I recently received a question from a reader, asking how to follow both COVID-19 and the flu in the county where she lives. For COVID-19, county-level data sources aren’t too hard to find: the CDC still provides some clinical data—though case numbers are now updated weekly, instead of daily—and many counties have wastewater surveillance available. (See last week’s post for more details.)

But following flu transmission is much harder: there’s no county-level tracking of this virus. The same thing goes for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a virus currently sending record cases to children’s hospitals across the country. There are a few data sources available, which I’ll list later in this post, though nothing as comprehensive as what we’ve come to expect for COVID-19.

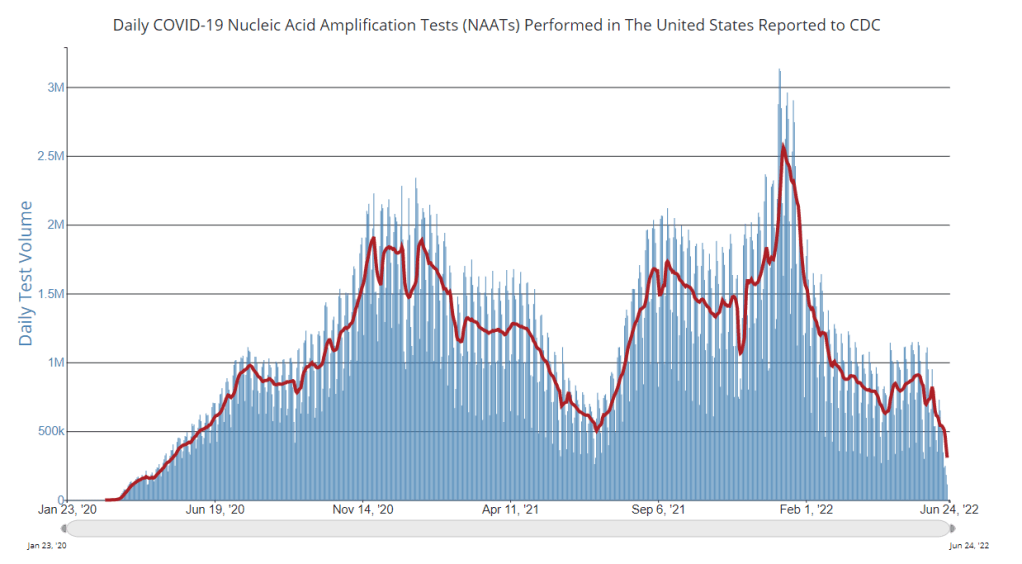

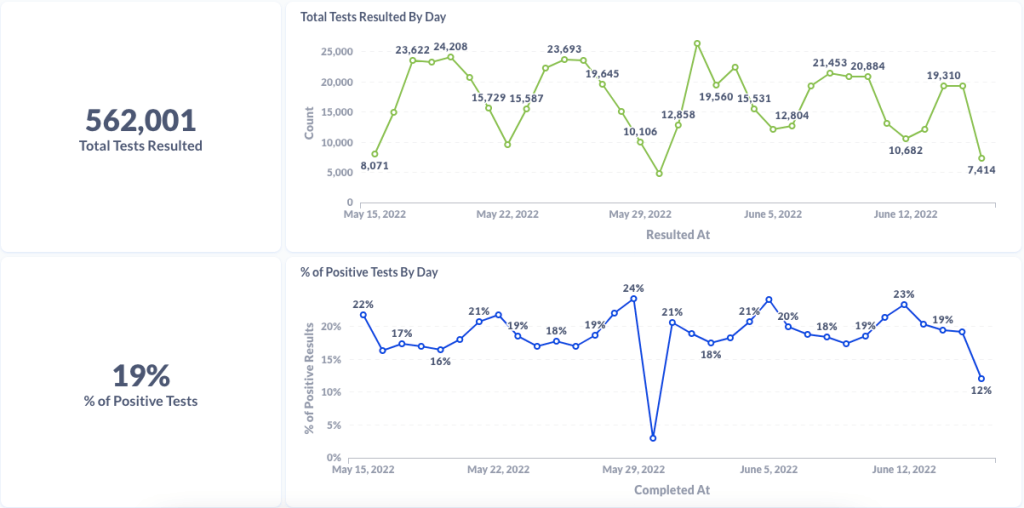

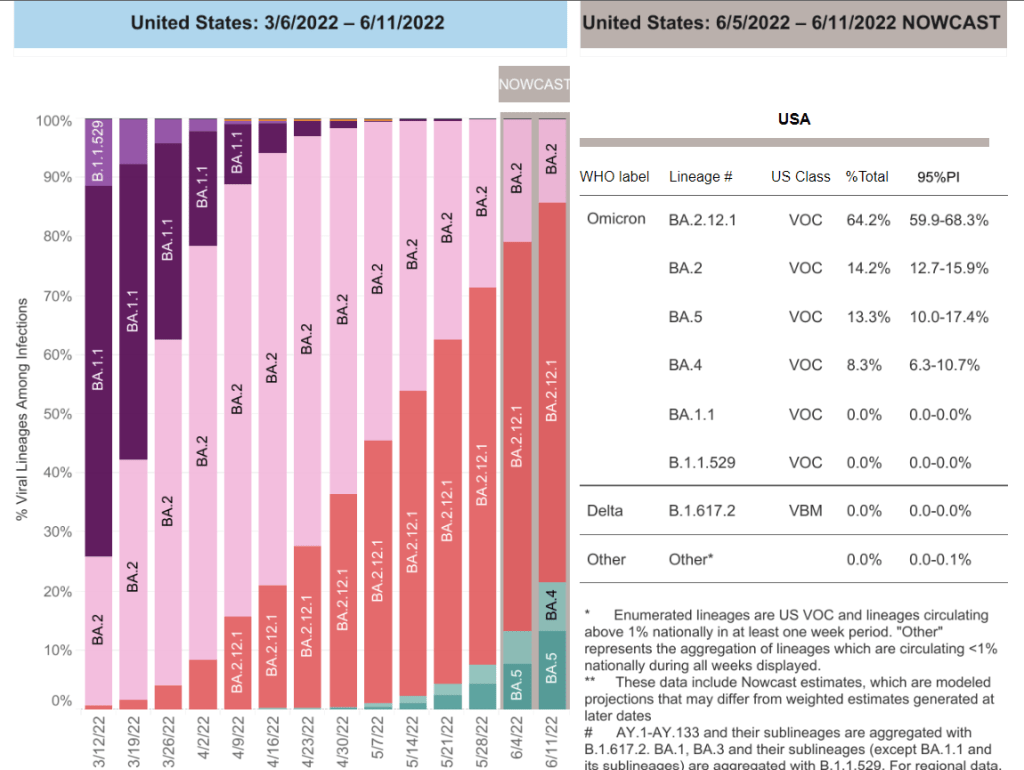

As I’ve previously written, the COVID-19 pandemic inspired nationwide disease surveillance at a level the U.S. has never seen before. The healthcare and public health systems had not previously attempted to count up every case of a widely-spreading virus and share that information back to the public in close-to-real-time.

It’s unlikely that flu, RSV, and other diseases will get the same resources as COVID-19 did for intensive tracking—at least not in the near future. But the scale of data we’ve had during the pandemic reveals that our current surveillance for these diseases is pretty inadequate, even for such basic purposes as giving hospitals advanced warning about new surges.

Insufficient RSV data

A recent CNN story by Deidre McPhillips and Jacqueline Howard explains how data gaps have hindered preparation for the current RSV surge. The reporters explain that the CDC’s RSV data are “based on voluntary reporting from a few dozen labs that represent about a tenth of the population.” The CDC uses these reports to provide weekly estimates about RSV cases, though recent data tend to be incomplete due to reporting delays.

Here’s a helpful quote from the story (though I recommend reading the whole piece):

“For hospitals [using CDC data], it’s a little like looking through the rearview mirror. They’ve already begun to experience that uptick in cases themselves before it’s noticeable in the federal data,” said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality and patient safety with the American Hospital Association.

