Since last fall, I’ve been fascinated by exposure notification apps. These phone applications use Bluetooth to track people’s close contacts and inform them when a contact has tested positive for COVID-19. As I wrote back in October, though, data on the apps are few and far between, leaving me with a lot of questions about how many people actually have these apps on their phones—and how well they’re working at preventing COVID-19 spread.

This week, I put those questions to Jenny Wanger, co-founder of the TCN Coalition and Director of Programs at the Linux Foundation of Public Health. TCN stands for Temporary Contact Numbers, a privacy-first contact tracing protocol developed by an international group of developers and public health experts. As a product manager, Wanger was instrumental in initial collaboration between developers in the U.S. and Europe, and now helps more U.S. states and countries bring exposure notification apps to their populations.

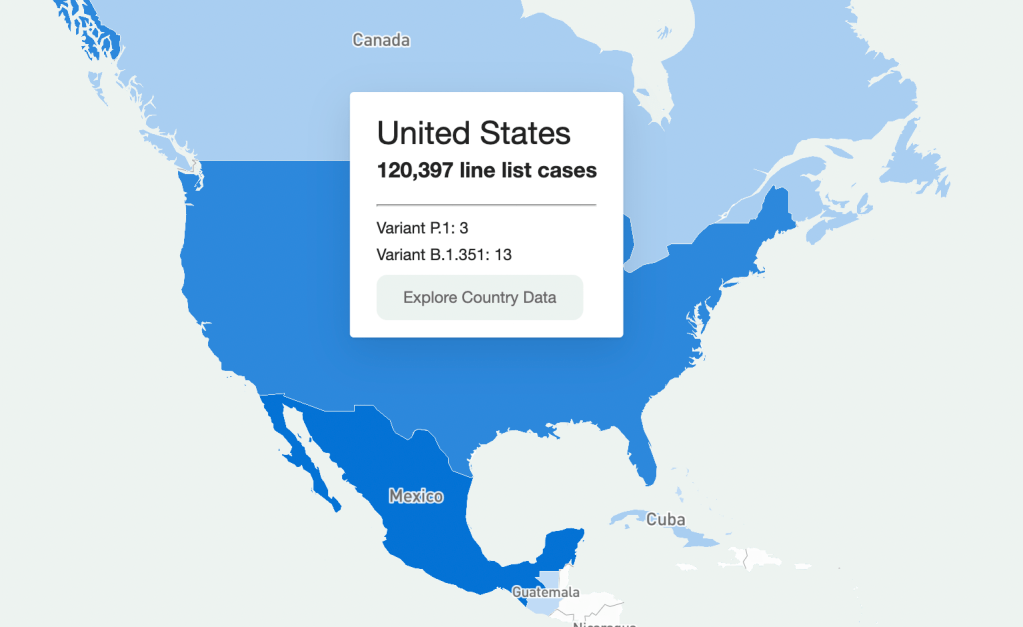

Wanger originally joined the team as what she thought would be a two-week break between her pandemic-driven layoff and a search for new jobs. Now, as the TCN Coalition approaches its one-year anniversary, exposure notification apps are live on 150 million phones worldwide. While data are still scarce for the U.S., research from other countries has shown how effective these apps may be in stopping transmission.

My conversation with Wanger ranged from the privacy-first design of these apps, to how some countries encouraged their use, to how this project has differed from other apps she’s worked on.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: To start off, could you give me some background on how you got involved with the TCN colatition and what led you to this role you’re in now?

Jenny Wanger: My previous company did a very large round of layoffs with the beginning of the pandemic because the economics changed quite dramatically, and I was caught in that crossfire. And a couple of days later, a friend reached out and asked whether I was available to help—he was like, “I need a product manager for this thing, we’re trying to launch these apps for the pandemic. It should be, like, two weeks, and then you can go back to whatever.” So I signed up for that. I thought, sure, I’m not gonna be getting a job in the next two weeks.

