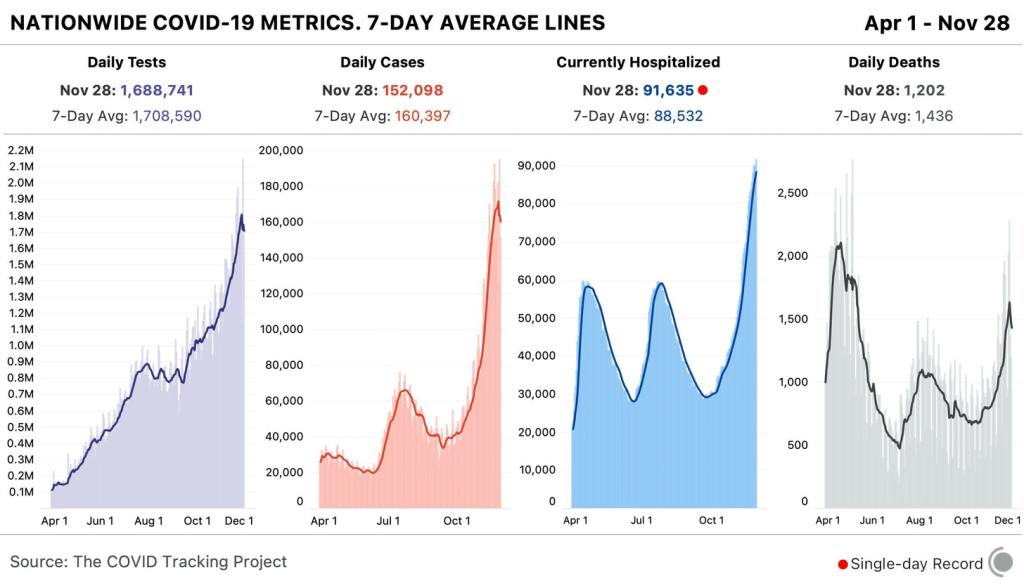

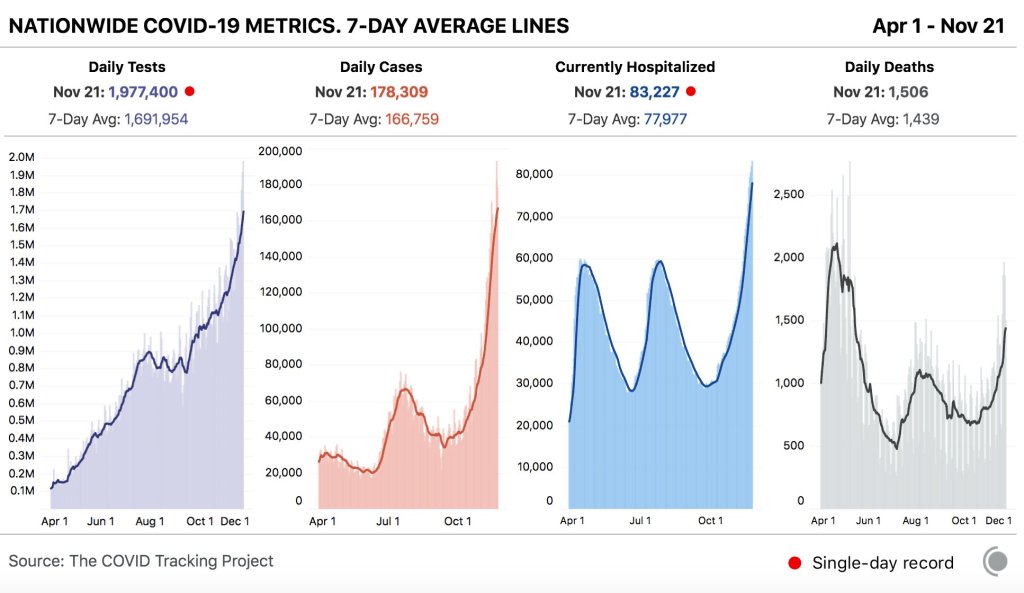

In the past week (November 22 through 28), the U.S. reported about 1.1 million new cases, according to the COVID Tracking Project. This amounts to:

- An average of 160,000 new cases each day (4% decrease from the previous week)

- 343 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 1 in 292 Americans getting diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past week

- 9% of the total cases the U.S. reported in the full course of the pandemic

1 in every 82 Americans has been diagnosed with COVID-19 since the beginning of November. Sit with that number for a minute. Picture 82 people. Imagine one of them getting sick, going to the hospital, having debilitating symptoms for months afterward. That is the weight of this pandemic on America right now.

