My second big story this week is a detailed report about New York City’s wastewater surveillance program, highlighting its lack of transparency. You can read the story on Gothamist and/or on MuckRock. I’m particularly excited to share this one with NYC-based readers, as it uncovers a public program that’s been running under our feet for nearly three years.

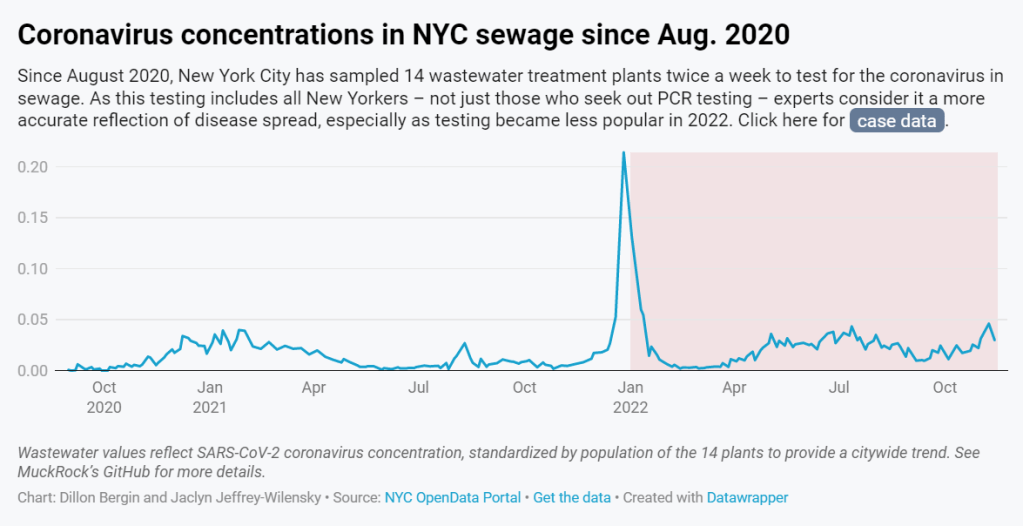

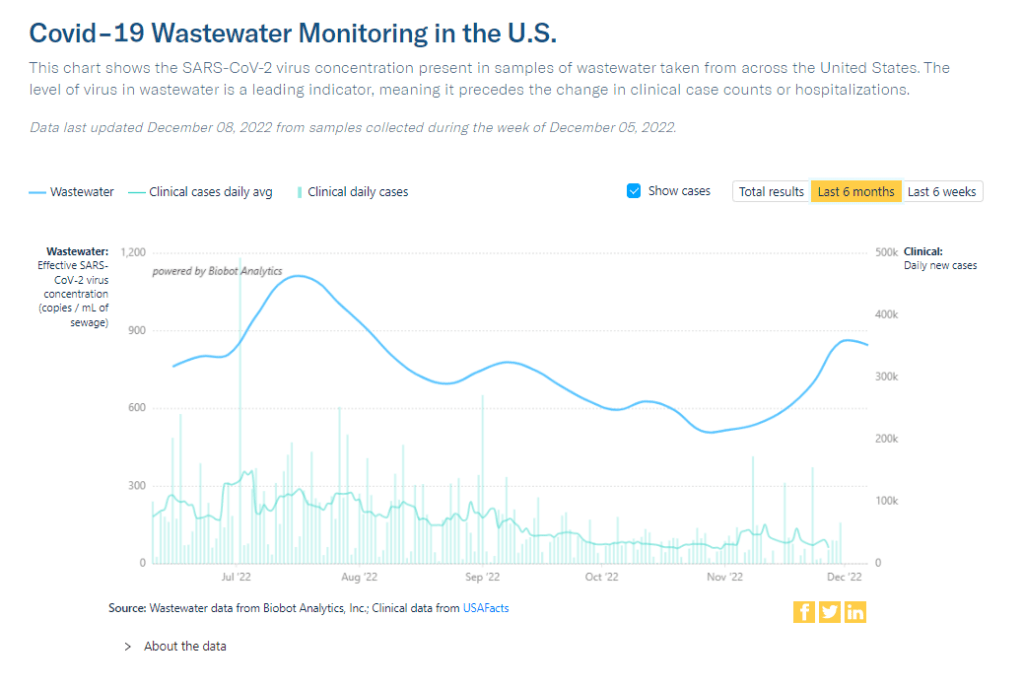

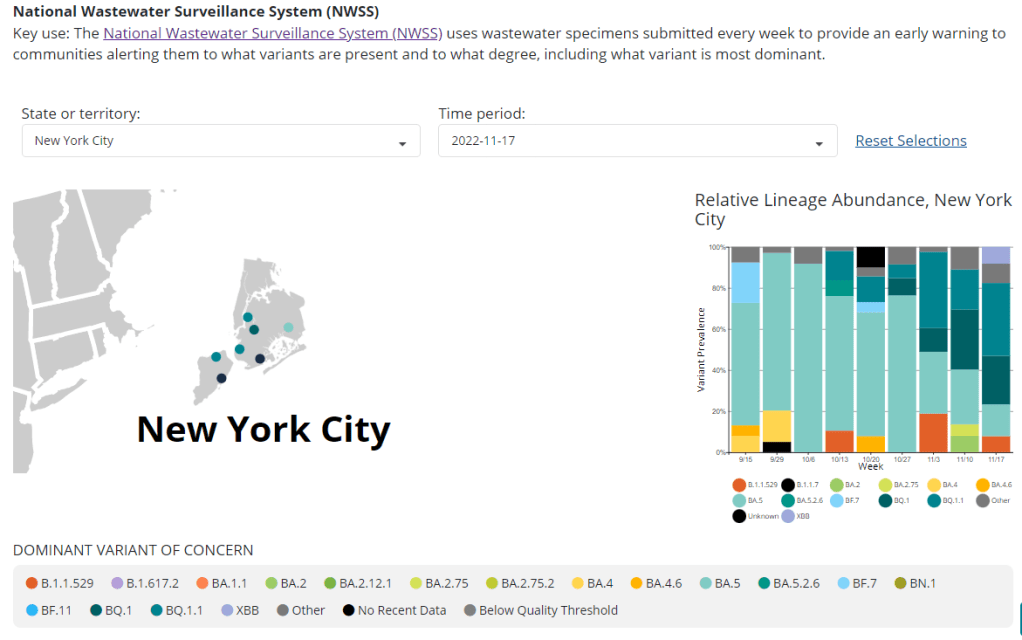

Longtime readers might remember that, back in April, I noticed that NYC wastewater data had disappeared from the CDC’s national dashboard. And the city’s data stayed unavailable even when other locations (which were similarly interrupted by the CDC’s switch between wastewater contractors) resumed reporting to the dashboard.

That observation piqued my curiosity about how, exactly, NYC agencies are testing our wastewater—and what they’re doing with the data. So, I started investigating, with the support of MuckRock and Gothamist/WNYC. My project eventually revealed the answers to my questions: while NYC has set up an impressive, novel program to test all 14 city wastewater treatment plants for COVID-19, the health department doesn’t appear to be taking advantage of these results.

In a joint statement, NYC’s health and environmental protection agencies said that they still see wastewater surveillance as a “developing field” and are skeptical about its utility for public health. Even though NYC’s program has been running since early 2020 and cost over $1 million. And even though other wastewater programs across the U.S. and internationally have demonstrated the potential of this type of data.

Here are the story’s main findings, as drafted for MuckRock’s version of the article:

- New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection created a brand-new program to test city wastewater for COVID-19 in 2020, working with limited lab equipment and personnel to sample from 14 sewage treatment plants across the city. In doing so, the city brushed off assistance offered from “multitudes of academics” and private sector researchers, and set up its program in-house. It has cost more than $1 million over the past three years.

- But the city didn’t publicly post any wastewater data until January 2022, almost two years after testing started. Unlike other large cities, such as Boston, New York City lacks a public dashboard for wastewater data. The city’s data available on dashboards run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York State are often delayed by a week or more, making it less useful for New Yorkers seeking advanced warning about potential new surges.