A lot of what we were trying to do, the person who brought me on, was to convince people to use the same system and be interoperable with each other, to have more collaboration across projects. As opposed to all of these different apps being built, none of which would be able to work with each other. We found that there was somebody doing the same thing over on the European side, which was Andreas [Gebhard].

We scheduled a meeting with all of the people we were trying to convince to do something interoperable and all of their people, and out of that meeting came the TCN Coalition. Andreas suggested the name TCN Coalition pretty much on a whim, which we’ve learned, never try to name a project in a meeting with other people there, because it will haunt you for a long time.

That’s what we ended up with… TCN Coalition was formed, and we started trying to get everybody to build an interoperable standard and protocol and share that kind-of thing together. It was probably a week or two later that Apple and Google announced that they were going to be having APIs available to use. We weren’t totally sure what to do with that, so we kept moving forward, waiting for more information from them, and then also coaching everybody, like let’s make this interoperable with Apple and Google, that fixes a lot of problems that we weren’t able to fix otherwise.

We kept growing, we started building out some relationships with public health authorities. And meanwhile, somebody started poking around in our area from the Linux Foundation… Eventually, it became clear that we were not gonna be able to grow to the degree that we wanted without a business model, and Linux Foundation brought that piece of the puzzle. So we merged our community to seed the Linux Foundation Public Health, and Linux Foundation Public Health brought in a business model and some funding that allowed us to keep doing the work that we were doing. We were also getting to the point where a bunch of our volunteers were saying that they needed to go back to having jobs… There was a lot of early momentum, and that slowed down over time, understandably.

So yeah, that’s how TCN ended up merging in with LFPH. That man who was poking around TCN way back at the beginning was a guy—his name is Dan Kohn, he unfortunately passed away from cancer at the beginning of November. With that, I ended up taking on more of a leadership role in LFPH than I’d anticipated. We eventually got a new executive director at this point, and I’ve been part of the leadership team throughout. That’s sort-of the high level story.

BL: Thank you. So, how did your background—you do product management stuff, right, how did that lead into connecting coders and running this coalition?

JW: As a product manager, I’ve always been focused on how to get something built that actually meets the needs of a certain population, and is actually useful. There’s two sides to that. One is the project management side, of like, okay, we need to get this done.

But much more relevant has been, on the product side, we need to make sure that we’re building things that—there are so many different players in the space, with an exposure notification app or now as we’re looking at vaccine credentials. You’ve got the public health authority, who is trying to achieve public health goals. You’ve got the end user, who actually is going to have this product running on their phone. You have Apple and Google, or anybody else who is controlling the app stores, that have their own needs. You’ve got the companies that are actually building these tools out, building out these products who are trying to hit their own goals. It’s a lot of different players, and I think where my background as a product manager has really helped has been, I’ve got frameworks and tools of how to balance all these different needs, figure out how to move things forward and get people working together, get them on the same page, to actually have something go to market that does what we think it’s supposed to do.

BL: Right. To talk about the product itself now, can you explain how an exposure notification app works? Like, how would you explain it to someone who’s not very tech savvy.

JW: The way I explain exposure notification is essentially that your phone uses Bluetooth to detect whether other phones are nearby. They do this by broadcasting random numbers, and the other phones listen for these random numbers and write them down in a database.

That’s really all that’s happening—your phone shouts out random numbers, they’re random so that they don’t track you in any way, shape, or form, they’re privacy-preserving. You’ve got that cryptographic security to it. The other phones write down the numbers, and they can’t even tell, when they get two numbers, whether they’re from the same phone or different phones. They just know, okay, if I received a number, if I wrote it down, that means I was close enough to that phone in order to be at a distance, being at risk of COVID exposure.

Then, let’s say one of those phones that you were near, the owner of that phone tests positive. They report to a central database, “Hey, I tested positive.” When this happens, all of the random numbers that that phone was broadcasting get uploaded to a central server. And what all the other phones do is, they take a look at the list on the central server of positive numbers, and they compare it to the list that’s local on their phone. If there’s a match, they look to see, like, “How long was I in the vicinity of this phone? Was it for two minutes, five minutes, 30 minutes?”

