- CDC updates its variant classifications: This one is more of an update than a new source. On Thursday, the CDC updated the list of coronavirus variants that the agency’s scientists are watching. This list now includes three categories: Variants of Concern (or VOCs, which pose a significant threat to the U.S.), Variants of Interest (which may be concerning, but aren’t yet enough of a threat to be VOCs), and Variants Being Monitored (which were previously concerning, but now are circulating at very low levels in the U.S.). Notably, Delta is now the CDC’s only VOC; all other variants are Variants Being Monitored.

- COVID-19 School Data Hub: Emily Oster, one of the leading (and most controversial) researchers on COVID-19 cases in K-12 schools, has a new schools dashboard. The dashboard currently provides data from the 2020-2021 school year, including schools’ learning modes (in-person, hybrid, virtual) and case counts. Of course, data are only available for about half of states. You can read more about the dashboard in this Substack post from Oster.

- Influenza Encyclopedia, 1918-1919: In today’s National Numbers section, I noted that the U.S. has now reported more deaths from COVID-19 than it did from the Spanish flu. If you’d like to dig more into that past pandemic, you can find statistics, historical documents, photographs, and more from 50 U.S. cities at this online encyclopedia, produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

Category: Variants

-

Featured sources, September 26

-

Our pandemic winter: Stories on what to expect

This week, two of the outlets that I consider to be among the most reliable COVID-19 news sources published stories on our coming pandemic winter. Obviously, you should read both pieces in full, but here are my takeaways.

The first story comes from The Atlantic’s science desk, with a triple-star byline including Katherine J. Wu, Ed Yong, and Sarah Zhang.

This piece focuses on the changing role of vaccination in protecting the U.S. from COVID-19. After a few months of encouraging data, suggesting that vaccines could protect us against coronavirus infection and transmission, we are now back to using COVID-19 vaccines for their initial purpose: preventing severe disease and death. As we see higher numbers of breakthrough cases, we can take comfort in the fact that those cases will rarely lead to hospitalization or death. (Though the risk of Long COVID after vaccination is less known.)

The Atlantic’s article also explains who is now most at risk of COVID-19, and how that risk may shift in the coming months. Right now, unvaccinated children face high risk, especially if they live in communities where most of the adults aren’t vaccinated. But that won’t always be the case:

Relative risk will keep shifting, even if the virus somehow stops mutating and becomes a static threat. (It won’t.) Our immune systems’ memories of the coronavirus, for instance, could wane—possibly over the course of years, if immunization against similar viruses is a guide. People who are currently fully vaccinated may eventually need boosters. Infants who have never encountered the coronavirus will be born into the population, while people with immunity die. Even the vaccinated won’t all look the same: Some, including people who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, might never respond to the shots as well as others.

At the end of the article, the writers touch on variants. Delta is now the world’s major concern, but future variants might develop new mutations and pose new dangers. Yet the writers say that any variant “can be stopped through the combined measures of vaccines, masks, distancing, and other measures that cut the conduits they need to travel.”

The second “pandemic winter” story comes from ace STAT News reporter Helen Branswell. Branswell goes into more detail about potential variant scenarios, outlining what Delta may do and how other mutations may arise as the weather gets colder.

Some modeling efforts suggest that COVID-19 case numbers may stay low once the Delta wave ends, Branswell reports, because the majority of Americans are now fully vaccinated or have some immunity from a prior infection. But if another dangerous variant comes along, we could be in trouble. Still, if cases go up again, we won’t see as many hospitalizations or deaths as we did last winter, thanks to the vaccines.

I personally take comfort in this quotation from computational biologist Trevor Bedford:

“It is likely that we’ll see some wave,” Bedford said. “I would like to think it’s very unlikely to be as big as it was last year.”

Because Delta is causing the vast majority of the world’s COVID-19 cases right now, Branswell reports, future variants would likely arise from Delta. That could mean even more transmissibility or challenges to the human immune system. There’s a lot of uncertainty involved in trying to predict mutations, though. Branswell points out:

Early in the pandemic, coronavirus experts confidently opined that this family of viruses mutates far more slowly than, say, influenza, and major changes weren’t likely to undermine efforts to control SARS-2. But no one alive had watched a new coronavirus cycle its way through hundreds of millions of people before.

Branswell’s story also spends time explaining the potential pressures that COVID-19 could put on the healthcare system if combined with flu or other respiratory viruses. Healthcare workers may need to distinguish COVID-19 cases from flu cases, then treat both with similar equipment.

The story makes a pretty good argument for getting your flu shot now, if it’s available to you. I got mine last week.

-

Delta updates: Disease severity, kids, boosters

The states with the highest numbers of children in the hospital are also the states with the lowest vaccination rates, per CDC analysis. It’s been a minute since I last did a Delta variant update, and this seemed like a good week to check in. Here are a couple of major news items that I’ve seen, along with sources where you can read more.

