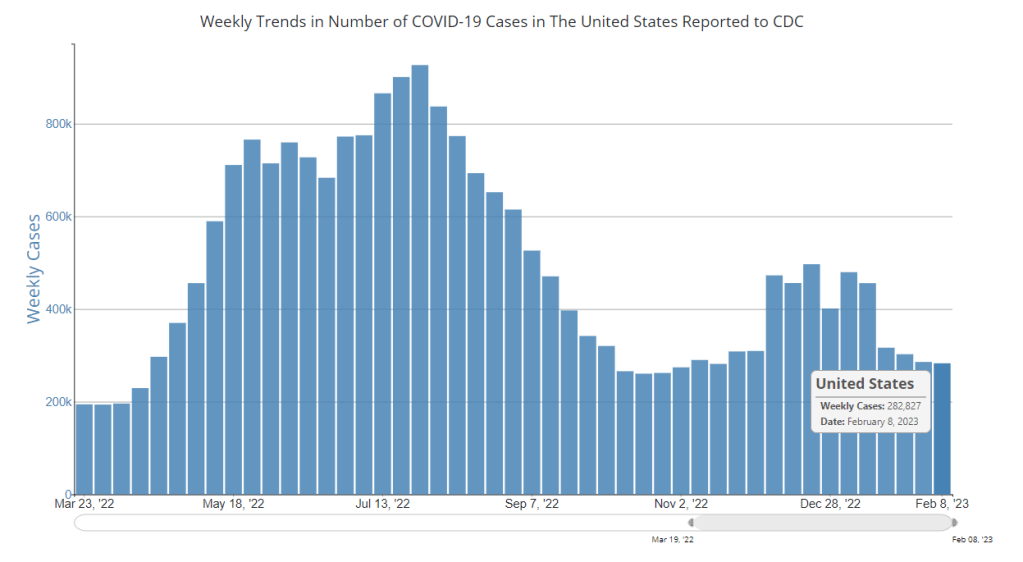

In the past week (May 14 through 20), the U.S. reported about 8,300 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,200 new admissions each day

- 2.5 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 11% fewer new admissions than last week (May 7-13)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

