- New vaccination data from the CDC: The CDC has started publishing vaccination data reflecting how many Americans have received COVID-19, flu, and RSV shots in fall 2023. These numbers are estimates, based on the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, as the agency is no longer directly compiling COVID-19 vaccinations from state and local health agencies. (See this post from last month for more details.) According to the estimates, about 28% of American adults have received a 2023 flu shot, compared to 10% who have received a 2023 COVID-19 shot. The numbers reflect poor communication about and accessibility challenges with this year’s COVID-19 vaccines.

- FDA approves a rapid COVID-19 test: Following the end of the federal public health emergency this spring, the FDA has advised companies that produce COVID-19 tests to submit their products for full approval, transitioning out of the emergency use authorizations that these tests received earlier in the pandemic. The FDA has now fully approved an at-home COVID-19 test: Flowflex’s rapid, antigen test. This is the second at-home test to receive approval, following a molecular test a few months ago. The Floxflex test “correctly identified 89.8% of positive and 99.3% of negative samples” from people with COVID-like respiratory symptoms, according to a study that the FDA reviewed for this approval.

- WHO updates COVID-19 treatment guidance: This week, the World Health Organization updated its guidance on drugs and other treatment options for severe COVID-19 symptoms. A group of WHO experts has regularly reviewed the latest evidence and updated this guidance since fall 2020. The update includes guidelines on classifying COVID-19 patients based on their risk of potential hospitalization, recommendations for drugs such as nirmatrelvir and corticosteroids, and recommendations against other drugs such as invermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Clinicians can explore the guidance through an interactive tool that summarizes the expert group’s findings.

- Gargling with salt water to reduce symptoms: Speaking of COVID-19 treatments: gargling with salt water may help people with milder COVID-19 symptoms recover more quickly, according to a new study presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s annual conference. The researchers compared COVID-19 outcomes among people who did and did not use salt water for 14 days while sick; those who used the treatment had lower risks of hospitalization and reported shorter periods of symptoms. This study has not yet been peer-reviewed and more research will be needed, but it’s still helpful evidence to back up salt water as a potential treatment (something I’ve personally seen recommended anecdotally in the last couple of years).

- Allergies as potential Long COVID risk factors: Another study that caught my attention this week: researchers at the University of Magdeburg in Germany conducted a review of connections between allergies and Long COVID. The researchers compiled data from 13 past papers, including a total of about 10,000 study participants. Based on these studies, people who have asthma or rhinitis (i.e. runny nose, congestion, and similar symptoms, usually caused by seasonal allergies) are at higher risk for developing Long COVID after a COVID-19 case. The researchers note that this evidence is “very uncertain” and more investigation is needed; however, the study aligns with reports of people with Long COVID getting diagnosed with mast cell activation syndrome (or MCAS, an allergy-related condition).

- Dropping childhood vaccination rates: One more notable study, from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): vaccination rates for common childhood vaccines are declining among American kindergarteners, according to CDC research. CDC scientists reviewed data reflecting the childhood vaccinations that are required by 49 states and D.C. for the 2022-23 school year, and compared those numbers to past years. Overall, 93% of kindergarteners had completed their state-required vaccinations last school year, down from 95% in the 2019-20 school year, while vaccine exemptions increased to 3%. In 10 states, more than 5% of kindergarteners had exemptions to their required vaccines—signifying increased risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in schools, according to the CDC.

Tag: vaccine access

-

Sources and updates, November 12

-

How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?

