When the University of California at San Diego started planning out their campus reopening strategy last spring, a research team at the school enlisted Ravi Goyal to help determine the most crucial mitigation measures. Goyal is a statistician at the policy research organization Mathematica (no, not the software system). I spoke to Goyal this week about the challenges of modeling COVID-19, the patterns he saw at UC San Diego, and how this pandemic may impact the future of infectious disease modeling.

Several of the questions I asked Goyal were informed by my Science News feature discussing COVID-19 on campus. Last month, I published one of my interviews from that feature: a conversation with Pardis Sabeti, a computational geneticist who worked on COVID-19 mitigation strategies for higher education. If you missed that piece, you can find it here.

In our interview, Goyal focused on the uncertainty inherent in pandemic modeling. Unlike his previous work modeling HIV outbreaks, he says, he found COVID-19 patterns incredibly difficult to predict because we have so little historical data on the virus—and what data we do have are deeply flawed. (For context on those data problems, read Rob Meyer and Alexis Madrigal in The Atlantic.)

Paradoxically, this discussion of uncertainty made me value his work more. I’ve said before that one of the most trustworthy markers of a dataset is a public acknowledgment of the data’s flaws; similarly, one of the most trustworthy markers of a scientific expert is their ability to admit where they don’t know something.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: I’d love to hear how the partnership happened between the university and Mathematica, and what the background is on putting this model together, and then putting it into practice there.

Ravi Goyal: Yeah, I can give a little bit of background on the partnership. When I did my PhD, it was actually with Victor De Gruttola [co-author on the paper]. We started using agent-based models back in 2008 to sort of understand and design studies around HIV. And in particular in Botswana, for the Botswana Combination Prevention Project, which is a large random cluster study in Botswana.

So we started using these kinds of [models] to understand, what’s the effect of the interventions? How big of a study has to be rolled out to answer epidemiological questions? Because, as you would imagine, HIV programs are very expensive to roll out, and you want to make sure that they answer questions.

I’ve been working with [De Gruttola] on different kinds of HIV interventions for the last decade, plus. And he has a joint appointment at Harvard University, where I did my studies, and at the University of California in San Diego. And so when the pandemic happened, he thought some of the approaches and some of the stuff that we’ve worked on would be very applicable to helping think about how San Diego can open. He connected me with Natasha Martin, who is also on the paper and who is part of UC San Diego’s Return to Learn program, on coming up with a holistic way of operating procedures there. She’s obviously part of a larger team there, but that’s sort of where the partnership came about.

BL. Nice. What would you say were the most important conclusions that you brought from that past HIV research into now doing COVID modeling?

RG: Two things. One is uncertainty. There’s a lot of things that we don’t know. And it’s very hard to get that information when you’re looking at infectious diseases—in HIV, in particular, what was very difficult is getting really good data on contacts. In that setting, it’s going to be sexual contacts. And what I have understood is that people do not love revealing that information. When you do surveys where you get that [sexual contact] information, there’s a lot of biases that creep in, and there’s a lot of missing data.

Moving that to the COVID context, that is now different. Different kinds of uncertainty. Biases may be recall biases, people don’t always know how many people they have interacted with. We don’t have a good mechanism to sort of understand, how many people do interact in a given day? What does that look like?

And then, maybe some of these that can creep in when you’re looking at this, is that people may not be completely honest in their different risks. How well are they wearing masks? How well are they adhering to some of those distancing protocols? I think there’s some stigma to adhering or not to adhering. Those are biases that people bring in [to a survey].

BL: Yeah, that is actually something I was going to ask you about, because I know one of the big challenges with COVID and modeling is that the underlying data are so challenging and can be very unreliable, whether that’s, you know, you’re missing asymptomatic cases or it’s matching up the dates from case numbers to test numbers, or whatever the case may be. They’re just a lot of possible pitfalls there. How did you address that in your work with the University of California?

RG: At least with the modeling, it makes it a little more difficult in the timeframe that we were modeling and looking at opening, both for our work on K-12 and for UCSD. We kicked it off back in April, and May, thinking about opening in the fall. So, the issue there is, what does it look like in the fall? And we can’t really rely on—like, the university was shut down. There’s not data on who’s contacting who, or how many cases are happening. There were a lot of things that were just completely unknown, we’re living in a little bit of a changing landscape.

