- New funding from CDC’s forecasting center: The CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Analytics (CFA) announced a new funding opportunity for state and local health agencies to develop new disease modeling tools. CFA is a relatively new center itself; it launched last year with the goal of modernizing the U.S.’s disease forecasting capacities (see my FiveThirtyEight article about the center for more details). This funding opportunity will, I expect, enable the CFA’s growing staff to work directly with health agencies on advancing analytical methods. I look forward to seeing the results of those projects.

- Experts argue to keep masks in healthcare: A new commentary article, published this week in the Annals of Internal Medicine, argues in favor of keeping mask requirements in healthcare settings. The experts (from the National Institutes of Health and George Washington University) point to real-world experience, suggesting transmission between patients and healthcare workers is less likely when everyone is wearing a mask, preferably one of high quality. This article coincides with an advocacy campaign to keep masks in healthcare, including virtual and in-person actions across the U.S.

- CDC releases provisional drug overdose data for 2022: The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics has released overdose data for 2022, reporting that nearly 110,000 Americans died of overdoses for the second year in a row. Overdoses have leveled off from 2021, but the 2022 data still represent a sharp increase from pre-pandemic trends. Some states in the South and West Coast (such as Texas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Washington) saw the sharpest increases from 2021 to 2022, according to the CDC. These data are all preliminary and will be updated later in the year.

- Pediatric COVID-19 boosters could save school days: A new modeling study, published this week in JAMA Network Open, suggests that the U.S. could have seen about 10,000 fewer kids hospitalized with COVID-19 and 5.5 million fewer school days lost during the 2022-2023 respiratory virus season, if kids received booster shots in large numbers. The researchers arrived at these estimates through a model that simulated COVID-19 booster vaccination rates at similar levels to annual flu vaccination in kids. Future booster campaigns should focus on children in addition to older adults, the authors argue.

- RSV vaccine for infants moves ahead: Speaking of pediatric vaccinations: the FDA’s vaccine advisory committee met last week to discuss a new vaccine candidate from Pfizer, which would protect infants from RSV. Unlike most pediatric vaccines, this shot would be delivered to pregnant parents in order to protect their babies at birth. While the FDA’s advisors endorsed the vaccine for its effectiveness, some committee members expressed concerns over safety. Helen Branswell at STAT has more details.

Author: Betsy Ladyzhets

-

Sources and updates, May 21

-

National numbers, May 21

According to wastewater data from Biobot, COVID-19 spread right now is lower than at this time last year, but higher than the prior two years. In the past week (May 7 through 13), the U.S. reported about 9,200 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,300 new admissions each day

- 2.8 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 5% fewer new admissions than last week (April 30-May 6)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- A 4% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of May 17, per Biobot’s dashboard)

- 64% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 13% by XBB.1.9; 14% by XBB.1.16 (as of May 13)