If it goes over the threshold of being near somebody who tested positive for enough time that you’re considered a close contact, then you get a notification on your phone saying, “Hey, you were exposed to COVID-19, please follow these next steps.”

The nice thing about this system is, it’s totally privacy-preserving, there’s pretty much no way for anybody to look at these random numbers and tell who’s tested positive or who hasn’t. They can’t tell who anybody else has been by. So it’s a really privacy-first system.

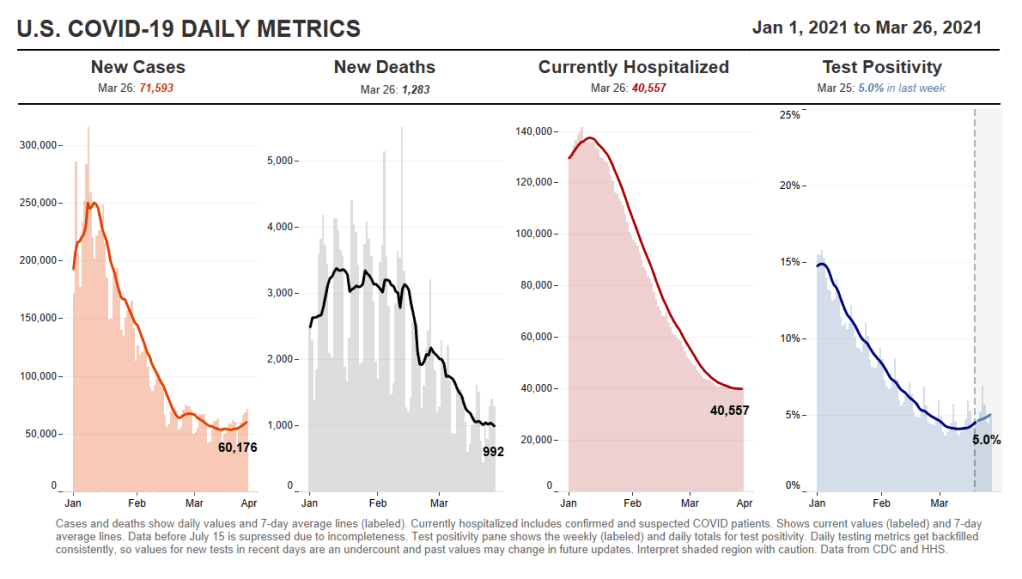

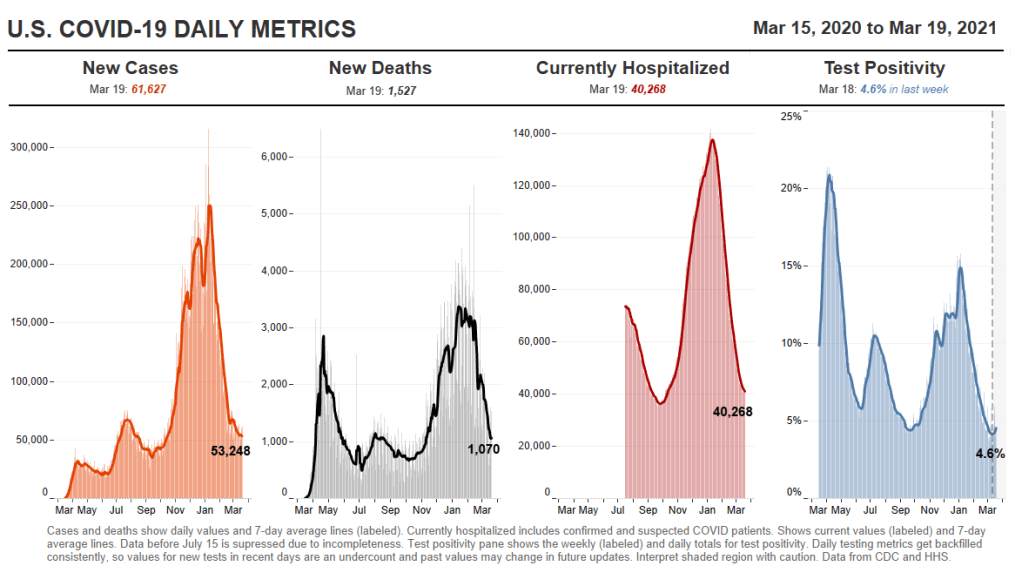

And what we’re now seeing, which is really exciting, is that it’s effective. There’s a great study that just came out of the U.K. about a month ago, showing that for every additional one percent of the population that downloaded the NHS’s COVID-19 app, they saw a reduction in cases of somewhere between 0.8 and 2.3 percent.