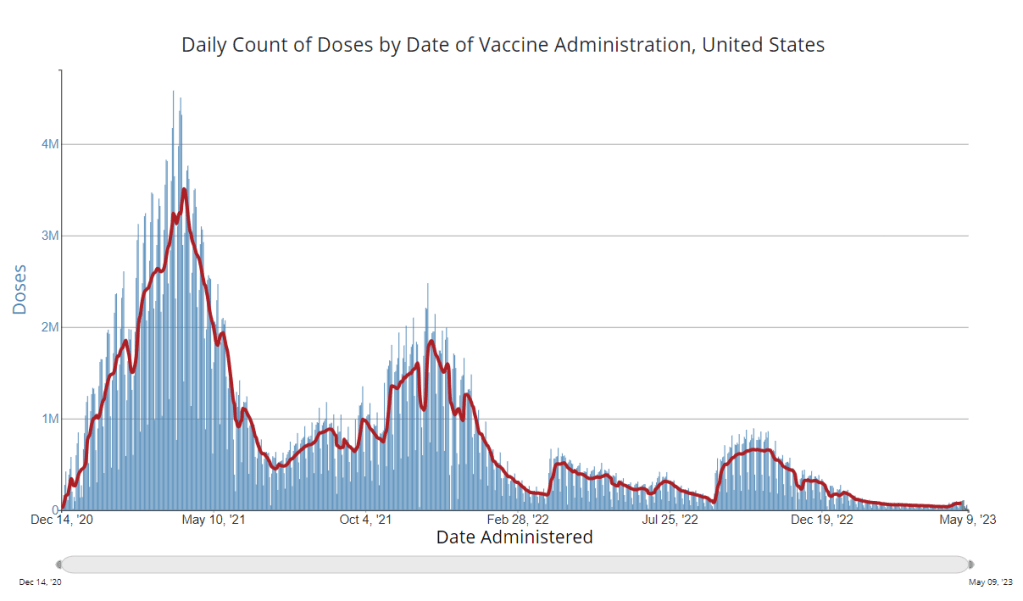

The CDC’s vaccination data pages all stopped updating in May 2023. How is the agency tracking our current round of shots? It’s now been a couple of weeks since updated COVID-19 vaccines became available in the U.S. At this point in prior COVID-19 vaccine rollouts, we would know a lot about who had received those vaccines: data would be available by state, for different age groups, and other demographic categories.

This time, though, the data are missing on a national scale. Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards.

But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations. In fact, last week, the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) told reporters that more than seven million Americans have received updated COVID-19 vaccines so far this fall.

HHS also said that about 14 million doses have been shipped to vaccination sites, primarily pharmacies. In addition, 710,000 vaccines for children have been ordered through a federal program that provides these shots.

Vaccine distribution numbers are slightly easier for the CDC and HHS to collect, as they can work directly with vaccine manufacturers. To understand how many people are getting the shots, though, is more challenging—requiring a mix of data from state and local agencies, surveys, and other surveillance mechanisms.

What changed with the PHE’s end:

Early in the pandemic, the CDC established data-sharing agreements with the health agencies that keep immunization records. This includes all states, territories, and a few large cities (such as New York City and Philadelphia) that have separate records systems from their states; you can see a full list of records systems here.

Through those agreements, the CDC collected vaccine administration numbers, standardized the data (as much as possible), and reported them on public dashboards. The CDC wasn’t able to collect as detailed demographic information as many health experts would’ve liked—for example, they never reported vaccinations by race and ethnicity below the national level. But the data were still useful for tracking who got vaccinated across the U.S.

These data-sharing agreements concluded with the end of the public health emergency (PHE) in May 2023. According to a CDC report published at that time, the CDC was able to extend agreements with some jurisdictions past the PHE’s end. Still, the report’s authors acknowledged that “future data might not be as complete” as during the emergency period. Even if 40 out of 50 states keep reporting, the remaining 10 represent data gaps.

Notably, the May report also claims that the CDC would continue to provide data on COVID-19 vaccination coverage on the CDC’s COVID-19 dashboard and a separate vaccination dashboard. But neither of those dashboards has been updated with any information from this fall’s vaccine campaign, as of this publication.

In addition to compiling data from state and local systems, the CDC has other mechanisms for tracking vaccinations. According to CBS News reporter Alexander Tin, CDC officials highlighted a couple during a briefing on October 4:

- The National Immunization Survey, a phone survey conducted by CDC officials to estimate national vaccination coverage based on a representative sample of Americans. This survey is currently the CDC’s method for tracking flu vaccinations.

- CDC’s Bridge Access and Vaccines for Children (VFC) programs, both of which buy vaccines to distribute to Americans who may not have health insurance or face other financial barriers to vaccination. The Bridge Access program was specifically set up for COVID-19 vaccines, while the VFC program covers other childhood vaccines.

- Contact with vaccine manufacturers and distributors, i.e. the pharmaceutical companies that make the vaccines and the pharmacies and healthcare organizations that give them out. These companies share data with the CDC, offering insights into how many vaccines have been distributed to different locations; though the data may not be comprehensive if not all distributors are included (i.e. just big pharmacy chains, not smaller, independent stores).

Other places to look for vaccination data:

Outside of the CDC, there are a few other places where you can look for vaccination data. Here are a couple that I’m monitoring:

- State and local public health agencies: Some agencies that track immunizations have their own dashboards, reporting on vaccinations in a specific state or locality. For example, New York City’s health department tracks COVID-19 vaccinations among city residents, although the agency hasn’t yet published data for this fall’s vaccines. I have a list of state vaccination dashboards here; this doesn’t currently represent data on the fall 2023 vaccines, but I aim to do that update in the coming weeks.

