The White House has launched a new office focused on high-level pandemic preparedness, about six months after Congress requested this. The new Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy will be a permanent office in the executive branch, according to a fact sheet from the Biden administration.

This announcement is good news; it’s a small step towards improving the U.S.’s infrastructure for responding to future disease threats. But we shouldn’t just be focusing on pandemic preparedness—the U.S. also needs better infrastructure for many health issues impacting the country now, including the continued impacts of COVID-19.

According to the White House, the new office’s responsibilities include:

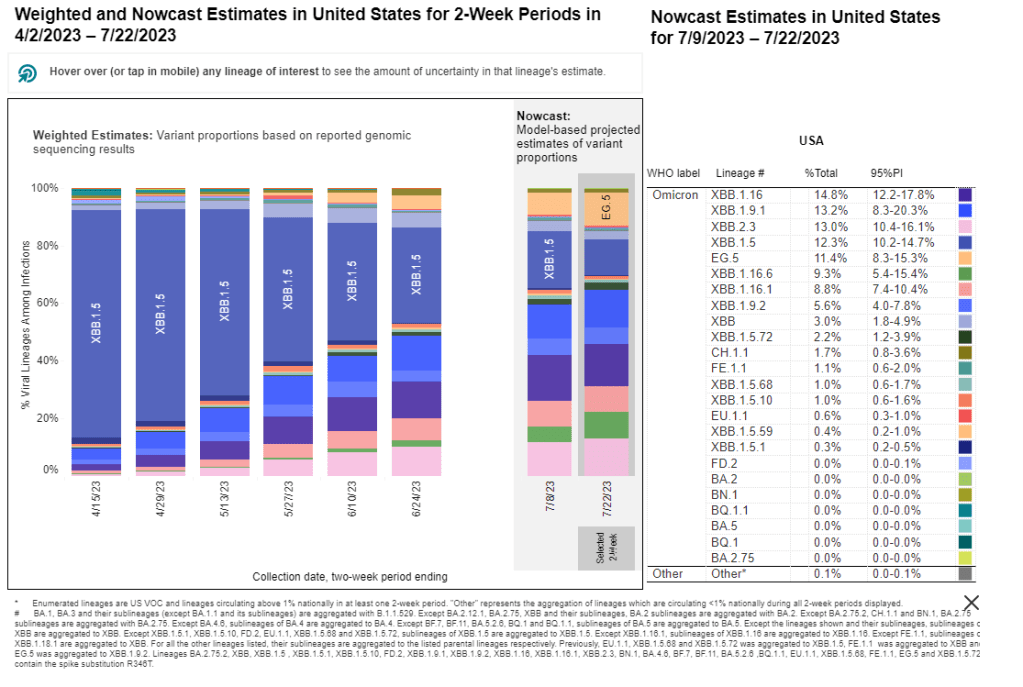

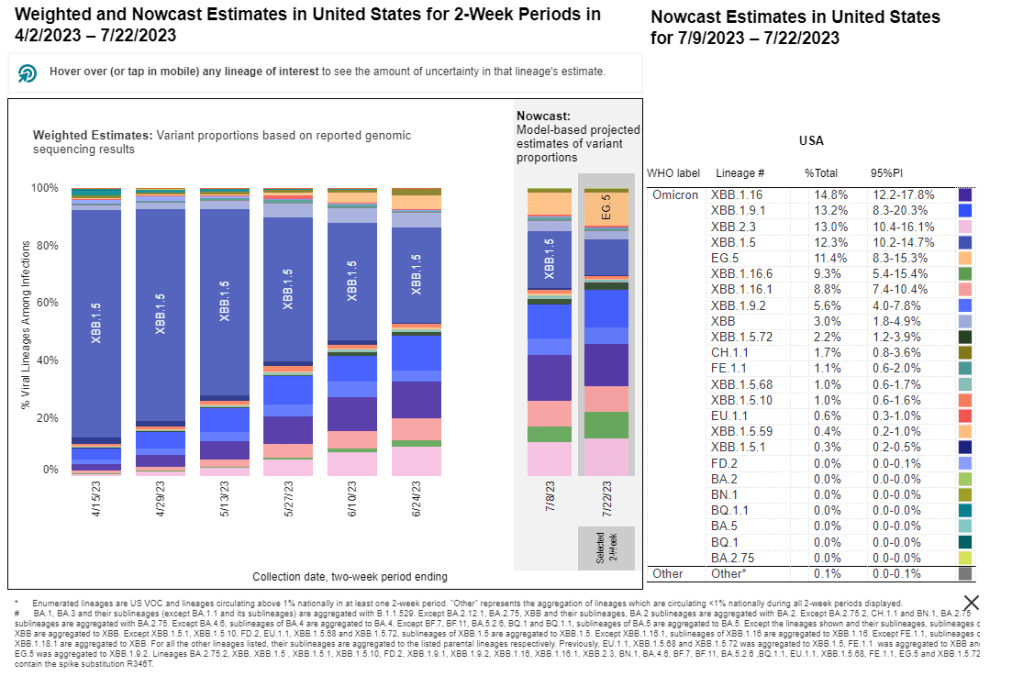

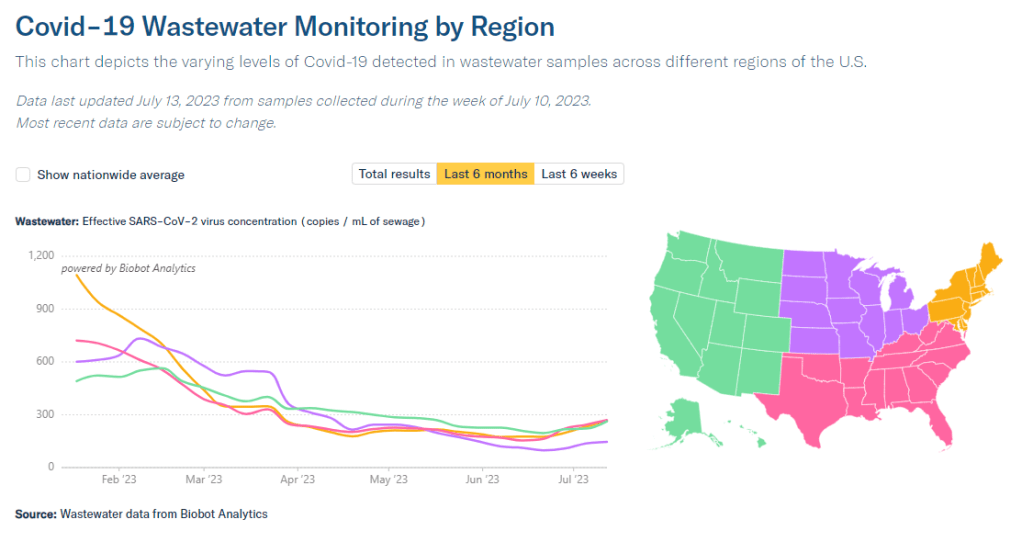

- Coordinating the executive branch’s “domestic response to public health threats that have pandemic potential or may cause significant disruption.” Current notable threats include COVID-19, mpox, polio, flu, and RSV.

- Coordinating federal science and technology efforts related to pandemic preparedness, such as developing next-generation vaccines and treatments. A current focus here is next-gen vaccines for COVID-19, though it’s unclear how this new office will coordinate with other federal agencies on that initiative, per reporting by Sarah Owermohle at STAT.

- Develop pandemic preparedness reports for Congress, including a shorter review every two years and more in-depth reports every five years.

The Biden administration has appointed retired Major General Paul Friedrich (MD), currently the senior director for global health security at the National Security Council, to lead the new office. Friedrich has decades of experience leading global health initiatives in the military and for the federal government; he advised the Pentagon in the early months of COVID-19.

Between this new office and Congress’ work on reauthorizing the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, there’s been a lot of discussion on preventing future pandemics in the last couple of weeks. This is obviously good news; COVID-19 has taught U.S. officials at all levels that they will need more resources for the next big health threat.

But at the same time, the focus on pandemic preparedness can potentially distract us from the many current health threats that we face now. That includes COVID-19 and Long COVID, along with many common diseases, chronic conditions, and other health issues that could be managed better. For example, our seasonal flu surveillance could use an upgrade!

The U.S. has plenty of resources to devote to present and future health threats; we could be doing much more on both fronts.