The Delta variant continues to be highly transmissible. On August 1, I wrote that an interaction of a few seconds is enough for Delta to spread from one person to another, when both people are unvaccinated and unmasked.

All the new evidence that we have on Delta outbreaks backs up its incredible ability to spread. For example, in a California elementary school, an unvaccinated teacher spread the coronavirus to 12 out of the 24 students in her class, with students sitting closer to the teacher more likely to be infected. The classroom outbreak led to 27 cases in total, including the teacher—who worked for two days after first reporting her symptoms. All the cases were identified as Delta.

Growing evidence points to Delta being more severe. A recent study in The Lancet from epidemiologists in the U.K. suggests that Delta causes severe disease more frequently than the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7). The researchers looked at hospitalization rates for British COVID-19 patients, finding that patients with Delta were twice as likely to require hospital care compared to those with Alpha. Delta patients were also younger, on average—though this could be conflated by high vaccination rates among British seniors.

Commenting on this study in Your Local Epidemiologist, Dr. Katelyn Jetelina writes:

This adds to the growing evidence that Delta is more severe. An early Scotland study found that the risk of hospitalization was nearly double than previous variants. An early Public Health of England technical report found this too. We also saw this in Singapore where Delta infection was associated with higher risk of oxygen requirement, ICU admission, or death.

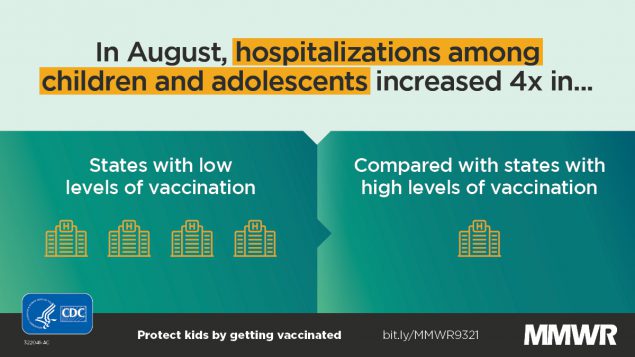

For kids, higher hospitalization rates are tied to community vaccination, not Delta severity. This Friday, the CDC released two reports on COVID-19 hospitalization in children.

One major finding: out of all children with COVID-19 cases, the proportion of kids who have a severe case has not increased from previous surges to this current Delta surge. Prior to June 2021, about 27% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients under age 18 required ICU admission; in late June and July (during the Delta surge), that number was 23%. Also, the average hospital stay was shorter during the Delta surge than previously (1-4 days compared to 2-5 days). These statistics indicate that Delta isn’t more severe for kids—rather, we’re seeing cases in such high numbers that it drives up hospitalizations.

According to the CDC’s other Friday report, hospitalizations among children (under age 18) were four times higher in states with low vaccination levels compared to states with high vaccination levels. In other words: vaccination is crucial not just to protect yourself from severe COVID-19, but to lower community transmission and protect young children who can’t yet be vaccinated.

Evidence for boosters continues to be questionable. After the Biden administration announced that the U.S. plans to provide third vaccine doses to everyone who received Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines, I wrote that evidence and transparency on this decision were lacking. The situation hasn’t changed much; while studies show that COVID-19 antibody levels decline several months after vaccination, many experts are not convinced that boosters are necessary for everyone at this point.

If immunity is “waning,” why don’t we need extra shots? As usual, Katherine Wu at The Atlantic has a great article explaining the complexities here. Here’s a key paragraph from her piece:

Defensive cells study decoy pathogens even as they purge them; the recollections that they form can last for years or decades after an injection. The learned response becomes a reflex, ingrained and automatic, a “robust immune memory” that far outlives the shot itself, Ali Ellebedy, an immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told me. That’s what happens with the COVID-19 vaccines, and Ellebedy and others told me they expect the memory to remain with us for a while yet, staving off severe disease and death from the virus at extraordinary rates.

In short, though antibody levels may drop, that represents just one measurement of the immune system’s ability to fight COVID-19. Other parts of the immune system will remain ready to address the coronavirus for long after an individual is vaccinated—you just might be more likely to have an asymptomatic or mild case, rather than avoiding infection entirely. (One big caveat here: We don’t know much about the risk of Long COVID after vaccination.)

In fact, both Rochelle Walensky (CDC director) and Janet Woodcock (interim head of the FDA) are reportedly “pushing back on the White House’s plan” for booster shots, saying they need more time to collect and review data. I, for one, hope all of their data — and discussions — are made public in the coming weeks.

More variant news

-

Breakthrough case reporting: Once again, outside researchers do the CDC’s job

In May, the CDC switched from tracking and reporting all cases that occur in vaccinated Americans to reporting only those that cause hospitalizations or deaths. At the time, I criticized this move as a lazy choice that left the U.S. without critical information as Delta and other variants spread through the country.

