- New vaccination data from the CDC: The CDC has started publishing vaccination data reflecting how many Americans have received COVID-19, flu, and RSV shots in fall 2023. These numbers are estimates, based on the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, as the agency is no longer directly compiling COVID-19 vaccinations from state and local health agencies. (See this post from last month for more details.) According to the estimates, about 28% of American adults have received a 2023 flu shot, compared to 10% who have received a 2023 COVID-19 shot. The numbers reflect poor communication about and accessibility challenges with this year’s COVID-19 vaccines.

- FDA approves a rapid COVID-19 test: Following the end of the federal public health emergency this spring, the FDA has advised companies that produce COVID-19 tests to submit their products for full approval, transitioning out of the emergency use authorizations that these tests received earlier in the pandemic. The FDA has now fully approved an at-home COVID-19 test: Flowflex’s rapid, antigen test. This is the second at-home test to receive approval, following a molecular test a few months ago. The Floxflex test “correctly identified 89.8% of positive and 99.3% of negative samples” from people with COVID-like respiratory symptoms, according to a study that the FDA reviewed for this approval.

- WHO updates COVID-19 treatment guidance: This week, the World Health Organization updated its guidance on drugs and other treatment options for severe COVID-19 symptoms. A group of WHO experts has regularly reviewed the latest evidence and updated this guidance since fall 2020. The update includes guidelines on classifying COVID-19 patients based on their risk of potential hospitalization, recommendations for drugs such as nirmatrelvir and corticosteroids, and recommendations against other drugs such as invermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Clinicians can explore the guidance through an interactive tool that summarizes the expert group’s findings.

- Gargling with salt water to reduce symptoms: Speaking of COVID-19 treatments: gargling with salt water may help people with milder COVID-19 symptoms recover more quickly, according to a new study presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s annual conference. The researchers compared COVID-19 outcomes among people who did and did not use salt water for 14 days while sick; those who used the treatment had lower risks of hospitalization and reported shorter periods of symptoms. This study has not yet been peer-reviewed and more research will be needed, but it’s still helpful evidence to back up salt water as a potential treatment (something I’ve personally seen recommended anecdotally in the last couple of years).

- Allergies as potential Long COVID risk factors: Another study that caught my attention this week: researchers at the University of Magdeburg in Germany conducted a review of connections between allergies and Long COVID. The researchers compiled data from 13 past papers, including a total of about 10,000 study participants. Based on these studies, people who have asthma or rhinitis (i.e. runny nose, congestion, and similar symptoms, usually caused by seasonal allergies) are at higher risk for developing Long COVID after a COVID-19 case. The researchers note that this evidence is “very uncertain” and more investigation is needed; however, the study aligns with reports of people with Long COVID getting diagnosed with mast cell activation syndrome (or MCAS, an allergy-related condition).

- Dropping childhood vaccination rates: One more notable study, from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): vaccination rates for common childhood vaccines are declining among American kindergarteners, according to CDC research. CDC scientists reviewed data reflecting the childhood vaccinations that are required by 49 states and D.C. for the 2022-23 school year, and compared those numbers to past years. Overall, 93% of kindergarteners had completed their state-required vaccinations last school year, down from 95% in the 2019-20 school year, while vaccine exemptions increased to 3%. In 10 states, more than 5% of kindergarteners had exemptions to their required vaccines—signifying increased risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in schools, according to the CDC.

Tag: vaccine distribution

-

Sources and updates, November 12

-

How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?