“We’re talking about data that are collected inside hospitals, transmitted through a data trail to get to the federal government, analyzed there and then fed back to hospitals.”

In other words, it’s not surprising that we saw plenty of stories about higher-than-normal RSV cases in children’s hospitals before national data actually picked up the surge. For more details on why RSV is spreading this fall and how it’s impacting children’s hospitals, I recommend this piece by Jonathan Lambert at Grid.

Insufficient flu data

Meanwhile, this year’s flu season is clearly starting earlier than normal; but current data aren’t able to tell us how severe the season might get or who, exactly, is being hit the hardest. According to the CDC’s flu surveillance report for this week, the agency estimates that the U.S. has seen “at least 880,000 flu illnesses, 6,900 hospitalizations, and 360 deaths from flu” so far this fall.

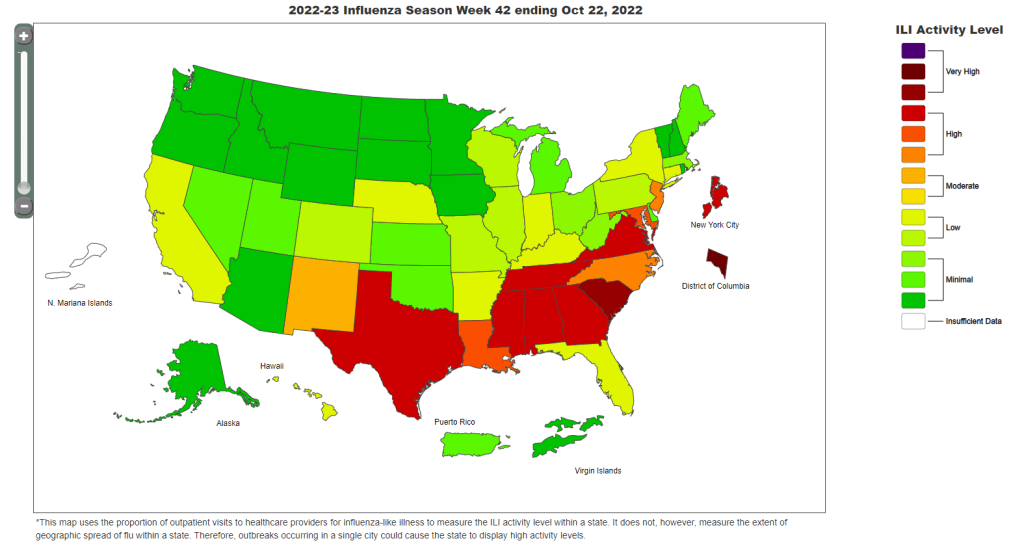

The CDC’s estimates come from networks of testing labs, hospitals, and outpatient healthcare providers that participate in the agency’s flu surveillance networks. National flu data tend to be imprecise estimates, clearly labeled as “preliminary” by the CDC, while state-by-state data are estimates reported with delays. Note, for example, that the CDC’s map of “influenza-like-activity” by state and by metro area provides only general categories of activity (ranging from “minimal” to “very high”) rather than actual case numbers.

The flu data we have so far aren’t sufficient for making predictions about how the rest of this fall and winter will go, explains STAT’s Helen Branswell in a recent story. “The virus is maddeningly unpredictable,” she writes. U.S. experts often look to the flu season in the Southern Hemisphere, which precedes ours, for clues, but this can be unreliable (just as the U.S. shouldn’t rely on other countries for all its vaccine effectiveness data).

