Last week, I introduced you to BA.2.86, a new Omicron variant that’s garnered attention among COVID-19 experts due to its significant mutations. We’ve learned a lot about BA.2.86 since last Sunday, though there are many unanswered questions to be answered as more research is conducted.

Here’s my summary of what we know so far—and what scientists are still working to understand. Overall, this variant has some concerning properties, but more data are needed before we know what kind of impact it will have on disease transmission and severity.

Where did BA.2.86 come from?

BA.2.86 was first identified in Israel earlier this month. Scientists then picked it up in Denmark, the U.S., U.K., and several other countries across multiple continents (and in people without recent travel history), suggesting that it has been spreading under the radar for a while.

However, as I’ve noted with past variants, the country where BA.2.86 was first identified is not necessarily the country where it developed. Many countries around the world are doing fairly limited COVID-19 testing and sequencing these days, so nations like Israel and the U.S. (which have more robust surveillance, relatively speaking) are likely to catch new variants.

Why are scientists concerned about BA.2.86?

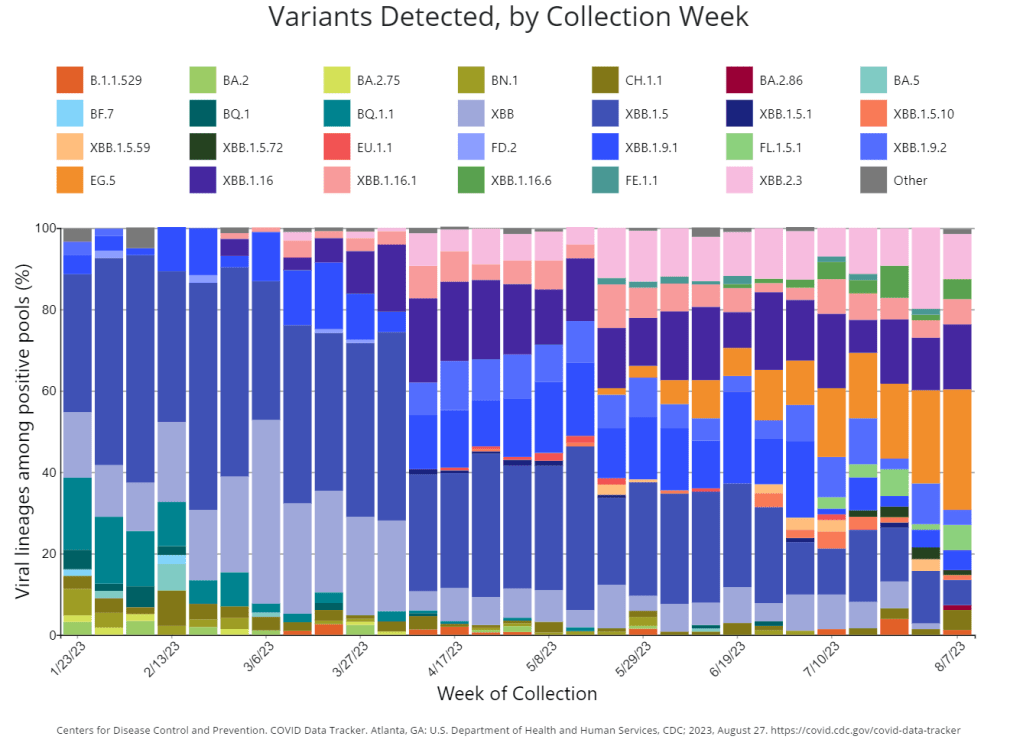

BA.2.86 worries experts because it has a number of mutations: about 30 in its spike protein, compared to BA.2, its closest relative. The spike protein is the part of the coronavirus that binds to and enters human cells, so mutations tend to accumulate here, enabling the virus to cause new infections in people who have already been infected or vaccinated.

BA.2, you might remember, was a dominant variant in early 2022, so it’s unexpected to see a descendant of this lineage pop up now. Scientists hypothesize that BA.2.86 might have evolved in a single person with a persistent infection; the virus could have multiplied and mutated over the course of several months or a year in someone originally infected with BA.2. This evolution also could have occurred in an animal population, then transferred back to humans.

Scientists have similar hypotheses about the original Omicron variant, which was also very different from circulating strains when it emerged. In fact, BA.2.86 is about as different from XBB.1.5 (a recently dominant variant globally) as Omicron BA.1 was from Delta.

Where has BA.2.86 been identified so far?

Surveillance efforts in many countries have now found BA.2.86, ranging from Thailand to South Africa. This variant is evidently already spreading globally; unlike Omicron’s initial emergence, however, we don’t have a singular country to watch for signals of how BA.2.86 may impact transmission trends.

In the U.S., researchers have found BA.2.86 in three different states:

- One case in Michigan, from a person tested in early August

- One traveler returning to a D.C.-area airport from Japan, their infection caught through the CDC’s travel surveillance program

- Wastewater from a sewershed in Elyria, Ohio

As surveillance is currently fairly uneven across the U.S., we can likely assume that BA.2.86 is present in other states already. Continued testing in the next few weeks will provide a clearer picture of the situation.