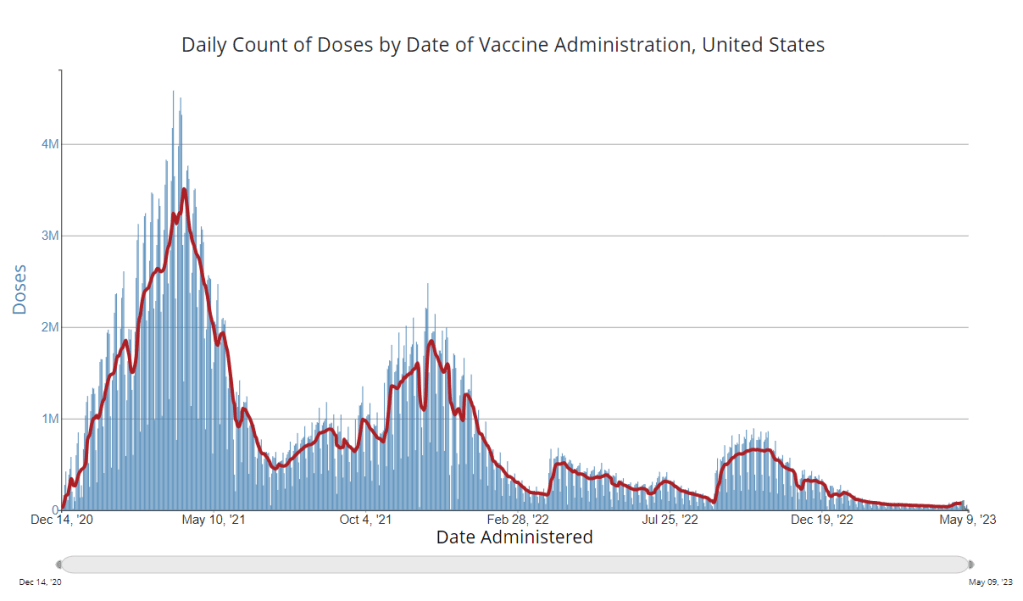

The CDC’s vaccination data pages all stopped updating in May 2023. How is the agency tracking our current round of shots? It’s now been a couple of weeks since updated COVID-19 vaccines became available in the U.S. At this point in prior COVID-19 vaccine rollouts, we would know a lot about who had received those vaccines: data would be available by state, for different age groups, and other demographic categories.

This time, though, the data are missing on a national scale. Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards.

But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations. In fact, last week, the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) told reporters that more than seven million Americans have received updated COVID-19 vaccines so far this fall.

HHS also said that about 14 million doses have been shipped to vaccination sites, primarily pharmacies. In addition, 710,000 vaccines for children have been ordered through a federal program that provides these shots.

Vaccine distribution numbers are slightly easier for the CDC and HHS to collect, as they can work directly with vaccine manufacturers. To understand how many people are getting the shots, though, is more challenging—requiring a mix of data from state and local agencies, surveys, and other surveillance mechanisms.

What changed with the PHE’s end:

Early in the pandemic, the CDC established data-sharing agreements with the health agencies that keep immunization records. This includes all states, territories, and a few large cities (such as New York City and Philadelphia) that have separate records systems from their states; you can see a full list of records systems here.

Through those agreements, the CDC collected vaccine administration numbers, standardized the data (as much as possible), and reported them on public dashboards. The CDC wasn’t able to collect as detailed demographic information as many health experts would’ve liked—for example, they never reported vaccinations by race and ethnicity below the national level. But the data were still useful for tracking who got vaccinated across the U.S.

These data-sharing agreements concluded with the end of the public health emergency (PHE) in May 2023. According to a CDC report published at that time, the CDC was able to extend agreements with some jurisdictions past the PHE’s end. Still, the report’s authors acknowledged that “future data might not be as complete” as during the emergency period. Even if 40 out of 50 states keep reporting, the remaining 10 represent data gaps.

Notably, the May report also claims that the CDC would continue to provide data on COVID-19 vaccination coverage on the CDC’s COVID-19 dashboard and a separate vaccination dashboard. But neither of those dashboards has been updated with any information from this fall’s vaccine campaign, as of this publication.

In addition to compiling data from state and local systems, the CDC has other mechanisms for tracking vaccinations. According to CBS News reporter Alexander Tin, CDC officials highlighted a couple during a briefing on October 4:

- The National Immunization Survey, a phone survey conducted by CDC officials to estimate national vaccination coverage based on a representative sample of Americans. This survey is currently the CDC’s method for tracking flu vaccinations.

- CDC’s Bridge Access and Vaccines for Children (VFC) programs, both of which buy vaccines to distribute to Americans who may not have health insurance or face other financial barriers to vaccination. The Bridge Access program was specifically set up for COVID-19 vaccines, while the VFC program covers other childhood vaccines.