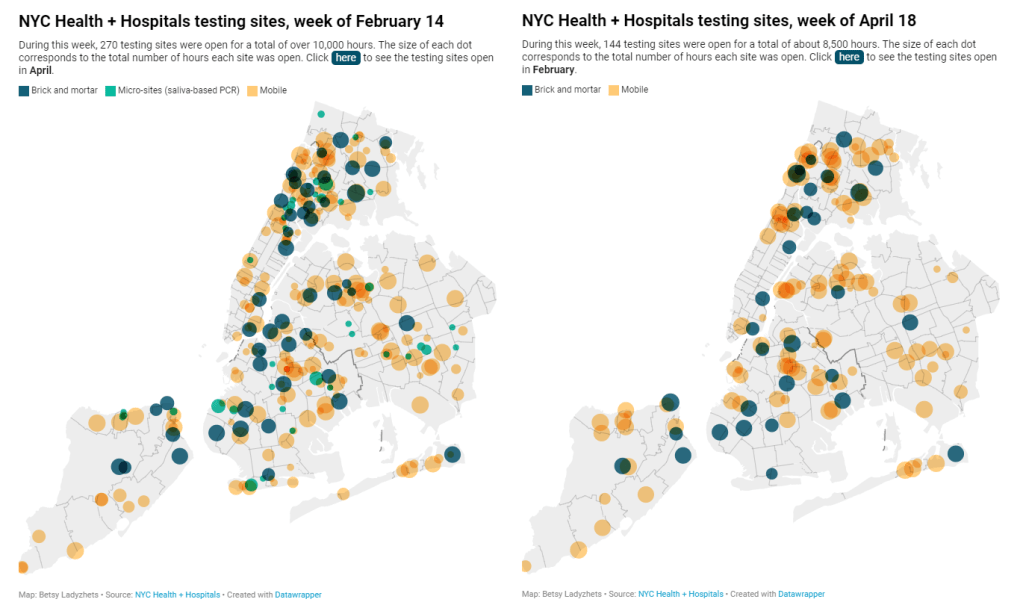

For both flu and RSV, one major problem with our surveillance methods is that our systems overly rely on healthcare centers. When public health agencies have to wait for hospitals and clinics to report cases of these viruses before starting to analyze data, they miss the opportunity to warn healthcare providers at the very beginning of a surge—and give them time to prepare.

In the future, expanding non-clinical surveillance methods like wastewater and population surveys to these diseases would provide more data, more quickly; both for healthcare providers and for the general public. (I provided some more specific ideas here.)

Existing sources

With all the above caveats in mind, here are a few sources you can look at to track flu and RSV:

- CDC’s weekly flu surveillance report: This page is updated once a week with national estimates of flu activity, hospitalizations, flu virus variants, and more. Data tend to be preliminary.

- CDC’s FluView dashboard: Information from the CDC’s flu surveillance system also appears on this dashboard in a more interactive format; for example, you can see how flu activity by state has changed over time.

- CDC’s RSV trends report: Similar to its flu reports, the CDC provides weekly updates of estimated RSV tests and cases, including national, regional, and state-by-state trends.

- Walgreens flu index: Walgreens tracks prescriptions for antiviral medications at its pharmacies as a proxy for flu activity, by state and for select metro areas. For more information on the index, see this press release.

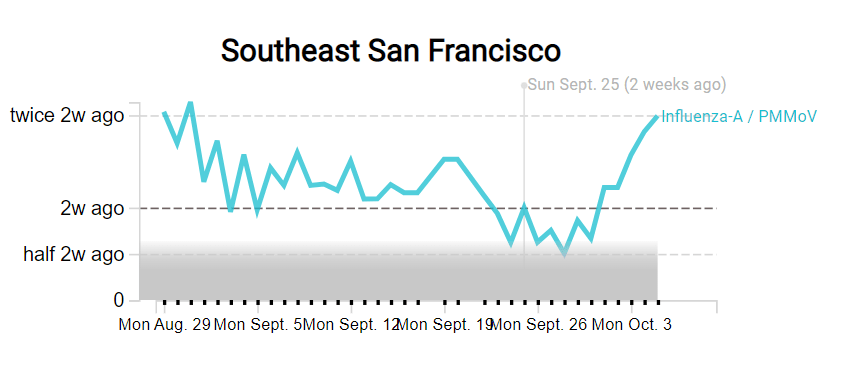

- WastewaterSCAN: The SCAN network, run by researchers at Stanford University and Emory University, tests wastewater for flu, RSV, and monkeypox in addition to COVID-19 in select counties across the U.S. So far, this network is the first I know of to publicly share flu and RSV wastewater data, though other researchers are working in this area.

Please let me know if I missed any data sources! (You can email me or comment below.)