Now, Delta is causing the vast majority of cases—and the CDC still isn’t reporting on non-severe breakthroughs. As a result, entities outside the federal government are once again compiling data from states in order to fill in gaps left by the national public health agency.

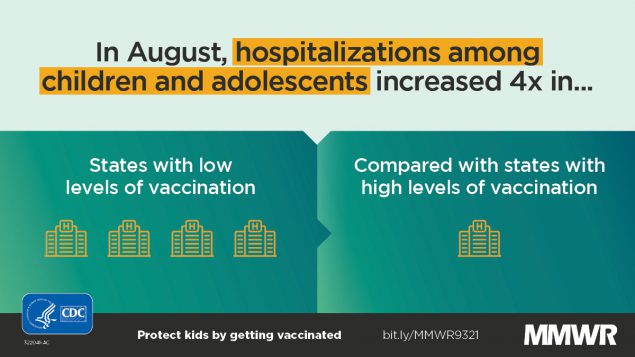

On Friday, both Bloomberg and NBC published breakthrough case analyses. Bloomberg reported 112,000 total breakthrough cases from 35 states, as of the end of July. This is a tiny fraction of the vaccinated population—over 164 million Americans—but it is far higher than the national breakthrough case number reported by the CDC in May, pre-reporting switch.

Bloomberg’s report includes plenty of expert critiques of the CDC’s May decision, suggesting that the lack of data led to many local public health officials flying blind as Delta spread.

With better understanding of how delta spreads, different public health measures or warnings could have been put in place for vaccinated people, said Rachael Piltch-Loeb, a Harvard Chan School of Public Health researcher on public health emergency responses.

According to NBC, America’s breakthrough case total is even higher: at least 125,000 cases from 38 states. Nine states, including Pennsylvania and Missouri, failed to provide NBC with any breakthrough case information, while 11 did not provide death and hospitalization numbers. Still, these cases have clearly increased substantially in the past two months, NBC reports:

In Utah on June 2, 2021, just 27 or 8 percent of the 312 new cases in the state were breakthrough cases. As of July 26 there were 519 new cases and almost 20 percent or 94 were breakthroughs, according to state data.

Now, it’s important to emphasize that breakthrough cases are still very rare and very mild, compared with non-breakthrough COVID-19. The 125,000 cases reported by NBC comprise less than 0.08% of the 164 million Americans who’ve been fully vaccinated. And the CDC reports just 6,600 severe breakthrough cases (leading to hospitalization and/or death) as of July 26.

Any news article, headline, or tweet about breakthroughs should make that denominator explicitly clear—something that one NBC reporter failed to do when sharing his outlet’s story on Friday.

Also on Friday, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) published detailed annotations on state breakthrough case reporting. 24 states and D.C. have provided public data on this topic, according to KFF; some are reporting data regularly, while others have included the information in limited press releases and other reports.

If your state is one of the 26 states not providing any public breakthrough case data at all, I’d recommend reaching out to the state public health agency and asking why not. Yes, it’s challenging to identify these cases when vaccinated people tend to have mild symptoms and might not think to get a test. And yes, the vast majority of people who have a breakthrough case will likely be fine in a couple of weeks. But the information is vital as Delta continues to wreak havoc across the country.

More vaccine reporting

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.

- Sources and updates, November 12

-

Unpacking Delta numbers from this week’s headlines

It should be no surprise, at this point in the summer, that Delta (B.1.617.2) is bad news. From the moment it was identified in India, this variant has been linked to rapid transmission and rapid case increases, even in areas where the vaccination rates are high.

This week, however, the CDC’s changed mask guidance—combined with new reports on breakthrough cases associated with Delta—has triggered widespread conversation about precisely how much damage this variant can do. “I’ve not seen this level of anxiety from everyone since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Katelyn Jetelina wrote in her newsletter Friday.

In the CDD today, I’m unpacking six key statements that you’ve likely seen in recent headlines, including where the statistics came from and what they mean for you.

1. Delta causes a viral load 1,000 times higher than the original coronavirus strain.

This number comes from a recent study in Guangzhou, China that was published as a preprint earlier in July. The researchers looked at viral load, a measurement of how much virus DNA is present in patients’ test samples; a higher viral load generally means the patient can infect more people, though it’s not a one-to-one relationship (more on that below).

Based on measurements from 62 people infected with Delta, the researchers concluded that Delta patients have about 1,000 times more virus in their bodies compared to patients infected with the original coronavirus strain in early 2020. This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed, but outside experts have cited it as evidence behind Delta’s super-spreading ability.

For more explanation on how Delta differs from past coronavirus strains, check out this KHN story by Liz Szabo.