- An average of 75,000 vaccinations per day

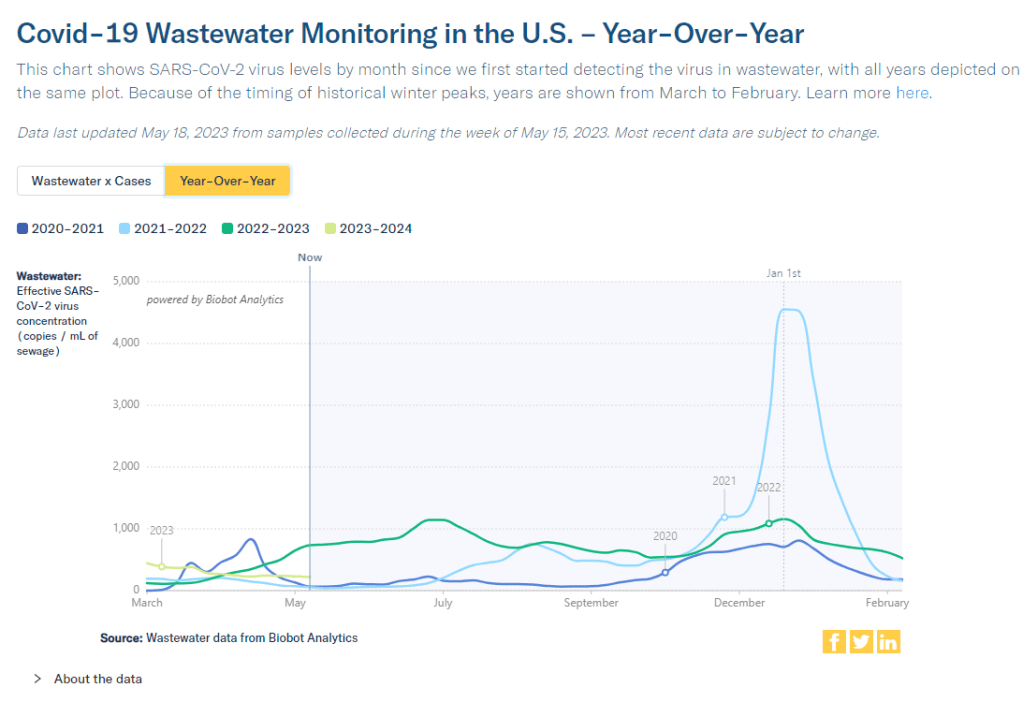

Nationwide, COVID-19 spread in the U.S. continues to be in a somewhat-middling plateau: lower than the massive amount of Omicron transmission we all got used to throughout late 2022, but still higher than the lulls between outbreaks we saw in prior years.

Biobot’s national wastewater surveillance offers a helpful visual for this comparison. As of May 20, the company calculates a national average of 221 viral copies per milliliter of sewage (a common unit for quantifying SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater), based on hundreds of sewage testing sites in its network.

In late May of last year, when early Omicron offshoots were spreading widely, this value was several times higher: 736 viral copies per milliliter. But around the same time in 2021 (when millions of Americans were getting their first vaccine shots) or 2020 (when the very first big surge had ended), wastewater concentrations were under 100 viral copies per milliliter.

It’s also important to note that wastewater concentrations have been fairly level for a couple of months now, both nationally and for all four major regions. High immunity across the population and a lack of divergent new variants have kept us from seeing a new surge since the 2022 winter holidays; but without widespread safety measures, I suspect we’re unlikely to see a drop in transmission below the current baseline.

Hospital admissions, now the CDC’s primary metric for tracking this disease, show a similar picture to the wastewater data. Numbers are low and ticking ever-so-slightly downward, but they’re not zero: about 1,300 people were admitted to hospitals with COVID-19 each day in the week ending May 13.

Deaths with COVID-19 also remain at low yet significant numbers. While the CDC reports only 281 deaths in the last week, this information is now presented with a greater delay than during the federal public health emergency, as the agency had to switch from death reports received directly from states to death certificate data. For the week ending May 6, the CDC revised its number up from about 300 to 622 COVID-19 deaths.

There are no changes to variant estimates this week, as the CDC is now updating that data every other week rather than weekly. XBB.1.5 remains the dominant variant, with XBB.1.16 and XBB.1.19 slowly gaining ground.

Overall, it’s getting harder to identify detailed COVID-19 trends, but a lot of data still do remain available. I’ll keep providing updates as best I can.

-

COVID source shout-out: Wastewater testing at the San Francisco airport

A few months ago, I wrote about how testing sewage from airplanes could be a valuable way to keep tabs on the coronavirus variants circulating around the world. International travel is the main way that new variants get from one country to another, so monitoring those travelers’ waste could help health officials quickly spot—and respond to—the virus’ continued mutations.

This spring, San Francisco International Airport became the first in the U.S. to actually start doing this tracking; I covered their new initiative for Science News. The airport is working with the CDC and Concentric, a biosecurity and public health team at the biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks, which already collaborates with the agency on monitoring travelers through PCR tests.

The San Francisco airport started collecting samples on April 20, and scientists at Concentric told me that they’re happy with how it’s going so far. Airport staff are collecting one sample each day, with each one representing a composite of many international flights. Parsing out the resulting data won’t be easy, but the scientists hope to learn lessons from this program that they can take to other surveillance projects.

