Our second workshop happened this week!

Liz Essley Whyte, an investigative reporter at the Center for Public Integrity, discussed her work bringing White House COVID-19 reports to the public before they were officially released. Erica Hensley, an independent health and data journalist based in Jackson, Mississippi, provided advice for navigating relationships with local public health officials based on her work reporting on COVID-19 in Mississippi. And Tom Meagher, a senior editor at The Marshall Project, described the communication and coordination work behind his newsroom’s yearlong tracker of COVID-19 in the U.S. prison system. Thank you to everyone who attended!

For those who couldn’t make it live, you can watch the recording of the session below. You can also check out the slides here. I’m also sharing a brief recap of the workshop in today’s issue.

The final workshop in our series, Communicating COVID-19 data, is coming up this coming Wednesday, March 3, from 4:30 to 6 PM ET. This session will feature freelance reporter Christie Aschwanden, The Washington Post’s Júlia Ledur, and THE CITY’s Ann Choi, and Will Welch discussing strategies for both written reporting and data visualization. If you aren’t registered for the series yet, you can sign up here.

Finding and navigating government data

Liz Essley Whyte started her talk by providing backstory on the White House COVID-19 reports.

In the middle of the summer, she said, a source gave her access to documents that the White House Coronavirus Task Force was sending out to governors—but wasn’t publishing publicly. The documents included detailed data on states, counties, and metro areas, along with recommendations for governors on how to mitigate the spread. Whyte published the documents to which she’d obtained access, marking the start of a months-long campaign from her and other journalists to get the reports posted on a government portal.

“Despite weeks of me asking the White House, why aren’t these public, they were never made public for a while,” Whyte said. She continued collecting the reports and publishing them; the historical reports are all available in DocumentCloud.

If you need to find some government data—such as private White House reports—there are a few basic questions that Whyte recommended you start with:

- Who collects the data?

- Who uses it?

- Who has access to it?

- Has anyone else found it or published it before?

- What do you really want to find out? If you can’t get the data you really need, are there other datasets that could illuminate the situation?

While journalists often like to find fully original scoops, Whyte said, sometimes your best source for data could be another reporter. “There’s some really great datasets out there, especially in the health space, that people have maybe written one or two stories, but they have hundreds of stories in them.” So get creative and look for collaborators when there’s a source you really want to find.

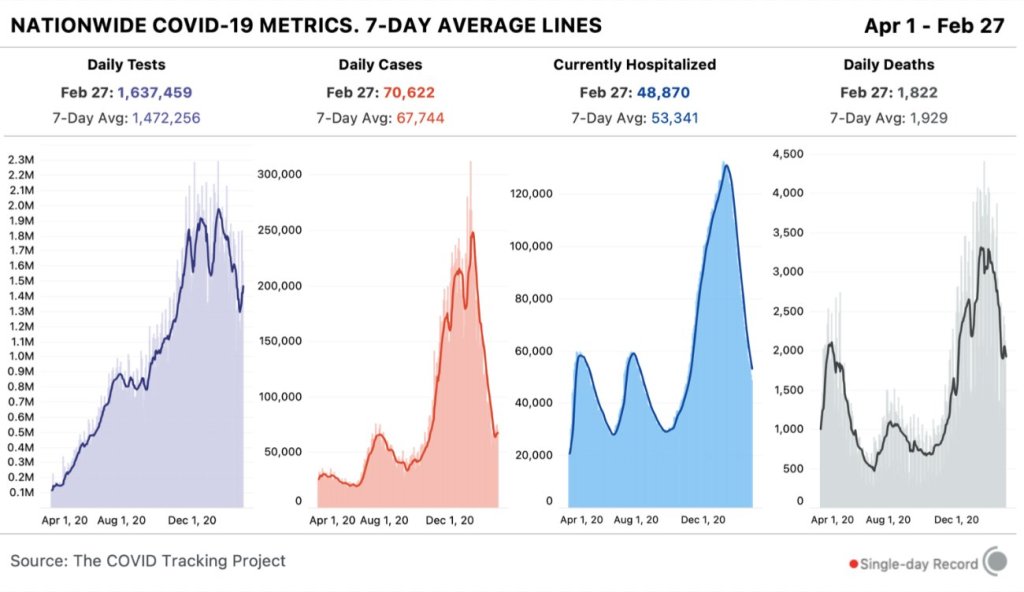

She provided a few other ideas for obtaining government data: besides getting a leak from a source (which can be hard to do), you can scour government websites, ask public information officers what data are available behind their public website, contact other officials (such as those mentioned in a one-off legislative report), or file a FOIA. Third-party sources such as the COVID Tracking Project or The Accountability Project also may have useful repositories of public information, or could help you navigate to what you need. Even for-profit data collecting companies might let journalists use their work for free.

