Marc Johnson, a molecular virologist and wastewater surveillance expert at the University of Missouri, recently went viral on Twitter with a thread discussing his team’s investigation into a cryptic SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Ohio. I was glad to see the project get some attention, because I find Johnson’s research in this area fascinating and valuable for better understanding the links between coronavirus infection and chronic symptoms.

A “cryptic lineage” is a technical term for, basically, a strange viral mutation that researchers have identified in a specific location. Unlike common variants that spread through the population (Delta, Omicron, BA.5, XBB, etc.), these lineages typically are contained in one place, or even in one person. They’re usually identified by wastewater surveillance, since that technique picks up more people’s infections than testing at doctors’ offices.

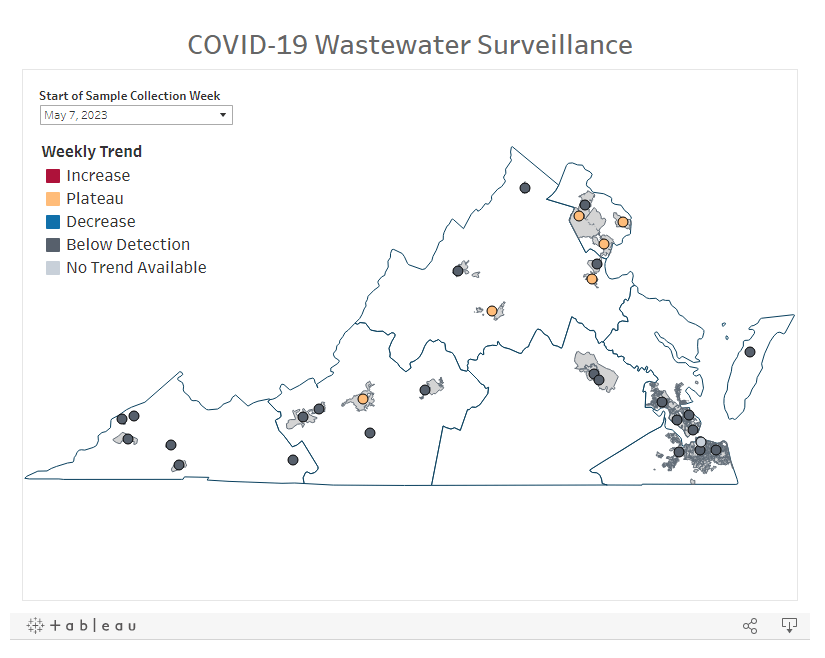

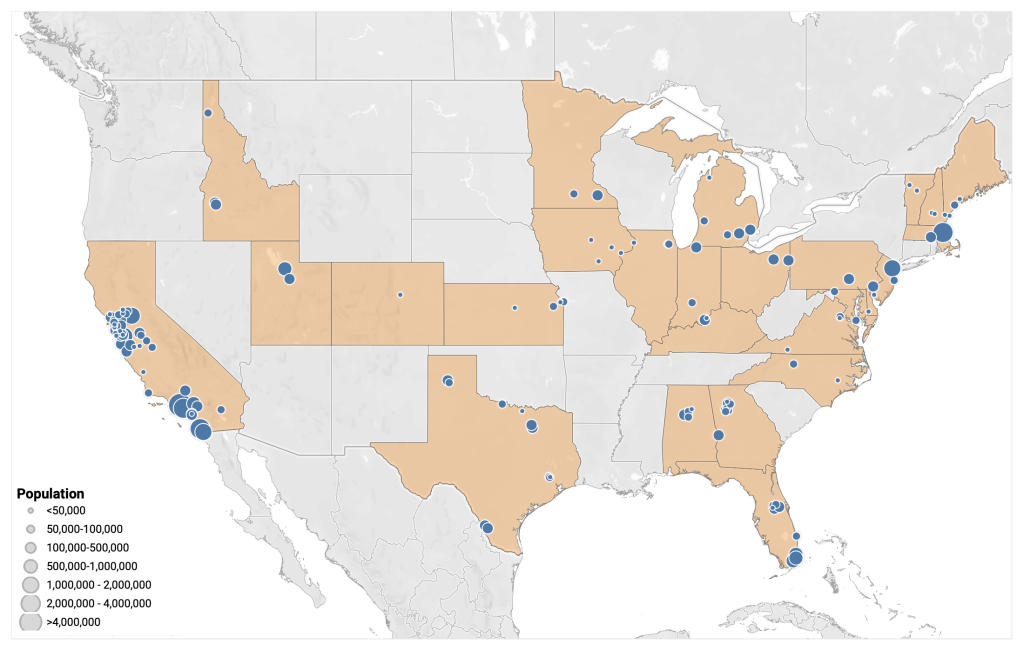

Johnson has become a specialist in investigating these cryptic lineages over the last couple of years. His lab at the University of Missouri runs the state’s wastewater surveillance program, which includes genetic sequencing for sewage samples. And his team also collaborates on sequencing research for wastewater surveillance in other parts of the U.S. This Nature article from last year goes into more detail about how these investigations work.

In the last few months, Johnson and his colleagues have been investigating one cryptic lineage in Ohio. The scientists have traced the lineage to Columbus and a town called Washington Court House; they believe it represents one sick person, who lives in Columbus and goes to Washington Court House for work. This individual is shedding a massive amount of coronavirus, orders of magnitude higher than the average COVID-positive person. See more details in this story by The Columbus Dispatch.

Johnson and his colleagues would like to identify the person behind this lineage for two reasons. First, they can connect the person with doctors who can help treat their COVID-19 symptoms—it’s likely they’re having a pretty nasty gastrointestinal experience. Second, the scientists hope to better understand how viral particles that shed from a long-term infection might be related to chronic symptoms, as persistent virus in different organ systems is one of the leading hypotheses for why Long COVID occurs.

I’ve interviewed Johnson before for stories about wastewater surveillance and I think he does fascinating work, so I was glad to see his Twitter thread get some attention. If you can help identify the Ohio resident with lots of coronavirus in their gut, get in touch with him!