- Contact with vaccine manufacturers and distributors, i.e. the pharmaceutical companies that make the vaccines and the pharmacies and healthcare organizations that give them out. These companies share data with the CDC, offering insights into how many vaccines have been distributed to different locations; though the data may not be comprehensive if not all distributors are included (i.e. just big pharmacy chains, not smaller, independent stores).

Other places to look for vaccination data:

Outside of the CDC, there are a few other places where you can look for vaccination data. Here are a couple that I’m monitoring:

- State and local public health agencies: Some agencies that track immunizations have their own dashboards, reporting on vaccinations in a specific state or locality. For example, New York City’s health department tracks COVID-19 vaccinations among city residents, although the agency hasn’t yet published data for this fall’s vaccines. I have a list of state vaccination dashboards here; this doesn’t currently represent data on the fall 2023 vaccines, but I aim to do that update in the coming weeks.

- Outside surveys, such as KFF’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Like the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, other health organizations conduct surveys to track vaccinations. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is one well-known project, which has been doing regular surveys on COVID-19 vaccine uptake since December 2020.

- Scientific reports answering specific vaccination questions: Public health researchers may use surveys, immunization records, or other data systems to study specific questions about vaccination, such as the impact that vaccination has on lowering a patient’s risk of severe disease. These studies are often published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and other journals.

If you have other questions about vaccination data—or want to share a data source I didn’t mention here—please reach out: email me or leave a comment below.

-

Did you have a hard time getting an updated COVID-19 vaccine? Tell us about it.

In the last week, my social media feeds have been full of stories about vaccine access issues. Even though the updated COVID-19 vaccines are supposed to be free—either covered by insurance plans or by a federal program—people keep getting bills. Or their vaccine appointments are canceled unexpectedly. Or they can’t get an appointment at all.

Some news outlets have covered these access challenges, but far more attention is needed. The new vaccines are the U.S. government’s only real strategy to curb a likely COVID-19 surge this winter, now that masks, testing, and other tools are far less available. It is absolutely crucial that as many people get vaccinated as possible, and any barriers to those vaccinations deserve front-page headlines.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch may not have the reach of an established national media outlet, but with the help of all of you readers, we can help draw more attention to this massive problem. If you have had a hard time getting an updated COVID-19 shot, please share your experience: you can use this Google form, email me, or reach out on social media (Twitter, Bluesky, Mastodon).

You can share your vaccination experience anonymously or attach your name, location, or other details, if you’d like. (There are no required fields on the Google form.) Next week, I’ll publish the responses in a public database on the CDD website. My hope is that this compilation can show how widespread these vaccine access issues are, and can serve as a resource for other journalists who might be interested in covering the problem.

Also, a PSA: if a pharmacy or doctor’s office tries to charge you for a COVID-19 vaccine, remind them that the vaccines are free. You can refer them to the CDC’s Bridge Access Program, which will pay for any vaccinations not covered by insurance.

-

FDA and CDC simplify COVID-19 vaccine guidance

This week, the FDA made some adjustments to the U.S.’s COVID-19 vaccine guidance in order to standardize all new mRNA shots to bivalent (or Omicron-specific) vaccines, and to allow adults at higher risk to receive additional boosters. The CDC’s vaccine advisory committee and Director Rochelle Walensky both endorsed these changes.

Here are the main updates you should know. For more details, I recommend reading Helen Branswell’s reporting in STAT News and/or Katelyn Jetelina’s coverage in Your Local Epidemiologist.

- Adults are now considered “up to date” on their COVID-19 vaccines if they have received at least one dose of a bivalent/Omicron-specific vaccine. These are the vaccines manufactured by Pfizer and Moderna that became available last fall.

- Any unvaccinated adult should receive one dose of a bivalent vaccine, rather than the former primary series (which was based on the original coronavirus strain). The prior vaccines will essentially go out of use in the U.S.

- Seniors (65 or older) and immunocompromised adults may receive an additional bivalent vaccine dose, starting at four months after their prior dose. Recent research has demonstrated that protection from these shots wanes over a couple of months, so there’s a good case for seeking out a new booster if you fall into one of these high-risk categories.

- Immunocompromised adults may receive more bivalent doses going forward, in consultation with their doctors. This guidance intends to provide more protection to people who are severely immunocompromised, such as those undergoing cancer treatment.