Both scientists at Concentric and outside experts are also excited about the potential to monitor other novel pathogens through airplane waste (though the San Francisco project is focused on coronavirus variants right now). Read my Science News story for more details!

-

Sources and updates, May 14

- CDC updates ventilation guidance: On Friday, the CDC made its first-ever official air quality recommendation for all indoor spaces, in an update to its overall ventilation guidance. The agency now says all buildings should strive for five air changes per hour (ACH) at a minimum; in other words, clean air should circulate through the space every 12 minutes or more. This update is a victory for many clean air advocates who’ve pushed for better guidelines during the pandemic as a way to reduce the risk of COVID-19 and other respiratory pathogens. As expert and advocate Devabhaktuni Srikrishna said to me on Twitter: “This is exactly the clarity we were pushing CDC for for since last year… Now the question becomes, how does everyone do it in their home, school, and office? How much does it cost? Where do you get it?”

- Millions Missing in Washington, D.C.: On Friday, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long COVID patient advocates held a demonstration at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to show U.S. leaders how chronic disease has pulled millions of Americans out of public life. The demonstration, organized by ME Action and Body Politic, included an installation of 300 cots with hand-made pillowcases created by patients across the country. Each cot is intended to represent people who can no longer work or do other day-to-day activities that were routine before they got sick with Long COVID or a similar chronic illness. You can learn more by watching ME Action’s press conference from the demonstration.

- Post-PHE prices for COVID-19 testing: Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation put together a new report describing how much Americans will likely pay for PCR and at-home tests now that the federal government no longer supports blanket insurance coverage. At-home test prices range from $6 to $25 per test, depending on the brand and number of tests purchased at once, the KFF analysis found based on a variety of data sources. PCR tests and others performed in healthcare settings range from $25 to $150 per test, with medians around $50. Tests including COVID-19 and other pathogens are the priciest.

- Sleep apnea and Long COVID risk: A new paper, published this week in the journal SLEEP, finds that people with sleep apnea have a higher risk of developing Long COVID compared to those who don’t have this condition. Researchers at New York University (and other institutions) compared Long COVID symptoms among adults and children with and without sleep apnea through multiple electronic health record databases, finding people with sleep apnea had up to a 75% higher risk of long-term COVID-19 symptoms. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER initiative. Like other papers to come out of RECOVER (including another recent study looking at comorbidities), it’s utilized health records rather than the actual cohort of patients recruited into the NIH’s research program.

- Diagnosing COVID-19 through breath: Another notable recent paper, published in the Journal of Breath Research in April: researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology have found they can identify whether a patient has COVID-19 by testing their breath. The technique involves using sensitive lasers and artificial intelligence to differentiate between chemicals in a patient’s breath; it’s similar to a breathalyzer for alcohol testing, though more complicated. In addition to COVID-19, breath testing might help identify other diseases.

-

The CDC’s new COVID-19 dashboard hides transmission risk

The CDC’s new COVID-19 dashboard suggests that the national situation is totally fine, because hospitalizations are low. But is that correct? On Thursday, the CDC revamped its COVID-19 dashboard in response to changing data availability with the end of the federal public health emergency. (For more details on the data changes, see my post from last week.) The new dashboard downplays continued COVID-19 risk across the U.S.

Overall, the new dashboard makes it clear that case counts are no longer available, since testing labs and state/local heath agencies aren’t sending those results to the CDC anymore. You can’t find case counts or trends on the homepage, at the top of the dashboard, or in a county-level map.

Instead, the CDC is now displaying data that shows some of COVID-19’s severe impacts— hospitalizations and deaths—without making it clear how widely the virus is still spreading. Its key metrics are new hospital admissions, currently-hospitalized patients, emergency room visits, and the percentage of recent deaths attributed to COVID-19. You can find these numbers at national and state levels in a revamped “trends” page, and at county levels in a “maps” page.

The “maps” page with county-level data has essentially replaced the CDC’s prior Community Level and Transmission Level page, where users were previously able to find COVID-19 case rates and test positivity rates by county. In fact, as of May 13, the URL to this maps page is still labeled as “cases” when you click into it from the main dashboard.