2. Delta causes similar viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people who get infected.

This finding comes from a highly anticipated CDC report published Friday in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). CDC researchers measured viral loads—remember, a reflection of how much virus DNA is in a patient’s body—in vaccinated and unvaccinated people who got infected during an outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts. They found that the two groups had similar measurements, on average. Test samples in this outbreak were also sequenced; 90% of cases in the outbreak were definitively caused by Delta.

It’s important to be precise when we talk about this CDC report, because viral load is just one specific measurement. While the viral load can reflect how capable someone is of transmitting the coronavirus, the CDC’s data do not definitively tell us that vaccinated and unvaccinated people are equally capable of transmitting Delta.

Experts commenting on the CDC’s findings have said that other factors, such as length of infection and virus presence in a patient’s nose and mouth, also play into coronavirus transmission.For example, here’s a quote from a Science News story discussing the CDC’s findings:

The result “just gives you an indication of how much viral RNA is in the sample, it tells you nothing about infectiousness,” says Susan Butler-Wu, a clinical microbiologist at the University of Southern California. These data “are a cause for concern, but this is not a definitive answer on transmissibility” from vaccinated people, she says.

And here’s a Twitter thread from a vaccine scientist discussing how the CDC has conflated viral load measurements with actual transmission:

In other words: vaccinated people are not capable of spreading Delta to the same degree as the unvaccinated. The infection and transmission risks for vaccinated people are still much lower. Here’s one reason why…

3. A breakthrough infection will be over faster than a non-breakthrough infection.

This finding comes from a study out of Singapore, published yesterday as a preprint. Researchers looked at viral loads over time for patients infected with Delta, comparing numbers for those patients who had and had not been vaccinated. They found that the viral load decreased more quickly in those vaccinated patients who had a breakthrough case, signifying that vaccinated patients both recover more quickly and lose their ability to get someone else infected more quickly.

In other words, when a vaccinated person has a breakthrough case, their immune system is more prepared to face the coronavirus. That prepped immune system will help the person avoid severe disease, while also getting the virus out of the body more quickly than the immune system would be able to without a vaccine’s help.

This study is not yet peer-reviewed, but it aligns with other research showing that vaccinated people with breakthrough cases tend to have mild symptoms and spend less time being contagious.

4. An interaction of one second is enough time for Delta to spread from one person to another.

In spring 2020, public health leaders agreed on a rule of thumb for COVID-19 risk: if you were indoors with someone, unmasked, for at least 15 minutes, that person qualified as a “close contact” who could give you the coronavirus, or vice versa. Now, with Delta, the equivalent of that 15-minute close contact is one second. I first saw this statistic in a STAT News interview with epidemiologist Dr. Céline Gounder, but it’s been reported in other publications as well.

Let me emphasize here, though, that this one-second rule applies to indoor transmission. We don’t yet know how much Delta increases the risk of outdoor transmission, which was almost entirely negligible for past variants.

5. The average person with Delta infects at least twice as many others as the average person with the original coronavirus strain.

In spring 2020, the average person who got sick with COVID-19 would infect a couple of others, while a select few would cause superspreading events. Now, we’re learning that the average person who gets Delta can infect more. An internal CDC report leaked by the Washington Post says that Delta may infect eight or nine people on average and spreads “as easily as chickenpox.”

While this comparison is obviously pretty concerning, outside experts have been skeptical of the CDC’s generalization of data from that one Massachusetts outbreak. Plus, the CDC’s estimate of Delta’s capacity for infection is higher than estimates we’ve seen from other sources. Studies out of England suggest that the variant infects five to seven people on average—still high, but not quite chickenpox levels.

6. Hospitalizations are rising in undervaccinated areas, while well-vaccinated areas are on the alert.

Florida has been setting COVID-19 records recently. The state now has more people in the hospital with COVID-19 than at any other time during the pandemic, including the winter surge.

Meanwhile, hospitalizations in Texas are up more than 300% from lows in late June. Austin is running out of ICU beds. Louisiana, Arkansas, and Nevada have all seen more than 10 new COVID-19 patients for every 100,000 residents in the past week. And the healthcare workers treating these patients are burnt out from over a year of pandemic work.

In well-vaccinated areas, hospitalizations are low for now; even with Delta, the vaccines do a great job of protecting people against severe disease and death. But hospitals in these cities are still on high alert, ready to treat unvaccinated patients and those seniors, immunocompromised patients, and others for whom the vaccines may not be as effective.

For example, see this thread from University of California San Francisco medical professor Bob Wachter. (San Francisco has the highest vaccination rate of any city in America.)

TL;DR

The TL;DR here is: Delta is way more contagious than any variant we’ve seen before. For unvaccinated people, any indoor, unmasked interaction with someone who has Delta—even a very short interaction—is enough for you to get infected. For vaccinated people, the risk of getting and spreading Delta is elevated compared to past coronavirus strains, but it is still far lower than the risk for unvaccinated people.