- A new version of the bivalent booster will likely be available in the fall, designed to protect against more recent coronavirus variants. We don’t know much about this yet, but prior FDA and CDC meetings have suggested it will roll out on a similar schedule to the annual flu shot.

These recommendations mostly apply to adults. While the FDA and CDC are also working on simplifying their guidance for children (to similarly prioritize vaccines aligned to current variants), that’s still a more complicated situation right now. See the YLE post for more details.

Another open question, at the moment, is what non-mRNA vaccines may be available, for people who may be allergic to those vaccines or who had severe reactions to earlier doses. Novavax is reportedly working on a bivalent/Omicron-specific option, which people might be able to get this fall. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is no longer widely used at all.

It makes sense for the FDA and CDC to shift towards bivalent vaccines. Numerous studies have demonstrated that these vaccines perform better against Omicron variants, and this move simplifies the immunization process for everyone involved (doctors, pharmacies, patients, etc.).

However, this shift reveals how poorly the bivalent booster rollout has gone in the U.S. so far. Only 17% of the population has received one, compared to 81% who’s received at least one dose overall, according to the CDC. Even among seniors, only 42% have received a bivalent booster. It would be a massive task for the country to move towards “up-to-date” coverage among all adults.

And the federal government doesn’t appear to be pushing for this in any meaningful way. I’ve already seen several reports on social media of people trying to get an additional booster, and failing—whether because of an insurance issue or because pharmacies have simply stopped offering the shots. This process will only get more challenging when the federal public health emergency ends next month. While the Biden administration has announced funding to cover vaccines for uninsured Americans, that’s just one hurdle among a growing number.

More vaccine coverage

-

Sources and updates, December 11

- 2022 America’s Health Rankings released: This week, the United Health Foundation released its 2022 edition of America’s Health Rankings, a comprehensive report providing data for more than 80 different health metrics at national and state levels. The 2022 report includes new metrics tailored to show COVID-related disparities; for example, Black and Hispanic Americans had higher rates of losing friends and family members to COVID-19 compared to other groups. I’ve used data from past iterations of this report in stories before, and I’m looking forward to digging into the 2022 edition.

- FDA authorizes bivalent boosters for young kids: This week, the FDA revised the emergency use authorizations (EUAs) of both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s updated, Omicron-specific booster shots to include children between six months and five years old. Kids who previously got two shots of Moderna’s vaccine for this age group can receive a bivalent booster two months later, while kids who got two shots of Pfizer’s vaccine can receive a bivalent booster as their third dose. (Remember, Pfizer’s vaccine for this age group includes three doses.) The updated EUAs will help protect young children from Omicron infection, though uptake will likely be low.

- CDC updates breakthrough case data: Speaking of the updated boosters: the CDC recently added data on these shots to its analysis of COVID-19 cases and deaths by vaccination status. In September, people who had received a bivalent, Omicron-specific boosters had a 15 times lower risk of dying from COVID-19 compared to unvaccinated people; and in October, bivalent-boosted people had a three times lower risk of testing positive compared to the unvaccinated. The CDC will update these data on a monthly basis.

- Director Walensky discusses authority challenges: One bit of coverage from the Milken Future of Health Summit that caught my attention: CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky talked about the agency’s limitations in collecting data from states, reports Rachel Cohrs at STAT News. Walensky specifically highlighted the challenges that the CDC might face in collecting data when the public health emergency for COVID-19 ends, something I’ve previously covered in this publication.

- Boston establishes neighborhood-level wastewater testing: Finally, one bit of wastewater surveillance news: the city of Boston is setting up 11 new sites to test wastewater, giving local public health officials more granular information about how COVID-19 is spreading in the region. The new initiative is a partnership with Biobot Analytics, the same wastewater testing company that has long worked with Boston, the CDC, and public health institutions across the country. (Boston was one of the first cities to start doing this testing.) Also, speaking of Biobot: the company just added a nice chart of coronavirus variants in U.S. wastewater over time to its dashboard.

-

Sources and updates, October 30

- More detailed bivalent booster data: As of this week, the CDC is reporting some demographic data for the bivalent, Omicron-specific booster shots. The new data suggest that these boosters have had higher uptake among seniors, with about 11 million people over age 65 receiving a shot (compared to just 60,000 in the 5 to 11 age group). White and Asian Americans have higher booster rates than Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans, suggesting that the new doses are following a similar equity pattern to what we’ve seen with prior vaccines.