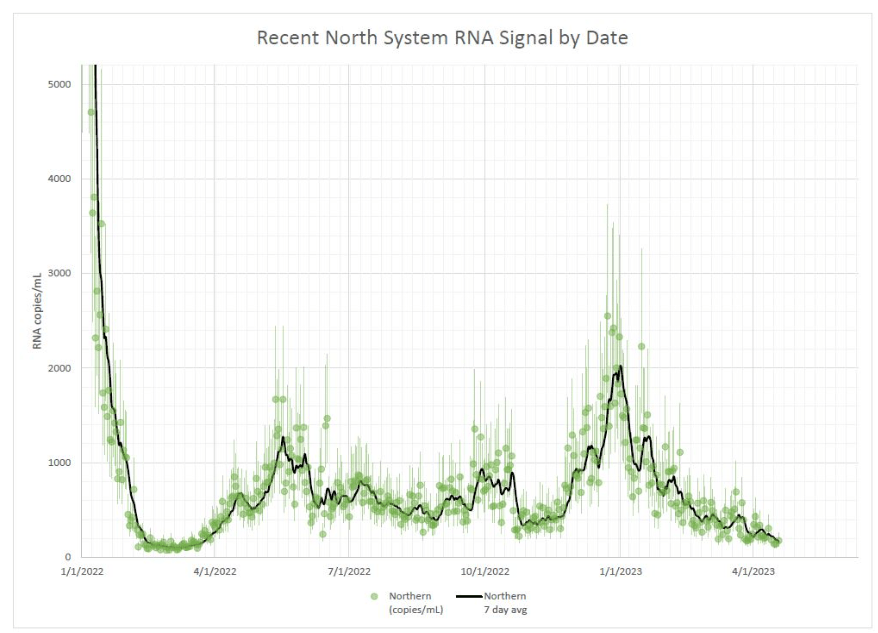

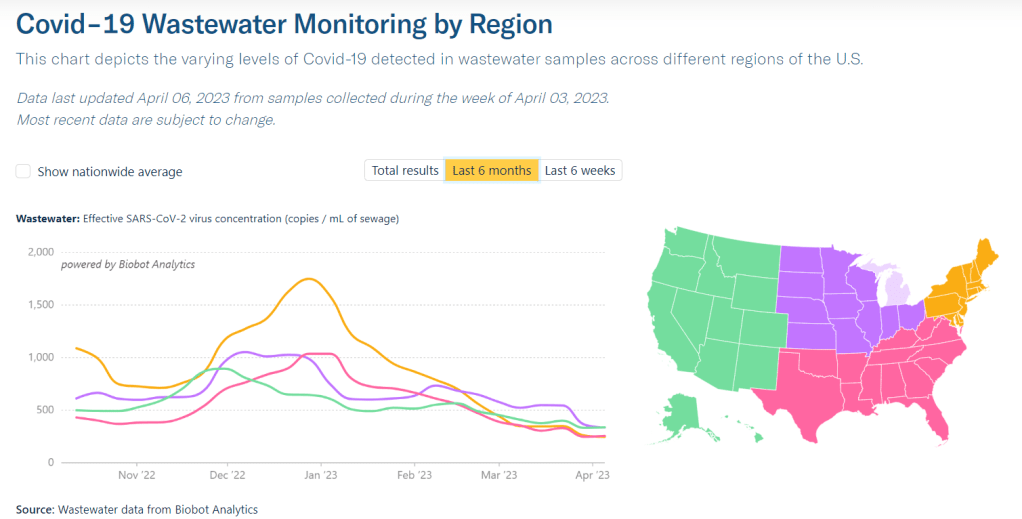

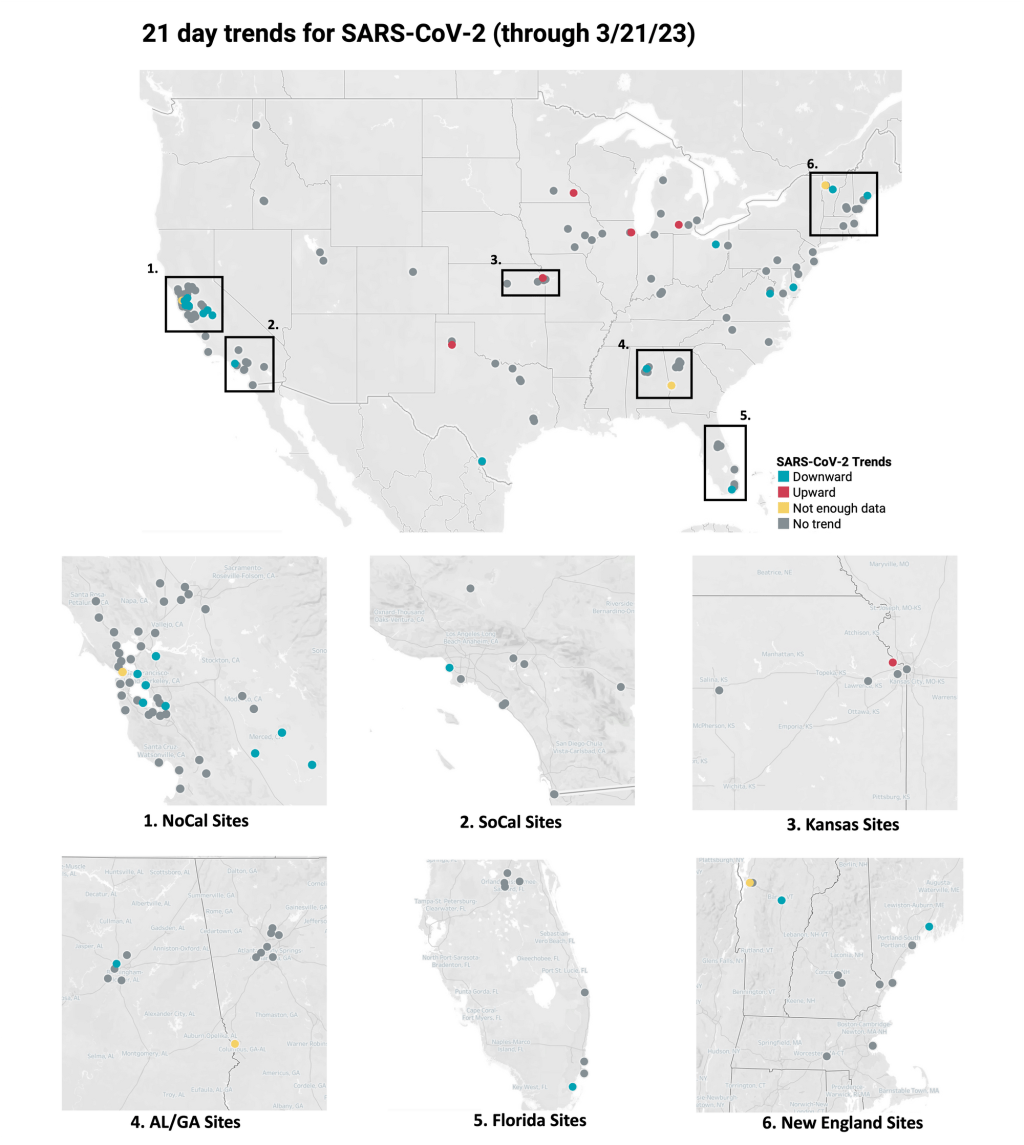

- A 16% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of May 24, per Biobot’s dashboard)

