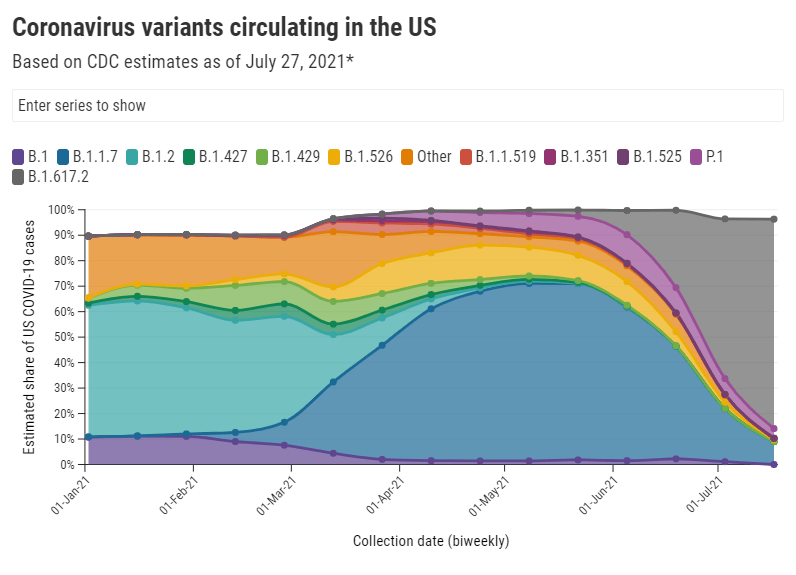

It should be no surprise, at this point in the summer, that Delta (B.1.617.2) is bad news. From the moment it was identified in India, this variant has been linked to rapid transmission and rapid case increases, even in areas where the vaccination rates are high.

This week, however, the CDC’s changed mask guidance—combined with new reports on breakthrough cases associated with Delta—has triggered widespread conversation about precisely how much damage this variant can do. “I’ve not seen this level of anxiety from everyone since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Katelyn Jetelina wrote in her newsletter Friday.

In the CDD today, I’m unpacking six key statements that you’ve likely seen in recent headlines, including where the statistics came from and what they mean for you.

1. Delta causes a viral load 1,000 times higher than the original coronavirus strain.

This number comes from a recent study in Guangzhou, China that was published as a preprint earlier in July. The researchers looked at viral load, a measurement of how much virus DNA is present in patients’ test samples; a higher viral load generally means the patient can infect more people, though it’s not a one-to-one relationship (more on that below).

Based on measurements from 62 people infected with Delta, the researchers concluded that Delta patients have about 1,000 times more virus in their bodies compared to patients infected with the original coronavirus strain in early 2020. This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed, but outside experts have cited it as evidence behind Delta’s super-spreading ability.

For more explanation on how Delta differs from past coronavirus strains, check out this KHN story by Liz Szabo.

2. Delta causes similar viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people who get infected.

This finding comes from a highly anticipated CDC report published Friday in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). CDC researchers measured viral loads—remember, a reflection of how much virus DNA is in a patient’s body—in vaccinated and unvaccinated people who got infected during an outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts. They found that the two groups had similar measurements, on average. Test samples in this outbreak were also sequenced; 90% of cases in the outbreak were definitively caused by Delta.

It’s important to be precise when we talk about this CDC report, because viral load is just one specific measurement. While the viral load can reflect how capable someone is of transmitting the coronavirus, the CDC’s data do not definitively tell us that vaccinated and unvaccinated people are equally capable of transmitting Delta.

Experts commenting on the CDC’s findings have said that other factors, such as length of infection and virus presence in a patient’s nose and mouth, also play into coronavirus transmission.For example, here’s a quote from a Science News story discussing the CDC’s findings:

The result “just gives you an indication of how much viral RNA is in the sample, it tells you nothing about infectiousness,” says Susan Butler-Wu, a clinical microbiologist at the University of Southern California. These data “are a cause for concern, but this is not a definitive answer on transmissibility” from vaccinated people, she says.

And here’s a Twitter thread from a vaccine scientist discussing how the CDC has conflated viral load measurements with actual transmission:

In other words: vaccinated people are not capable of spreading Delta to the same degree as the unvaccinated. The infection and transmission risks for vaccinated people are still much lower. Here’s one reason why…

3. A breakthrough infection will be over faster than a non-breakthrough infection.

This finding comes from a study out of Singapore, published yesterday as a preprint. Researchers looked at viral loads over time for patients infected with Delta, comparing numbers for those patients who had and had not been vaccinated. They found that the viral load decreased more quickly in those vaccinated patients who had a breakthrough case, signifying that vaccinated patients both recover more quickly and lose their ability to get someone else infected more quickly.

In other words, when a vaccinated person has a breakthrough case, their immune system is more prepared to face the coronavirus. That prepped immune system will help the person avoid severe disease, while also getting the virus out of the body more quickly than the immune system would be able to without a vaccine’s help.

This study is not yet peer-reviewed, but it aligns with other research showing that vaccinated people with breakthrough cases tend to have mild symptoms and spend less time being contagious.

4. An interaction of one second is enough time for Delta to spread from one person to another.

In spring 2020, public health leaders agreed on a rule of thumb for COVID-19 risk: if you were indoors with someone, unmasked, for at least 15 minutes, that person qualified as a “close contact” who could give you the coronavirus, or vice versa. Now, with Delta, the equivalent of that 15-minute close contact is one second. I first saw this statistic in a STAT News interview with epidemiologist Dr. Céline Gounder, but it’s been reported in other publications as well.

Let me emphasize here, though, that this one-second rule applies to indoor transmission. We don’t yet know how much Delta increases the risk of outdoor transmission, which was almost entirely negligible for past variants.

5. The average person with Delta infects at least twice as many others as the average person with the original coronavirus strain.

In spring 2020, the average person who got sick with COVID-19 would infect a couple of others, while a select few would cause superspreading events. Now, we’re learning that the average person who gets Delta can infect more. An internal CDC report leaked by the Washington Post says that Delta may infect eight or nine people on average and spreads “as easily as chickenpox.”

While this comparison is obviously pretty concerning, outside experts have been skeptical of the CDC’s generalization of data from that one Massachusetts outbreak. Plus, the CDC’s estimate of Delta’s capacity for infection is higher than estimates we’ve seen from other sources. Studies out of England suggest that the variant infects five to seven people on average—still high, but not quite chickenpox levels.

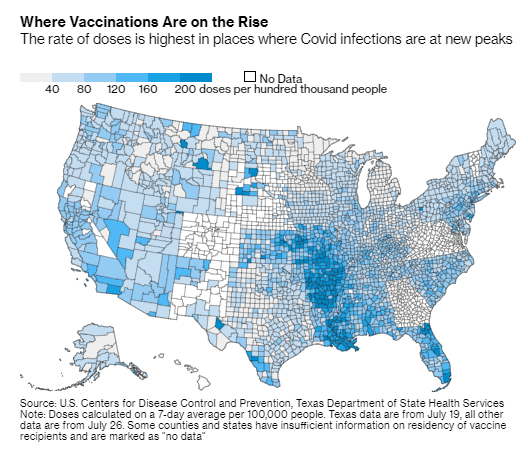

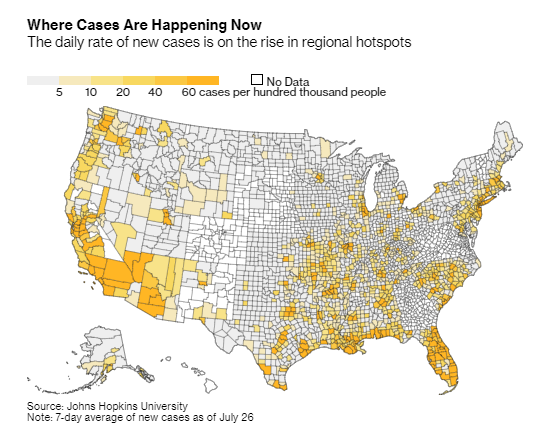

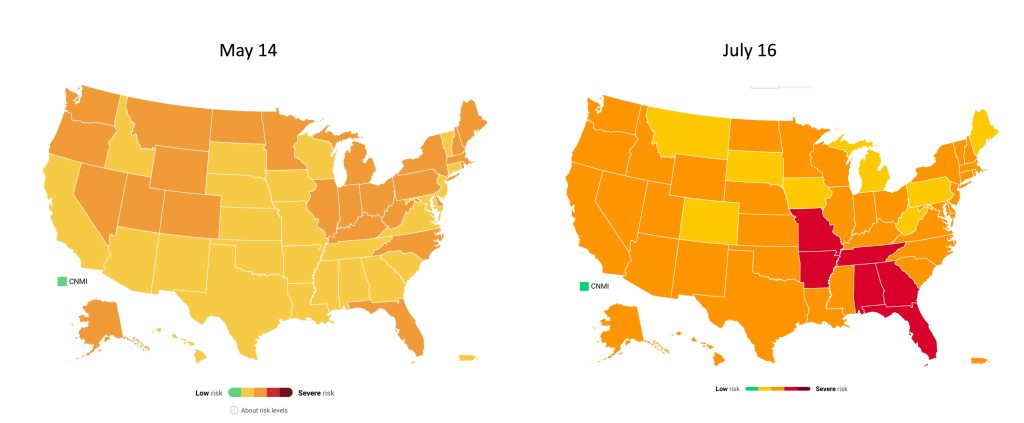

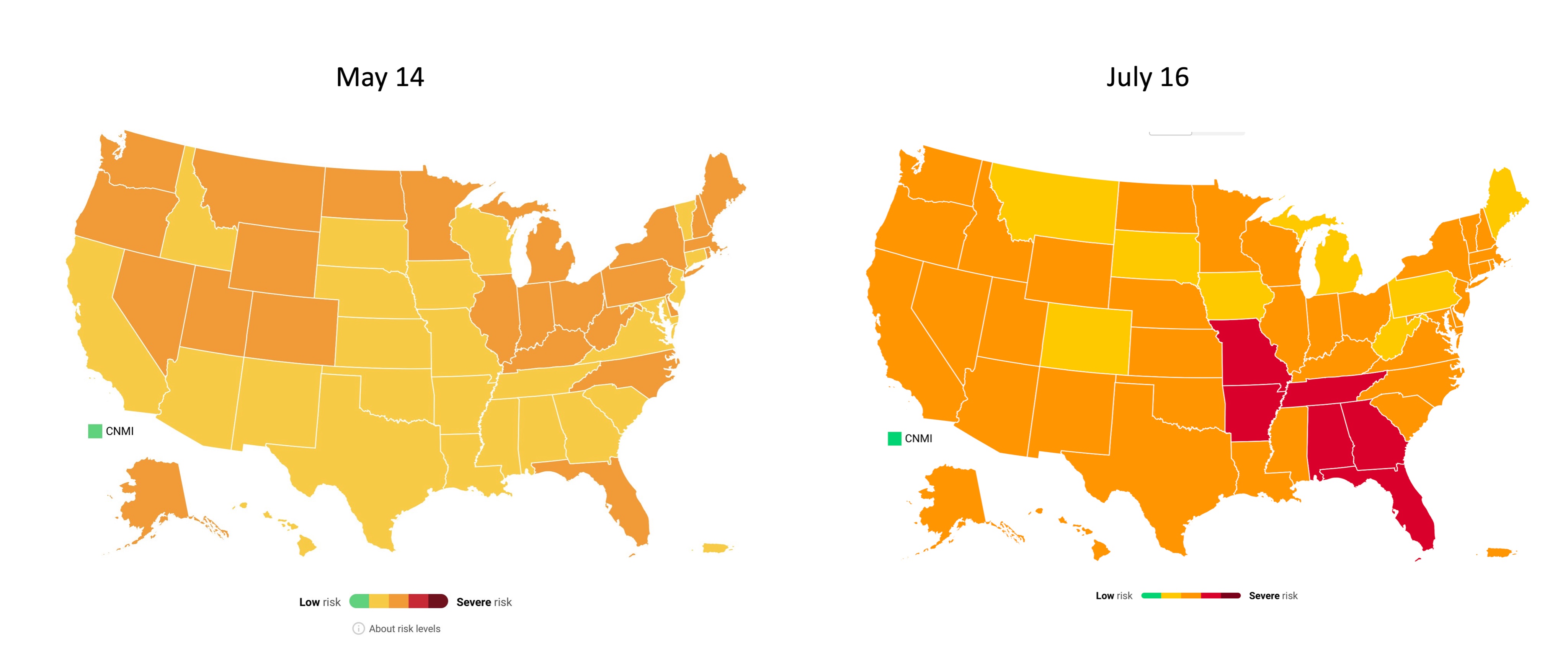

6. Hospitalizations are rising in undervaccinated areas, while well-vaccinated areas are on the alert.

Florida has been setting COVID-19 records recently. The state now has more people in the hospital with COVID-19 than at any other time during the pandemic, including the winter surge.

Meanwhile, hospitalizations in Texas are up more than 300% from lows in late June. Austin is running out of ICU beds. Louisiana, Arkansas, and Nevada have all seen more than 10 new COVID-19 patients for every 100,000 residents in the past week. And the healthcare workers treating these patients are burnt out from over a year of pandemic work.

In well-vaccinated areas, hospitalizations are low for now; even with Delta, the vaccines do a great job of protecting people against severe disease and death. But hospitals in these cities are still on high alert, ready to treat unvaccinated patients and those seniors, immunocompromised patients, and others for whom the vaccines may not be as effective.

For example, see this thread from University of California San Francisco medical professor Bob Wachter. (San Francisco has the highest vaccination rate of any city in America.)

TL;DR

The TL;DR here is: Delta is way more contagious than any variant we’ve seen before. For unvaccinated people, any indoor, unmasked interaction with someone who has Delta—even a very short interaction—is enough for you to get infected. For vaccinated people, the risk of getting and spreading Delta is elevated compared to past coronavirus strains, but it is still far lower than the risk for unvaccinated people.

So, when the CDC suggests that vaccinated people go back to mask-wearing (if you ever stopped), the agency is saying, wear a mask on behalf of the unvaccinated people around you. Those who are vaccinated are at more risk now than they were in May or June, but vaccination is still the best protection we have against infection, transmission, and—most importantly—severe COVID-19 disease.

Or, to quote WNYC health and science editor Nsikan Akpan: “The vaccines will keep you from dying. Masks will keep away infections. Otherwise, the COVID odds are against you.”