In the past week (April 13 through 19), the U.S. officially reported about 94,000 new COVID-19 cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 13,000 new cases each day

- 7% fewer new cases than last week (April 6-12)

In the past week, the U.S. also reported about 12,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,700 new admissions each day

- 3.7 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 8% fewer new admissions than last week

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 1,200 new COVID-19 deaths (170 per day)

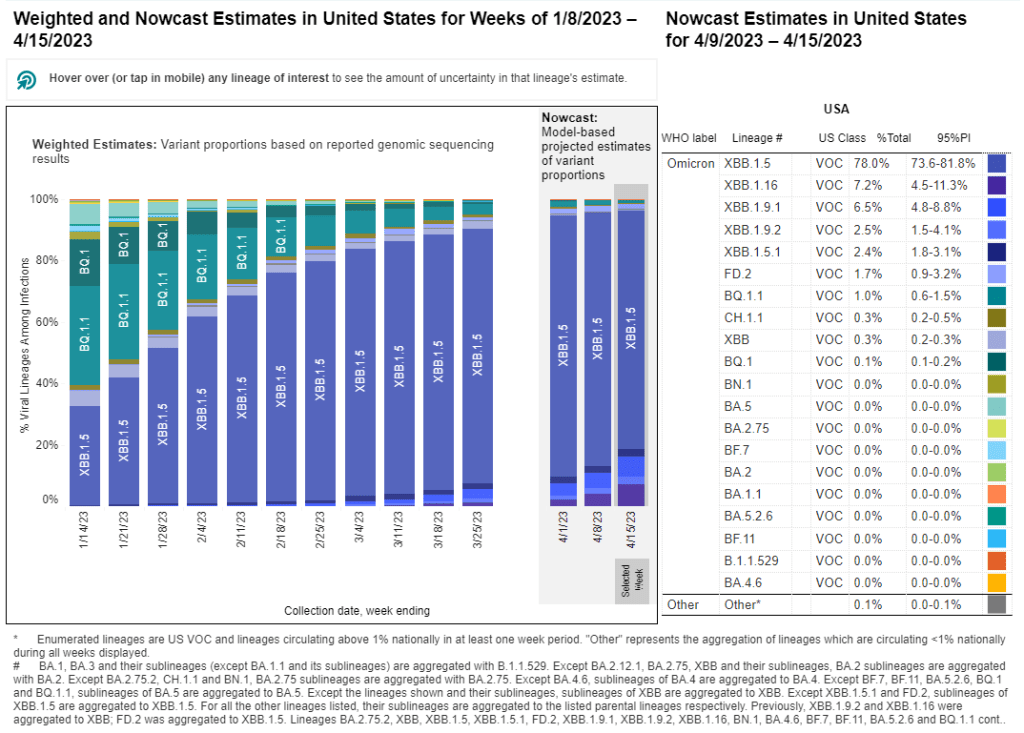

- 74% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 11% by XBB.1.9; 10% by XBB.1.16 (as of April 22)

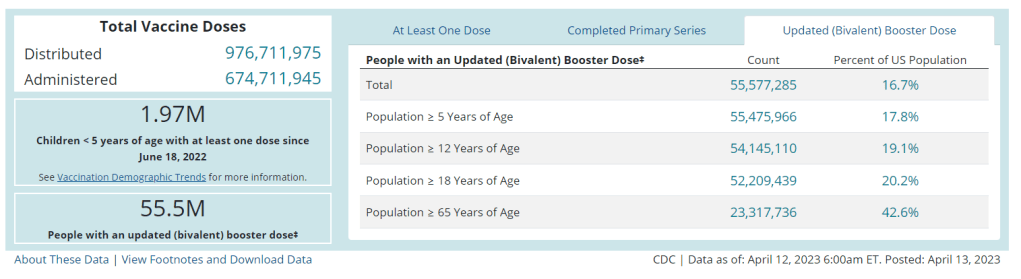

- An average of 35,000 vaccinations per day

Across the U.S., COVID-19 spread continues at a moderately high plateau as newer versions of Omicron compete with XBB.1.5. Officially-reported cases and new hospitalizations declined by 7% and 8% respectively, compared to the prior week.