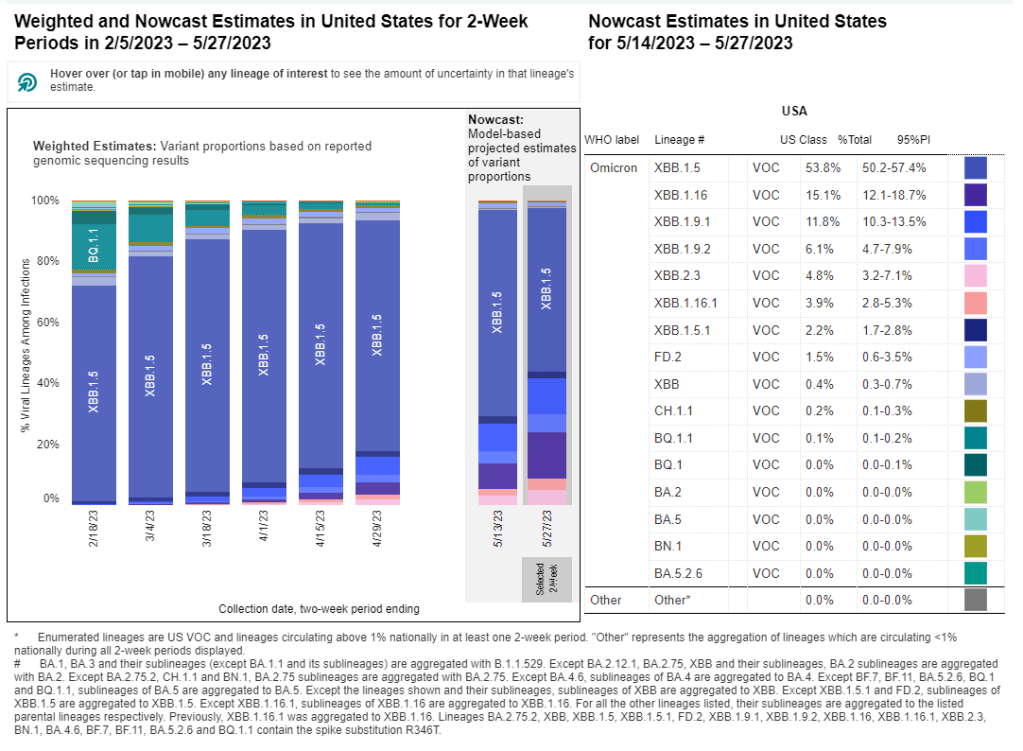

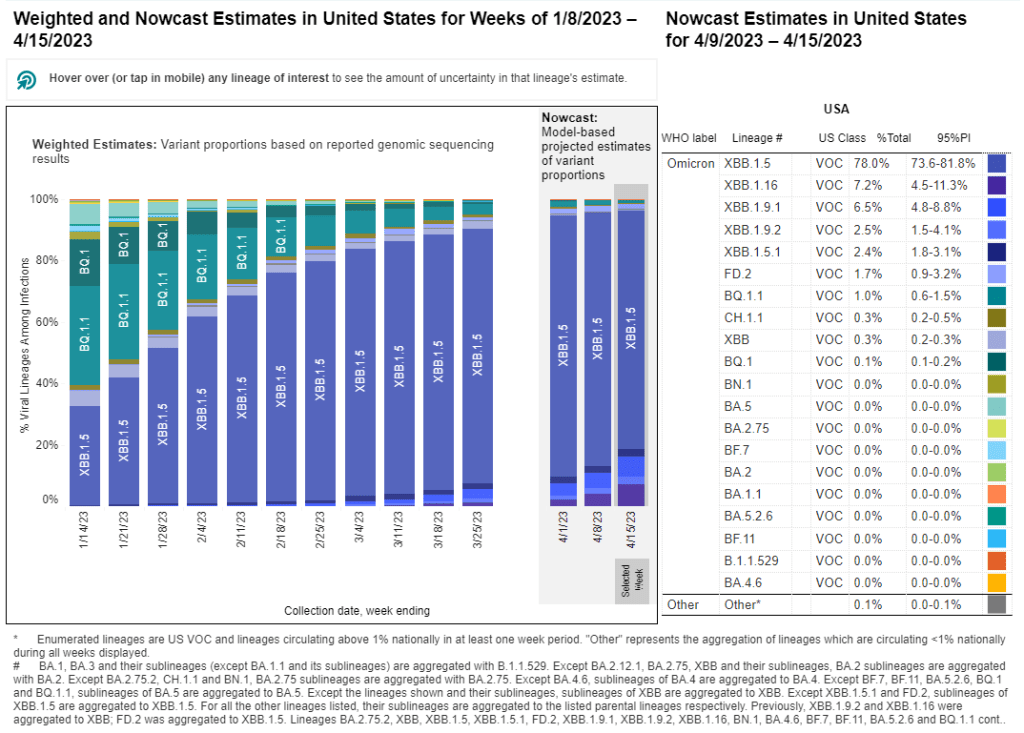

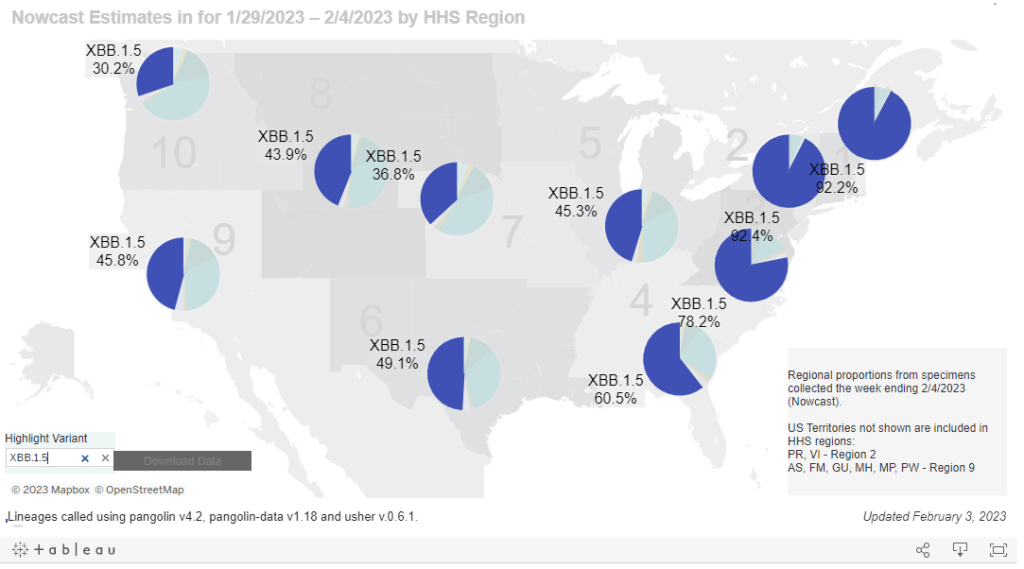

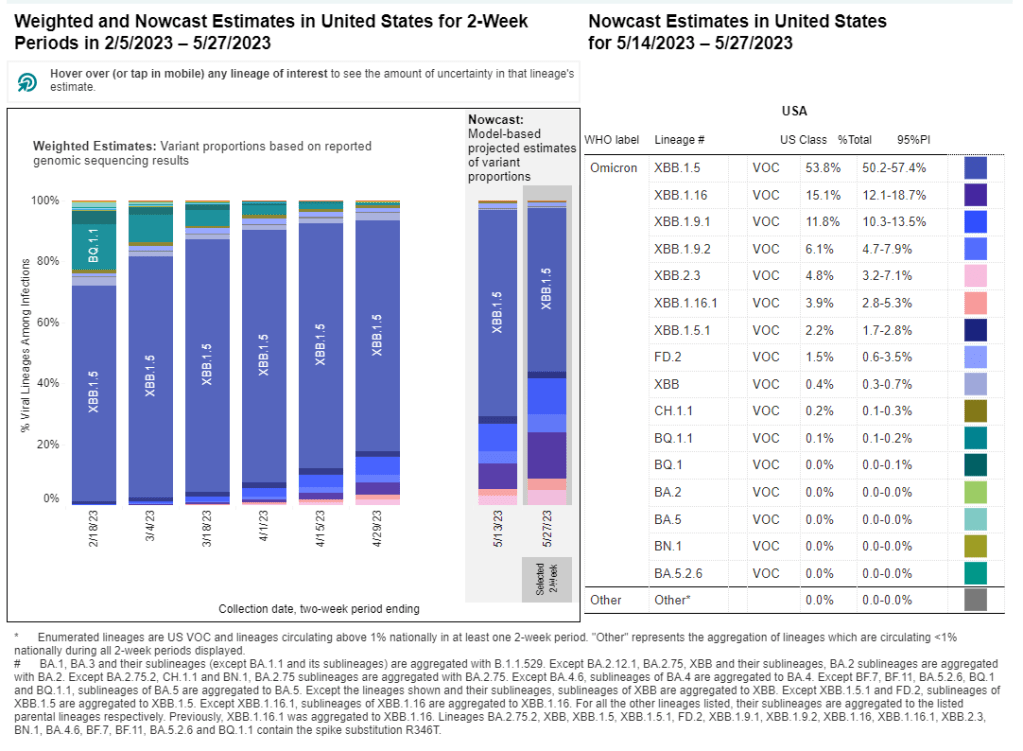

- 54% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 19% by XBB.1.16; 18% by XBB.1.9 (as of May 27)

The COVID-19 plateau continues, with hospital admissions and viral levels in wastewater (the two main metrics I’m looking at these days) both trending slightly down at the national level. Newer Omicron variants are still on the rise, but don’t seem to be impacting transmission much yet.