BL: Oh, wow.

JW: The more people that adopt the app, it actually has had a material impact on their COVID-19 cases. The estimates overall are as many as 600,000 cases were averted in the U.K. because of this app.

Editor’s note: The study, by researchers at the Alan Turing Institute, was submitted for peer review in February 2021. Read more about the research here.

BL: That goes into something else I was going to ask you, which is this kind-of interesting dynamic between all the code behind the apps being open source, that being very public and accessible, as opposed to the data itself being very anonymized and private—it’s this tradeoff between the public health needs, of we want to use the app and know how well it’s working, versus the privacy concerns.

JW: The decision was made from the beginning, since the models showed higher levels of adoption of these apps was going to be critical in order for them to be successful. The more people you could get opting into it, the better. Because of that, the decision was made to try and design for the lowest common denominator, as it were. To make sure that you’re designing these apps to be as acceptable to as many people as possible, to be as unobjectionable as possible in order to maximize adoption.

With all of that came the privacy-first design. Yes, a lot of people don’t care about the privacy issues, but we were seeing that enough people cared about it that, if we were to launch something that compromised somebody’s privacy, we were going to see blowback in the media and we were going to see all sorts of other issues that tanked the success of the product.

Yes, it would be nice to get as much useful information to public health authorities as possible, but the goal of this was not to supplant contact tracing, but to supplement it. The public health authorities were going to be getting most of the data that we were able to provide via they know who’s tested positive. They’re already getting contact tracing interviews with them. It wasn’t clear what we could deliver to the public health authority system that wasn’t already being gathered some other way.

