- New vaccination data from the CDC: The CDC has started publishing vaccination data reflecting how many Americans have received COVID-19, flu, and RSV shots in fall 2023. These numbers are estimates, based on the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, as the agency is no longer directly compiling COVID-19 vaccinations from state and local health agencies. (See this post from last month for more details.) According to the estimates, about 28% of American adults have received a 2023 flu shot, compared to 10% who have received a 2023 COVID-19 shot. The numbers reflect poor communication about and accessibility challenges with this year’s COVID-19 vaccines.

- FDA approves a rapid COVID-19 test: Following the end of the federal public health emergency this spring, the FDA has advised companies that produce COVID-19 tests to submit their products for full approval, transitioning out of the emergency use authorizations that these tests received earlier in the pandemic. The FDA has now fully approved an at-home COVID-19 test: Flowflex’s rapid, antigen test. This is the second at-home test to receive approval, following a molecular test a few months ago. The Floxflex test “correctly identified 89.8% of positive and 99.3% of negative samples” from people with COVID-like respiratory symptoms, according to a study that the FDA reviewed for this approval.

- WHO updates COVID-19 treatment guidance: This week, the World Health Organization updated its guidance on drugs and other treatment options for severe COVID-19 symptoms. A group of WHO experts has regularly reviewed the latest evidence and updated this guidance since fall 2020. The update includes guidelines on classifying COVID-19 patients based on their risk of potential hospitalization, recommendations for drugs such as nirmatrelvir and corticosteroids, and recommendations against other drugs such as invermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Clinicians can explore the guidance through an interactive tool that summarizes the expert group’s findings.

- Gargling with salt water to reduce symptoms: Speaking of COVID-19 treatments: gargling with salt water may help people with milder COVID-19 symptoms recover more quickly, according to a new study presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s annual conference. The researchers compared COVID-19 outcomes among people who did and did not use salt water for 14 days while sick; those who used the treatment had lower risks of hospitalization and reported shorter periods of symptoms. This study has not yet been peer-reviewed and more research will be needed, but it’s still helpful evidence to back up salt water as a potential treatment (something I’ve personally seen recommended anecdotally in the last couple of years).

- Allergies as potential Long COVID risk factors: Another study that caught my attention this week: researchers at the University of Magdeburg in Germany conducted a review of connections between allergies and Long COVID. The researchers compiled data from 13 past papers, including a total of about 10,000 study participants. Based on these studies, people who have asthma or rhinitis (i.e. runny nose, congestion, and similar symptoms, usually caused by seasonal allergies) are at higher risk for developing Long COVID after a COVID-19 case. The researchers note that this evidence is “very uncertain” and more investigation is needed; however, the study aligns with reports of people with Long COVID getting diagnosed with mast cell activation syndrome (or MCAS, an allergy-related condition).

- Dropping childhood vaccination rates: One more notable study, from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): vaccination rates for common childhood vaccines are declining among American kindergarteners, according to CDC research. CDC scientists reviewed data reflecting the childhood vaccinations that are required by 49 states and D.C. for the 2022-23 school year, and compared those numbers to past years. Overall, 93% of kindergarteners had completed their state-required vaccinations last school year, down from 95% in the 2019-20 school year, while vaccine exemptions increased to 3%. In 10 states, more than 5% of kindergarteners had exemptions to their required vaccines—signifying increased risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in schools, according to the CDC.