So, when the CDC suggests that vaccinated people go back to mask-wearing (if you ever stopped), the agency is saying, wear a mask on behalf of the unvaccinated people around you. Those who are vaccinated are at more risk now than they were in May or June, but vaccination is still the best protection we have against infection, transmission, and—most importantly—severe COVID-19 disease.

Or, to quote WNYC health and science editor Nsikan Akpan: “The vaccines will keep you from dying. Masks will keep away infections. Otherwise, the COVID odds are against you.”

More variant reporting

-

The Delta variant is taking over the world

The Delta variant is now dominant in the U.S., but our high vaccination rates still put us in a much better position than the rest of the world—which is facing the super-contagious variant largely unprotected.

Let’s look at how the U.S.’s situation compares:

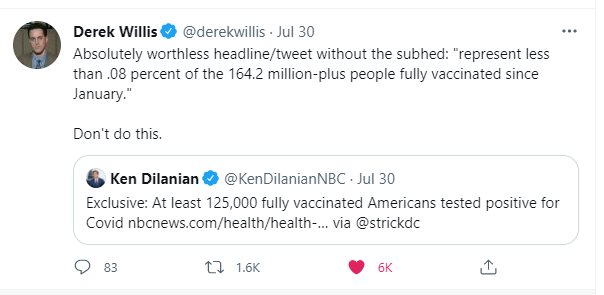

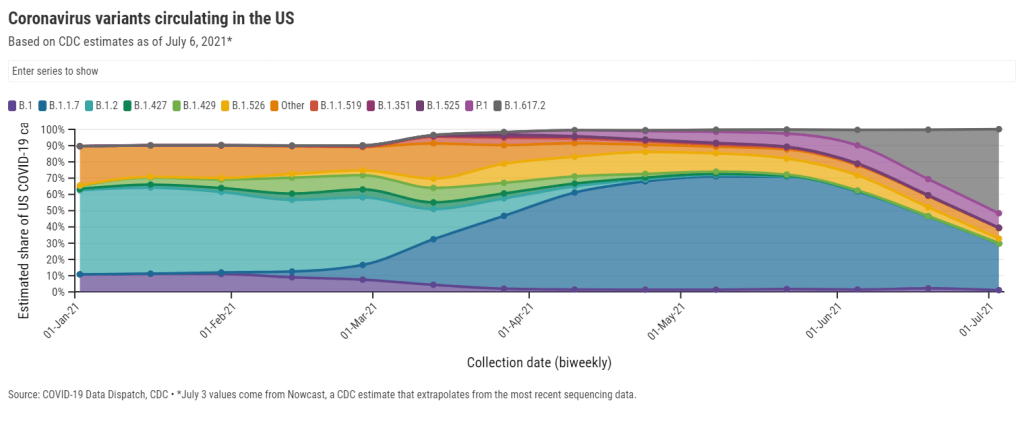

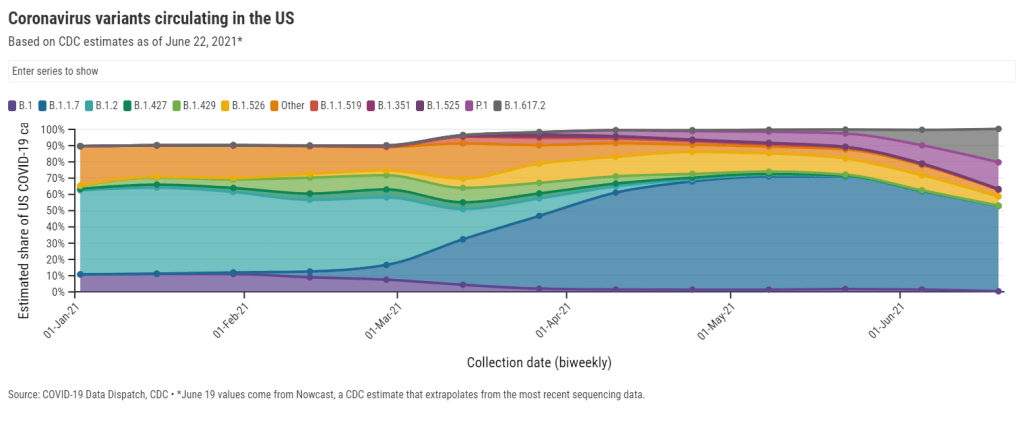

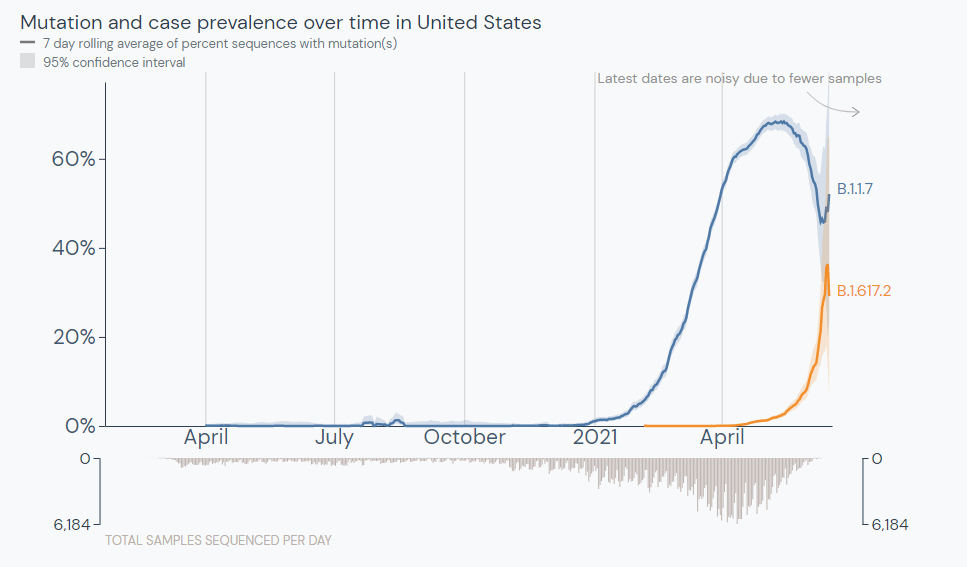

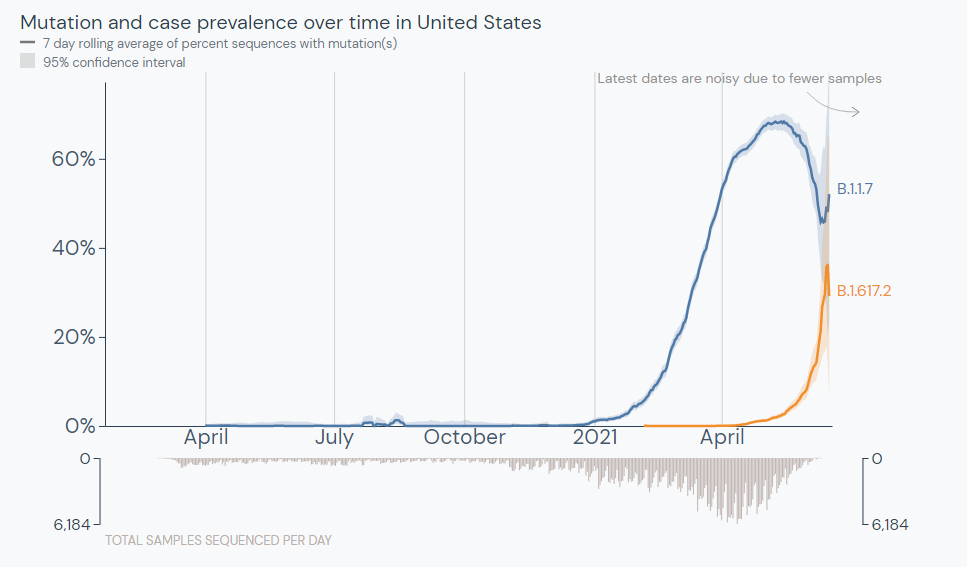

U.S.: Delta now causes 52% of new cases, according to the latest Nowcast estimate from the CDC. (This estimate is pegged to July 3, so we can assume the true number is higher now.) It has outcompeted other concerning variants here, including Alpha/B.1.1.7 (now at 29%), Gamma/P.1 (now at 9%), and the New York City and California variants (all well under 5%). And Delta has taken hold in unvaccinated parts of the country, especially the Midwest and Mountain West.

Israel and the U.K.: Both of these countries—lauded for their successful vaccination campaigns—are seeing Delta spikes. Research from Israel has shown that, while the mRNA vaccines are still very good at protecting against Delta-caused severe COVID-19, these vaccines are not as effective against Delta-caused infection. As a result, public health experts who previously said that 70% vaccination could confer herd immunity are now calling for higher goals.

Japan: The Tokyo Olympics will no longer allow spectators after Japan declared a state of emergency. The country is seeing another spike in infections connected to the Delta variant, and just over a quarter of the population has received a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. I argued in a recent CDD issue that, if spectators are allowed, the Olympics could turn into a superspreading event.

Australia: Several major cities are on lockdown in the face of a new, Delta-caused surge following a party where every single unvaccinated attendee was infected. Unlike other large countries that faced significant outbreaks, Australia has successfully used lockdowns to keep COVID-19 out: the country has under 1,000 deaths total. But the lockdown strategy has diminished incentives for Australians to get vaccinated; under 5% of the population has received a shot. Will lockdowns work against Delta, or does Australia need more shots now?

