Last week, Janssen, a pharmaceutical division owned by megacorp Johnson & Johnson, released results for its phase 3 ENSEMBLE study. The Janssen vaccine uses an adenovirus vector (a modified common cold virus that delivers the DNA necessary to make the coronavirus spike protein), can be stored at normal fridge temperatures, and only requires one dose. Here’s a table of the raw numbers from Dr. Akiko Iwasaki of Yale:

At first glance it does look like it’s “less effective” than the mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer. But, when you look at the severe disease, there’s a 100% decrease in deaths. No one who got the J&J vaccine died of coronavirus, no matter where they lived— including people who definitely were diagnosed with the South African B.1.351 variant. Here’s how that compares with the Moderna, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Novavax vaccines, per Dr. Ashish Jha of Brown:

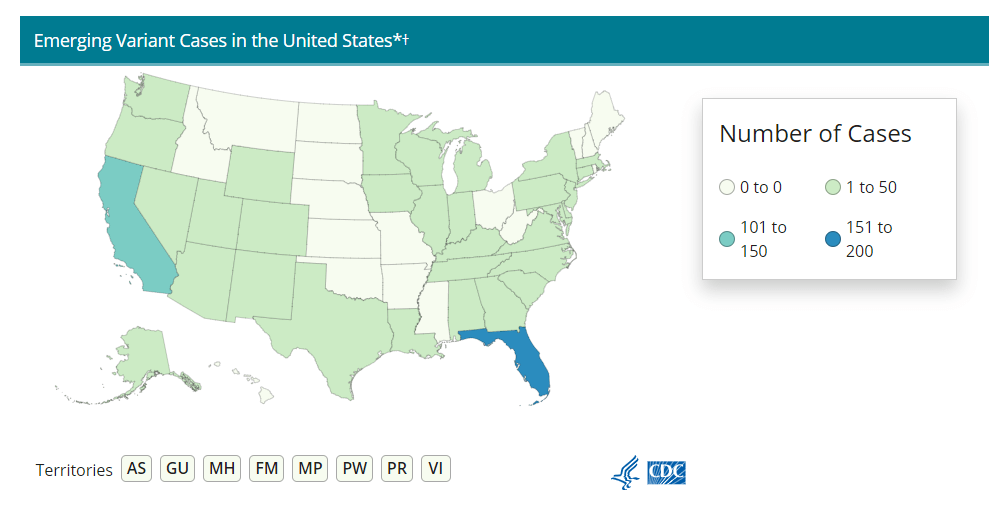

Nobody who got any of the vaccine candidates was hospitalized or died from COVID-19. That’s huge, especially as variants continue to spread across the U.S. (Here’s the updated CDC variant tracker.)

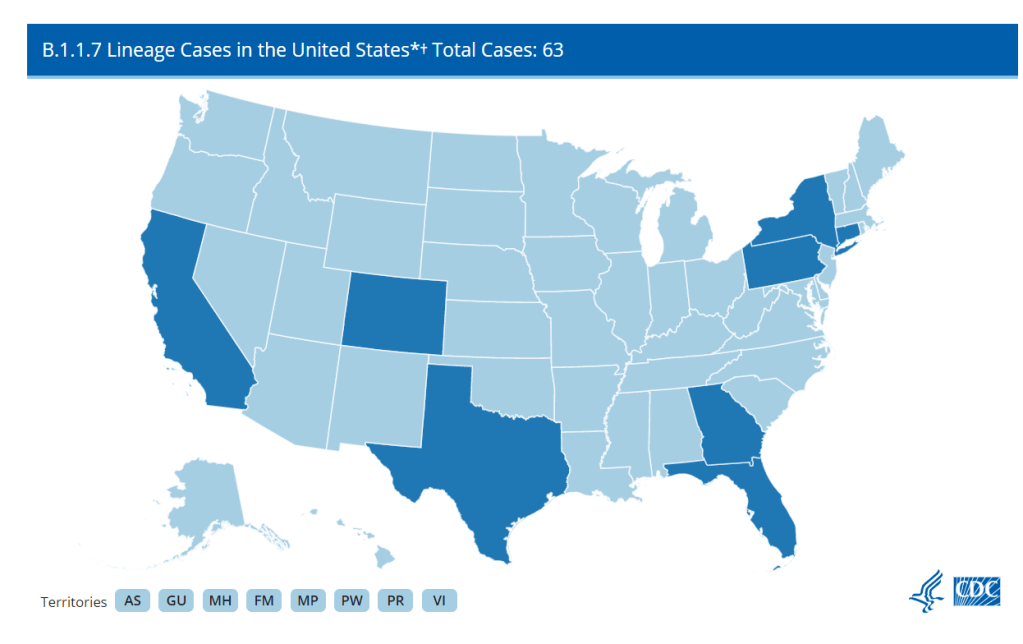

J&J’s numbers are especially promising when it comes to variant strains. Moderna and Pfizer released their results before the B.1.1.7 (U.K.) or B.1.351. (S.A.) variants reached their current notoriety, which makes J&J’s overall efficacy numbers look worse by comparison. But the fact that no one who got the J&J vaccine was hospitalized no matter which variant they were infected with is a cause for optimism. (B.1.351 is the variant raising alarms for possibly being able to circumvent a vaccine’s protection due to a helpful mutation called E484K. A Brazilian variant, P1, also has this mutation, though there’s not a lot of research on vaccine efficacy for this particular mutant.)

It also means that vaccination needs to step up. While it may seem counterintuitive to step up vaccinations against variants that can supposedly circumvent them, it’s important to note that there still was a significant decrease in COVID-19 cases in vaccinated patients from South Africa. A 57% drop compared with the 95% prevalence of the B.1.351 still suggests that vaccination can prevent these cases, and thus can seriously slow the spread of the variant.

What does all of this mean for COVID-19 rates? We can infer a few things. For starters, when vaccines are distributed to the general public around April or May, we may see hospitalization rates and death rates drop more than positive test rates. Positive test rates should obviously drop too, but they’ll probably stay at least a little higher than hospitalizations and death rates for a while.

Second, it means that we really need to ramp up sequencing efforts in the U.S.. We need more data to tell us just how well these vaccines can protect against the spreading variants, but we can’t collect that data if we don’t know which strain of SARS-CoV-2 someone gets. We here at the CDD have covered sequencing efforts – or lack thereof – before, but the rollout has still been painfully slow. CDC Director Rochelle Walensky stressed that “we should be treating every case as if it’s a variant during this pandemic right now,” during the January 29 White House coronavirus press briefing. But the 6,000 sequences per week she’s pushing for as of the February 1 briefing should have been the benchmark months ago. We’re still largely flying blind until we can get our act together.

Some states in particular may be flying blinder than others. As Caroline Chen wrote in ProPublica yesterday, governors of New York, Michigan, Massachusetts, California, and Idaho are planning to relax more restrictions, including those on indoor dining. Such a plan is probably the perfect way to ensure these variants spread, so much that even Chen was surprised at how pessimistic the outlook was when she asked 10 scientists for the piece.

The B.1.1.7 variant is expected to become the dominant strain in the U.S. by March, according to the CDC. And on top of that, the B.1.1.7 variant seems to have picked up that helpful E484K mutation in some cases as well. Per Angela Rasmussen of Georgetown University, if these governors don’t realize how much they’re about to screw everything up, “the worst could be yet to come.” God help us.