Tag: vaccine communication

-

Sources and updates, November 12

-

Sources and updates, October 8

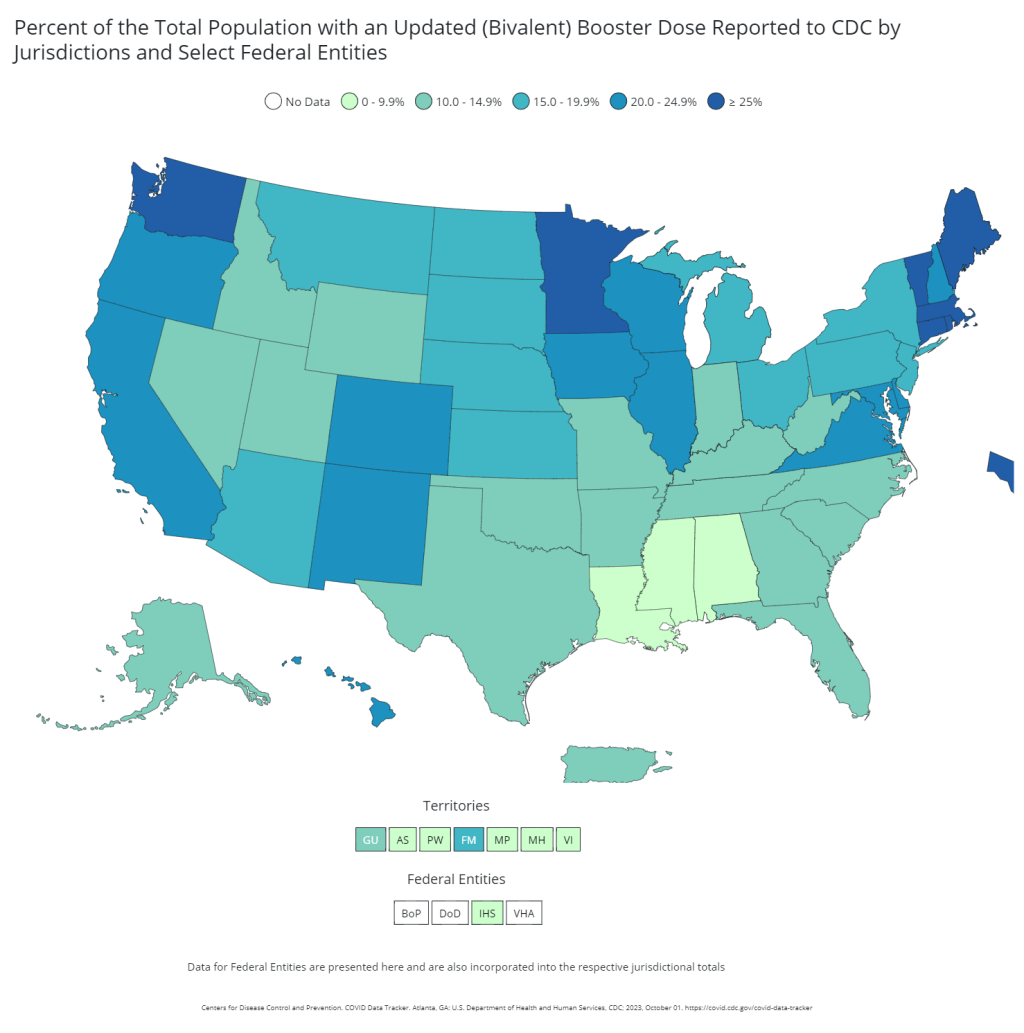

- Vaccination disparities in long-term care facilities: A new study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report shares vaccination patterns from about 1,800 nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care facilities across the U.S., focusing on the bivalent booster (or, last fall’s vaccine). The CDC researchers found significant disparities in these vaccinations: vaccine coverage was lowest among Black and Hispanic residents compared to other demographics, and was lowest in the South and Southeast compared to other regions. Future vaccination campaigns need to make it easy for these groups to get their shots, the authors suggest; but based on how the 2023 rollout has gone so far, this trend seems likely to continue.

- Reasons for poor bivalent booster uptake: Speaking of last fall’s boosters, a study from researchers at the University of Arizona suggests reasons why people didn’t get the shots last year. Researchers surveyed about 2,200 Arizona residents who had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Among the survey respondents who didn’t get last year’s booster, the most common reason for not doing so was a belief that a prior infection made the shot unnecessary (40%), concerns about vaccine side effects (32%), believing the booster wouldn’t provide additional protection over prior shots (29%), and safety concerns (23%). As with the study above, this paper shows weaknesses in the U.S.’s recent vaccine promotion strategies.

- At-home tests are useful but far from perfect: Researchers at Nagoya University and the University of Oxford used mathematical models to study how different safety measures impact chances of COVID-19 outbreaks. The researchers developed models based on contact tracing data reflecting how Omicron spreads through groups. Rapid, at-home, antigen tests are a useful but imperfect method for reducing outbreak risk, the study found, with daily testing reducing the risk of a school or workplace outbreak by 45% compared to a scenario in which new cases are identified by symptoms only. “In high-contact settings, or when a new variant emerges, mitigations other than antigen tests will be necessary,” one of the scientists said in a statement.

- Long-term symptoms from non-COVID infections: The prevalence of Long COVID has led many scientists to develop new interest in chronic conditions that may arise after other common infections, such as the flu and other respiratory viruses. One recent study from Queen Mary University of London identifies a potential pattern, using data from COVIDENCE UK, a long-term study tracking about 20,000 people through monthly surveys. Researchers compared symptoms between people who had a COVID-19 diagnosis and those with other respiratory infections, looking at the month following infection. They found similar risks of health issues in the one-month timeframe for both groups, though specific symptoms (loss of taste and smell, dizziness) were more specific to Long COVID. Of course, some people in the “non-COVID” group could have had COVID-19 without a positive test; still, the data indicate more, longer-term research is needed.

- Autoimmune disorders following COVID-19: In another Long COVID-related paper, researchers at Yonsei University and St. Vincent’s Hospital in South Korea found that patients had increased risks of autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders following COVID-19 cases. The study used patient records from South Korea’s national public health system, comparing about 354,000 people who had COVID-19 diagnoses to 6.1 million controls. COVID-19 patients had a significant risk of new autoimmune issues within several months after infection; new diagnoses included alopecia (or hair loss), Crohn’s disease (inflammatory bowel issues), sarcoidosis (overactive immune system), and more. These conditions should be considered by doctors evaluating potential Long COVID patients, the researchers wrote in their paper.

- New climate vulnerability index: This last item isn’t directly COVID-19 related, but may be useful in evaluating community risks for public health threats. The Environmental Defense Fund, Texas A&M University, and other partners have launched the U.S. Climate Vulnerability Index, a database providing Census tract-level information about how our changing climate will impact different communities. Communities are ranked from low to high climate vulnerability, with detailed data available on sociodemographic characteristics as well as potential extreme weather events and health trends.

-

COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.

Last year, just 17% of the U.S. population received a bivalent booster. Will this year’s uptake be better? Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.

