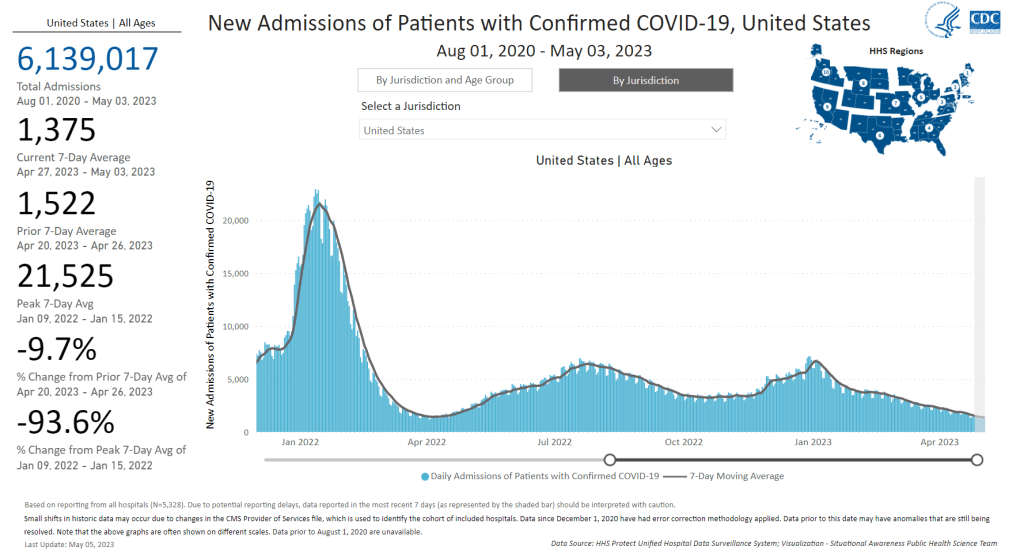

As winter approaches, pretty much every public health expert I follow is anticipating a COVID-19 surge. Experts anticipate that indoor gatherings and travel for the holiday season—with fewer COVID-19 precautions than we had earlier in the pandemic—will lead to more disease spread, just as these behaviors have historically contributed to more spread of flu and other common pathogens this time of year.