How does BA.2.86 impact transmission and disease severity?

This is one question that we can’t answer yet, though scientists are concerned about its potential. In a risk assessment report published this past Wednesday, the CDC said that mutations present in BA.2.86 suggest that this variant may have greater capacity to “escape from existing immunity from vaccines and previous infections” when compared to recent variants.

However, this is just a hypothesis based on genomic sequences. The CDC report cautions that it’s too soon to know how transmissible BA.2.86 is or any impact it may have on symptom severity. To answer this question, scientists will need to identify more cases caused by this variant, then track their severity and spread.

Will our new booster shots work against BA.2.86?

The FDA and CDC are planning to distribute booster shots this fall, based on the XBB.1.5 variant that dominated COVID-19 spread in the U.S. this spring and earlier in the summer. As Eric Topol points out in a recent Substack post, this booster choice made sense a couple of months ago, but it’s unlikely to work well against BA.2.86 if that variant takes off.

More research is needed on this topic, of course, but the existing genomic data is concerning. Having an XBB.1.5 booster this fall, if we see a BA.2.86-driven surge, would be like having a booster based on Delta, when Omicron is spreading: better than no booster, but unlikely to provide full protection.

“The strategy of picking a spike variant for the mRNA booster at one point in time and making that at scale, going through regulatory approval, and then for it to be given 3 or more months later is far from optimal,” Topol writes. “We desperately need to pursue a variant-proof vaccine and there are over 50 candidate templates from broad neutralizing antibodies that academic labs have published over the last couple of years.”

Will current COVID-19 tests and treatments work for BA.2.86?

According to the CDC’s risk assessment, current tests should still detect BA.2.86 and treatments should work against it, based on early studies of the variant’s genomic sequences. More research (from health agencies and companies) will provide further data on any changes to test or treatment effectiveness.

Mara Aspinall points out in her testing-focused Substack that rapid tests, in particular, tend to be unaffected by variants because they test for the N protein, a different part of the coronavirus from the spike protein (which is the main area of viral evolution). However, if you’re taking a rapid test, it’s always a good idea to follow best practices for higher accuracy—testing multiple times, swabbing your throat, etc.—and get a PCR if available.

How are scientists tracking the coronavirus’ continued evolution?

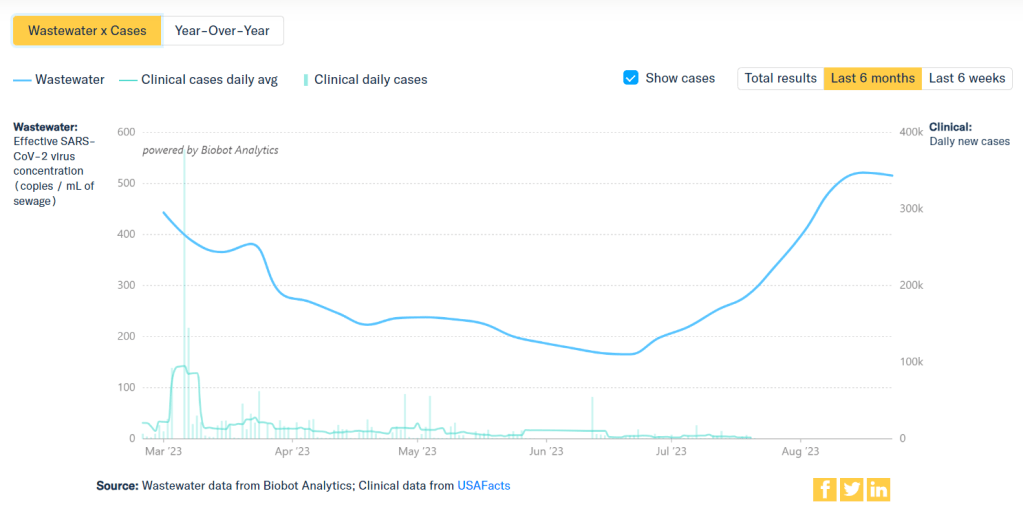

BA.2.86 has arrived in an era of far less COVID-19 surveillance, compared to what we had available a year or two ago. Most people rely on rapid tests (if they test at all), which are rarely reported to the public health system and can’t be used for genomic surveillance. As a result, it might take longer to identify BA.2.86 cases even as this variant spreads more widely.