I’ve published the full responses in the table below. Here are a few common themes that I saw in these stories:

- Pharmacies aren’t receiving enough vaccines. Several readers shared that their pharmacies had inadequate vaccine supply to accommodate all the people who made vaccination appointments, or who wanted appointments. Vaccine supply may also be unpredictable—a pharmacy may think they’re getting more shots, but in fact not receive them—leading to appointment cancellations.

- Insurance providers weren’t prepared for this vaccine rollout. Despite months of advance notice that a fall COVID-19 vaccine was coming, many insurance companies apparently failed to prepare billing codes or other system updates that would allow them to cover the shots. A couple of people who shared insurance issue stories are on Medicare—representing a population (i.e. seniors) who should be at the front of the vaccine line.

- Very limited, confusing vaccine availability for young kids. Several readers shared that they were able to get vaccinated, but their children under 12 have not received a vaccine yet. While the FDA and CDC have authorized this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines for all Americans ages six months and older, younger children require a different vaccine formulation from adults. And this formulation appears either entirely unavailable or very difficult to access, depending on where you live.

- People living in less dense areas may need to travel. A few readers shared that, as they searched for vaccine appointments in their areas, the closest pharmacies with doses available were miles away—over 10 miles, in one case. This is a significant barrier for people fitting vaccine appointments into their work schedules.

- Information may be inconsistent. Vaccine availability listed in one place (such as a pharmacy chain’s website or the federal vaccines.gov website) may be inaccurate in another. Some readers shared that they spent extra time on the phone with pharmacies or health providers to get accurate information—another barrier.

- Pharmacies don’t have enough staff for this. Even readers who were able to receive COVID-19 vaccines often had to wait a long time at their pharmacies. Several shared that their pharmacies appeared to be understaffed, dealing with the COVID-19 shots along with routine prescriptions and other duties. The days of mass vaccination sites, efficiently run by public health departments, are long over.

- Kaiser Permanente members face delays. One company that appears to be causing outsized problems is Kaiser Permanente, one of the biggest insurers and health providers on the West Coast. Several readers shared that Kaiser was not providing new COVID-19 vaccines until early October, and would not cover the shots if their members went to another location. That’s a big delay, and it may be further impacted by a coming strike at the company.

- These vaccines are expensive. If you decide to pay for a COVID-19 shot out-of-pocket (as some readers did), it costs almost $200. Even the federal government is paying about triple the cost of last year’s COVID-19 vaccines per shot, for the doses it is covering, STAT News reports. The U.S. may have received a “bad deal” here, STAT suggests, considering all of the federal funding that’s supported vaccine research and development.

As I wrote last week, some news outlets have covered these challenges, but this issue really deserves more attention. The updated COVID-19 vaccines are basically the U.S. government’s only strategy to curb a surge this winter, and they should be easily, universally accessible. Instead, many people eager to get vaccinated are going through multiple rounds of appointments, phone calls, pharmacy lines, and more.

For every one of these readers who has persisted in getting their shot, there are likely many other people who tried once and then gave up. And those people who don’t receive the vaccine will be at higher risk of severe illness, death, and long-term symptoms from COVID-19 this fall and winter. This is a public health failure, plain and simple.

And it’s important to emphasize that this failure is not surprising. Many health commentators predicted that these challenges would arise as the federal public health emergency ended and COVID-19 tools transitioned from government-funded to covered-by-insurance. For more context on why this is happening, I recommend the Death Panel podcast’s latest episode, “Scenes from the Class Struggle at CVS.”

If you’re a reporter who would like to connect with one of the COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers who shared a story, please email me at betsy@coviddatadispatch.com. Most of the people in the database below shared an email or other contact info.

[table id=10 responsive=collapse responsive_breakpoint=all /] -

COVID source call-out: When will we get fall boosters?

The CDC expects that our next round of COVID-19 booster shots will be available in early fall, likely late September or early October. But this limited information has been distributed not through formal reports or press releases—rather, through the new CDC director’s media appearances.

These booster shots will be targeted to Omicron XBB.1.5, one of the most recently-circulating subvariants. It’ll be an important immunity upgrade, especially for seniors and other higher-risk people, as the last round of updated vaccines came almost a year ago. Plus, these new boosters are basically the federal government’s one initiative to combat COVID-19 as we head into another inevitable fall and winter of respiratory illness.

Considering the shots’ importance, we have surprisingly little information about when they’ll be available or how they will be distributed. During one media appearance (on NPR’s All Things Considered in early August), CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen said that the boosters would be available “probably in the early October time frame.” Then, a week later (on former federal official Andy Slavitt’s podcast), she said boosters would come “by the third or fourth week of September.”

In both interviews, Cohen shared few details beyond this vague timeline. I would love to see more details from the federal government about their plans—for producing the shots, and also for distributing them in our post-federal emergency landscape. It also seems unclear how the CDC and other agencies will promote the boosters, considering how most officials are now pretending COVID-19 is no longer a concern. (Case in point: Cohen’s many mask-less appearances since she started as CDC director.)

-

Sources and updates, January 22

- New CDC dashboards track respiratory illness hospitalizations: This week, the CDC released two new dashboards that combine COVID-19 data with data on other respiratory illnesses. First, the RESP-NET dashboard summarizes information from population-based hospital surveillance systems in 13 states for COVID-19, the flu, and RSV; it includes overall trends and demographic data. Second, the National Emergency Department Visits dashboard provides data on emergency department visits for COVID-19, the flu, RSV, and all three diseases combined; this dashboard includes data from all 50 states, though not all hospitals are covered.

