you’re outside, but you’re also breathing in a lot of second-hand smoke. Still, my partner and I found these sections to be a helpful option. We even had lunch in an outdoor smoking zone at the Keflavik Airport (in Iceland) during a layover on our way home to NYC.

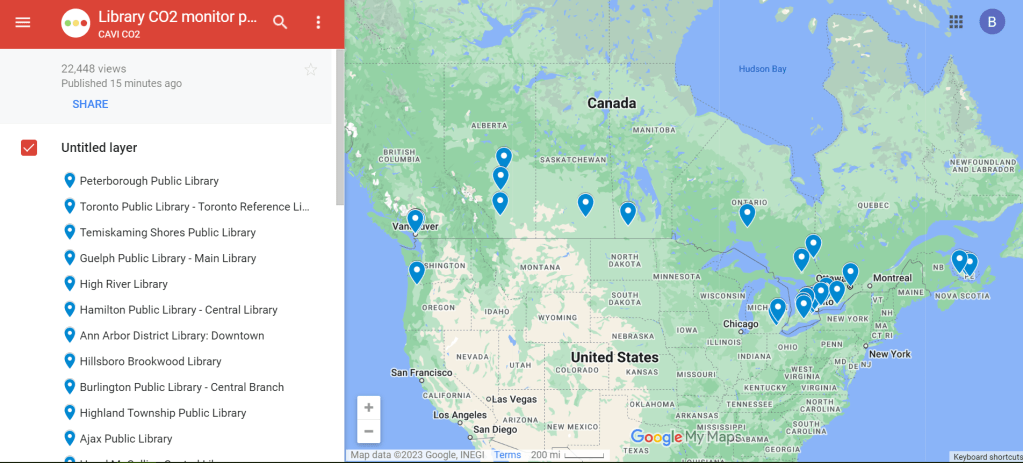

- Used a CO2 monitor to gauge ventilation in some spaces: I am a proud owner of an Aranet CO2 monitor, which I mostly use to track ventilation at my apartment and public spaces in NYC. I brought the monitor on the trip, and used it to identify which public buildings had better air quality. For example, train platforms at Berlin Hauptbahnhof (the city’s central train station) are open to outdoor air and have frequent airflow, as evidenced by a CO2 reading I took of 611 ppm—well within the Aranet monitor’s “green zone.” So, I felt comfortable taking off my mask there for a few minutes to drink coffee.

- Used a HEPA filter on trains, hotel rooms: My partner and I have a personal, portable HEPA filter that runs on a battery and fits easily in my duffel bag. I brought it along on the trip and used it a few times, mostly on crowded trains and in hotel rooms that did not have great airflow. It also doubled as an extra fan in our Airbnb in Amsterdam (which was not air-conditioned).

- Rapid-tested every two days: Over the two weeks of traveling, my partner and I took a rapid test every two days to check for any developing illness. We also requested testing from friends and family members with whom we spent time indoors, such as a friend whom we stayed with in Berlin.

- Testing and symptom monitoring after getting home: Since arriving home in NYC on Wednesday evening, my partner and I have each gotten PCR tests. I also rapid-tested once, as an extra check before attending an event on Thursday. We’re planning to do another round of PCR testing next week and monitor for any symptoms; so far, we haven’t seen any signs of illness.

I acknowledge that these safety measures may sound like a lot of effort. Certainly, tools like rapid tests and a personal HEPA filter cost money, and may not be accessible to many people. And in an ideal world, everyone would be able to travel in a world where these tools are free and commonplace, rather than a reason for extra advanced planning.

There are also increasing social pressures to not take precautions, especially in some of the places that we visited. I had a few conversations with strangers who insisted I was strange for wearing an N95, that COVID-19 was “over”; I was even patted down and pulled into a security screening at the Amsterdam airport by guards who decided my respirator was suspicious.

I am the kind of person who doesn’t back down to this pressure, especially when I have the research and reporting to back up my convictions. But I don’t want to be an isolated person taking precautions in a sea of others who aren’t acting to protect public health.

Broader change is really needed; in the meantime, though, I hope my experience is informative for others.

If you are also traveling this summer and you have other tips you’d like to share with the COVID-19 Data Dispatch community, please send them to me! You can email me or comment on this post.