When the public health emergency ends this spring, COVID-19 testing is going to move further in two separate directions: rapid, at-home tests at the individual level, and wastewater testing at the community level.

That was my main takeaway from an online event last Tuesday, hosted by Arizona State University and the State and Territory Alliance for Testing. This event discussed the future of COVID-19 testing following the public health emergency, with speakers including regulatory experts, health officials from state agencies, and executives from diagnostic companies.

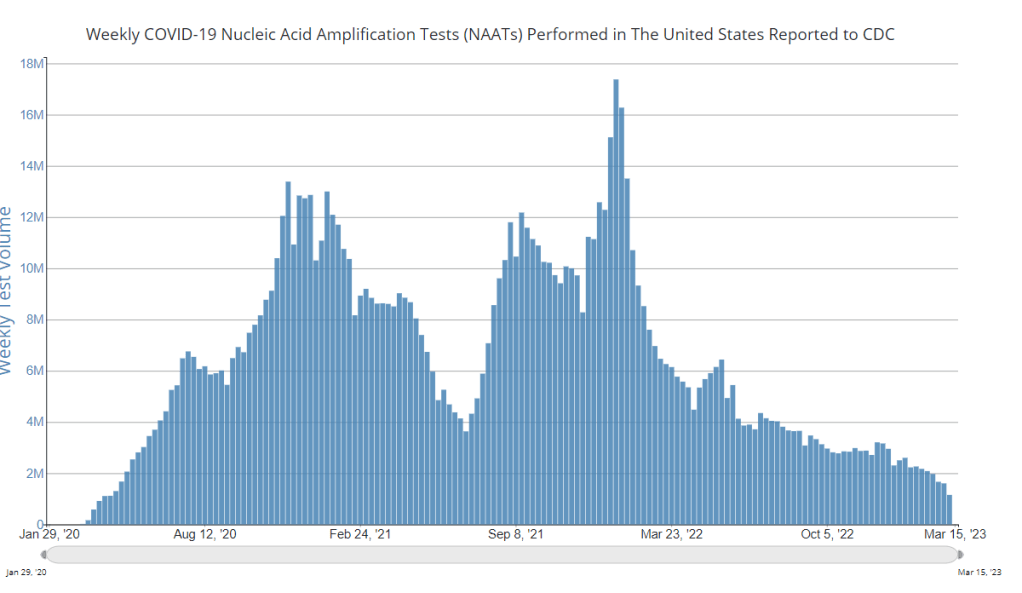

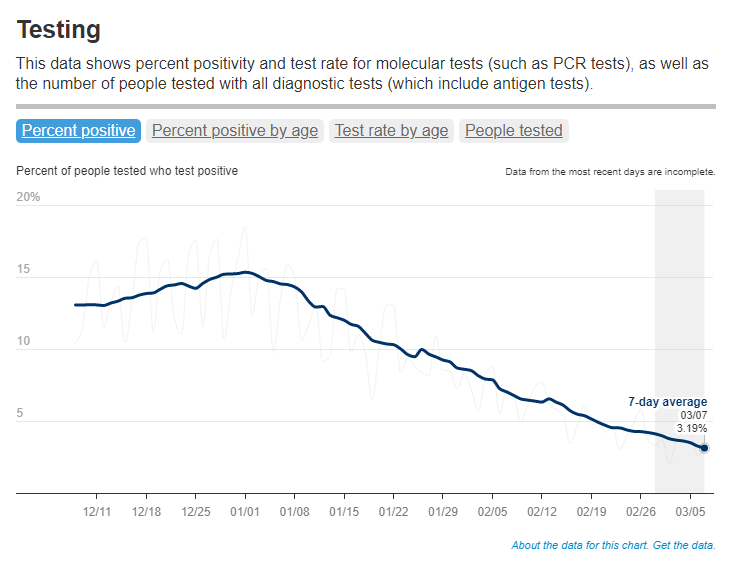

“The purpose of testing has shifted” from earlier in the pandemic, said Dr. Thomas Tsai, the White House’s COVID-19 testing coordinator, in opening remarks at the event. Public health agencies previously used tests to monitor COVID-19 in their communities and direct contact-tracing efforts; now, individual tests are mostly used for diagnosing people, and the resulting data are widely considered to be a major undercount of true cases.