- Early results from NIH at-home test self-reporting: Last week, ABC News shared early results from MakeMyTestCount.org, an online tool run by the National Institutes of Health allowing Americans to self-report their rapid, at-home test results. Between the site’s launch in late November and early January, “24,000 people have reported a test result to the site,” according to ABC. (While the article says “people have reported,” I think this number actually represents the number of test results reported, given that the website doesn’t track when one person submits multiple test results over time.) The majority of results reported are positive and women are more likely to self-report than men, per ABC. It’s unclear how useful these early data may be for any analysis, but I’m glad to see some numbers becoming public.

- New preprint updates county-level excess death estimates: A new preprint from Boston University demographer Andrew Stokes and colleagues, posted this week on medRxiv, shares updated estimates on excess deaths and COVID-19 deaths by U.S. county. According to the analysis, about 270,000 excess deaths were not officially attributed to COVID-19 during the first two years of the pandemic, representing 24% of all excess deaths during that time. And the analysis reveals regional patterns: for example, in the South and in rural patterns, excess deaths were less likely to be officially attributed to COVID-19. For more context on these data, see MuckRock’s Uncounted project (which is a collaboration with Stokes and his team).

- Factors contributing to low bivalent booster uptake: Another notable paper from this week: results from a survey of Americans who were previously vaccinated about their reasons for receiving (or not receiving) a bivalent, Omicron-specific booster this fall, conducted by researchers at Duke University, Georgia Institute of Technology, and others. Among about 700 people who didn’t get the booster, their most common reasons were a lack of awareness that the respondent was eligible for this vaccine, a lack of awareness that the bivalent vaccine was widely available, and a perception that the respondent already had sufficient protection against COVID-19. This survey shows how governments at every level have failed to advertise the bivalent boosters, likely to dire results.

- More wastewater surveillance on airplanes: And one more notable paper: researchers at Bangor University tested wastewater from three international major airports in the U.K., including samples from airplanes and airport terminals. About 93% of the samples from airplanes were positive for SARS-CoV-2, while among the airport terminal samples, 100% at two airports were positive and 85% at the third airport were positive. Similar to the study from Malaysia I shared last week, this paper suggests that there’s a lot of COVID-19 going around on air travel—to put it mildly. The paper also adds more evidence that airplane/airport wastewater can be a useful source for future COVID-19 surveillance.

- Nursing home infections ran rampant early in the pandemic: A new report from the Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General examines how much COVID-19 spread through nursing homes in 2020. The report’s authors used Medicare data from about 15,000 nursing homes nationwide, identifying those with “extremely high infection rates” in spring and fall 2020. In more than 1,300 of these facilities, 75% or more of the Medicare patients had COVID-19 during these surges; the same facilities had way-above-average mortality rates. “These findings make clear that nursing homes in this country were not prepared for the sweeping health emergency that COVID-19 created,” the authors write in the report’s summary.

-

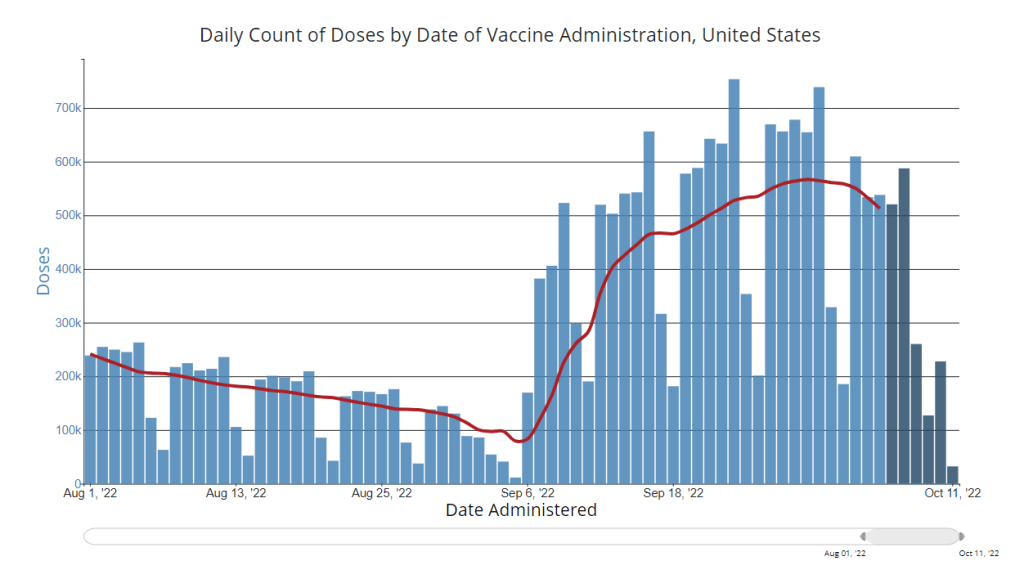

National numbers, October 16

After a small uptick in vaccinations thanks to the new boosters, vaccinations are already slowing again. Chart via the CDC, data as of October 12. In the past week (October 8 through 14), the U.S. reported about 270,000 new COVID-19 cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 39,000 new cases each day

- 83 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 12% fewer new cases than last week (October 1-7)

In the past week, the U.S. also reported about 23,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals. This amounts to:

- An average of 3,300 new admissions each day

- 7.0 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 4% fewer new admissions than last week

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 2,300 new COVID-19 deaths (330 per day)

- 12% of new cases are caused by Omicron BA.4.6; 11% by BQ.1 and BQ.1.1; 5% by BF.7; 3% by BA.2.75 and BA.2.75.2 (as of October 15)

- An average of 400,000 vaccinations per day

While official case numbers remain low compared to past fall seasons—both national cases and hospital admissions dropped again this week—signals of a coming fall surge are accumulating from wastewater and local data.