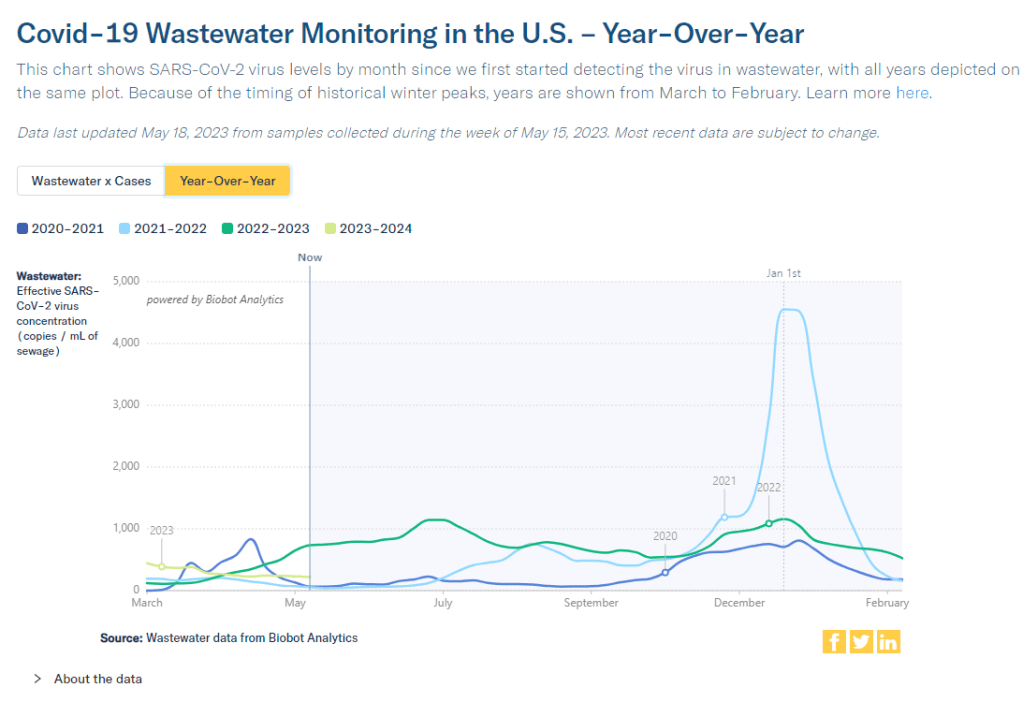

While it seems a surge is likely, the size and severity of that surge may depend in part on SARS-CoV-2 variants. Variants can evolve to more efficiently reinfect people who got COVID-19 recently or to evade our vaccines. These explosive variants can add fuel to the fire when people are already spending a lot of time indoors together with relatively few precautions, as we saw with the original Omicron in winter 2021-22.

As a result, experts are closely watching a few current variants that might lead to faster COVID-19 spread this winter. Here’s a review of what’s circulating right now, what to watch for in the coming weeks, and how our public health system is tracking the variants.

XBB.1.5 and relatives

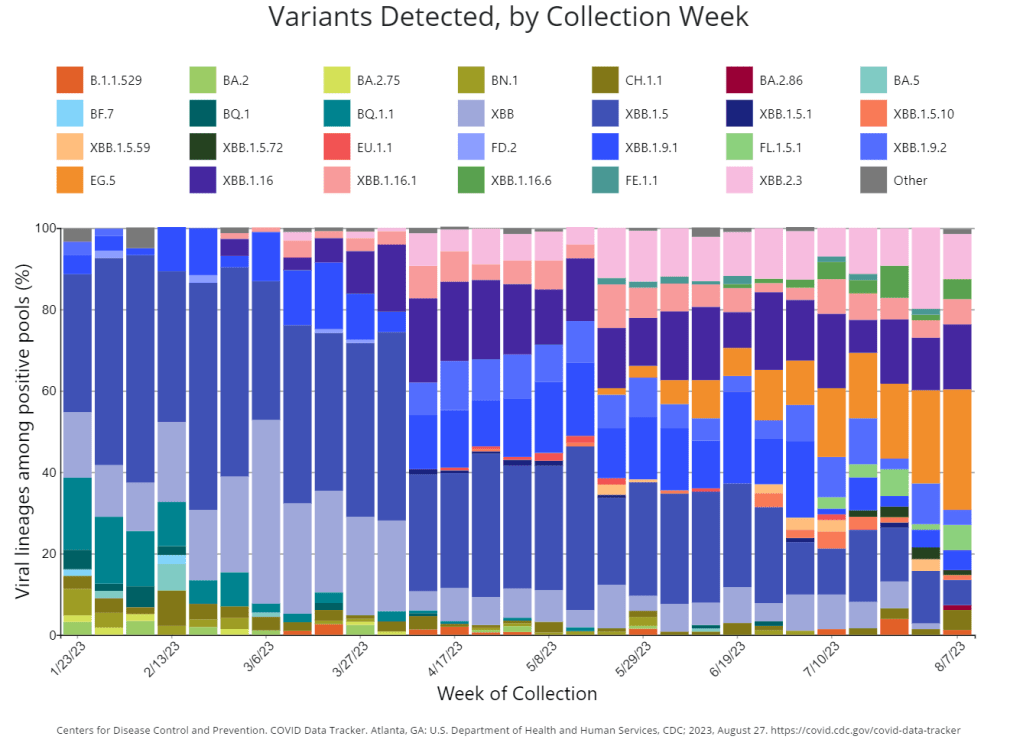

Omicron XBB emerged in late 2022 when two different versions of BA.2, one of the first Omicron lineages, merged together in an evolutionary process called recombination. While the original XBB didn’t really take off globally, it started to mutate as it spread in the U.S., leading to XBB.1.5 in early 2023. See my FAQ post from January for more details.