The COVID Exit Strategy tracker now categorizes the virus spread in every state except for Maine, Vermont, and Hawaii as “uncontrolled,” and even those three states are “trending poorly.” I know we just finished an exhaustive public health news cycle about Thanksgiving travel, but… I would recommend that you start making your Christmas plans now.

America also saw:

- 10,000 new COVID-19 deaths last week (3.1 per 100,000 people)

- 91,600 people currently hospitalized with the disease, as of yesterday (93% increase from the start of November)

This week, though, I need to caveat the data pretty heavily. The public health officials who collect and report COVID-19 numbers celebrate holidays just like the rest of us; but when dashboards go dark for a day or two, those data gaps can lead to some weird trends.

Here’s how COVID Tracking Project lead Erin Kissane explains it, in a recent Project blog post:

First, by Thanksgiving Day and perhaps as early as Wednesday, all three metrics [tests, cases, and deaths] will flatten out or drop, probably for several days. This decrease will make it look like things are getting better at the national level. Then, in the week following the holiday, our test, case, and death numbers will spike, which will look like a confirmation that Thanksgiving is causing outbreaks to worsen. But neither of these expected movements in the data will necessarily mean anything about the state of the pandemic itself. Holidays, like weekends, cause testing and reporting to go down and then, a few days later, to “catch up.” So the data we see early next week will reflect not only actual increases in cases, test, and deaths, but also the potentially very large backlog from the holiday.

And indeed, new daily cases dropped from 183,000 on Wednesday to 125,000 on Thursday, rose to 194,000 on Friday, then dropped back to 152,000 on Saturday. Even in the states which still reported new cases, deaths, and tests on Thanksgiving, many testing sites and labs were closed, further contributing to reporting backlogs and discrepancies.

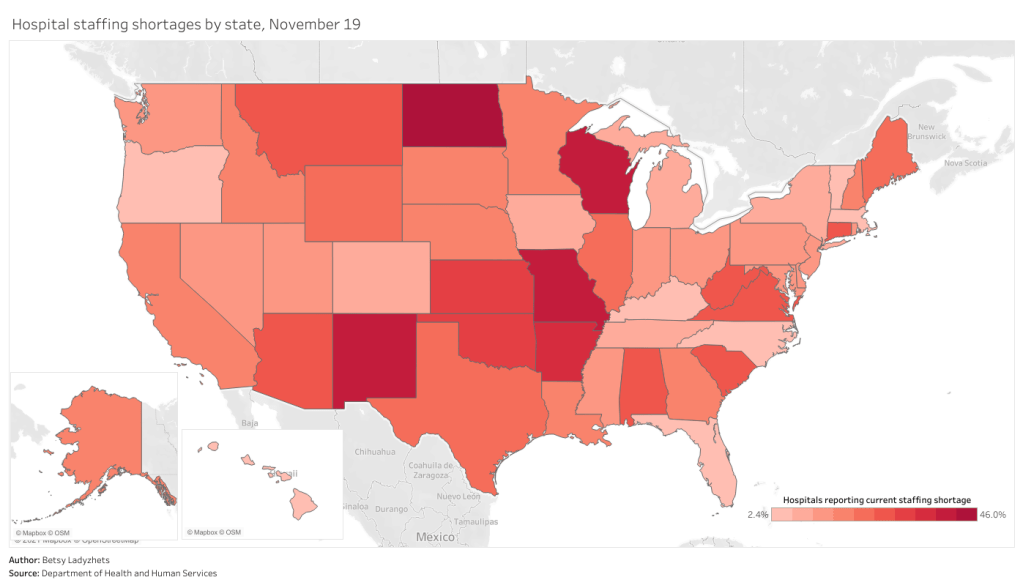

If you’re watching (or reporting) the numbers in your community, the Project recommends using seven-day averages—for example, rather than just looking at today’s new cases for evidence that the pandemic is slowing, calculate the average of today’s new cases and new cases from the six previous days. Current hospitalization figures and the hospital capacity data reported by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) may also be more reliable, as hospitals don’t take days off.

Finally, I’d like to echo the COVID Tracking Project in thanking the many thousands of people behind these data. There are healthcare workers, lab technicians, public health leaders, and data pipeline IT workers behind every single number that you see in this newsletter. I am grateful for all of their efforts.