I’m sure other people have much more nuance [on this issue], but I’m going to just broadly stroke where this COVID research was different than HIV. For HIV, people might not radically change the number of partnerships that they’re having. When we’re thinking about a study in Botswana, we can say, what did it look like in terms of incidents four years prior? And make sure we’re making our modeling represents that state of how many infections we think are happening.

Here [with COVID], when we’re thinking about making decisions in September or October. You don’t have that, like, oh, let’s match it to historical data option because there was no historical data to pin it to. So it was pooling across a lot—getting the estimates to run to the model, getting those is, you’re taking a study from some country X, and then you’re taking another different study from country Y, and trying to get everything to work and then hopefully when things open up, you sort-of re-look at the numbers and then iteratively go, what numbers did I get wrong? Now in the setting where things are open, what did we get wrong and what do we need to tweak?

BL: I noticed that the opening kind-of happened in stages, starting with people who were already on campus in the spring and then expanding. So, how did you adjust the model as you were going through those different progressions?

RG: Some assumptions were incorrect in the beginning. For example, how many people were going to live off campus, that was correct. But how many people, of those off-campus people, were ever going to come to campus, was not there. A lot of people decided not to return to San Diego. They were off-campus remote, but they never entered campus. Should they have been part of that model? No. So once we had those numbers, we actually adjusted.

Just this past week, we’ve sort of started redoing some of the simulations to look towards the next terms. Our past miscalculation or misinformation, what we thought about how many people would be on campus, now we adjusted from looking at the data.

And some of the things that we thought were going to be higher risk, at least originally, ended up being a little bit lower risk than anticipated. One thing is around classrooms. There have been—at least, from my understanding, there have been very few transmissions that are classroom-related. And we thought that was going to be a more of a higher transmission environment in the model, wasn’t what we saw when we actually had cases. So now we’re adjusting some of those numbers to get it right to their particular situation. It’s a bit iterative as things unroll.

BL: Where did you find that most transmissions were happening? If it’s not in the classroom, was it community spread coming into the university?

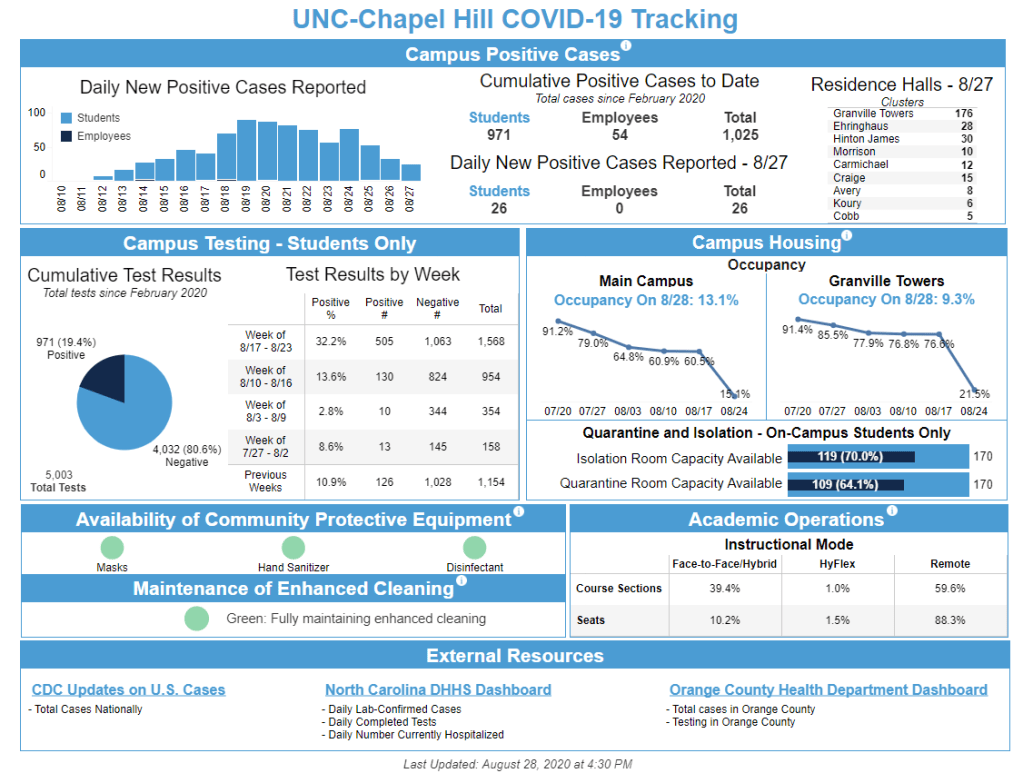

RG: They [the university] have a really nice dashboard, where it does give some of those numbers, and a lot of the spread is coming from the community coming on to campus, and less actual transmissions that are happening within. I think that’s where the bulk is. I think the rates on campus were lower than the outside.