India: Delta was first identified in India, tied to a massive surge in the country earlier this spring. Now, India has also become the site of a Delta mutation, unofficially called “Delta Plus.” This new variant has an extra spike protein mutation; it may be even more transmissible and even better at invading people’s immune systems than the original Delta, though scientists are still investigating. India continues to see tens of thousands of new cases every day.

Africa: Across this continent, countries are seeing their highest case numbers yet; more than 20 countries are experiencing third waves. Most African countries have fewer genetic sequencing resources than the U.S. and other wealthier nations, but the data we do have are shocking: former CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden reported that, in Uganda, Delta was detected in 97% of case samples. Meanwhile, vaccine delivery to these countries is behind schedule—Nature reports that many people in African countries and other low-income nations will not get their shots until 2023.

South America: This continent is also under-vaccinated, and is facing threats from Delta as well as Lambda, a variant detected in Peru last year. While Lambda is not as fast-spreading as other variants, it has become the dominant variant in Peru and has been identified in at least 29 other countries. Peru has the highest COVID-19 death rate in the world, and scientists are concerned that Lambda may be more fatal than other variants. Studies on this variant are currently underway.

In short: basically every region of the world right now is seeing COVID-19 spikes caused by Delta. More than 20 countries are experiencing exponential case growth, according to the WHO:

We’ve already seen more COVID-19 deaths worldwide so far in 2021 than in the entirety of 2020. Without more widespread vaccination, treatments, and testing, the numbers will only get worse.

More international reporting

-

Breakthrough cases: What we know right now

Washington is one of the states reporting high levels of detail about breakthrough cases. Screenshot via June 23 report. For the past few months, we’ve been watching the vaccines and variants race in real time. With every new case, the coronavirus has the opportunity to mutate—and many scientists agree that it will inevitably mutate into a viral variant capable of outsmarting our current vaccines.

How will we know when that happens? Through genomic surveillance, examining the structure of coronavirus lineages that arise in the U.S. and globally. While epidemiologists may consider any new outbreak a possible source of new variants, one key way to monitor the virus/variant race is by analyzing breakthrough cases—those infections that occur after someone has been fully vaccinated.

In May, the CDC changed how it tracks breakthrough cases: the agency now only investigates and reports those breakthrough cases that result in hospitalizations or deaths. I wrote about this in May, but a new analysis from COVID Tracking Project alums and the Rockefeller Foundation provides more detail on the situation.

A couple of highlights from this new analysis:

- 15 states regularly report some degree of information about vaccine breakthroughs, some including hospitalizations and deaths.

- Six states report sequencing results identifying viral lineages of their breakthrough cases: Nebraska, Arkansas, Alaska, Montana, Oregon, and Washington.

- Washington and Oregon are unique in providing limited demographic data about their breakthrough cases.

- Several more states have reported breakthrough cases in isolated press briefings or media reports, rather than including this vital information in regular reports or on dashboards.

- When the CDC stopped reporting breakthrough infections that did not result in severe disease, the number of breakthrough cases reported dropped dramatically.

- We need more data collection and reporting about these cases, on both state and federal levels. Better coordination between healthcare facilities, laboratories, and public health agencies would help.

Vaccine breakthrough cases are kind-of a data black box right now. We don’t know exactly how many are happening, where they are, or—most importantly—which variants they’re tied to. The Rockefeller Foundation is working to increase global collaboration for genomic sequencing and data sharing via a new Pandemic Prevention Institute.

Luckily, there is a lot we do know from another side of the vaccine/variant race: vaccine studies have consistently brought good news about how well our current vaccines work against variants. The mRNA vaccines in particular are highly effective, especially after one has completed a two-dose regimen. If you’d like more details, watch Dr. Anthony Fauci in Thursday’s White House COVID-19 briefing, starting about 14 minutes in.

New research, out this week, confirmed that even the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine works well against the Delta variant. The company reported that, after a patient receives this vaccine, blood antibody levels are high enough to beat off an infection from Delta. In other words, people who got the J&J shot do not need to rush to get a booster shot from an mRNA vaccine (a recent debate topic among some experts).

Again, we’ll need more genomic surveillance to carefully watch for the variant that inevitably does beat our vaccines. But for now, the vaccinated are safe from variants—and getting vaccinated remains the top protection for those who aren’t yet.

More variant reporting

-

Delta and Gamma are starting to dominate

This week, the CDC titled its weekly COVID-19 data report, “Keep Variants at Bay. Get Vaccinated Today.” I love a good rhyme, but the report also makes a valuable point: vaccinations not only protect individuals from coronavirus variants, they also reduce community transmission—slowing down future viral mutation.

Delta, or B.1.617.2, is particularly dangerous. As I’ve written before, this variant spreads much more quickly than other strains of the coronavirus and may cause more severe illness, though scientists are still investigating that second point. Thanks to this variant, it’s now much more dangerous to be unvaccinated than it was a year ago.