Hospitalizations continue to trend slightly down across the board, though hospitals are still reporting more than 1,000 new COVID-19 patients each day. The vast majority of U.S. counties have low hospitalization levels, according to the CDC, with just 14 counties in the medium or high categories.

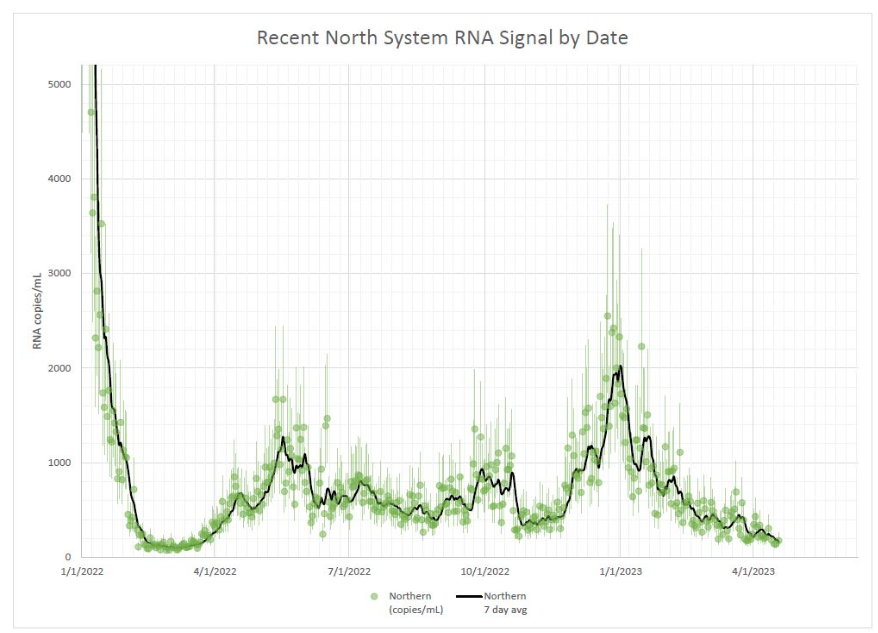

Coronavirus levels in wastewater are following a similar pattern: trending down very slightly, continuing the middling plateau of the last couple of months. All four major regions are still in this holding pattern, according to Biobot’s data.

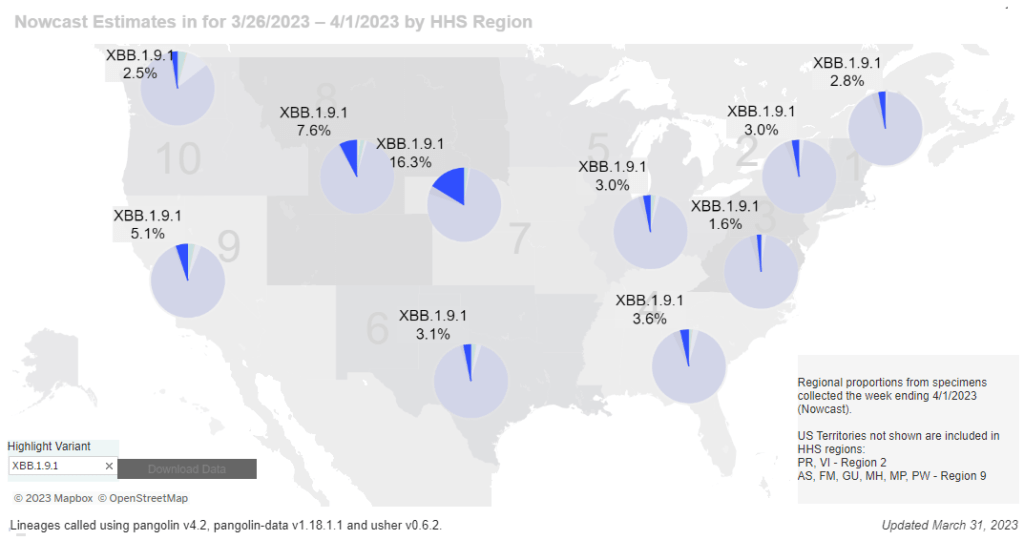

We have new variant data this week, as the CDC is now on a biweekly schedule for updates. XBB.1.5 caused just over half of new cases in the U.S. in the two weeks ending May 27, as it slowly gets outcompeted by newer versions of Omicron. XBB.1.16 and XBB.1.9 continue to rise, causing 19% and 18% of hew cases respectively.