According to Biobot’s dashboard, the coronavirus continues to spread in the Northeast at higher levels than the rest of the country with a new uptick this week. In places like Franklin County, Massachusetts, Fairfield County, Connecticut, and Middlesex County, New Jersey, coronavirus levels are higher now than they have been at any point in the last six months.

Similar patterns are starting to show up in clinical data: Northeast states including Vermont, Maine, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey reported increased COVID-19 patients this past week, according to the October 13 Community Profile Report.

Along with colder weather and behavior patterns, new Omicron lineages could contribute to the increased transmission—if they aren’t contributing already. BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, two sublineages from BA.5, are now causing about 11% of new cases nationwide, according to the CDC’s most recent variant prevalence update. In the northeast, their prevalence is approaching to 20%. (More on the new subvariants in the next post.)

As many of the sublineages now circulating are descended from BA.5 or BA.4, the bivalent booster shots designed to protect against these variants should still help protect against newer strains. In fact, the FDA and CDC recently expanded eligibility for these new shots to younger age groups, going down to kids ages five to eleven.

But uptake of the new boosters remains low—in part because public communication has been so limited, many Americans don’t know they qualify for these shots. Only 15 million people have received the boosters as of October 12, a tiny fraction of the eligible population.

-

The U.S. needs to step up its booster shot campaign

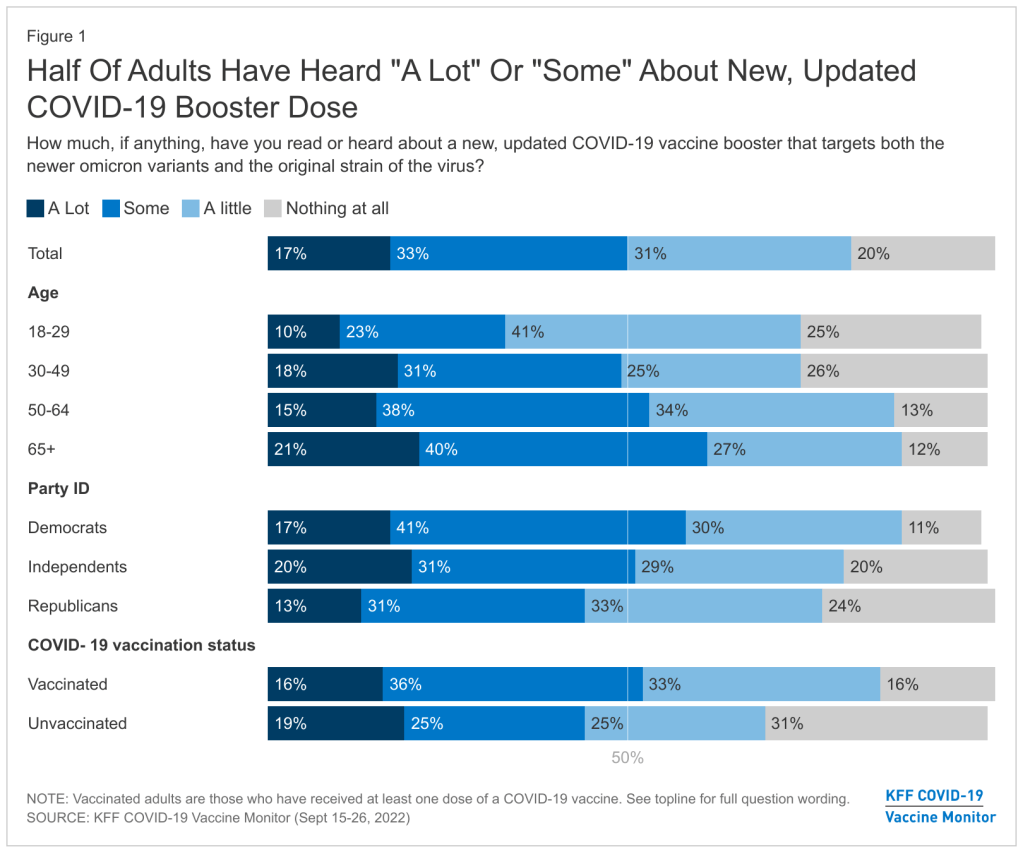

About half of U.S. adults haven’t heard much about the updated COVID-19 booster shots, according to a recent survey done by the Kaiser Family Foundation. New, Omicron-specific booster shots are publicly available for all American adults who’ve been previously vaccinated. This is the first time our shots actually match the dominant coronavirus variant (BA.5), and possibly the last time that the shots will be covered for free by the federal government.