- COVID-19 mortality by occupation: A new report by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System provides a rare area of data we don’t usually get in the U.S.: occupational data. CDC researchers used mortality data from 46 states and New York City to examine risk of death by occupation. People working in protective services, accommodation and food services, and other essential jobs that couldn’t be done remotely had the highest death rates—confirming what many public health experts have suspected throughout the pandemic.

- Life expectancy changes during the pandemic: A new study published in Nature, by researchers at the University of Oxford and other European institutions, estimated how life expectancy changed in 29 countries since the start of the pandemic. After a universal life expectancy decline in 2020, the researchers found, some western European countries “bounced back” in 2021 while the U.S. and eastern European countries did not. The results show the impacts of lower vaccination uptake in the U.S., particularly among younger adults.

- Disparities in Paxlovid prescriptions: Another CDC study that caught my attention this week was this analysis in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), describing racial and ethnic disparities in prescriptions of Paxlovid—the antiviral COVID-19 treatment which reduces risk of severe symptoms. Between April and July 2022, the researchers found, the share of COVID-19 patients over age 20 who received a Paxlovid prescription was 36% lower among Black patients than among White patients, and 30% lower among Hispanic patients. More work is needed to make Paxlovid availability more equitable.

- New estimates of Long COVID prevalence: One more notable paper published this week: researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard, and collaborators conducted an online survey of about 16,000 U.S. adults who tested positive for COVID-19 in the last two months. Of those survey respondents, 15% reported current symptoms of Long COVID. The survey found that older adults and women were more likely to report Long COVID, while those who were fully vaccinated prior to infection had a somewhat lower risk of long-term symptoms. All of these findings are in line with results from other studies, but it’s helpful to see continued validation of these known trends.

-

Sources and updates, October 23

- Genomic surveillance from international travelers: A new CDC dashboard page provides data from the agency’s program sequencing COVID-19 test samples from people arriving in the U.S. on international flights, aiming to identify and track new variants. This program—a partnership between the agency, Ginkgo Bioworks, and XpresSpa Group—started during the Delta wave in 2021 with flights from India, but has since expanded to include over 1,000 volunteers a week at four major airports. The CDC’s new page reports test positivity for travelers’ samples and variants detected through sequencing.

- Implications of commercializing COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, tests: Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation analyzed how the federal government’s decreasing support for key COVID-19 products (vaccines, treatments, and tests) could impact Americans’ access. The government’s supply of these products has been depleted through 2022, and researchers anticipate the national Public Health Emergency will end in early 2023. As a result, Americans will soon likely need to rely on commercial products, leading to major challenges for low-income and uninsured people. (I wrote more about data implications of the PHE ending here.)

- Disparities in flu hospitalizations and vaccinations: Much COVID-19 coverage, including in this publication, has focused on inequitable vaccine uptake. In early 2021, more white Americans were getting vaccinated than minority groups, potentially contributing to higher rates of severe disease in those groups through the second year of the pandemic. A new CDC study in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) finds that a similar trend has occurred for flu over the last ten years: Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans had lower flu vaccine coverage than white Americans from 2009-10 through 2021-22 seasons, and the same groups had higher flu hospitalization rates. The study suggests equitable vaccination is a problem that goes beyond the pandemic.

- Vaccine coverage among healthcare workers: Another CDC MMWR study that caught my attention this week provides results from a survey of healthcare workers, conducted in spring 2022. Among about 3,700 workers who responded to the survey, about four in five reported receiving a flu shot and two in three reported receiving a COVID-19 booster (during the 2021-22 flu season). Workers with vaccine mandates at their jobs had higher coverage than these averages, while long-term care workers had lower coverage. The results indicate more effort is needed to protect healthcare workers and their patients.

- HospitalFinances.org is revamped, newly available: In 2018, the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) first launched HospitalFinances.org, a database of financial information on nonprofit hospitals pulling from 990 tax forms. The site has been offline for the past year due to a hosting issue, but is now back thanks to researchers at the University of Missouri (which hosts AHCJ). While this resource isn’t specifically COVID-related, it could be useful to reporters investigating hospitals in their areas.