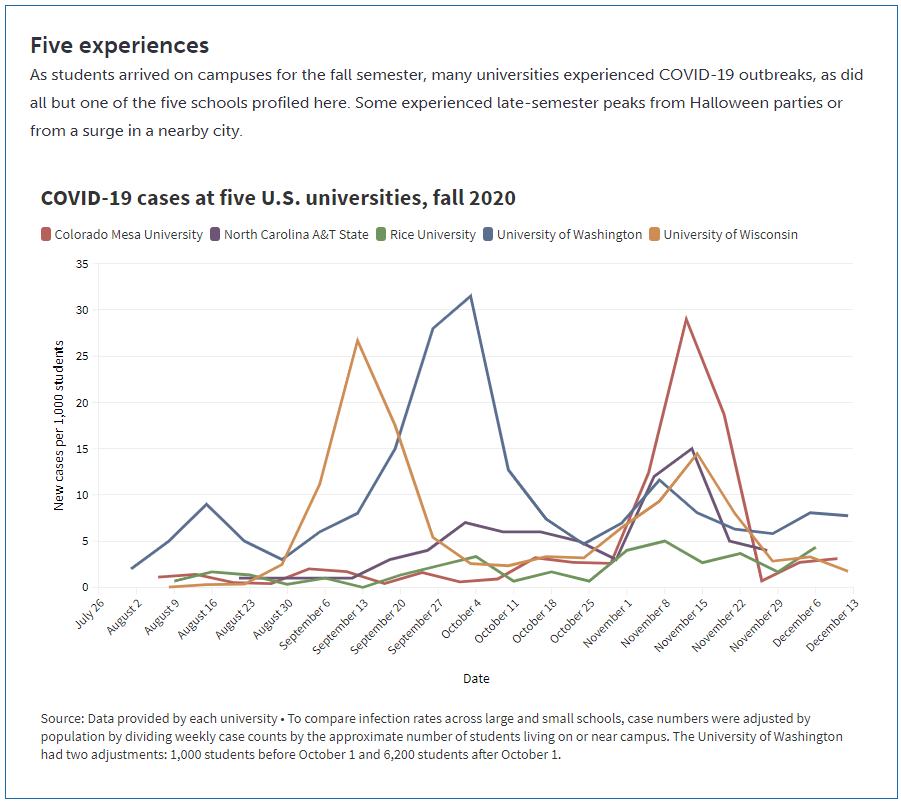

BL: Yeah, that kind-of lines up with what I’ve seen from other schools that I’ve researched that, you know, as much as you might think a college is an environment where a lot of spread’s gonna happen, it also allows for more control, as opposed to just a city where people might be coming in and out.

Although one thing, another thing I wanted to ask you about, is this idea that colleges, when they’re doing testing or other mitigation methods, they need to be engaging with the community. Like UC Davis, there’s been some press about how they offer testing and quarantine housing for everybody. Not just people who are students and staff. I was wondering if this is something accounted for in your model, and sort of the level of community transmission or the level of community testing that might be tied to the university and how that impacts the progression of things on campus.

RG: The model does incorporate these infections coming in for this community rate, and that was actually based off of a different model modeling group, which includes Natasha, that is forecasting for the county [around UC San Diego]. Once again, you have to think about all the biases on who gets tested. False positives, all of those kinds of caveats. They built a model around that, which fed into the agent-based modeling that we use. We do this kind-of forecasting on how many infections do we think are going to be coming in from people who live off-campus, or staff, or family—what’s their risk?

That’s where that kind of information was. In terms of quarantining my understanding is, I don’t think they were quarantining people who weren’t associated [with the school] in the quarantine housing.