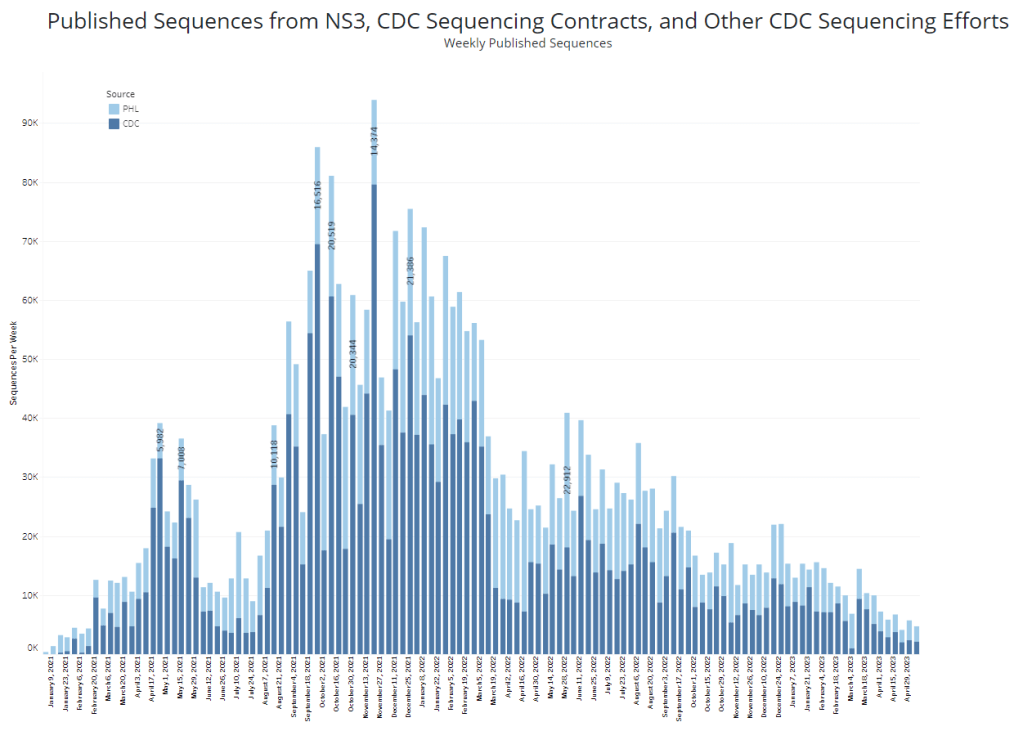

XBB.1.16 is most prevalent on the West Coast, the Northeast, and the Gulf Coast states, while XBB.1.9 is most prevalent in the Midwest, according to the CDC—though these estimates are becoming less reliable over time, since so few COVID-19 samples are sequenced.

The CDC has also recently added national and regional COVID-19 test positivity data back to its dashboard, representing tests conducted by labs in the CDC’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System.

Nationally, test positivity is trending down, at just under 5% of COVID-19 tests (in this lab network) returning positive results in the most recent week of data. Test positivity is trending up slightly in the Northeast and New York/New Jersey regions; I’ll be following to see if this continues in the coming weeks.

Finally, a bit of good news: excess deaths in the U.S. have returned to baseline in the last couple of months. While hundreds are still dying from COVID-19 every day, the excess death trend suggests that the disease is currently not causing a significant ripple effect on overall mortality the way that it did in earlier stages of the pandemic. (Of course, this could change with a new surge.)