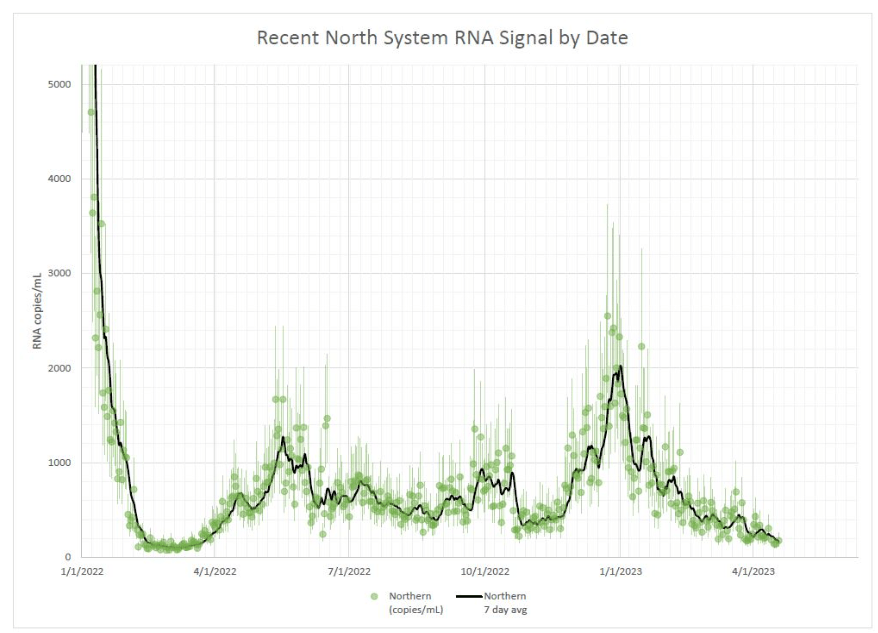

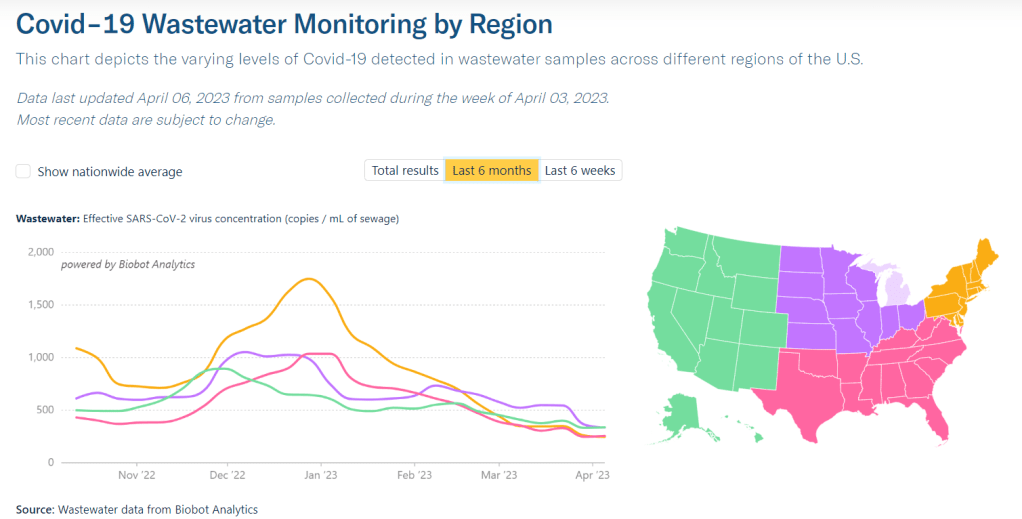

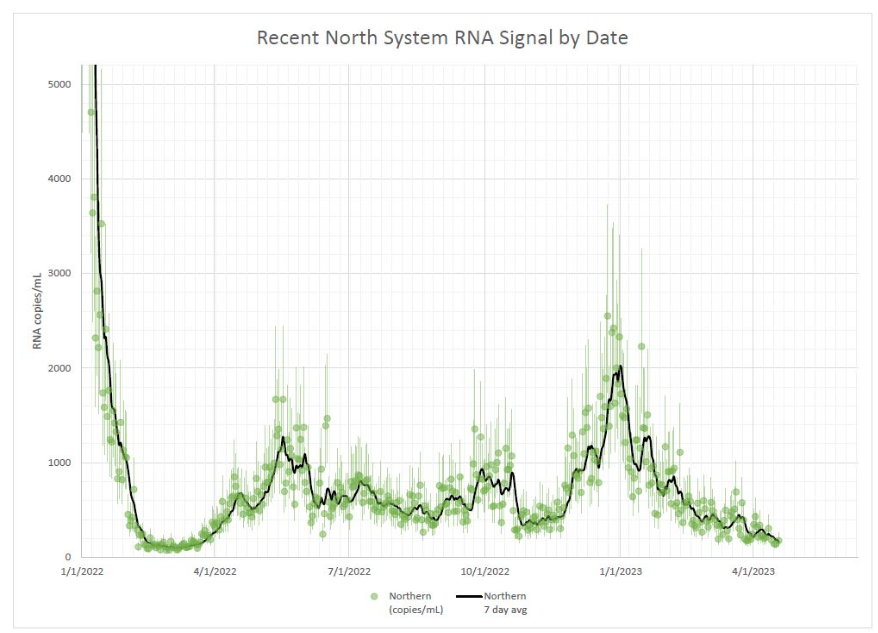

Wastewater surveillance data from Biobot and from the CDC similarly show that COVID-19 spread is at a plateau. Nationally, coronavirus concentrations in sewage are higher than they were at this point in 2021 (when the initial vaccine rollout was in full swing), but lower than at this point in 2022 (when BA.2 had started spreading widely).

Of course, it’s important to flag that official case counts are becoming even more unreliable these days, as PCR testing becomes increasingly difficult to access and state health departments no longer prioritize timely reporting to the CDC. According to CDC, five states didn’t report COVID-19 cases and deaths last week: Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania. (Iowa has permanently stopped reporting.)

These case reporting issues are likely to continue—and perhaps accelerate—when the federal public health emergency ends next month. I’m thinking about how to adjust these National Numbers reports when that happens; that will likely involve foregrounding wastewater data and hospitalizations rather than cases.

Regionally, Biobot’s surveillance shows a slight uptick in coronavirus spread on the West Coast and declines in the other major regions. Some counties in California have reported recent increases in wastewater, according to Biobot and WastewaterSCAN, but it’s currently tough to tell if this is a sustained surge or isolated outbreaks.

The West Coast and Midwest continue to be hotspots for newer versions of Omicron, according to the CDC’s estimates, with XBB.1.9 still most prevalent by far in the region including Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska. Nationwide, the CDC estimates that XBB.1.9 caused about 11% of new cases in the last week and that XBB.1.16 caused 10% of new cases.

XBB.1.16 (also called “Arcturus”) was recently classified as a variant of interest by the World Health Organization because it can spread significantly faster than other Omicron lineages. The variant is likely to “spread globally and contribute to an increase in case incidence,” according to the WHO.

While I’m wary of the new variants, I have been heartened to see coronavirus levels in wastewater remain mostly at plateaus—or even decline—in many places across the U.S. In Boston, for example, coronavirus levels have been on a downward trend since early 2023. I hope to see this trend continue.