While these changes might be logical (given that case numbers are no longer available), I think the CDC’s design choices here are worth highlighting. By prioritizing hospitalizations and deaths, the CDC implicitly tells users of this dashboard that the virus should no longer be a concern for you unless you’re part of a fairly small minority of Americans at high risk of those severe outcomes.

But is that actually true, that COVID-19 is no longer a concern unless you’re going to go to the hospital? I personally wouldn’t agree. I’d prefer not to be out sick for a week or two, if I can avoid it. And I’d definitely like to avoid any long-term symptoms—or the long-term risks of heart problems, lung problems, diabetes, etc. that may come after a coronavirus infection.

These outcomes still persist after a mild COVID-19 case. But the current CDC data presentation makes it hard to see those potential outcomes, or your risk of getting that mild COVID-19 case. The agency still has some data that can help answer these questions (wastewater surveillance, variant surveillance, Long COVID survey results, etc.) but those numbers aren’t prioritized to the same degree as hospitalizations and deaths.

I’m sure the CDC data scientists behind this new dashboard are doing the best they can with the information they have available. Still, in this one journalist’s opinion, they could’ve done more to make it clear how dangerous—and how widely prevalent—COVID-19 still is.

For other dashboards that continue to provide updates, see my list from a few weeks ago. I also recommend looking at your state and local public health agencies to see what they’re doing in response to the PHE’s end.

More federal data

-

Ending emergencies will lead to renewed health equity issues

The header image from a story I recently had published in Amsterdam News about declining access to COVID-19 services. Last week, I gave you an overview of the changes coming with the end of the federal public health emergency (PHE), highlighting some shifts in publicly available COVID-19 services and data. This week, I’d like to focus on the health equity implications of the PHE’s end.

COVID-19 led the U.S. healthcare system to do something unprecedented: make key health services freely available to all Americans. Of course, this only applied to a few specific COVID-related items—vaccines, tests, Paxlovid—and people still had to jump through a lot of hoops to get them. But it’s still a big deal, compared to how fractured our healthcare is for everything else.

The PHE allowed the U.S. to make those COVID-19 services free by giving the federal government authority to buy them in bulk. The federal government also provided funding to help get those vaccines, tests, and treatments to people, through programs like mass vaccination sites and mobile Paxlovid delivery. Through these programs, healthcare and public health workers got the resources to be creative about breaking down access barriers.

Now that the emergency is ending, those extra supplies and resources are going away. COVID-19 is going to be treated like any other disease. And as a result, people who are already vulnerable to other health issues will become more at risk for COVID-19.

I wrote about this health equity problem in a recent story for Amsterdam News, a local paper in New York City that serves the city’s Black community. The story talks about how COVID-19 services in NYC are changing with the end of the PHE, and who will be most impacted by those changes. It’s part of a larger series in the paper covering the PHE’s end.

Most of the story is NYC-specific, but I wanted to share a few paragraphs that I think will resonate more widely:

Jasmin Smith, a former contact tracer who lives in Brooklyn, worries that diminished public resources will contribute to increased COVID-19 spread and make it harder for people with existing health conditions to participate in common activities, like taking the subway or going to the grocery store.

COVID-19 safety measures “make the world more open to people like myself who are COVID-conscious and people who might be immunocomprmised, disabled, chronically ill,” Smith said. “When those things go away, your world becomes smaller and smaller.”

The ending federal public health emergency has also contributed to widespread confusion and anxiety about COVID-19 services, [said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, a professor of epidemiology and global health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health]. “People have so many questions about this transition,” she said, and local leaders could do more to answer these questions for New Yorkers.

The near future of COVID-19 care in the U.S. could reflect existing health disparities for other endemic diseases, like the seasonal flu and HIV/AIDS, [said Steven Thrasher, a professor at Northwestern University and author of the book, The Viral Underclass]. For example, people with insurance and a primary care physician are more likely to get their annual flu shots, he said, while those without are more likely to face severe outcomes from the disease.

After May 11, COVID-19 outcomes are likely to fall along similar lines. “More people have died of AIDS after there were HIV medications,” Thrasher said. “More people have died of COVID when there were vaccines in this country than before.”