-

COVID source shout-out: Bloomberg’s vaccine tracker

Last week, the team behind Bloomberg’s COVID-19 vaccine tracker announced that the dashboard will stop updating on October 5.

Drew Armstrong, senior health care editor and leader of the tracking effort, provided the motivations for this decision in an update post. New rounds of booster shots around the world, including bivalent shots in some countries, have made it harder to track and present data: “There are more categories of data to collect and fewer simple comparisons among the more than 100 countries we’ve been tracking,” Armstrong wrote.

Armstrong also explained that the vaccine tracker has been a huge lift for Bloomberg, and the company is only able to put so many resources into a dashboard that really should be provided by government or academic institutions. (The COVID Tracking Project’s leaders said something similar when that project stopped data collection in spring 2021.)

While I’m sad to see this tracker go, I understand the decision and remain very grateful for all the work that’s gone into it since vaccination campaigns started in winter 2020. Congratulations to all of the Bloomberg journalists who contributed to this valuable resource!

-

The U.S. needs to step up its booster shot campaign

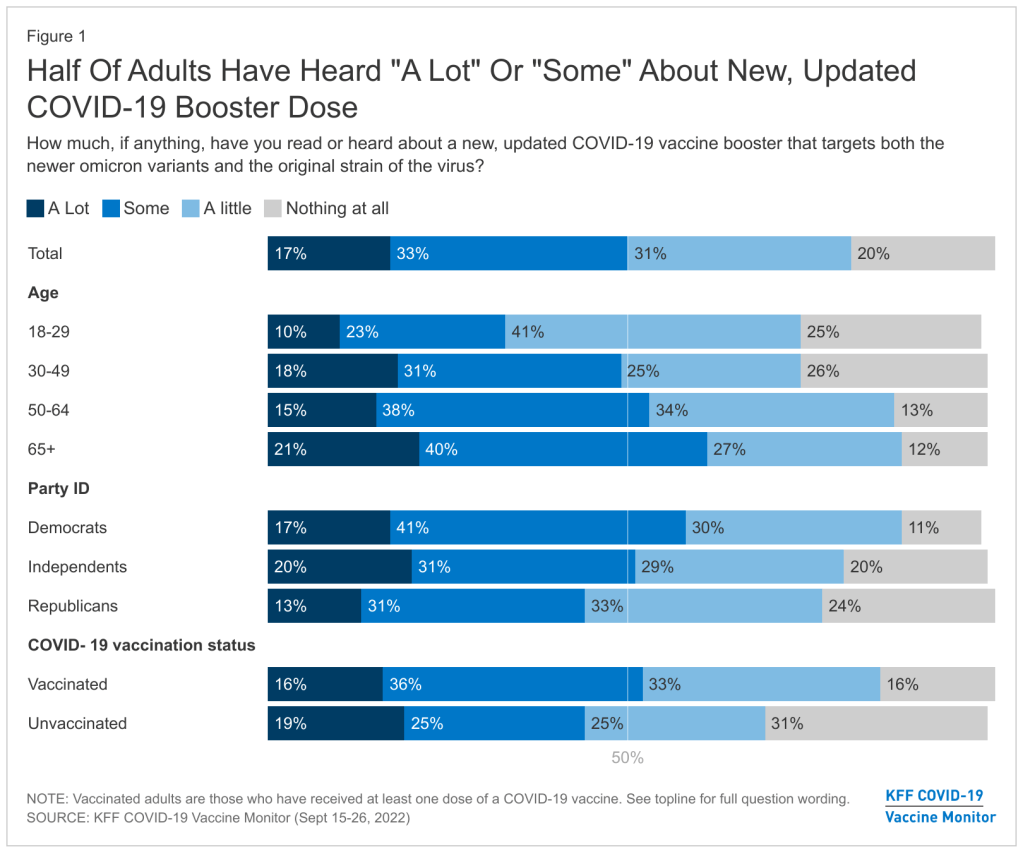

About half of U.S. adults haven’t heard much about the updated COVID-19 booster shots, according to a recent survey done by the Kaiser Family Foundation. New, Omicron-specific booster shots are publicly available for all American adults who’ve been previously vaccinated. This is the first time our shots actually match the dominant coronavirus variant (BA.5), and possibly the last time that the shots will be covered for free by the federal government.