So… why does it feel like almost nobody knows about them? Since the CDC and FDA authorized these shots, I’ve had multiple conversations with friends and acquaintances who had no idea they were eligible for a new booster. My own booster happened in a small, cramped room of a public hospital—a far cry from the mass vaccination sites that New York City has offered in past campaigns.

This week, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) provided some data to back up such anecdotal evidence. According to the September iteration of KFF’s Vaccine Monitor survey, about half of U.S. adults have heard only “a little” or “nothing at all” about the new boosters. That includes more than half of adults who have been previously vaccinated.

Moreover, the KFF survey found that 40% of previously vaccinated adults (who received the full primary series) are “not sure” if the updated booster is recommended for them. Another 11% said the new booster is not recommended for them—which is not true! The CDC has recommended these boosters for everyone who previously got vaccinated.

Booster eligibility knowledge is even lower in certain demographics, KFF found. That includes: 55% of previously vaccinated Black adults and 57% of Hispanic adults don’t know that they’re eligible for boosters. Same thing for 57% of vaccinated adults with less than a college education and 58% of those living in rural areas.

As of September 28, only 7.6 million Americans have received an updated booster shot, the CDC reports. Overall, the CDC reports that about 7.6 million Americans have received an updated booster shot as of September 28, including 4.9 million who received a Pfizer shot and 2.7 million who received a Moderna shot. This represents less than 4% of all fully vaccinated adults who are eligible for the new boosters. And we don’t have demographic data yet, but I expect the patterns will fall among similar lines to what KFF’s survey found.

“Clear and consistent messaging accompanied by strategies to deliver boosters is needed to narrow these gaps,” said public health expert Anne Sosin, sharing the KFF findings on Twitter. We need big, public campaigns for the new boosters in line with what we got for the original vaccines in 2021—or else the new shots won’t be very helpful in an inevitable fall/winter surge.

More vaccine data

-

COVID-19 risk factors that should lead to Omicron booster priority

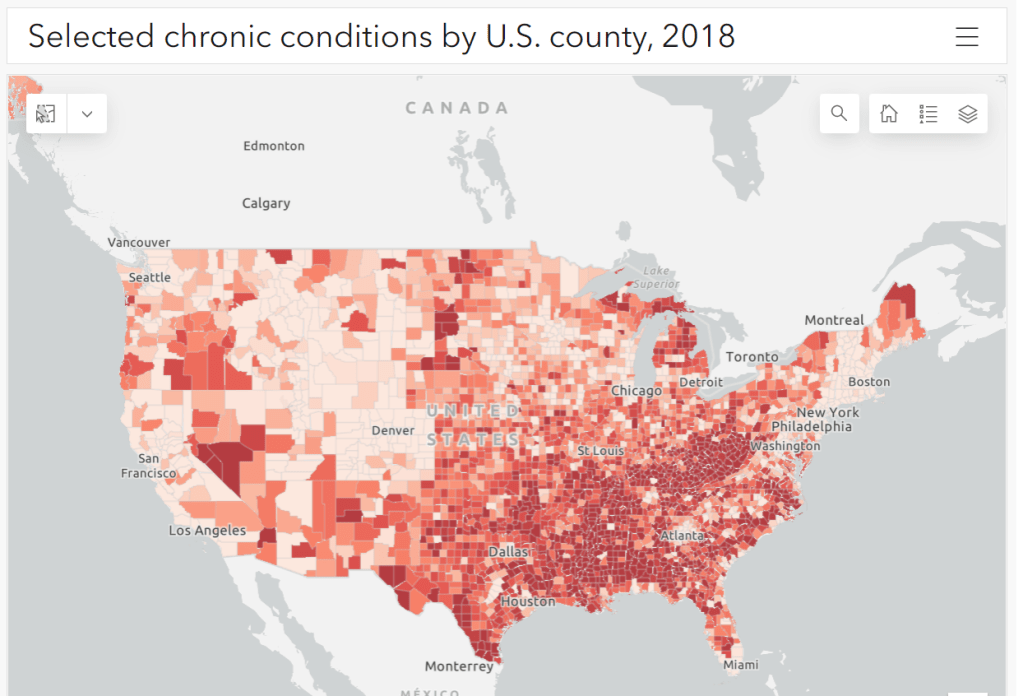

Parts of the South and Midwest have higher rates of chronic conditions (colored darker red on the map) that confer higher risk for severe COVID-19. Chart via the CDC. The U.S. has started a new booster shot campaign, this time using vaccines designed to specifically target super-contagious subvariants Omicron BA.4 and BA.5. (For more details on the shots themselves, see last week’s post.)

Unlike previous vaccination campaigns, these boosters are available to all adults across the country who have been previously inoculated. There was no prioritization for seniors, healthcare workers, or other higher-risk adults. The official guidance from the federal government is actually pretty straightforward, for once: everyone should get the new booster. And get a flu shot soon, too, possibly even at the same time as your COVID-19 shot.

But all previously-vaccinated Americans are not facing similar levels of COVID-19 risk. Many of the same qualifications that might have warranted you an earlier dose in spring 2021 should now lead you to prioritize your Omicron booster, even if you might have been infected recently. At the same time, people who fall in these groups (or who share their households) have a good reason to continue using other safety measures after their boosters.