For more news and commentary on COVID-19 emergencies ending, I recommend:

- Other stories in Amsterdam News’ The Long Emergency series

- Only the Global-Health Emergency Has Ended (The Atlantic)

- Does the end of Covid emergency declarations mean the pandemic is over? (STAT News)

- End of PHE: A shift in data (Your Local Epidemiologist)

- The Sociological Production of the End of the Pandemic (Death Panel)

-

National numbers, May 14

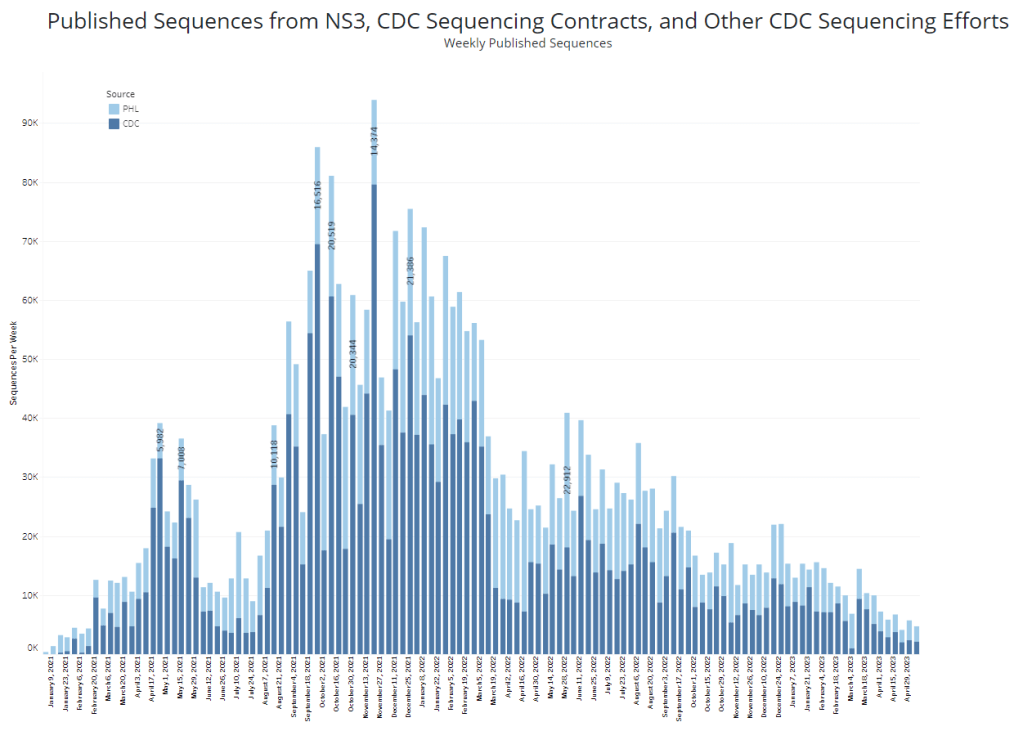

The CDC and its partners are sequencing far fewer coronavirus samples than they have at prior periods of the pandemic, making it harder to spot new variants of concern. In the past week (April 30 through May 6), the U.S. reported about 9,500 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,400 new admissions each day

- 2.9 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 7% fewer new admissions than last week (April 22-29)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- A 14% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of May 10, per Biobot’s dashboard)

- 64% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 13% by XBB.1.9; 14% by XBB.1.16 (as of May 13)

- An average of 70,000 vaccinations per day

COVID-19 spread continues to trend down in the U.S., though our data for tracking this disease is now worse than ever thanks to the end of the federal public health emergency. If newer Omicron variants cause a surge this summer, those increases will be hard to spot.

