Many COVID-19 experts have developed a growing skepticism about “The Morning,” the flagship daily newsletter from the New York Times. David Leonhardt, who writes this newsletter, has pretty limited expertise in science and health reporting, yet he frequently delivers pandemic “explainers” that mislead readers—often by cherry-picking data or suggesting false consensus among experts.

This week, one of Leonhardt’s columns was particularly misleading. Titled “COVID and Race,” the newsletter reported that white Americans are now dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than Black, Latino, and Asian Americans.

But Leonhardt missed one very important factor: age-adjustment. Public health experts frequently adjust morbidity and mortality rates by age in order to account for demographic differences among groups. For COVID-19, this is especially important, because the disease disproportionately impacts older adults—and white Americans generally live longer than people of color because of many other structural health factors.

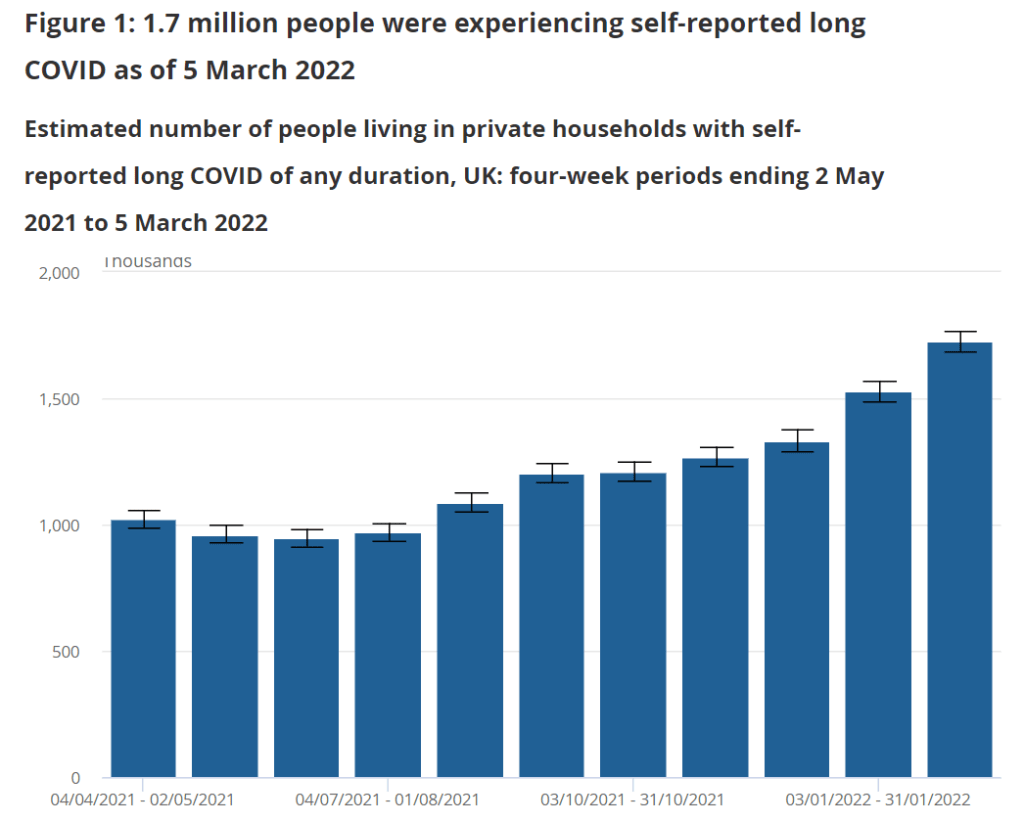

In her Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter, Dr. Katelyn Jetelina further explained why age-adjsutment is important and why this “COVID and Race” column is wrong. When you adjust the death rates by age, Black and Latino Americans are, in fact, still more heavily impacted by COVID-19 deaths than white Americans, though the gap is shrinking.

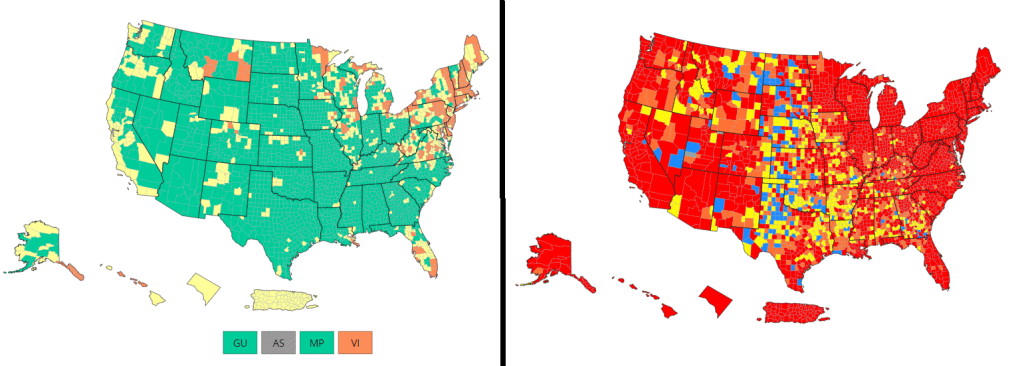

Leonhardt’s newsletter also failed to discuss how COVID-19 has impacted Native Americans. This population has faced the highest death rates throughout the pandemic, according to the CDC and other sources.

It’s important to call out this error, I think, because “The Morning” has a huge reach and can be influential in impacting national pandemic conversations. If we ignore the continued health disparities around COVID-19, we will fail to address them.