Here are the major qualifications for higher risk, with data to back them up:

- Seniors, especially those over age 70: More than 90% of Americans over age 65 have received at least their primary vaccine series, according to the CDC, while over 70% have received at least one booster. Yet older Americans continue to have the highest rates of hospitalizations and deaths. For example, those older than 70 have consistently been hospitalized at several times the rate of younger adults (when adjusted for population). The same pattern is true for deaths among adults over age 75. Seniors who receive the new booster shots will face a lower risk of severe COVID-19 this fall and winter.

- Black, Indigenous, and other Americans of color, especially seniors: Despite dedicated vaccination campaigns and other health equity efforts, Americans of color have continued to be hit harder by the pandemic than white Americans. Higher rates of chronic conditions in minority populations combined with other socioeconomic factors (POC are more likely to work essential jobs, to lack healthcare, etc.) have led to disproportionately high hospitalization and death rates. And the U.S.’s booster shot campaigns so far have been inequitable, as shown in a recent study by demography experts. Reaching these populations should be a priority for the new Omicron boosters.

- Immunocompromised people: National estimates consider about 3% of Americans to be moderately or severely immunocompromised, meaning that their immune systems have limited capacity to respond to infections without medical assistance. This group includes cancer patients, organ transplant recipients, people with autoimmune diseases, and more. (This Yale Medicine article provides more information.) Immunocompromised people might have already had multiple booster shots but are still eligible to receive an Omicron booster as soon as possible, the CDC recommends.

- People with Long COVID and related conditions: While there isn’t as much established data in this area, I have seen a lot of anecdotal reports from Long COVID patients who work hard to avoid new coronavirus infections—concerned about reinfection’s possibility to worsen their symptoms. On the flip side, vaccination might lead to improvement in Long COVID patients, as the shot boosts a patient’s immune system in responding to lingering reservoirs of virus. The Atlantic covered this possibility when Long COVID patients were first eligible for vaccination in early 2021, and other studies since then have backed it up. More research is needed, but at the very least, Long COVID patients receiving a new booster will have lower risk of a new severe case.

- People with other preexisting health conditions: The CDC has an extensive list of medical conditions that can confer additional risk for severe COVID-19, with plenty of links to other CDC pages and medical sites where you can learn more about relevant evidence. I won’t go through them all here (that’s a topic for another week’s issue), but I do recommend checking out the CDC’s information and linked sources if you have a condition on the list. You can also explore this map of chronic condition rates by county.

More vaccination data

-

Pandemic preparedness: Improving our data surveillance and communication

Screenshot of the new Biden COVID-19 plan. As COVID-19 safety measures are lifted and agencies move to an endemic view of the virus, I’m thinking about my shifting role as a COVID-19 reporter. To me, this beat is becoming less about reporting on specific hotspots or control measures and more about preparedness: what the U.S. learned from the last two years, and what lessons we can take forward—not just for the future COVID-19 surges that are almost certainly coming, but also for future infectious disease outbreaks.

To that end, I was glad to see the Biden administration release a new COVID-19 plan focused on exactly this topic: preparedness for new surges, new variants, and new infectious diseases beyond this current pandemic.

From the plan’s executive summary:

Make no mistake, President Biden will not accept just “living with COVID” any more than we accept “living with” cancer, Alzheimer’s, or AIDS. We will continue our work to stop the spread of the virus, blunt its impact on those who get infected, and deploy new treatments to dramatically reduce the occurrence of severe COVID-19 disease and deaths.

The Biden plan was released last week, in time with the president’s State of the Union address. I read through it this morning, looking for goals and actions connected to data collection and reporting.

Here are a few items that stuck out to me, either things that the Biden administration is already doing or should be doing:

- Improving surveillance to identify new variants: The U.S. significantly improved its variant sequencing capacity in 2021, multiplying the number of cases sequenced by more than tenfold from the beginning to the end of the year. But the new Biden plan promises to take these improvements further, by adding more capacity for sequencing at state and local levels—and, crucially, “strengthening data infrastructure and interoperability so that more jurisdictions can link case surveillance and hospital data to vaccine data.” In plain language, that means: making it easier to track breakthrough cases (which I have argued is a key data problem in the U.S.).

- Expanding wastewater surveillance: As I’ve written before, in the current national wastewater surveillance network, some states are very well-represented with over 50 collection sites; while other states are not included in the data at all. The Biden administration is committed to bring more local health agencies and research institutions into the surveillance network, thus expanding our national capacity to get early warnings about surges.

- Standardizing state and local data systems: I’ve written numerous times that the U.S. suffers from a lack of standardization among its 50 different states and hundreds of local health agencies. According to the new plan, the Biden administration plans to facilitate data sharing, aggregating, and analyzing data across state and local agencies—including wastewater monitoring and other potential methods of surveillance that would provide early warnings of new surges. This would be huge if it actually happens.

- Modernize the public health data infrastructure: One thing that could help health agencies better coordinate and share data: modernizing their data systems. That means phasing out fax machines and mail-in reports (which, yes, some health departments still use) and investing in new electronic health record technologies, while hiring public health workers who can manage such systems.

- Use a new variant playbook to evaluate new virus strains: Also in the realm of variant preparedness, the Biden administration has developed a new “COVID-19 Variant Playbook” that may be used to quickly determine how a new variant impacts disease severity, transmissibility, vaccine effectiveness, and other factors. The new playbook may be used to quickly update vaccines, tests, and treatments if needed, by working in partnership with health systems and research institutions.