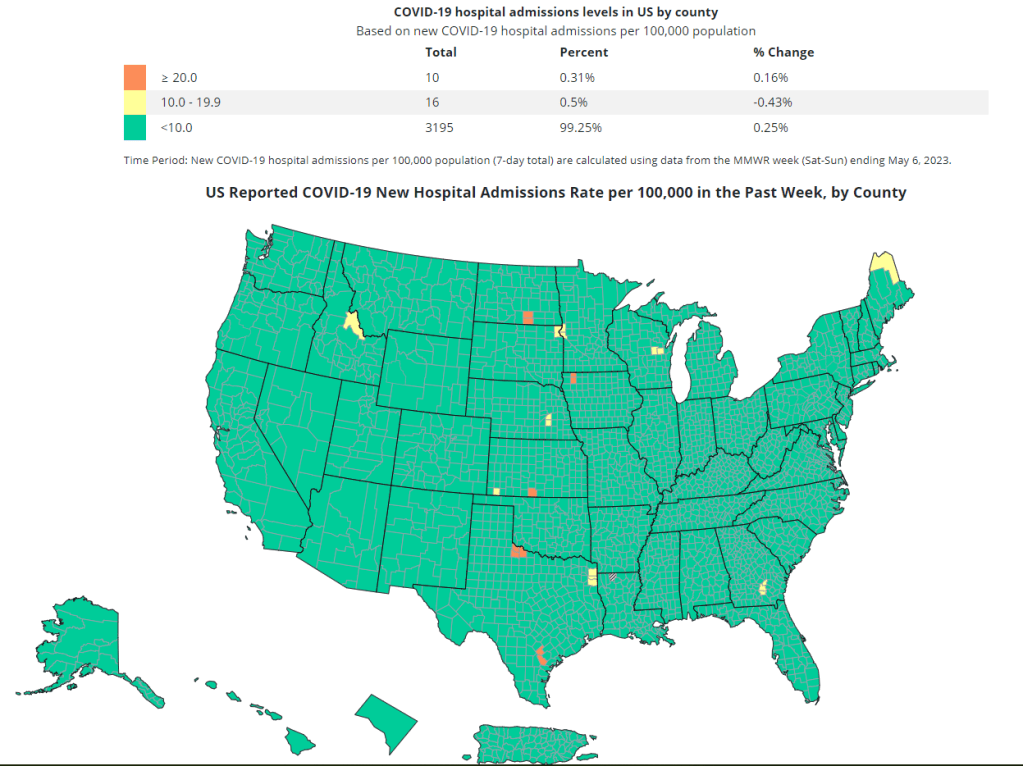

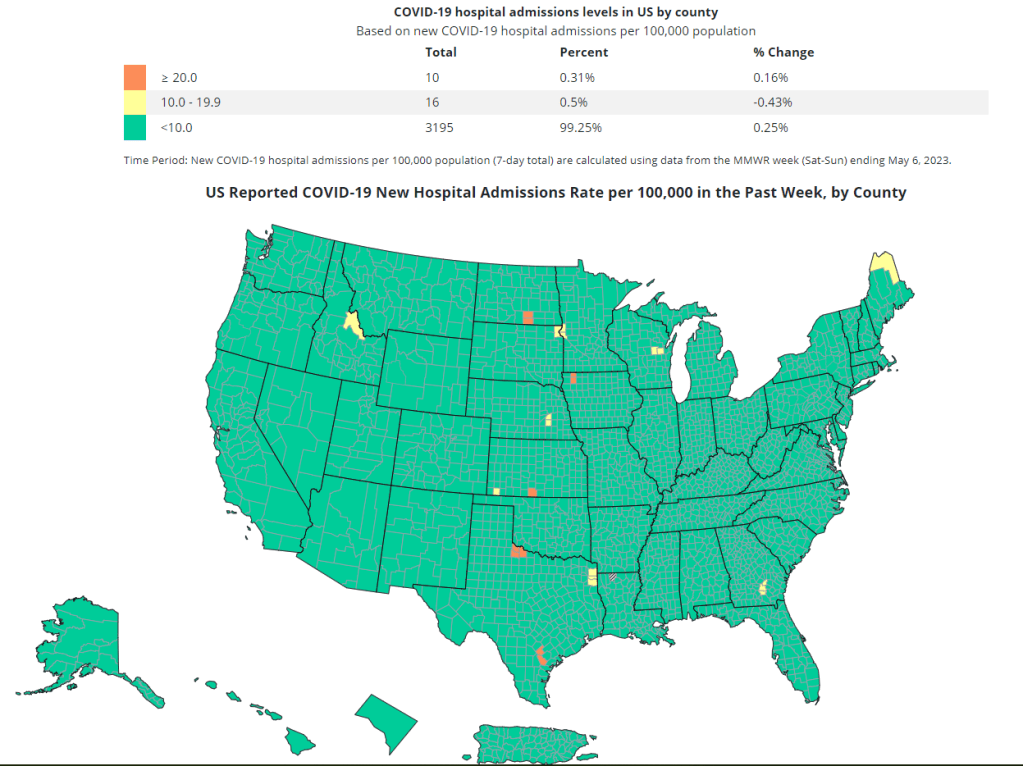

As a result of the PHE’s conclusion this week, the CDC is no longer collecting national case counts or testing data. Instead, the agency now recommends using hospitalization data to monitor how hard COVID-19 is hitting your community—even though this metric typically lags behind actual infection patterns—while variant data and wastewater surveillance may provide warnings about new surges.

My national updates will take a similar approach. This week, hospital admissions continue their national plateau, with a decrease of about 7% from the week ending April 29 to the week ending May 6. The CDC’s national map show that admissions are low across the country, with 99% of counties reporting fewer than 10 new admissions per 100,000 residents.

Wastewater surveillance also suggests that, while there’s still a lot of COVID-19 in the U.S., disease spread is still on a plateau or slight decline in most of the country. Biobot’s data show a minor national downturn in recent weeks; trends are similar across the four major regions, though the decline is a bit steeper on the West Coast.

The variant picture also hasn’t changed much: XBB.1.5 caused about two-thirds of new cases in the last two weeks, according to the CDC’s estimates. XBB.1.6 caused about 14% and XBB.1.9 caused 13%; these newer versions of Omicron are gaining ground, but fairly slowly. Regionally, XBB.1.6 is most prevalent in the Northeast and on the West Coast, while XBB.1.9 is most prevalent in the Midwest.

It’s worth noting, though, that the CDC has switched its variant reporting from weekly to every other week, as fewer patient specimens are going through sequencing for variant identification. The agency and its surveillance partners are sequencing around 5,000 samples every week, compared to over 80,000 a week at the height of the first Omicron surge.

Limited sequencing efforts will make it harder for the CDC to quickly identify (and respond to) new variants of concern. The same challenge is happening around the world, as PCR tests become less broadly available. Sequencing coronavirus samples from wastewater may help, but that’s only happening in a small subset of sewage testing sites right now.