While the speakers largely agreed about the continued value of rapid, at-home tests (for diagnosing people) and wastewater surveillance (for tracking COVID-19), they saw a lot of challenges ahead for both technologies. Here are some challenges that stuck out to me.

Challenges for rapid, at-home tests:

The public health emergency’s end won’t have an immediate impact on which COVID-19 tests are available, health policy researcher Christina Silcox from Duke University explained at the event. But, in the coming months, the FDA is likely to also end its emergency use authorization for COVID-19 diagnostics. As a result, companies that currently have tests authorized under this emergency will need to apply for full approval. Relatively few rapid tests are currently approved in this way, so the change could lead to fewer choices for people buying tests.

At the same time, it will become harder for many Americans to access rapid tests. After the federal emergency ends, private insurance companies will no longer be required to cover rapid tests. Some insurance providers might still do this (especially if large employers encourage it), said Amy Kelbik from McDermott+Consulting, but it will no longer be a universal option. At the same time, Medicare will stop covering rapid tests; Medicaid coverage will continue through fall 2024.

In light of these federal changes, state health officials at the ASU event talked about a need for continued funding to support rapid test distribution from state and local agencies. “Testing will continue to inform behavior, but will become drastically less available,” said Heather Drummond, testing and vaccine program leader at the Washington State Department of Health. Washington has led a free test distribution program, but it’s slated to end with the conclusion of the federal health emergency, Drummond said; she’d like to see services like this continue for the people who most need free tests.

Drummond and other health officials also discussed the challenges of educating people about how to interpret their test results, as COVID-19 guidance becomes less widely available. The vast majority of rapid, at-home test results are not reported to public health agencies—and, based on the event’s speakers, this isn’t a problem health agencies are particularly interested in devoting resources to solving right now. But as rapid tests become the default for diagnosing COVID-19, continued outreach will be needed on how to use them.

Also, as I’ve written before, some PCR testing infrastructure should still be maintained, for cases when someone needs a more definitive test result or wants documentation in case of long-term symptoms. PCR test access will likely get even worse after the federal health emergency ends, though, as insurance plans will also stop covering (or cover fewer costs for) these tests.

Challenges for wastewater surveillance:

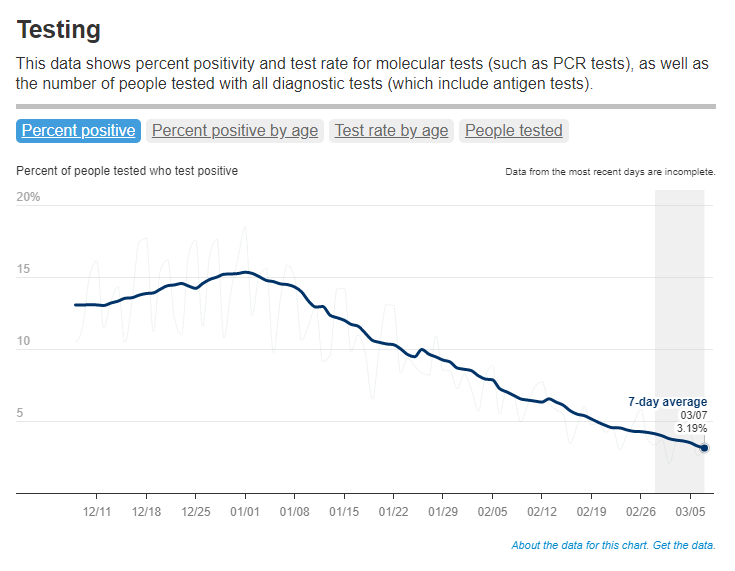

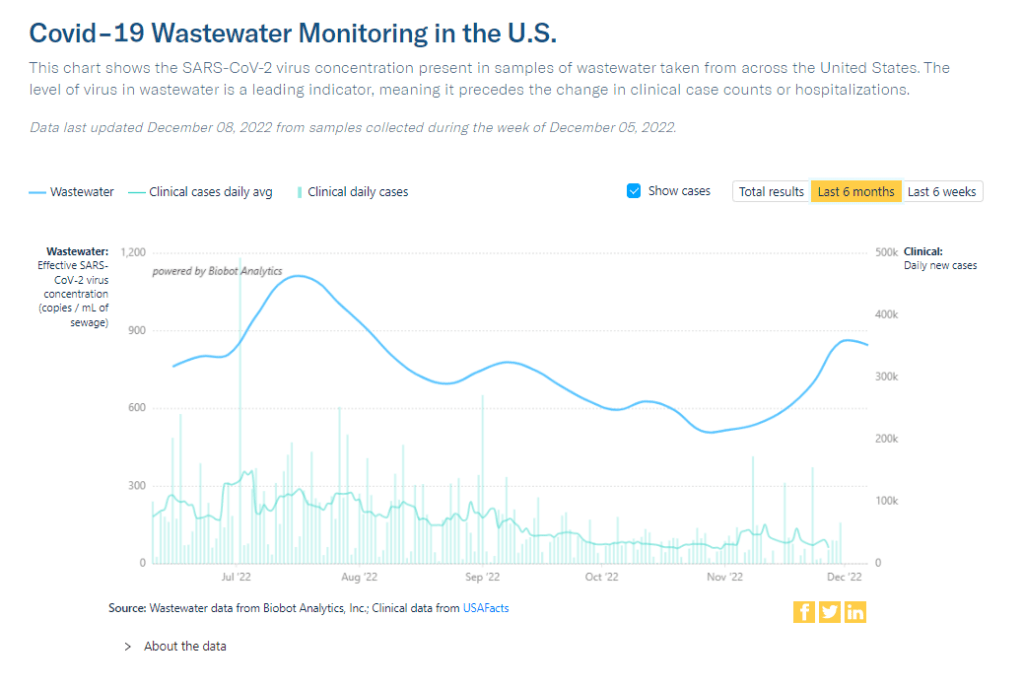

Overall, wastewater surveillance is the best source for community-level COVID-19 data, speakers at the ASU event agreed. Official case numbers represent significant undercounts of true infections, and hospitalizations (while more reliable) are a delayed indicator. Wastewater data are unbiased, real-time, population-level—and the technology can be expanded to other common viruses and health threats, health officials pointed out at the event.

But wastewater surveillance is still very uneven across the U.S. It’s clear just from looking at the CDC’s map that some states have devoted resources to detailed wastewater testing infrastructure, with a testing site in every county—while others just have a handful of sites. Funding uncertainty likely plays a role here; speakers at the event expressed some confusion about the availability of CDC funds for long-term wastewater programs.

The CDC’s wastewater surveillance system has also faced challenges with standardizing data from different testing programs. And, at state and local agencies, health officials are still figuring out how to act on wastewater data. Agencies with more robust surveillance programs (such as Massachusetts, which had two officials speak at the ASU summit) may be able to provide success stories for other agencies that aren’t as far along.

Broader testing challenges:

For diagnostic company leaders who spoke at the event, one major topic was regulatory challenges. Andrew Kobylinski, CEO and co-founder of Primary.Health, said that the FDA’s test requirements prioritize highly accurate tests, even though less sensitive (but easier to use) tests might be more useful in a public health context.

Future COVID-19 tests—and tests for other common diseases—may need a new paradigm of regulatory requirements that focus more on public health use. At the same time, health agencies and diagnostic companies could do more to collect data on how well different test options are actually working. While it’s hard to track at-home tests on a large scale, more targeted studies could help show which tests work best in specific scenarios (such as testing after an exposure to COVID-19, or testing to leave isolation).

Company representatives also talked about financial challenges for developing new tests, particularly as interest in COVID-19 dies down and as recession worries grow this year. While a lot of biotech companies dove into COVID-19 over the last three years, they haven’t always received significant returns on their investments. For example, Lucira, the company behind the first flu-and-COVID-19 at-home test to receive authorization, recently filed for bankruptcy and blamed the long FDA authorization process.

Mara Aspinall, the ASU event’s moderator and a diagnostic expert herself, ended the event by asking speakers whether COVID-19 has led to lasting changes in this industry. The answer was a resounding, “yes!” But bringing lessons from COVID-19 to other diseases and health threats will require a lot of changes—to regulatory processes, funding sources, data collection practices, and more.