BL: Right. Another thing I wanted to ask about, I noticed one of the results was that the frequency of testing doesn’t make a huge difference in mitigation compared to other strategies as long as you do have some frequency. But I was wondering how the test type plays in. Say, if you’re using PCR tests as opposed to antigen tests or another rapid test. How can that impact the success of the surveillance mechanism?

RG: Yeah, we looked a little bit in degrading the sensitivity from a PCR test to antigen. The conclusion was that it’s better to more frequently test, even with a worse-performing test than it is to just do monthly on the PCR.

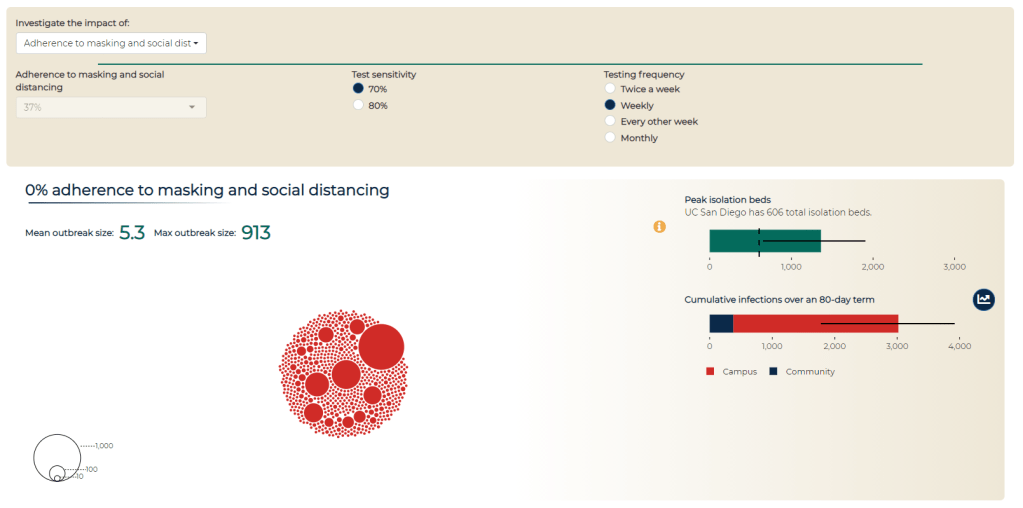

We put it on the dashboard. This is the modeling dashboard… It has a couple of different purposes. So first, there was obviously when the campus was opening, a lot of particular anxiety on what may happen come September, October, and some of that [incentive behind the dashboard] was to be transparent. Like, here’s the decisions being made, and here is some of the modeling work… Everything that we know or have is available to everyone.

And the second piece was to have a communication that safety on campus is the responsibility of everyone. That’s where the social distancing and adherence to masking comes in, why you’re allowed to change that [on the dashboard], is supposed to hopefully indicate that, you know, this really matters. Here’s where the students and faculty and staff roles are on keeping campus open. That was the two points, at least on my end, in putting together a dashboard and that kind of communication.

BL (looking at the modeling dashboard): It’s useful that you can look at the impacts of different strategies and say, okay, if we all wear masks versus if only some of us wear masks, how does that change campus safety?

Another question: we know that university dorms, in particular, are communal living facilities—a lot of people living together. And so I was wondering what applications this work might have for other communal living facilities, like prisons, detention centers, nursing homes. Although I know nursing homes are less of a concern now that a lot of folks are vaccinated there. But there are other places that might not have the resources to do this kind of modeling, but may still share some similarities.

RG: Yeah, I think that’s a really interesting question. I sit here in Colorado. The state here runs some nursing homes. So we originally looked at some of those [modeling] questions, thinking about, can we model [disease spread in nursing homes]?

I think there’s some complexities there, thinking about human behavior, which may be a little bit easier in a dorm. The dorm has a sort-of structure of having people in this suite, and then within the dorm—who resides there, who visits there, has some structure. It’s a little bit harder in terms of nursing homes, or probably it’s the same with detention centers, in that you might have faculty or staff moving across a lot of that facility, and how that movement is a constantly-evolving process. It wasn’t like a stationary state, having a structure, if that makes sense?

BL: Yeah. Did you have success in modeling that [nursing homes]?

RG: Not really so much with [a long-term model], it was more, we had a couple of meetings early on, providing guidance. My wife works for the state with their COVID response, so that was an informal kind-of work. They were trying to set up things and think about it, so I met with them to share some lessons learned that we have.