One last bit of good news: vaccine administration numbers are up in the last couple of weeks, as seniors and other eligible high-risk people get their second bivalent boosters. About 70,000 people received vaccines each day this week, compared to around half that number a few weeks ago. If you’re eligible for a second booster, this is a good time to make an appointment!

-

COVID source callout: Outbreak at a CDC conference

Last week, we learned that a CDC conference—a gathering of experts in the agency’s epidemic intelligence service, no less—led to some COVID-19 cases, thanks to reporting by the Washington Post.

Well, this past Tuesday, the Post published a follow-up story: more than 30 people got sick following the conference, and the CDC is working with the Georgia Department of Health to investigate. The case count was 35 as of Tuesday, and is surely higher now; about 2,000 people attended the conference.

It’s now safe to say that this conference led to an outbreak. And that isn’t a surprising outcome, considering that it didn’t require masks or other COVID-19 safety measures. As I wrote last week, this outbreak basically signifies that the CDC considers ongoing COVID-19 spread at large events normal and unavoidable.

Even though this situation is, in fact, disappointing and could have been avoided with basic safety measures. 🙃

-

Sources and updates, May 7

- KFF Medicaid Unwinding tracker: The Kaiser Family Foundation just published a new tracker detailing Medicaid enrollment by state. Enrollment rose to record levels during the pandemic, as a federal measure tied to the public health emergency forbid states from taking people off the insurance program. Now, states are going through the slow process of evaluating people’s eligibility and taking some off the program, in a process called “unwinding.” The KFF tracker is following this process, presenting both Medicaid enrollment data by state and information on each state’s timeline for evaluation.