Once you have the data, talk to your contact person for the dataset and “make sure you fully understand it,” Whyte said. Ask: Who collected the data and how? How is it being used? What’s the update schedule? How complete is it? And other similar questions, until you’re sure you know how to best use the dataset. If a data dictionary is available, make sure to comb through it and ask all your term and methodology questions.

In some cases this year, Whyte has looked at document information and contacted people who are listed as a document’s author or modifier. These are often great sources, she said, who can provide context on data even if they aren’t able to speak on the record.

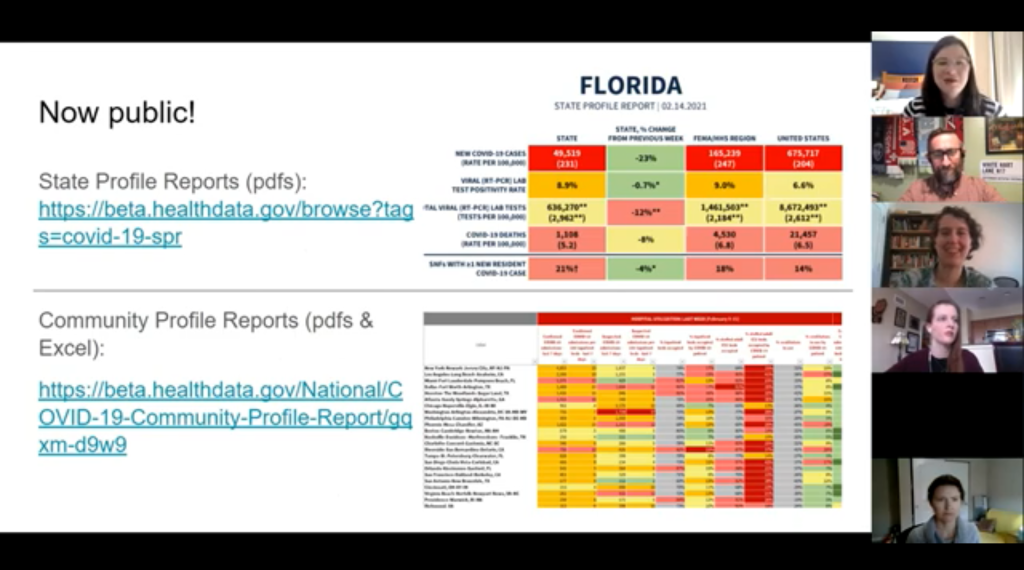

The White House COVID-19 reports that Whyte spent so much time chasing down this past summer are now public. The Trump’s administration started publishing the data behind these reports in December, and Biden’s administration has now started publishing the PDF reports themselves—albeit minus the recommendations to governors that previous iterations contained. Whyte provided a run-down of the reports on Twitter, which should be required reading for any local journalist who wants to get more in-depth with their pandemic coverage.

“I think they’re really great for local reporting because they break down all kinds of different metrics by state, county, and metro area,” she said. The reports notably make it easy for us to compare across jurisdictions, since the federal government has standardized all the data. And you can find story ideas in the data notes, such as seeing where a state or region had a data error. The CDD also wrote about these reports when they were first published.

Working with local gatekeepers to find data

Erica Hensley discussed a few lessons she learned from covering COVID-19 in Mississippi, where data availability has lagged some other states.

Local reporting, she said, provides journalists with a unique situation in which they’re directly relying on one local agency for news and data. She stressed the importance of building a relationship with agency representatives, helping them understand exactly what you’re looking for and why you need it.

“They’re [Mississippi’s public health agency] an under-resourced agency that was strapped for time to even address my request,” she said. Understanding on her part and a lot of back-and-forth helped her to eventually get those requests met.

