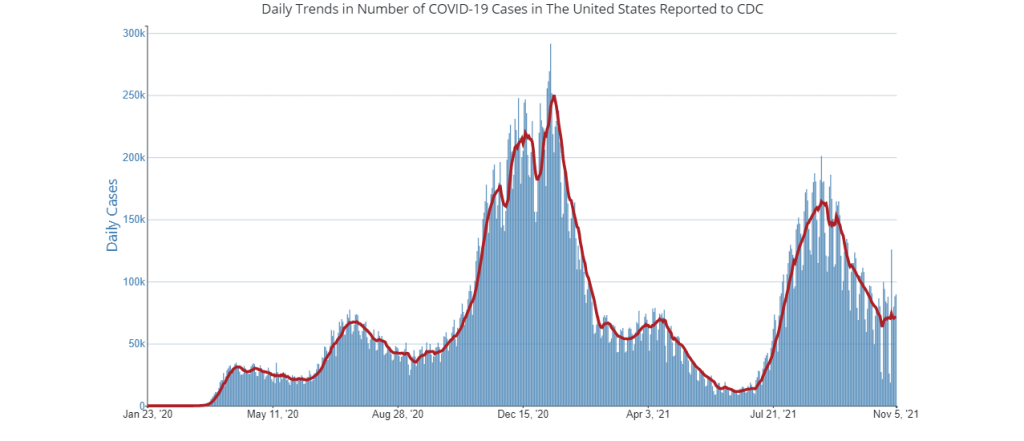

In the past week (November 6 through 12), the U.S. reported about 510,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 73,000 new cases each day

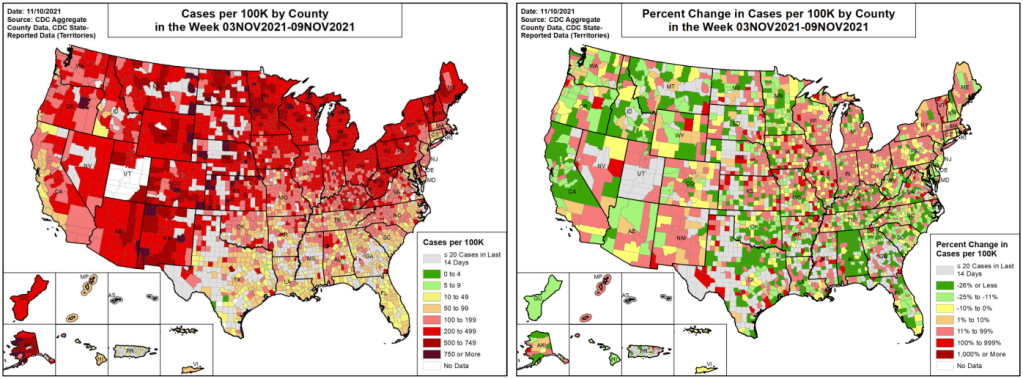

- 156 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 3% more new cases than last week (October 30-November 5)

Last week, America also saw:

- 36,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (11 for every 100,000 people)

- 7,000 new COVID-19 deaths (2.1 for every 100,000 people)

- 100% of new cases are Delta-caused (as of November 6)

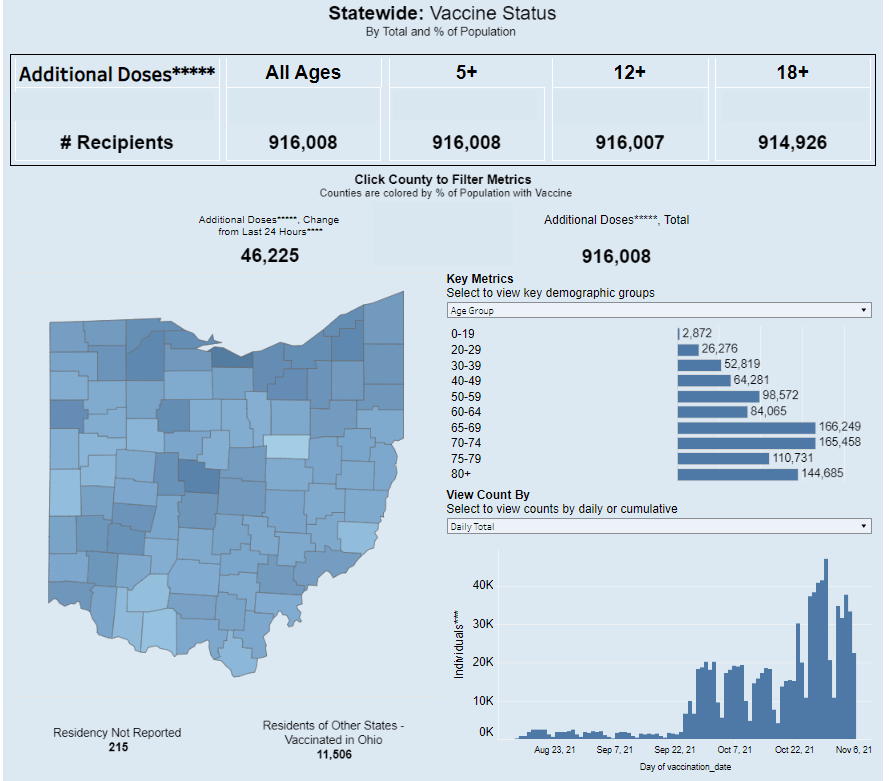

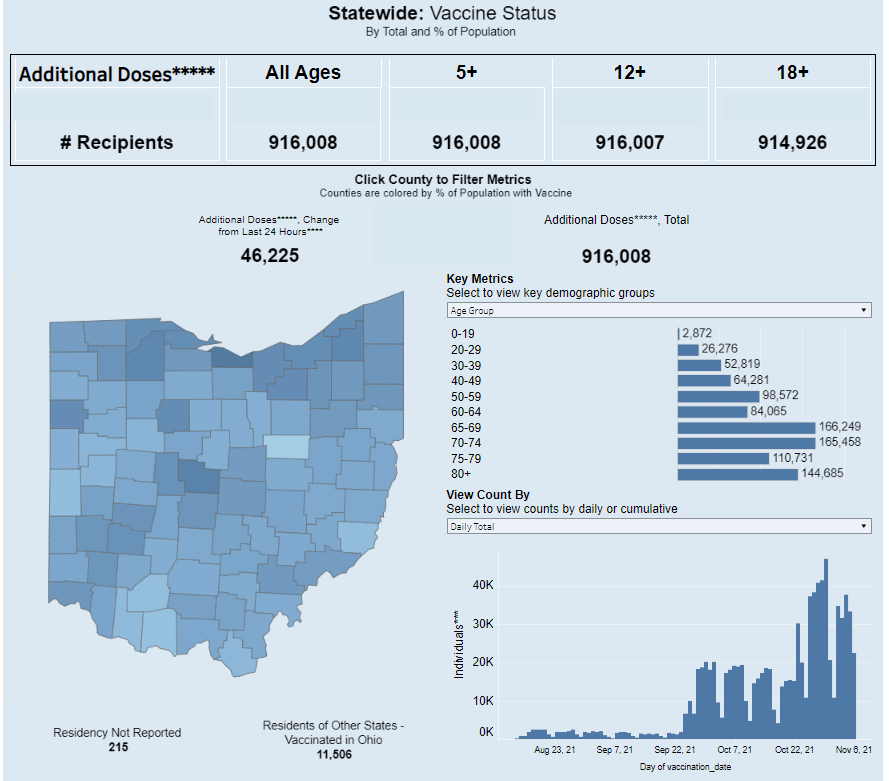

- An average of 1.4 million vaccinations per day (including booster shots; per Bloomberg)

It may be happening slowly, but the U.S. is clearly at the start of a winter COVID-19 surge. The number of newly reported cases rose this week for the first time since early September, while the number of COVID-19 patients in hospitals has plateaued.

Delta is still causing practically 100% of COVID-19 cases in the country, so a new variant is probably not to blame for this potential surge. Instead, it’s a consequence of the cold weather, combined with less-stringent safety behaviors among many Americans as we approach the holiday season. One epidemiologist told NBC that a surge may be “inevitable” at this time of year.

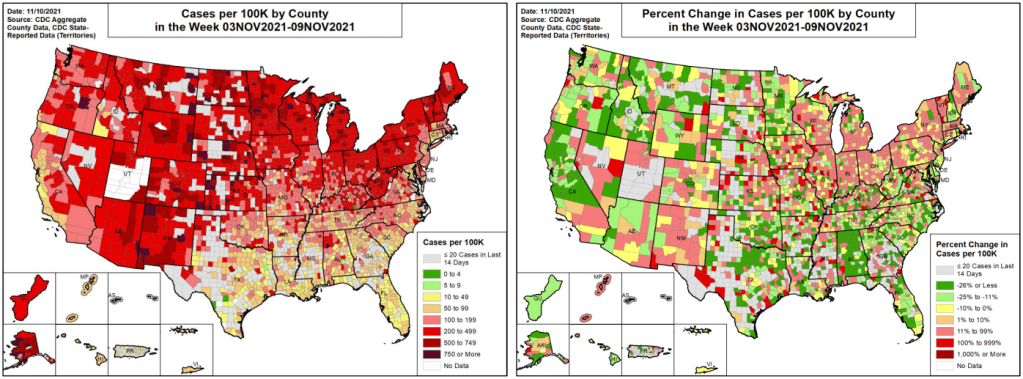

In line with COVID-19’s cold-weather advantage, many Northern states are seeing cases increase right now as Southern states—which were hit harder by the summer Delta surge—have lower transmission levels. Alaska, North Dakota, New Mexico, Montana, and Wyoming had the highest case rates last week, per the latest Community Profile Report.

Cases are also rapidly increasing in Maine, Vermont, Minnesota, Michigan, Colorado, and other chillier states. At Vermont’s St. Michael’s College, Halloween parties were a major source of new COVID-19 cases—even though 98% of people on campus are vaccinated, according to local outlet WCAX3.

Still, it’s important to point out here that the U.S. is in a far better spot now than we were at this time last year. As Dr. Ashish Jha pointed out on Twitter recently, we have winter coming and the vast majority of schools in the country are open, but cases are flat rather than rising sharply as they did last November.

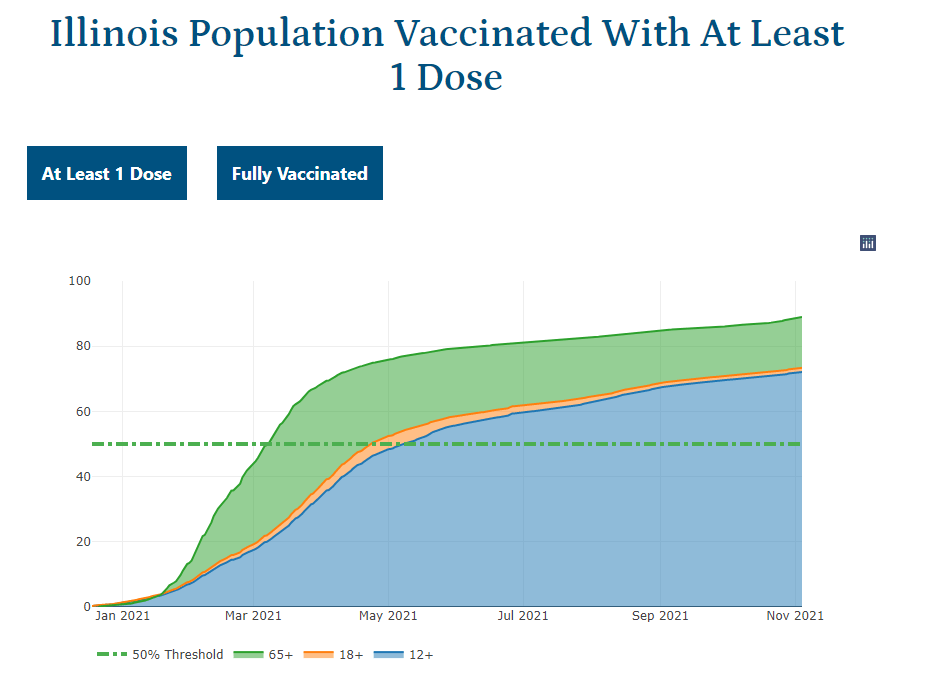

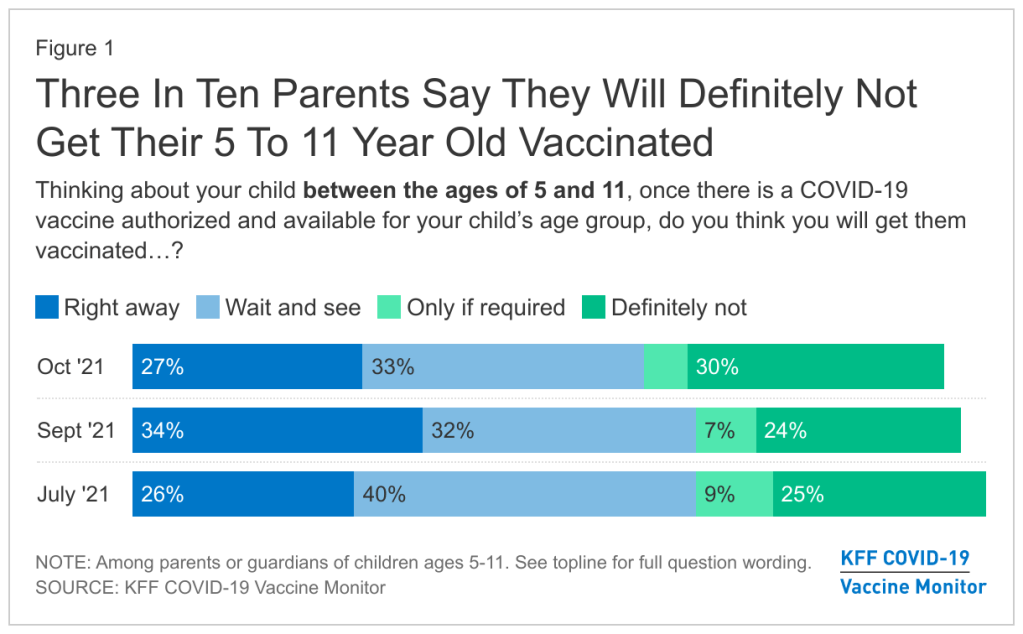

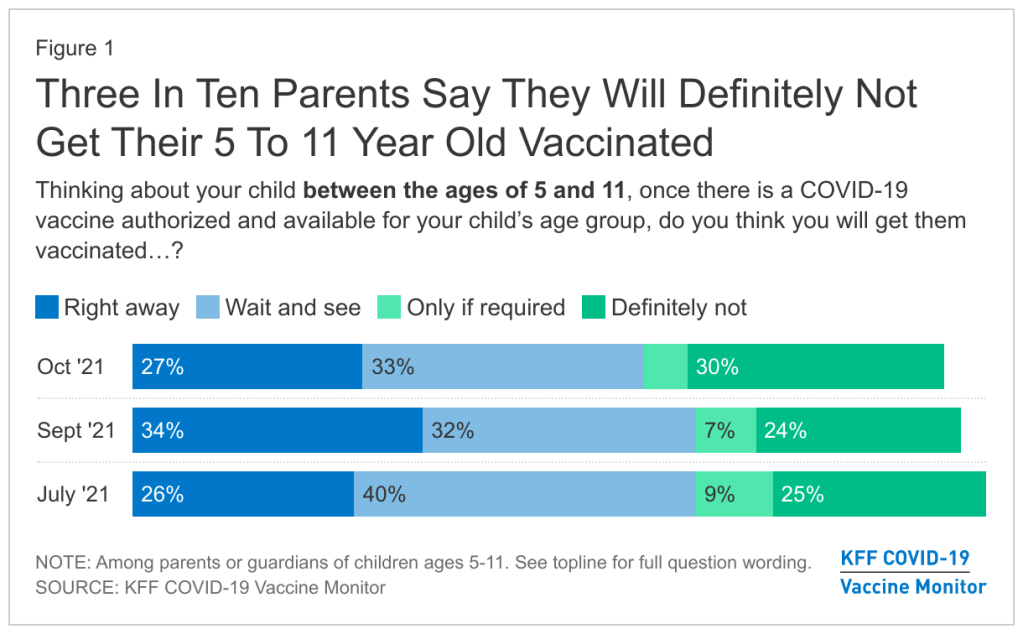

Of course, we have vaccines to thank for this improved position. More than two-thirds of the U.S. population has received at least one vaccine dose; as of this week, that number includes over one million children under age 12, according to the CDC. Vaccinating more children and other people who are currently unvaccinated, booster shots for seniors, and continued use of masks and testing can help keep case numbers (relatively) low as we head into the coldest months.