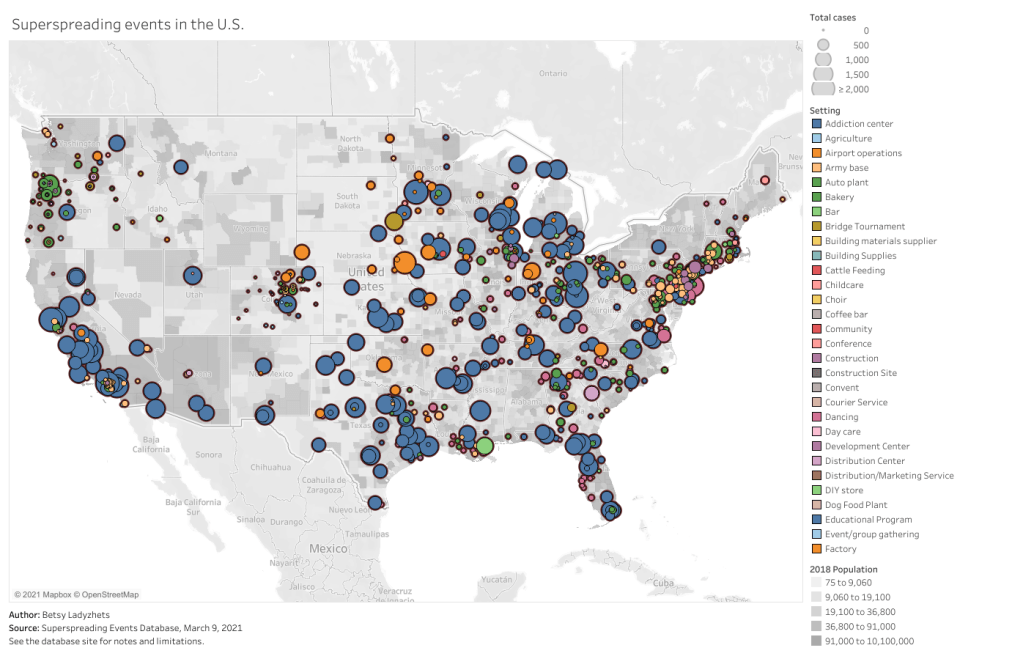

There could’ve been something [another version of the app] where it gave the exposure information, like who you’ve been with, to the public health authority, and allowed them to go and contact those people before the case investigations did. But there were so many additional complications to that beyond just the privacy ones, and that wasn’t what—we weren’t hearing that from the public health authorities. That wasn’t what they needed. They were trying to figure out ways to get people to change behavior.

We really pressed forward with this as a behavior change tool, and to get people into the contact tracing system. We never wanted it to replace the contact tracing that the public health authorities were already spinning up.

BL: I suppose a counter-argument to that, almost, is that in the U.S., contact tracing has been so bad. You have districts that aren’t able to hire the people they need, or you have people who are so concerned with their privacy that they won’t answer the phone from a government official, or what-have-you. Have you seen places where this system is operating in place of contact tracing? Or are there significant differences in how it works in U.S. states as opposed to in the U.K., where their public health system is more standardized.

JW: Obviously, none of us foresaw the degree to which contact tracing was going to be a challenge in the U.S. I think, though, it’s very hard—the degree to which we would’ve had to compromise privacy in order to supplant contact tracing would have been enormous. It’s not like, oh, we could loosen things just a little bit and then it would be a completely useful system. It would have to have been a completely centralized, surveillance-driven system that gave up people’s social graphs to government agencies.

We weren’t designing this, at any point in time, to be exclusively a U.S. program. The goal was to be a global program that any government could use in order to supplement their contact tracing system. And so we didn’t want to build anything that would advance the agenda—we had to think about bad actors from the very beginning. There are plenty of people just in the U.S. who would use these data in a negative way, and we didn’t want to open that can of worms. And if you look at more authoritarian or repressive governments, we didn’t want to allow them a system that we would regret having launched later.

BL: Yeah. Have you seen differences in how European countries have been using it, as compared to the U.S.?

JW: There have been some ways in which it’s been different, which has more to do with attitudes of the citizenry than with government use of the app itself. The NHS [in the U.K.] has a more unique approach.

The U.K. and New Zealand both ended up building out a QR code check-in system, where if you go to a restaurant or a bar… You have a choice, either you write your name and phone number in a ledger that the venue keeps at their front door. So if there’s an outbreak later, they can call you, reach out and do the case investigation. Or you scan a QR code on your phone that allows you to check into that location and figure out where you’re moving. If there’s an alert [of an outbreak] there, you get a notification saying, you were somewhere that saw an outbreak, here’s your next steps.

One of the big advantages of the U.K. choosing to do that is essentially that—every business had to print out a QR code to post at their front door. Something like 800,000 businesses across England and Wales printed out these QR codes. And that means anyone who walks into one of those venues gets an advertisement for their app, every single time they go out. It was very effective in getting good adoption.

We’ve also seen a very big difference in how different populations think about the app and use it. For instance, Finland has had very good compliance with their app. What we mean by that is, if you test positive and you get a code that you need to upload, in Finland, there’s a very high likelihood that you actually go through that process in your exposure notification app. That’s something that I think a lot of jurisdictions have been struggling with in the U.S. and other countries—once you get the code, making sure that somebody actually uploads it.

It makes sense, because getting a positive diagnosis for COVID is a very stressful thing. It’s a very intense moment in your life. And you might not be thinking immediately, “Oh, I should open my app and upload my code!”

BL: Right, that’s not the first thing you think of… This relates to another question I have, which is how you’ve seen either U.S. states or other countries adapting the technology for their needs. You talked about the U.K. and New Zealand, but I’m wondering if there are other examples of specific location changes that have been made.