- Biden administration ends vaccine mandates: In time with the federal public health emergency’s end, the Biden administration has announced that it will lift its COVID-19 vaccine rules for federal workers and contractors. International travelers to the U.S. also will no longer need to provide proof of their vaccination status, and the administration is working to end requirements for other groups of workers and travelers. This change is, essentially, another signal of the administration giving up on mass vaccination campaigns; after all, most of the people who got their shots under these rules haven’t received an Omicron booster.

- Vaccine protection wanes over time: A new review paper from researchers in Trento, Italy, published this week in JAMA, shows the importance of booster shots for maintaining protection from COVID-19. The researchers compiled and analyzed findings from 40 studies that evaluated vaccine effectiveness. Overall, they found, the protection that both primary series and booster shots provide against an Omicron infection drops significantly by six months and nine months after vaccination. Remember: Americans over 65 and/or immunocompromised, you’re now eligible for another bivalent/Omicron-specific booster.

- Disparities in COVID-19 deaths persist: Two new studies this week examine COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity. The first study, from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, examined deaths of all causes during the pandemic, finding that Black and Native Ameircans had higher death rates than other racial/ethnic groups. COVID-19 was the fourth highest cause of death in 2022, after heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injury. The second study, from Andrew Stokes and collaborators, examined COVID-19 deaths during the U.S.’s first Omicron wave compared to earlier surges, finding that disparities decreased—but only because white deaths went up during the second year of the pandemic.

- Characterizing Long COVID neurological symptoms: Another new study from this week: researchers at the NIH performed detailed examinations of 12 Long COVID patients to better understand their neurological symptoms. The researchers used an approach called “deep phenotyping,” which involves a variety of tests that aren’t typically used in clinical settings. They found that the patients had a number of abnormalities in their immune systems and autonomic nervous systems compared to healthy controls, pointing to different potential drivers of symptoms.

- FDA approves RSV vaccine: Finally, a bit of non-COVID good news: for the first time, the FDA has approved a vaccine for RSV, the seasonal respiratory virus that can cause severe symptoms in older adults and young children. This vaccine, made by GSK, was approved for adults ages 60 and up and will likely get distributed during the next cold/flu season. Scientists have been working on RSV vaccines for decades, making this a major milestone for reducing the disease’s impact. Helen Branswell at STAT has more details.

-

WHO ends the global health emergency for COVID-19

As the U.S. gears up to end its federal public health emergency for COVID-19, the World Health Organization just declared an end to the global health emergency. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced the declaration on Friday, following a meeting of the organization’s COVID-19 emergency committee the day before.

Here’s what this declaration means, pulling from Helen Branswell’s article in STAT News and Katelyn Jetelina’s Your Local Epidemiologist post:

- The world is at a point of transition from considering COVID-19 an unexpected emergency to considering it a part of our daily lives, a disease that we’ll be dealing with in the long term.

- The WHO will have fewer resources for an international response to COVID-19, such as coordinating between countries and sharing data at a global scale.

- The WHO will also have less authority when it comes to issuing international guidance to control COVID-19 spread.

- There will be fewer incentives for countries to accelerate vaccines, treatments, and tests for COVID-19.

The declaration does not mean that COVID-19 is “over.” We have plenty of long-term issues to deal with here: millions suffering from Long COVID, continued COVID-19 waves around the world, potential new variants, healthcare worker shortages, and declines in childhood vaccination rates, to name a few. Tedros may set up a new committee to make recommendations on long-term COVID-19 management, according to Branswell’s article.

In fact, the WHO recently publicized the impacts of Long COVID: Tedros delivered a PSA explaining that one in ten coronavirus infections leads to some form of Long COVID, and suggesting that “hundreds of millions of people will need longer-term care.” Shifting out of the emergency phase of our global COVID-19 response should be a call to action for scientists and health experts to now focus on Long COVID needs.

Still, a lot of people might interpret the WHO’s declaration as an announcement that they no longer need to worry about COVID-19. Some mainstream publications that have covered the change haven’t done a great job of conveying the nuances here, and I’ve already seen some misinterpretation on social media.

COVID-19 may not be an emergency at this point. But we’re probably going to be living with it for the rest of our lives, and there’s a lot of work left to do.

More on international data