BL: That makes sense. What were the main lessons? And I think that is a question, returning to your university work, as well—for my readers who have not read through your paper, what would you say the main takeaways are?

RG: I think I would probably take away two things that are a little bit competing. One is, based on both some of the university work and the K-12 work, that we have the ability to open. We have a lot of the tools there, and some things can open up safely given that these protocols that we have in place, particularly around masking and stuff like that, can be very effective. Even in settings that I would have originally thought were very high risk. Areas that could have a very rapid spread, for example college campuses.

Some campuses, clearly, in the news, [did have rapid spread]. But it’s possible to open safely. And I think some of the positive numbers around UC San Diego showed that. Their case counts were very manageable for us. It was possible to open up safely, and same with the K-12. That requires having a first grader wear a mask all day, and I wasn’t sure it would work! But it seems like some of that takeaway is that these mitigation strategies can work. They can work in these very areas that we would have not thought they would have been successful.

So that’s one takeaway, that they can work. And the competing side is that there’s a lot of uncertainty. Even if you do everything right, there is a good amount of uncertainty that can happen. There’s a lot of luck of the draw, in terms of, if you’re a K-12 school, are you going to have just a couple people coming in that could cause an outbreak? That doesn’t mean that you did anything wrong. [There’s not any strategy] that’s 100% guaranteed that, if you run the course, you won’t get any outbreaks.

BL: I did notice that the paper talks about superspreading events a little bit, and how that’s something that’s really difficult to account for.

RG: Human behavior is the worst. It’s tough to account for, like, are there going to be off-campus parties? How do you think about that? Or is that, will the community and their communication structure going to hamper that and effectively convince people that these safety measures are there for a reason? That’s a tricky thing.

BL: Did you see any aspect of disciplinary measures whether that is, like, students who had a party and then they had to have some consequence for that, or more of a positive affirmation thing? One thing that I saw a couple of schools I’ve looked at is, instituting a student ambassador program, where you have kids who are public health mini-experts for their communities, and they tell everyone, make sure you’re wearing your masks! and all that stuff. I was wondering if you saw anything like that and how that might have an impact.

RG: The two things that I know about… I know there were alerts that went out, like, oh, you’re supposed to be tested every week. I don’t know about any disciplinary actions, that’s definitely out of my purview. But talking to grad students as well, I knew that if they didn’t get tested in time, they would get an alert.

And the other thing that I will say in terms of the planning process—I got to be a fly on the wall in UC San Diego’s planning process on opening up. And what I thought was very nice, and I didn’t see this in other settings, is that they actually had a student representative there, hearing all the information, hearing the presentations. I had no idea who all of these people are on all these meetings, but I know there was a student who voiced a lot of concerns, and who everyone seemed to very much listen to and engage with. It was a good way to make sure the students aren’t getting pushed under—a representative was at the table.

BL: Yeah, absolutely. From the student perspective, it’s easier to agree to something when you know that some kind of representative of your interest has been there, as opposed to the administrators just saying, we decided this, here’s what you need to do now.

My last question is, if you’ve seen any significant changes for this current semester or their next one. And how vaccines play into that, if at all.

RG: That’s the actual next set of questions that we’re looking into. If weekly testing continues, does the testing need change as people get vaccinated? The other thing that they have implemented is wastewater testing and alerts. They’re sampling all the dorms. And how does that impact individual testing, as well? Does that—can you rely on [wastewater] and do less individual testing? That’s some of the current work that we’re looking into.

BL: That was all my questions. Is there anything else that you’d want to share about the work?

RG: I will say, on [UC San Diego’s] end… I think you can use models for two things. You can use them to make decisions—or not make them, but help guide potential decisions. Or you can use them to backdate the decisions that you wanted to make. You can always tweak it. And I would say, in the work I’ve done, it’s been the former on the part of the school.

The other thing is, thinking about the role of modeling in general as we move forward, because I think there’s definitely been an explosion there.

BL: Oh, yeah.

RG: I think it brought to light the importance of thinking about… A lot of our statistical models, for example, are very much individual-based. Like, your outcome doesn’t impact others. And I can see these ideas, coming from COVID—this idea that what happens to you impacts me, it’s going to be a powerful concept going forward.