JW: There have been some mild differences. Like, this app will allow you to see data about how each county is performing in your jurisdiction, so you can also go there to get your COVID dashboard. I’ve seen some apps where, if you get a positive exposure notification, that jumps you to the front of a line for a test. You can schedule a test in the app and you can get a free test as opposed to having to pay for it.

I’ve seen things like that, but overall, at least with the Google/Apple exposure notification system, it’s been small changes to that degree. Where you see more dramatic changes is where countries have built their own system. You can look at something like Singapore, where people who don’t have phones get a dongle that they can use to participate in the system. It’s entirely centralized, and so they are able to do things like, a lot of contact tracing actually from the information they get with the app. There are places where it’s more aggressive in that sense.

For the most part, though, I’d say it’s been pretty consistent… The one-year anniversary of the TCN Coalition isn’t until April 5, but if you think about how far we’ve come from this just being an idea in a couple of people’s heads to, last I heard, the GAIN [Google/Apple] exposure notification apps are on 150 million phones worldwide.

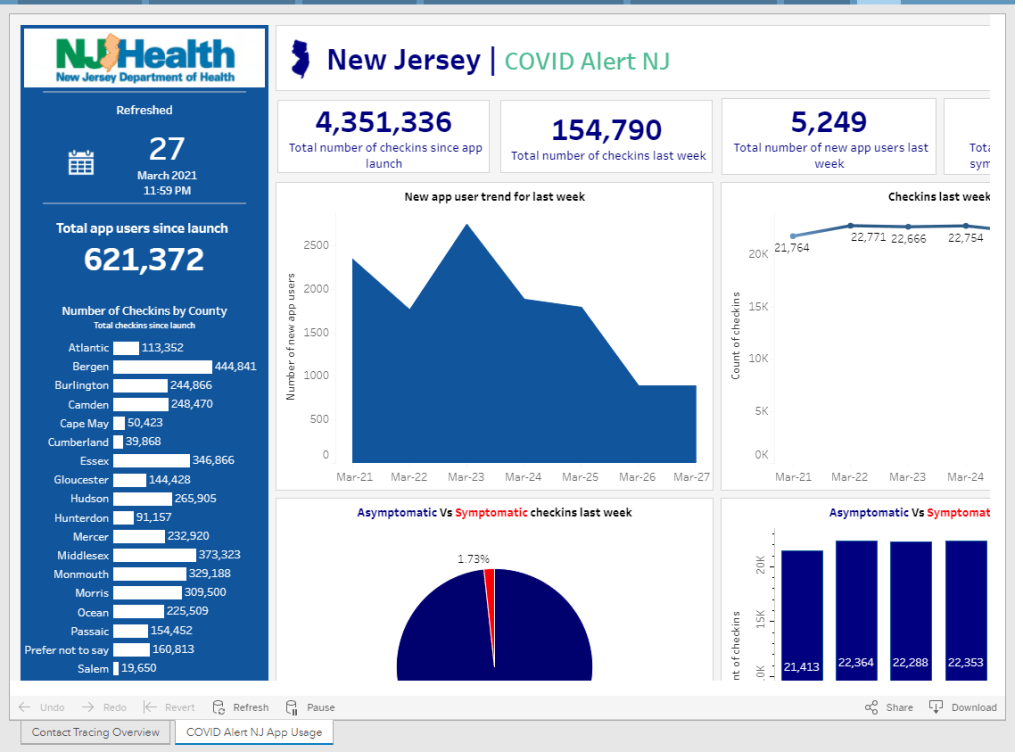

BW: Wow! Is that data publicly available, on say, how many people in a certain country have downloaded apps? I know, one state that I’ve found is publishing their data is New Jersey, they have a contact tracing pane on their dashboard. I was curious if you’d seen that, if you have any thoughts on it, or if there are any other states or countries that are doing something similar.

JW: I wish there was more transparency. Switzerland has a great dashboard on the downloads and utilization of their app. DC, Washington state, also publicly track their downloads. I’m sure a few others do but I don’t know off the top of my head who makes the data public.

I do wish it were the default for everybody to make that data public… There’s a lot of concern by states where there’s not good adoption, that by making the data public they’re opening up a can of worms and are going to get negative press and attention for it, so they don’t want to. So it’s been a mix in that way.