So… why does it feel like almost nobody knows about them? Since the CDC and FDA authorized these shots, I’ve had multiple conversations with friends and acquaintances who had no idea they were eligible for a new booster. My own booster happened in a small, cramped room of a public hospital—a far cry from the mass vaccination sites that New York City has offered in past campaigns.

This week, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) provided some data to back up such anecdotal evidence. According to the September iteration of KFF’s Vaccine Monitor survey, about half of U.S. adults have heard only “a little” or “nothing at all” about the new boosters. That includes more than half of adults who have been previously vaccinated.

Moreover, the KFF survey found that 40% of previously vaccinated adults (who received the full primary series) are “not sure” if the updated booster is recommended for them. Another 11% said the new booster is not recommended for them—which is not true! The CDC has recommended these boosters for everyone who previously got vaccinated.

Booster eligibility knowledge is even lower in certain demographics, KFF found. That includes: 55% of previously vaccinated Black adults and 57% of Hispanic adults don’t know that they’re eligible for boosters. Same thing for 57% of vaccinated adults with less than a college education and 58% of those living in rural areas.

As of September 28, only 7.6 million Americans have received an updated booster shot, the CDC reports. Overall, the CDC reports that about 7.6 million Americans have received an updated booster shot as of September 28, including 4.9 million who received a Pfizer shot and 2.7 million who received a Moderna shot. This represents less than 4% of all fully vaccinated adults who are eligible for the new boosters. And we don’t have demographic data yet, but I expect the patterns will fall among similar lines to what KFF’s survey found.

“Clear and consistent messaging accompanied by strategies to deliver boosters is needed to narrow these gaps,” said public health expert Anne Sosin, sharing the KFF findings on Twitter. We need big, public campaigns for the new boosters in line with what we got for the original vaccines in 2021—or else the new shots won’t be very helpful in an inevitable fall/winter surge.

More vaccine data

-

Sources and updates, September 11

- White House plans for annual boosters: This week, Biden administration officials announced a plan for one COVID-19 shot each year, on a similar timeline to the flu shots distributed every fall. In this plan, this fall’s Omicron-specific boosters are the first iteration of annual boosters. Some scientists are skeptical about the plan, given that (as I discussed last week) we have very little data on how well the new boosters work. It could be preemptive to say just one shot each year will be enough, and the federal government should also be investing in next-generation vaccines that might better prevent infection and transmission.

- Urgency of Equity Toolkit: The People’s CDC, a health advocacy organization aiming to fill gaps in COVID-19 guidance left by the official CDC, has published a toolkit focused on school safety for the fall. The presentation walks readers through why public health measures are still needed in K-12 schools and potential layers of protection, such as improved ventilation, surveillance testing, and improving pediatric vaccination rates.

- Parents and caregivers lost to COVID-19: Speaking of protecting children, a new study published in JAMA Pediatrics this week estimates how many children have lost parents or caregivers during the pandemic. The researchers (an international group including experts at the World Health Organization, World Health Organization, and others) produced their estimates based on global excess mortality data—going beyond deaths officially reported as COVID-19. In total, the study estimates about 10.5 million lost parents or caregivers and 7.5 million became orphans worldwide.

- True virus prevalence during the BA.5 surge: I’ve previously cited the work of Denis Nash and his team at the City University of New York; they utilized a population survey to estimate how many New Yorkers actually got COVID-19 during the city’s spring surge. This week, the team shared a new study that uses the same approach for the whole country. While their sample size was fairly small (about 3,000 people) and the study has yet to be peer-reviewed, its findings are striking: about 17% of U.S. adults surveyed were infected by the coronavirus during a two-week period from late June to early July, around the peak of the BA.5 surge.

- New independent effort to study Long COVID: This week, a group of researchers, clinicians, and patients announced the Long Covid Research Initiative, a new collaborative effort to study the condition and identify potential treatments. The group has raised $15 million in private funding and aims to move more quickly than public or academic efforts that have been bogged down in bureaucracy (among other challenges). I’m excited to see what this new group finds.