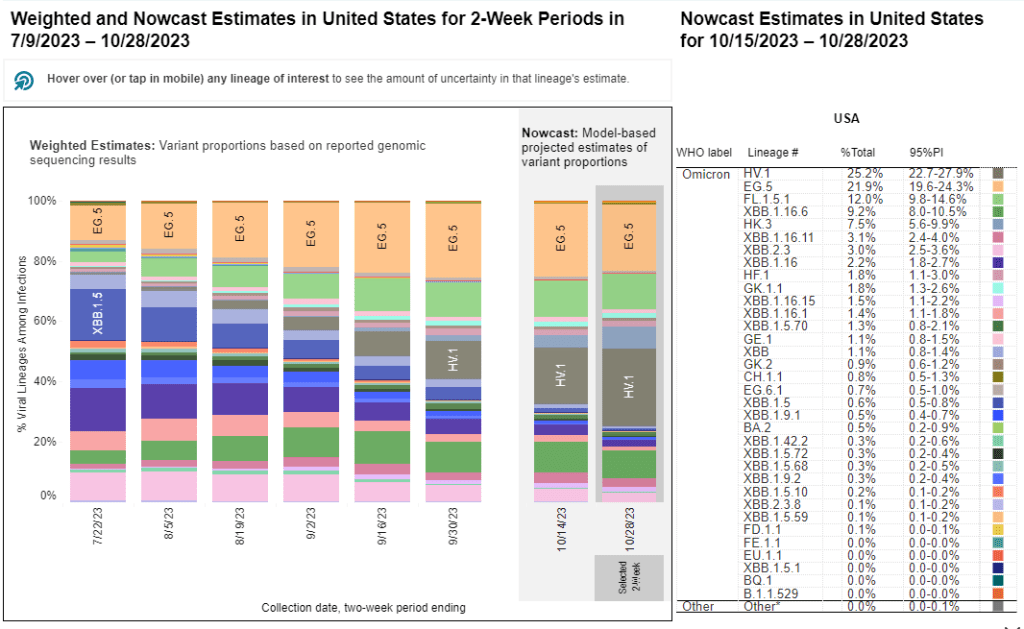

XBB.1.5 has remained a dominant lineage in the U.S. and globally for much of this year. Scientists tracking variants have mostly identified new variants that descend from XBB.1.5, though you might not guess it from the naming schemes which often shorten names for convenience (for example, XBB.1.9.2.5 became EG.5). As a result, the FDA advised vaccine manufacturers to base their COVID-19 shots for this year on XBB.1.5.

EG.5 and FL.5.1

EG.5 and FL.5.1 are two of those XBB.1.5 relatives, descended from the XBB recombinant variant with enough evolutionary steps that virologists gave them these shorthand titles. These two variants are notable because they share a specific mutation, dubbed “FLip,” which helped the variants reinfect people more easily after prior infection or vaccination.

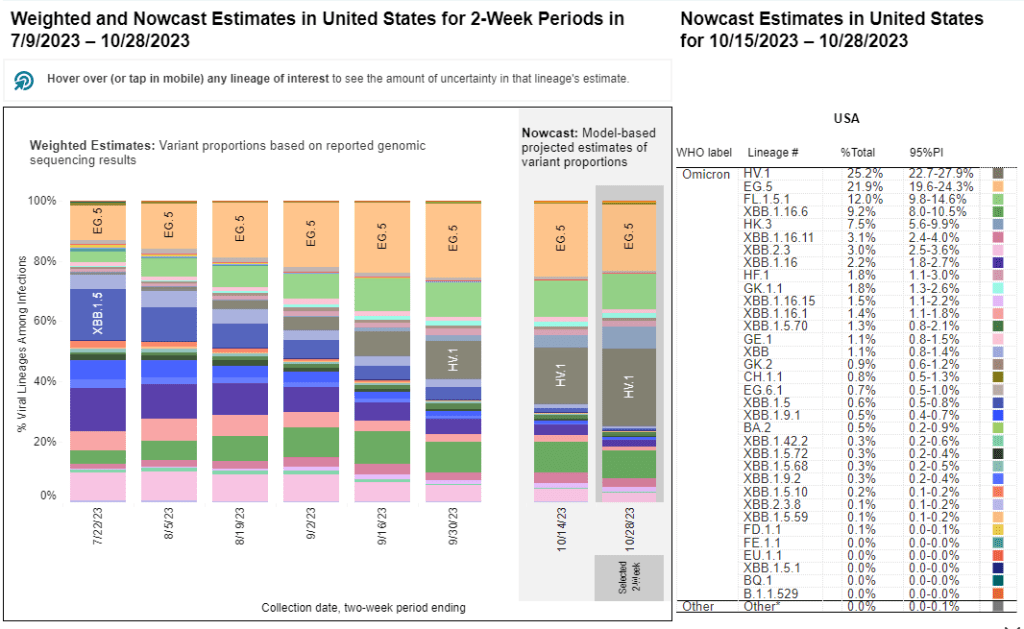

The CDC’s variant surveillance estimates suggest that EG.5 and FL.5.1 have been prominent—but not really dominant—variants in the U.S. this fall. In the CDC’s most recent update, the agency estimates that these variants caused 22% and 12% of cases respectively during the two weeks ending October 28. They don’t appear different enough from other XBB.1.5 relatives to really break through and cause a surge.

HV.1, descendant of EG.5

HV.1 evolved from EG.5, making it another XBB.1.5 relative. It’s the most common variant in the U.S. right now, with the CDC’s latest update estimating that it caused about one in four COVID-19 cases during the last two weeks. Like the other variants discussed above, HV.1 has a slight evolutionary advantage over its relatives; but it’s not significantly different enough to cause a huge surge right now.

BA.2.86

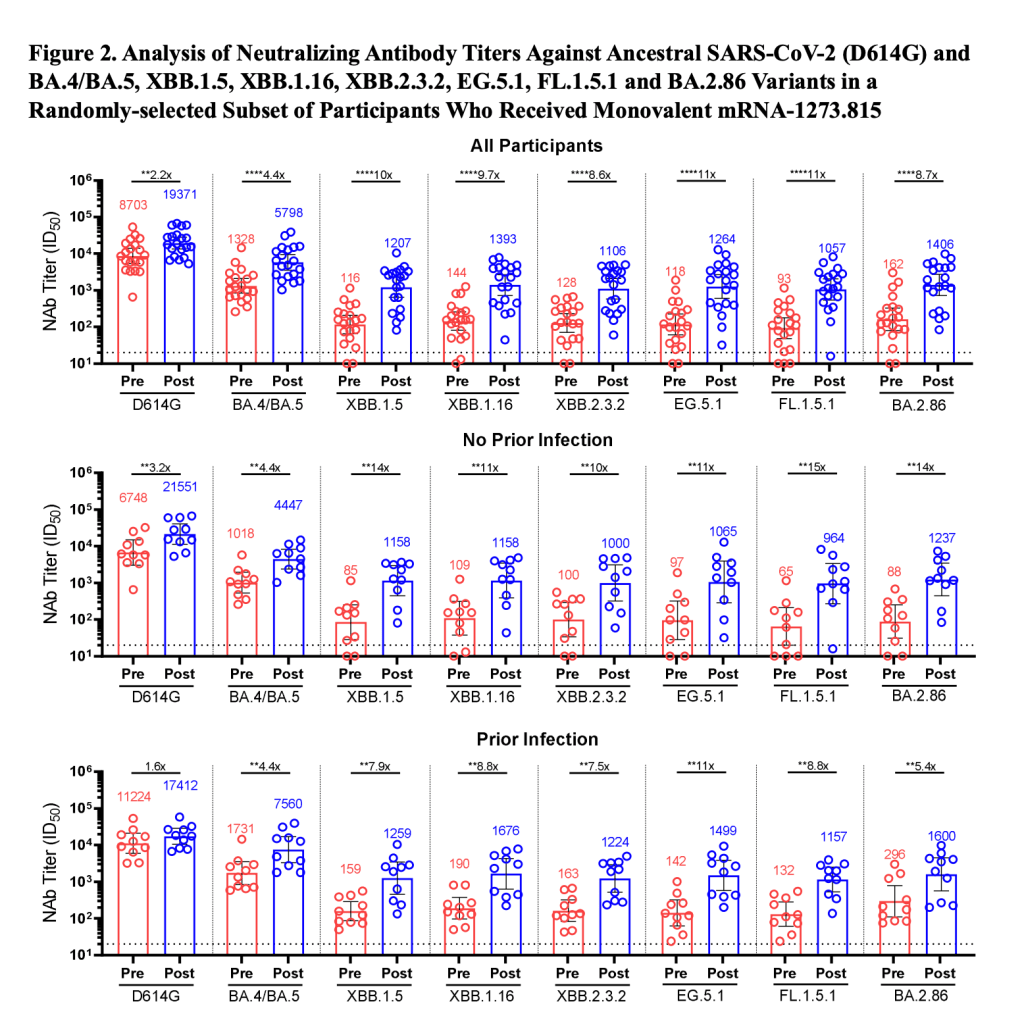

BA.2.86 got some attention when it emerged in August. This variant, unlike the others that have circulated in 2023, is not related to XBB.1.5. Instead, it takes us back in the coronavirus’ evolution, as it evolved directly from BA.2—a version of Omicron that spread widely back in early 2022. Scientists expressed concern about some worrying mutations in BA.2.86 and wondered if our vaccines, matched to XBB.1.5, might not work well against it.

Two months later, BA.2.86 hasn’t spread widely around the world as scientists worried that it might. It doesn’t appear to have a huge advantage over the XBB.1.5 descendants. While CDC surveillance has identified BA.2.86 across the U.S., it’s caused less than 1% of cases, according to the agency’s estimates.

JN.1, descendant of BA.2.86

But BA.2.86 could still indirectly cause some problems: this variant, like all the others, has been mutating. In the last couple of weeks, scientists have started to closely watch one BA.2.86 descendant called JN.1. JN.1 has picked up mutations that make it better at evading immunity from past infections or vaccinations, leading, of course, to faster spread.

Eric Topol describes the global rise of JN.1 in a recent Substack post:

JN.1 has shown up in many countries now, besides France and the UK, including the US, Iceland, Portugal, Belgium, Israel, Spain, Netherlands, Canada Germany, and Singapore. Other derivatives of BA.2.86 such as JN.2 and JN.3 are also being identified in multiple countries.

We won’t know for a few weeks as to whether JN.1 will be linked with a significant rise in COVID or how well our immune response from prior vaccinations, infection(s) and the XBB.1.5 new booster will keep us protected.

So, while BA.2.86 itself may be more benign than expected, JN.1 and its relatives are worth watching. Sequence data shared in the global repository GISAID suggest that this variant is spreading quickly globally, and may be contributing to increased spread in France in particular.

How we’re tracking variants

As I described in my post about BA.2.86, the U.S. has a few ways of tracking variants. The CDC recently highlighted four key surveillance systems in a report about monitoring BA.2.86, published in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report:

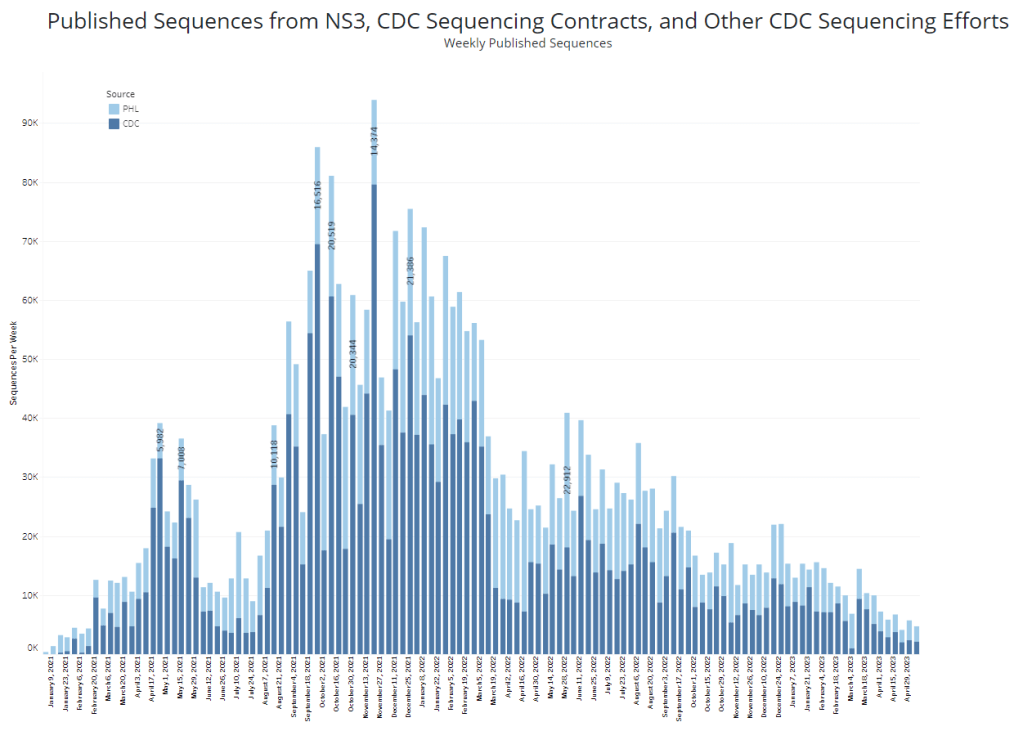

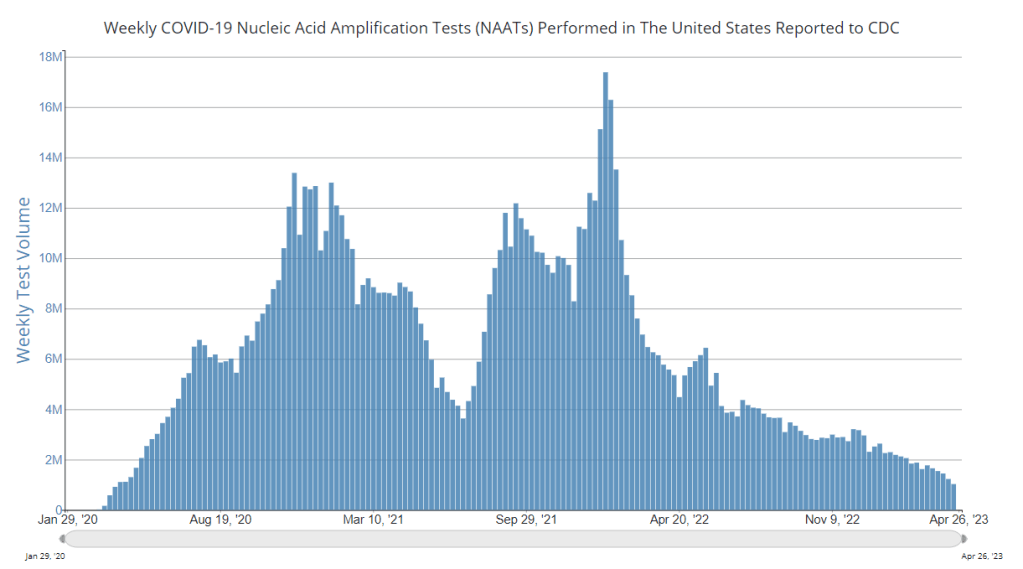

- The national SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program, in which the CDC and commercial partners anonymously select and sequence samples from people who had positive COVID-19 PCR tests;

- The Traveler-based Genomic Surveillance program, in which international travelers returning to U.S. airports can voluntarily get PCR-tested in groups;

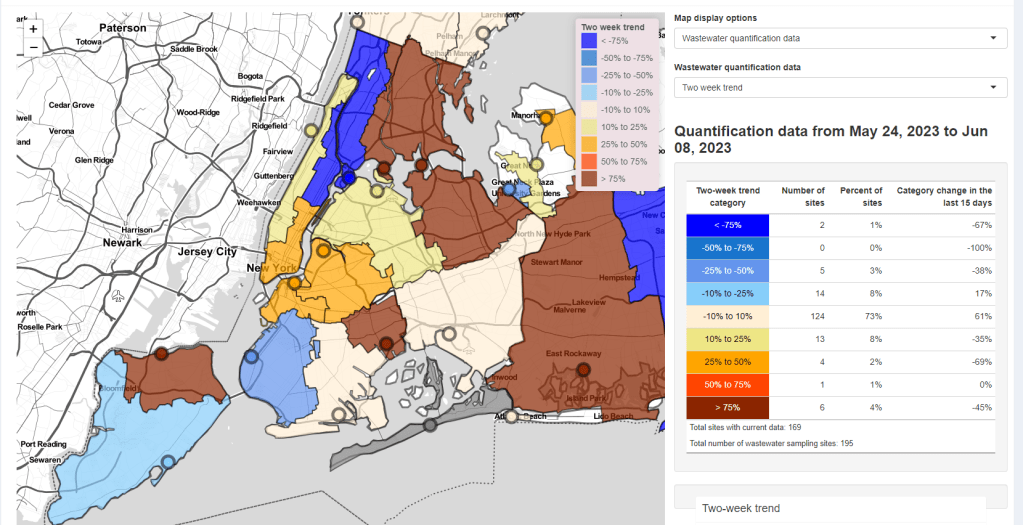

- The National Wastewater Surveillance System, in which some public health labs sequence sewage samples that are part of the CDC’s wastewater surveillance program (with about 400 sewersheds participating in sequencing);

- Digital public health surveillance, using coronavirus sequences that are shared on public, open-source platforms like GISAID.

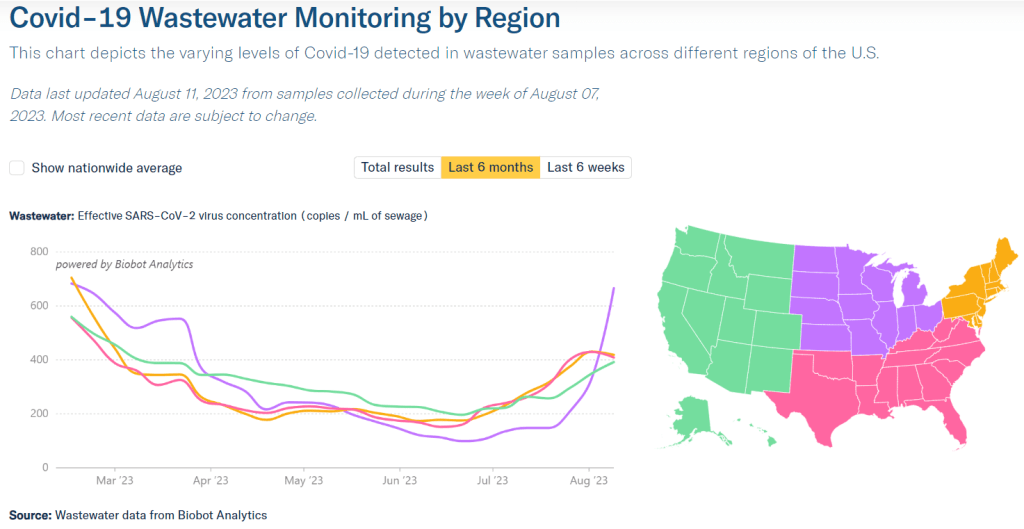

CDC scientists use all four of these systems to keep track of variants circulating in the U.S. Sequencing wastewater samples is particularly important these days with fewer PCR tests available, I argued in a post last month.

Variants don’t happen in isolation

Sometimes, news reports about coronavirus variants cover the virus’ evolution as though it happens in isolation. Like the virus is just mutating in a vacuum, and would do so forever regardless of our human behavior.

But this isn’t accurate. The coronavirus mutates because we keep spreading it, with each infection creating an opportunity for new mutations to arise. If our public institutions really took measures to stop COVID-19 from spreading, it would also be much harder for the virus to keep evolving and evading us.

As variant expert J.P. Weiland pointed out on Twitter: “Timing is so important for impact. If it [JN.1] becomes dominant before the holidays, the wave will be quite a lot bigger than dominance in Jan.”

So, in case you need another motivator to keep up the COVID-19 precautions this holiday season: consider it doing your part to reduce viral evolution.