The Delta variant was first linked to a surge in India, but it’s now become dominant in the U.K., Russia, Indonesia, and other countries. As Eric Topol recently pointed out on Twitter, the variant’s dominance has led to sharp rises in cases—and in deaths—for these nations.

The U.S. is somewhat distinct from the U.K., though, because we had a more diverse group of variants circulating here before Delta hit. In the U.K., Delta arrived in a coronavirus pool that was 90% Alpha (B.1.1.7); here, the Alpha variant peaked at about 70%, with several other variants of concern also circulating.

In other words: we can’t forget about Gamma. Gamma, or P.1, was first identified in Brazil late in 2020. While it’s not quite as fast-spreading as Delta, it’s also highly transmissible and may be able to more easily re-infect those who have already recovered from a past coronavirus infection.

The Gamma variant now causes an estimated 16% of cases in the U.S. while the Delta variant causes 21%, per the CDC’s most recent data (as of June 19). Both are rapidly increasing as the Alpha variant declines, now causing an estimated 53% of cases.

A recent preprint from Helix researchers suggests an even starker change in the U.S.’s variant makeup. Helix’s analysis shows that Alpha dropped from 70% of cases in April 2020 to 42% of cases, within about six weeks.

Delta will certainly dominate the U.S. in a few weeks, but Gamma will likely be a top case-causer as well. Other variants that once worried me—like those that originated in New York and California—are getting solidly outcompeted.

The TL;DR here is, get vaccinated. Don’t wait. Tell everyone you know.

More variant reporting

-

Featured sources, June 20

- CDC adds more data on Delta: The CDC formally classified the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) as a Variant of Concern this week, and updated its Variant Proportions tracker page accordingly. This means data are now available on the variant’s state-by-state and regional prevalence—though the state-by-state figures are as of May 22 due to data lag.

- AMA survey on doctor vaccinations: The American Medical Association (AMA) recently released survey data showing that 96% of U.S. physicians have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, as of June 8. The 14-page report includes demographic data and other details.

- Rural hospital closures: The North Carolina Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina tracks hospitals in rural areas that close or otherwise stop providing in-patient care. The database includes 181 hospitals that have closed between 2005 and 2021, available in both an interactive map and a downloadable Excel file.

- Health Security Net: This is a public repository including over 1,200 pandemic-related documents—research, hearings, government papers, and more—from the decades leading up to 2020, compiled by Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Science and Security. It’s built for scholars, journalists, and other researchers to analyze past and present responses to public health crises.

-

National numbers, June 20

The Delta variant is outcompeting the Alpha variant in the U.S. Source: outbreak.info In the past week (June 11 through 17), the U.S. reported about 80,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 11,000 new cases each day

- 24 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 19% fewer new cases than last week (June 5-11)

Last week, America also saw:

- 13,800 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (4.2 for every 100,000 people)

- 2,000 new COVID-19 deaths (0.6 for every 100,000 people)

- 66% of new cases in the country now Alpha-caused (as of June 5)

- 10% of new cases now Delta-caused (as of June 5)

- An average of 1.3 million vaccinations per day (per Bloomberg)

Data note: The CDC skipped an update on Friday in honor of Juneteenth, so this update is a day off from our usual schedule (reflecting a Friday-Thursday week instead of a Saturday-Friday week).

Last week, I wrote that I’m getting very worried about the Delta variant (or B.1.617.2, the variant first identified in India). Now, I’m even more worried.

The CDC updated its variant prevalence estimates this week, reporting that the variant makes up 10% of U.S. cases as of June 5. This aligns with other estimates I cited last week, and suggests that the variant is spreading here at a truly rapid pace—its prevalence multiplied by four times in two weeks, according to CDC data.

That means Delta could be the dominant variant in the U.S. within a month, if not sooner. Vaccinated Americans are well-protected against this variant, but those who are unvaccinated need to get their shots—and soon.

Vaccinations have picked up a bit this week, per Bloomberg. In the past week, we’ve seen 1.3 million shots administered a day. Still, researchers have estimated that the U.S. is likely to fall short of Biden’s 70%-by-July-4 goal. Disparities persist in the rollout as well.

Meanwhile, national case numbers continue to drop (though not as dramatically as the drops a few weeks ago), while hospitalization and death numbers remain low. Notably, the vast majority of COVID-19 patients currently in hospitals are unvaccinated.

When New York Governor Cuomo set off fireworks on Tuesday to celebrate the state’s full reopening, my girlfriend and I went up to our building’s roof to watch—only to be unable to see the show. We later realized that the fireworks were set off in New York Harbor, visible mostly to lower Manhattan (but not the outer boroughs, which have felt the brunt of COVID-19). It felt like an apt metaphor for the current state of the pandemic.