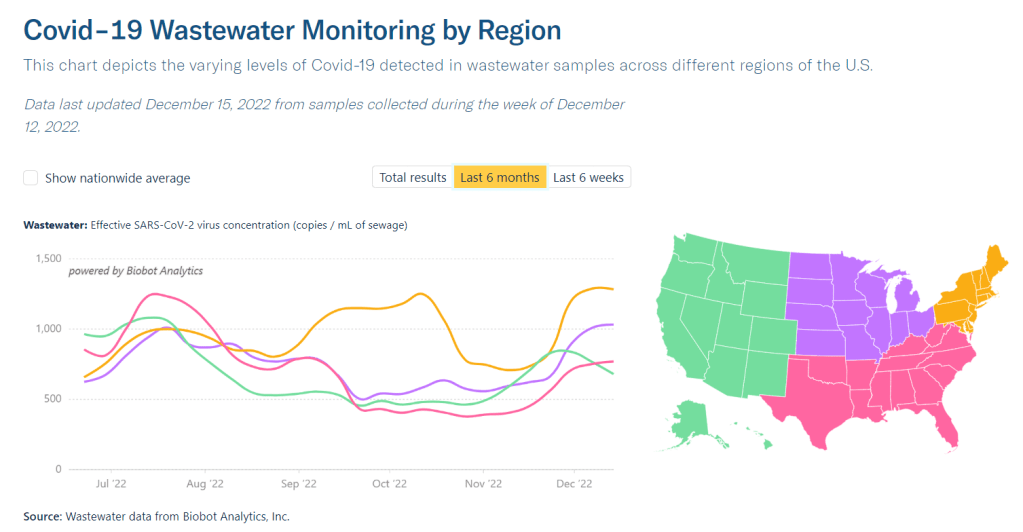

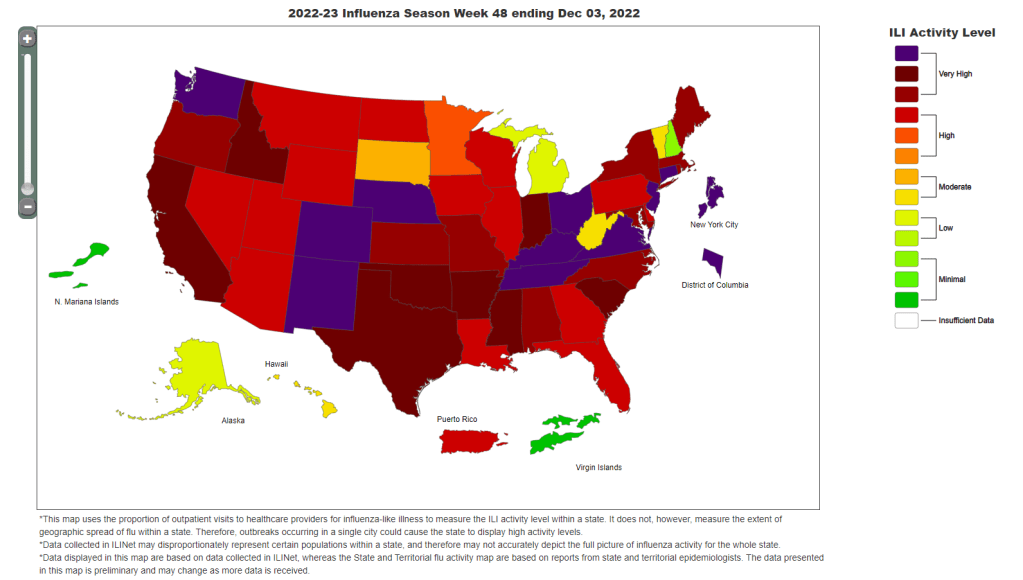

- In other parts of the U.S. — and at Columbia University in uptown Manhattan — wastewater surveillance is used for public health strategies, such as encouraging people to get PCR tests or sending extra resources to hospitals before a surge. However, New York City’s health and environmental agencies say they still consider wastewater research a “developing field” and aren’t using it for policy decisions.