Hensley also described how she worked to fill data gaps by doing her own analysis at Mississippi Today, a local nonprofit newsroom, then showed her work to the public health agency. For example, she used the total case numbers published by the state to calculate daily and weekly figures, and presented the data in a percent change map. This project helped Mississippi residents see where COVID-19 spread was progressing most intensely—but it also showed the state that this information was needed. She similarly calculated a test positivity rate; to this day, she said, state public health officials go to Mississippi Today’s website to see positivity rates, as these rates are not included on the state’s COVID-19 site.

When you can do some calculations yourself, Hensley said, do those—and focus your FOIA time on those data that are less readily available, such as names of schools and long-term care facilities that have faced outbreaks. Long-term care has been a big focus for her, as residents in these facilities tend to be more vulnerable.

Since Mississippi wasn’t releasing state long-term care data, she used federal data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and ProPublica to investigate the facilities. Matching up sites with high COVID-19 case counts and sites that had completed infection control training, Hensley found that the majority of long-term care facilities in the state had failed to adequately prepare for outbreaks. Her reporting revealed serious issues in the state.

Hensley advocates for local reporters to dig into long-term care stories; the CMS dataset has a lot of rich data, down to the individual facility level, that can be a springboard to stories about how facilities are (or aren’t) keeping their residents safe.

While Hensley stressed the importance of earning a local health department’s trust, she also said that health reporters need to be trusted by their colleagues. “A big part of my job early on, on top of collecting the data, was helping the newsroom understand how this applies to other local beats,” she explained. Reporters who serve as resources to each other will produce more interdisciplinary stores, and reporters who team up to request data will get the information out faster.

Building a massive system to track COVID-19 in prisons

Reporters at The Marshall Project have spent the past year tracking COVID-19 cases in U.S. prisons. Tom Meagher discussed how they did it, including a lot of external and internal communication.

After the newsroom went on lockdown, Meagher said, “Once of the first things we thought of was, prisons—being congregate living facilities—were going to be seriously affected by this pandemic.” But at first, the data they wanted simply didn’t exist.

To compile those data on COVID-19 in prisons, The Marshall Project’s team had to manage relationships with agencies in every state and D.C. They divided up all the states among their newsroom, and later worked with The Associated Press as well. At first, the reporters called every state and simply asked for numbers with no intention to publish them, in order to see if a compilation would be possible. This was easier said than done: “Prisons are not always the most transparent agencies to deal with,” Meagher said.

TMP reporters asked each agency three carefully-worded questions: How many people have been tested for the coronavirus? How many have tested positive? And how many have died? They wanted to get those numbers for both prison inmates and staff. Meagher and his colleague Katie Park had to do a lot of work to clean and standardize the numbers, which are often inconsistent across states.

The team made it clear to prison agencies that this wasn’t just a one-off ask—they came back with the same questions every week. Within a month, a lot of state agencies started setting up websites, which made data collection easier; but reporters still call and email every week in order to clarify data issues and fill in gaps. Meagher uses Google Sheets and Mail Merge to coordinate much of the data collection, cleaning, and outreach back to states with lingering questions.

The newsroom also uses a tool called Klaxon to monitor prison websites for changes and record screenshots, often useful for historical analysis. In one instance, TMP’s screenshots revealed that Texas’ justice system removed seven names from its list of prison deaths; they were able to use this evidence to advocate for names to be returned.

TMP’s data collection system is manual—or, primarily done by humans, not web scrapers. They opted for this route because prison data, like a lot of COVID-19 data, are messy and inconsistent. You might find that an agency switches its test units from people to specimens without warning, Meagher said, or fixes a historical error by removing a few cases from its total count. In these instances, a human reporter can quickly notice the problem and send a question out to the state agency.

“If we’ve learned anything from all of this, it’s that there’s a lot of different ways data can go wrong,” Meagher said. Even when public health officials are well-intentioned and questions are clearly asked, misunderstandings can still happen that lead to data errors down the line.

The goal of this dataset is really to give people insight into what’s happening—for prison inmates, for their families, and for advocates. Even agencies themselves, he said, are “eager to see how they’re doing compared to other states.” Since a similar dataset doesn’t exist on a federal level, states are using TMP’s to track their own progress, creating an incentive for them to report more accurately to begin with.

These data are freely available online, including case and death numbers for every week since March. If you have questions, Meagher and his colleagues may serve as a resource for other reporters hoping to report on COVID-19 in the prison system.

Related resources

A few links shared during this session: