I have a new story up this week at Science News, describing how the field of wastewater surveillance exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic and is now looking toward other public health threats.

As long-time readers know, wastewater surveillance has been one of my favorite topics to cover over the last couple of years. I’m fascinated by the potential to better understand our collective health through tracking our collective poop—and by all the challenges that this area of research faces, from navigating interdisciplinary collaborations to interpreting a very new type of data to obtaining funding for continued testing.

My story for Science News builds on other reporting I’ve done on this topic and provides a comprehensive overview of the growing wastewater surveillance field, with a particular focus on how research is now going beyond COVID-19. There’s so much potential here that, as I point out in the story, many researchers are asking not, “What can we test for?” but “What should we test for?”

Here’s the story’s introduction; go to Science News for the full article:

The future of disease tracking is going down the drain — literally. Flushed with success over detecting coronavirus in wastewater, and even specific variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, researchers are now eyeing our collective poop to monitor a wide variety of health threats.

Before the pandemic, wastewater surveillance was a smaller field, primarily focused on testing for drugs or mapping microbial ecosystems. But these researchers were tracking specific health threats in specific places — opioids in parts of Arizona, polio in Israel — and hadn’t quite realized the potential for national or global public health.

Then COVID-19 hit.

The pandemic triggered an “incredible acceleration” of wastewater science, says Adam Gushgari, an environmental engineer who before 2020 worked on testing wastewater for opioids. He now develops a range of wastewater surveillance projects for Eurofins Scientific, a global laboratory testing and research company headquartered in Luxembourg.

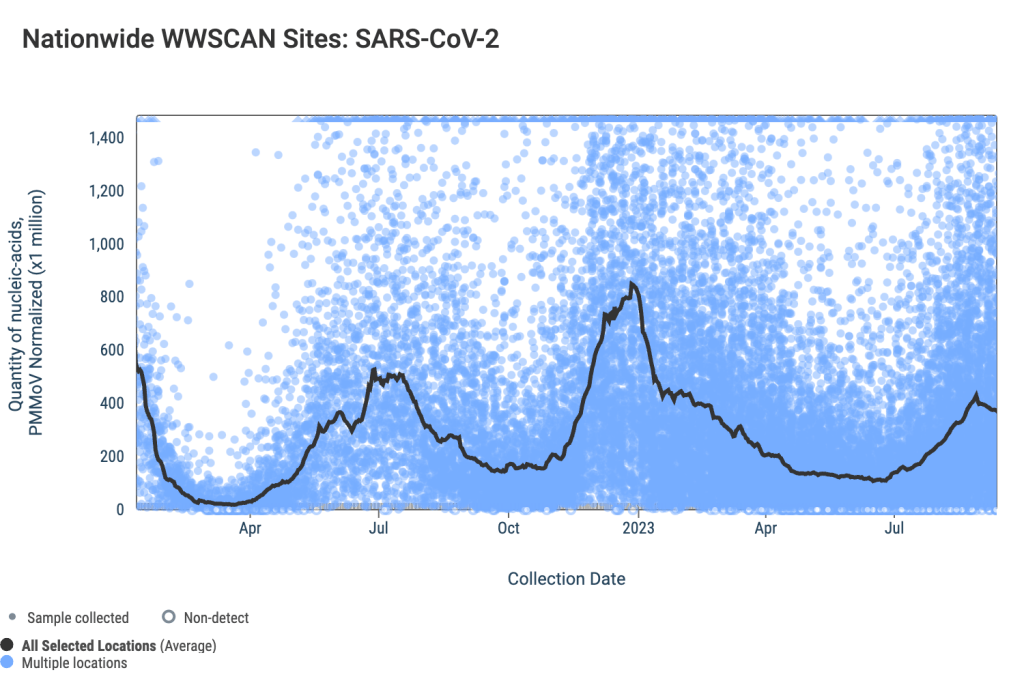

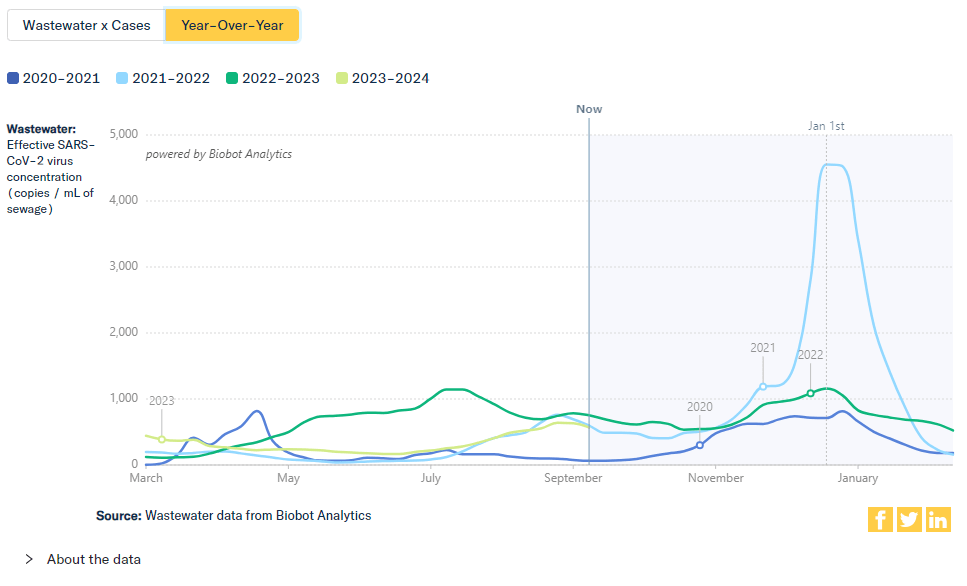

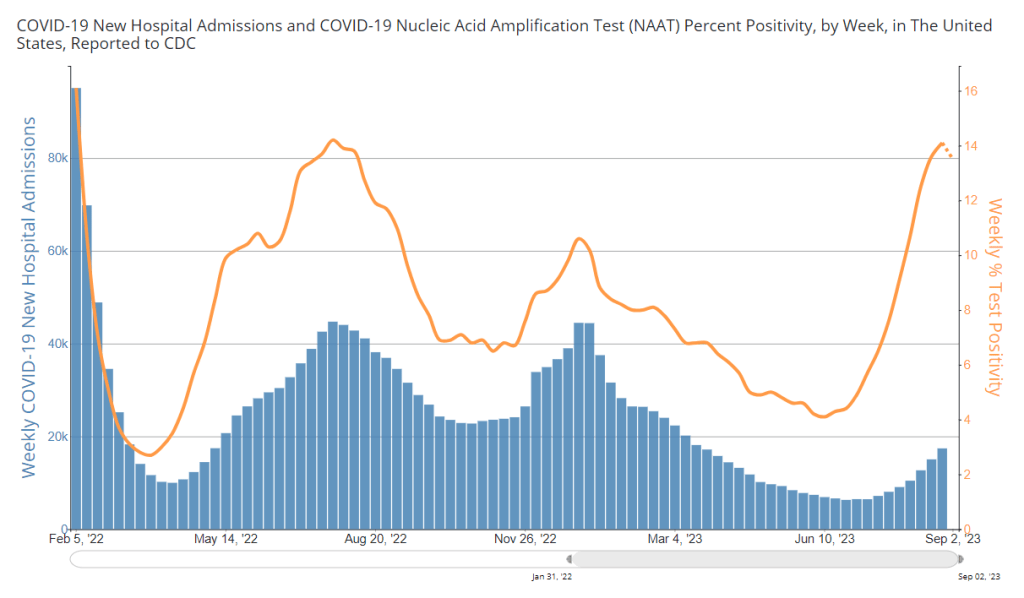

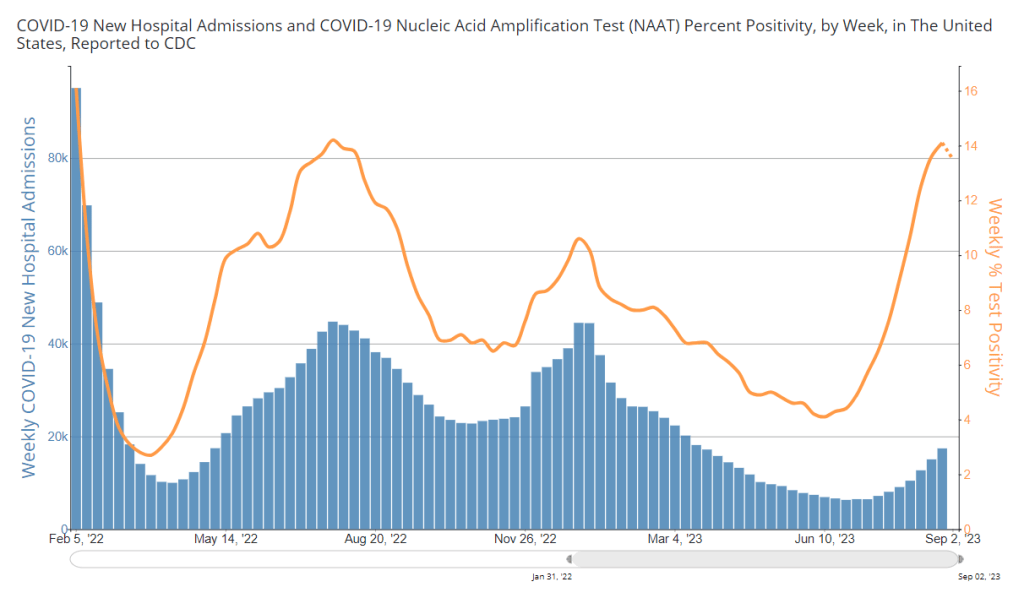

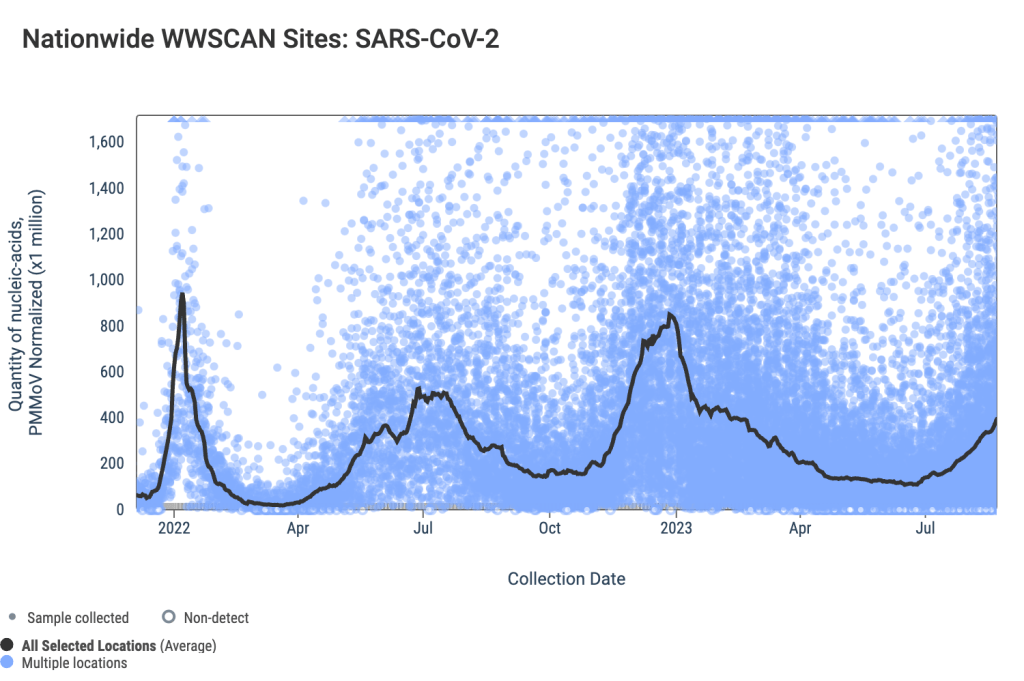

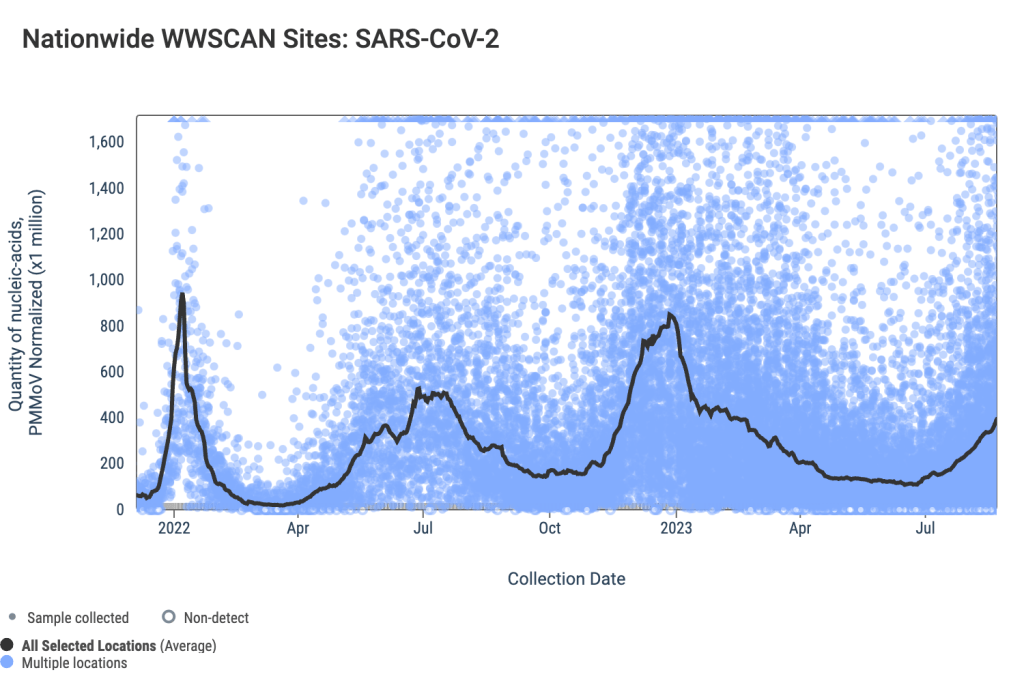

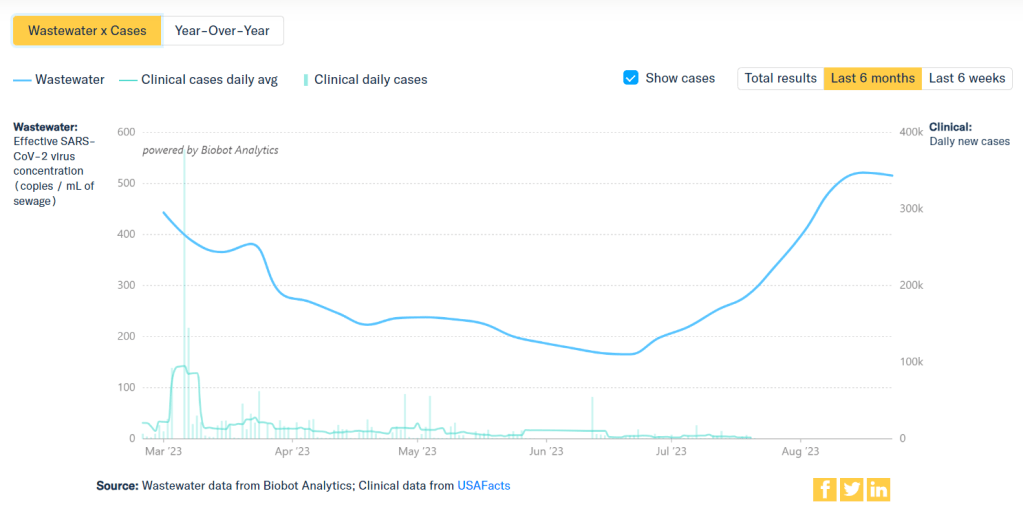

A subfield that was once a few handfuls of specialists has grown into more than enough scientists to pack a stadium, he says. And they come from a wide variety of fields — environmental science, analytical chemistry, microbiology, epidemiology and more — all collaborating to track the coronavirus, interpret the data and communicate results to the public. With other methods of monitoring COVID-19 on the decline, wastewater surveillance has become one of health experts’ primary sources for spotting new surges.

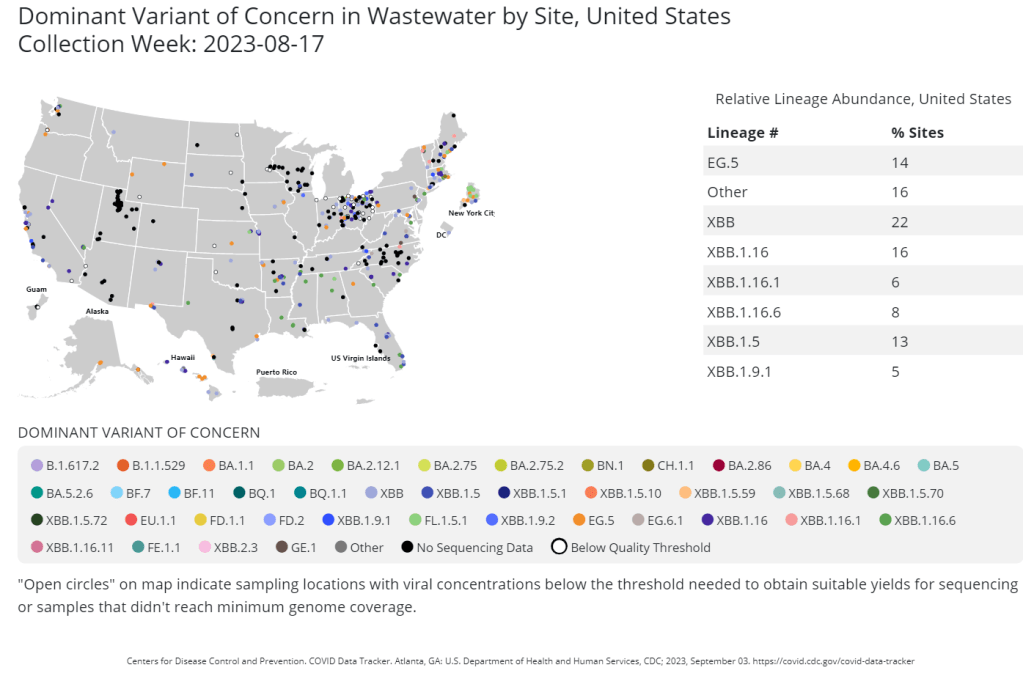

Hundreds of wastewater treatment plants across the United States are now part of COVID-19 testing programs, sending their data to the National Wastewater Surveillance System, or NWSS, a monitoring program launched in fall 2020 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hundreds more such testing programs have launched globally, as tracked by the COVIDPoops19 dashboard run by researchers at the University of California, Merced.

In the last year, wastewater scientists have started to consider what else could be tracked through this new infrastructure. They’re looking at seasonal diseases like the flu, recently emerging diseases like bird flu and mpox, formerly called monkeypox, as well as drug-resistant pathogens like the fungus Candida auris. The scientists are even considering how to identify entirely new threats.

Wastewater surveillance will have health impacts “far broader than COVID,” predicts Amy Kirby, a health scientist at the CDC who leads NWSS.

But there are challenges getting from promise to possible. So far, such sewage surveillance has been mostly a proof of concept, confirming data from other tracking systems. Experts are still determining how data from our poop can actually inform policy; that’s true even for COVID-19, now the poster child for this monitoring. And they face public officials wary of its value and questions over whether, now that COVID-19 health emergencies have ended, the pipeline of funding will be cut off.

This monitoring will hopefully become “one of the technologies that really evolves post-pandemic to be here to stay,” says Mariana Matus, cofounder of Biobot Analytics, a company based in Cambridge, Mass., that has tested sewage for the CDC and many other health agencies. But for that to happen, the technology needs continued buy-in from governments, research institutions and the public, Matus and other scientists say.