BL: I think part of that is also an equity concern. How do you know that you have a good distribution of the population that’s adopting it, or even that the people who need these apps the most, say essential workers, people of color, low-income communities—how do you know that they’re adopting it when it’s all anonymous?

JW: It’s actually—if you’re going to have low adoption, what’s much more effective is if you have high adoption in a certain community. There is a health equity question, but it’s not necessarily about equal distribution of the app, but rather—and this is where some states have been successful, is that they haven’t gotten high adoption across the board but they’ve decided on a couple of high-need communities that are the ones they’re going to target for getting adoption of the app. They’ve gone after those instead, and that, for many of the states, has been a more effective way to drive use.

BL: I live in New York City, and I know I’ve seen ads for the New York one, like, in the subways and that sort of thing, which I have appreciated.

Is there a specific state or country that you’d consider a particularly successful example of using these apps?

JW: NHS, England and Wales, definitely. I think Ireland has done a pretty good job of it, and Ireland is—we’re particularly fond of them because they were one of the first to open source their code, and make it available. They open-sourced with LFPH to make it available for other countries, and so that is the code that powers the New York app as well. New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and then a couple of other countries globally, including New Zealand. It’s the most used code, besides the exposure notification express system that Apple and Google built for getting these apps out.

I also mentioned Finland before, I think they got the messaging right such that they have very high buy-in on their app.

BL: Are you collecting user feedback, or do you know if various states and countries are doing this, in order to improve the apps as they go?

JW: Usually as a product manager, you’re constantly wanting to improve the UI [user experience] of your app, getting people to open it, and all that. These are interesting apps in that they’re pretty passive. Your only goal is to get people not to delete them. They can run in the background for all of eternity. As long as the phone is on and active, that’s all that’s needed.

BL: As long as you have your Bluetooth turned on, right?

JW: As long as you have your Bluetooth turned on. So the standard for the success of these apps is a completely different beast. We at LFPH have not been monitoring the user feedback on this, but a lot of states and countries are. Most of them have call centers to deal with questions about the app.

Some jurisdictions are improving it, but most improvements are focused on the risk score, which is the settings about how sensitive the app should be.

BL: Like how far apart you need to be standing, or for how long?

JW: Right. How to translate the Bluetooth signal into an estimate of distance, and how likely should it be—how willing are you to send an alert to somebody, telling them that they’ve been exposed, based on your level of confidence about whether they actually were near somebody or not. There’s a decent amount of variance there in terms of how a state thinks about that, but that’s been much more on the technical side, where people are trying to tweak the system, than on the actual app. There have been some language updates to clarify things, to make it easier for people to know what to do next, but it’s not been the core focus of the app designs like it would be if this were a more traditional system.

BL: What does your day-to-day job actually look like, coordinating all of these different systems?

JW: We’re [LFPH/TCN] really an advisor to the jurisdictions. It’s not a coordinating thing but rather, I spend a lot of my time on calls with various states saying, “Here’s what’s happening with the app over in this place, here’s what this person is doing, have you considered this, do you want to talk to that person.” I’m trying to connect people, trying to provide education about how these systems work, and for the states that are still trying to figure out whether to launch or not, convincing them to do it and sharing best practices.

Also, with Linux Foundation Public Health, we’re working on a vaccination credentials project. So I’m splitting my time between those, as well as just running the organization and keeping financials, board relationships, networking, fundraising, keeping all of those things together.

BL: Sounds like a lot of meetings.

JW: It’s a fair number of meetings, this is true.

BL: So, that’s everything I wanted to ask you. Is there anything else you’d like folks to know about the system?

JW: Ultimately, the verdict is, now that we’re seeing it’s effective [from the U.K. study], I think that adds to the impetus to download and use the system. Even before that, though, the verdict was—this is extraordinarily privacy-preserving, there’s no reason not to do it. That continues to be our message. There’s no harm in having this on your phone, it doesn’t take up much battery life, so turn it on!