- Collecting demographic data on vaccinations and treatments: The Biden plan boasts that, “Hispanic, Black, and Asian adults are now vaccinated at the same rates as White adults.” However, CDC data shows that this trend does not hold true for booster shots: eligible white Americans are more likely to be boosted than those in other racial and ethnic groups. The administration will need to continue collecting demographic data to identify and address gaps among vaccinations and treatments; indeed, the Biden plan discusses continued efforts to improve health equity data.

- Tracking health outcomes for people in high-risk settings: Along with its health equity focus, the Biden plan discusses a need to better track and report on health outcomes in nursing homes, other long-term care facilities, and other congregate settings like correctional facilities and homeless shelters. Congregate facilities continue to be major COVID-19 hotspots whenever there’s a new outbreak, so improving health standards in these settings should be a major priority.

- Studying and combatting vaccine misinformation, vaccine safety: The new plan acknowledges the impact of misinformation on vaccine uptake in the U.S., and commits the Biden administration to addressing this trend. This includes a Request for Information that will be issued by the Surgeon General’s office, asking researchers to share their work on misinformation. Meanwhile, the administration will also continue monitoring vaccine safety and reporting these data to the public.

- Test to Treat: One widely publicized aspect of the Biden plan is an initiative called “Test to Treat,” which would allow people to get tested for COVID-19 at pharmacies, health clinics, long-term care facilities, and other locations—then, if they test positive, immediately receive treatment in the form of antiviral pills. If this initiative is widely funded and adopted, the Biden administration should require all participating health providers to share testing and treatment data. This would allow researchers to evaluate whether this testing and treatment rollout has been equitable across different parts of the country and minority groups.

- Website for community risk levels and public health guidance: The Biden plan includes the launch of a government website “that allows Americans to easily find public health guidance based on the COVID-19 risk in their local area and access tools to protect themselves.” The CDC COVID-19 dashboard was recently redesigned to highlight the agency’s new Community Level guidance, which is likely connected to this goal. Still, the CDC dashboard leaves much to be desired when it comes to comprehensive information and accessibility, compared to other trackers.

- A new logistics and operational hub at HHS: In the last two years, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) built up an office for coordinating the development, production, and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. The new Biden plan announced that this office will become a permanent part of the agency, and may be used for future disease outbreaks. At the same time, the Biden administration has added at-home tests, antiviral pills, and masks to America’s national stockpile for future surges; and it is supporting investments in laboratory capacity for PCR testing.

- Tracking Long COVID: Biden’s plan also highlights Long COVID, promoting the need for government efforts to “detect, prevent, and treat” this prolonged condition. The plan mentions NIH’s RECOVER initiative to study Long COVID, discusses funding new care centers for patients, and proposes a new National Research Action Plan on Long COVID that will bring together the HHS, VA, Department of Defense, and other agencies. Still, the plan doesn’t discuss actual, financial support for patients who have been out of work for up to two years.

- Supporting health and well-being among healthcare workers: The new Biden plan acknowledges major burnout among healthcare workers, and proposes a new grant program to fund mental health resources, support groups, and other systems of combatting this issue. Surveying healthcare workers and developing systematic solutions to the challenges they face could be a major aspect of preparing for future disease outbreaks. The Biden plan also mentions investing in recruitment and pipeline programs to support diversity, equity, and inclusion among health workers.

- More international collaboration: The new Biden plan also focuses on international aid—delivering vaccine donations to low-income nations—and collaboration—improving communication with the WHO and other global organizations that conduct disease surveillance. This improved communication may be especially key for identifying and studying new variants in a global pandemic surveillance system.

This week, a group of experts—including some who have advised the Biden administration— followed up on the Biden plan with their own plan, called “A Roadmap for Living with COVID.” The Roadmap plan also emphasizes data collection and reporting, with a whole section on health data infrastructure; here, the authors emphasize establishing centralized public health data platforms, linking disparate data types, designing data infrastructure with a focus on health equity, and improving public access to data.

Both the Biden administration’s plan and the Roadmap plan give me hope that U.S. experts and leaders are thinking seriously about preparedness. However, simply releasing a plan is only the first step to making meaningful changes in the U.S. healthcare system. Many aspects of the Biden plan involve funding from Congress… and Congress is pretty unwilling to invest in COVID-19 preparedness right now. Just this week, a $15 billion funding plan collapsed in the legislature after the Biden administration already made major concessions.

Readers, I recommend calling your Congressional representatives and urging them to support COVID-19 preparedness funding. You can also look into similar measures in your state, city, or other locality. We need to improve our data in order to be prepared for future disease outbreaks, COVID-19 and beyond.

More national data

-

Sources and updates, December 5

- State approaches to contact tracing: This report from the National Academy for State Health Policy, updated on December 2, explores how every U.S. state is approaching contact tracing for COVID-19 cases. The report includes state partnerships with research institutions, adjustments for case surges, workforce sizes and training, digital contact tracing apps, and more. (H/t Al Tompkins’ COVID-19 newsletter.)

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor (December update): The newest polling report from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor project is out this week, detailing public opinion on vaccinations, including booster shots, mandates, and more. Two notable findings: four in ten Republican adults are unvaccinated, and Republicans are less likely to report receiving a booster dose than Democrats.