However, there are still some surveillance systems tracking the virus—and all are now attuned to BA.2.86. A couple worth highlighting in the U.S.:

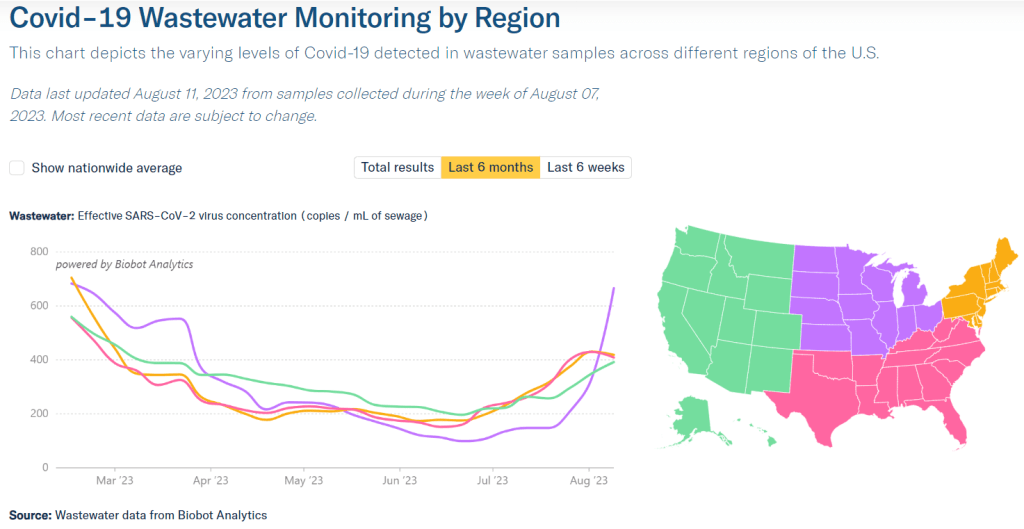

- Wastewater surveillance increasingly includes testing for variants. The CDC has a dashboard showing variant testing results from sewage; this is happening in about 400 sewersheds now and will likely increase in the future.

- The CDC also supports a travel surveillance program at major international airports, in partnership with Concentric by Ginkgo and XpressCheck. This program caught one of the first BA.2.86 cases in the U.S. (the traveler from Japan mentioned above).

- Several major testing companies and projects continue virus surveillance, via both limited PCR samples and wastewater. These include Helix, Biobot, and WastewaterSCAN.

What will BA.2.86 mean for COVID-19 spread this fall and winter?

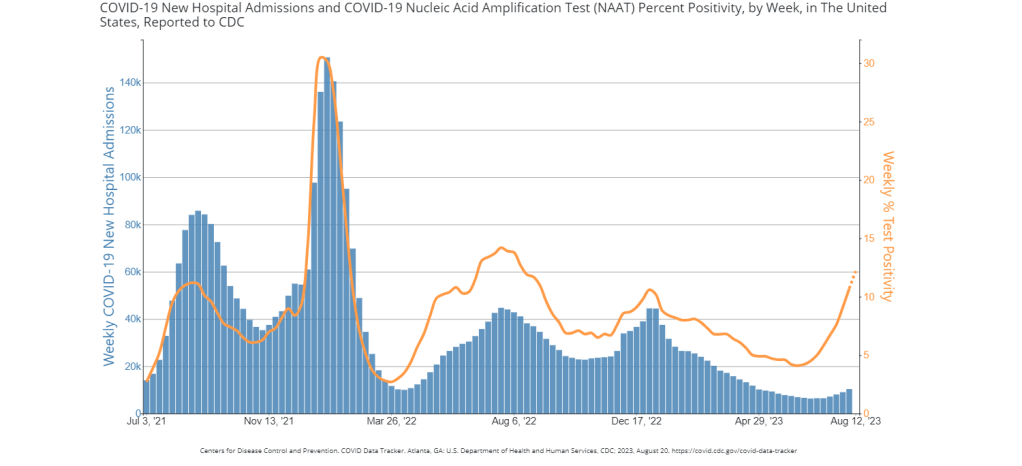

While BA.2.86 is similar to Omicron BA.1 in its level of mutations, it’s not yet driving significant disease spread at the same level that we saw from Omicron when that variant first emerged in late 2021. All warnings at this point are tentative, based on very limited data.

In a Twitter thread last week, virologist Marc Johnson pointed to three potential scenarios for BA.2.86:

- It could “fizzle,” or fail to outcompete currently-circulating variants and spread widely despite its concerning array of mutations.

- It could “displace” the current variants and contribute to increased transmission, but not cause a huge wave on the same level as Omicron BA.1 in late 2021.

- It could cause a major wave, comparable to the initial Omicron spread.

Based on analysis from Johnson and other experts I follow, the second scenario seems most likely. But if the U.S. and other countries had meaningful public health protections in place, we could actually contribute to those odds, rather than leaving things up to evolutionary chance. Remember: variants don’t just evolve in a vacuum. We create them, by letting the virus spread.

Sources and further reading:

- CDC Risk Assessment Summary for SARS CoV-2 Sublineage BA.2.86

- U.K. Health Security Agency Risk assessment for SARS-CoV-2 variant V-23AUG-01 (or BA.2.86)

- A Quick Update on the BA.2.86 Variant, from Eric Topol (Ground Truths)

- A new variant: BA.2.86, from Katelyn Jetelina (Your Local Epidemiologist)

- New COVID variant BA.2.86 spreading in the U.S. in August 2023. Here are key facts experts want you to know. (CBS News)

- CDC says it’s too soon to assess risk posed by new Covid subvariant (STAT News)