- In response to our questions, city health and environment agency officials argued that wastewater results “do not generally provide a complete picture” of how COVID-19 is spreading and said, unlike in other parts of the country, trends in city wastewater data tend to align with case counts rather than predicting them. But wastewater has shown a higher level of COVID-19 spread than PCR testing, as the latter became less available in 2022, according to Gothamist and MuckRock analyses. This pattern suggests that the sewage numbers may more accurately reflect actual disease patterns.

- A bill introduced to the New York City Council in August would make the wastewater surveillance program permanent, expand it to other public health threats as needed, and require the health department to report data on a public dashboard.

For readers outside NYC, I think this story provides an informative case study of the hurdles that wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 (and other diseases) will need to clear.

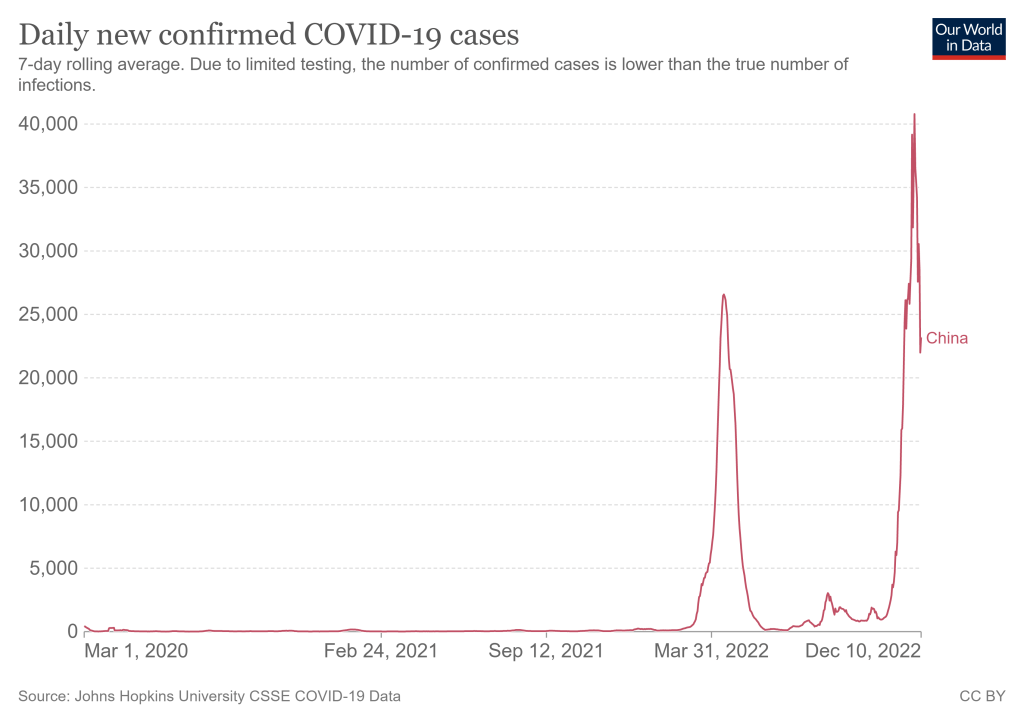

First, you have the resource challenges. If the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, which oversees the largest municipal water network in the country, had a hard time getting equipment and personnel for testing—imagine the challenges facing small, rural public health departments.

Next, after testing is set up, you have to interpret the data. NYC’s health department seems to be somewhat stuck on this step, with no public dashboard and its insistence that city residents should look at clinical case data—which we know are a significant undercount of true infections—rather than wastewater data. To be fair, wastewater data are new terrain for public health experts, with a lot of analytical issues. (See my MuckRock/FiveThirtyEight story from the spring for more details on this.)

And finally, you have to communicate the data. How do you share wastewater results with the public in a way that is clear, real-time, local—and acknowledging necessary caveats? This is a tough challenge that health agencies across the U.S. are just starting to tackle, in tandem with the private companies that work on wastewater analysis.

As I said in the radio story accompanying my piece, I hope that, someday, we can get wastewater surveillance updates as easily and regularly as we get weather updates. That future feels a long way off right now, but I intend to keep reporting on the journey in 2023.

If you live somewhere with a thriving (or faltering) wastewater surveillance program, reach out and tell me about it!