- Outside surveys, such as KFF’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Like the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, other health organizations conduct surveys to track vaccinations. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is one well-known project, which has been doing regular surveys on COVID-19 vaccine uptake since December 2020.

- Scientific reports answering specific vaccination questions: Public health researchers may use surveys, immunization records, or other data systems to study specific questions about vaccination, such as the impact that vaccination has on lowering a patient’s risk of severe disease. These studies are often published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and other journals.

If you have other questions about vaccination data—or want to share a data source I didn’t mention here—please reach out: email me or leave a comment below.

-

Sources and updates, October 8

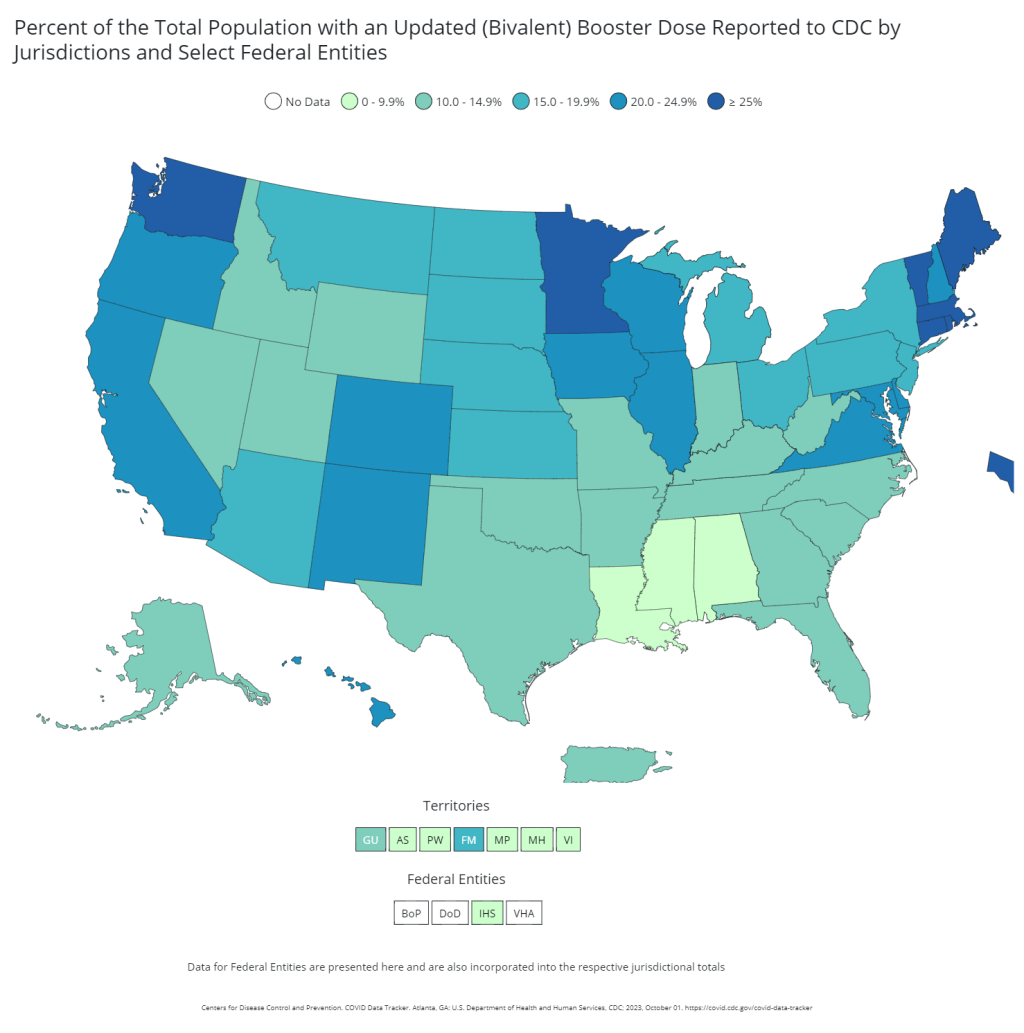

- Vaccination disparities in long-term care facilities: A new study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report shares vaccination patterns from about 1,800 nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care facilities across the U.S., focusing on the bivalent booster (or, last fall’s vaccine). The CDC researchers found significant disparities in these vaccinations: vaccine coverage was lowest among Black and Hispanic residents compared to other demographics, and was lowest in the South and Southeast compared to other regions. Future vaccination campaigns need to make it easy for these groups to get their shots, the authors suggest; but based on how the 2023 rollout has gone so far, this trend seems likely to continue.

- Reasons for poor bivalent booster uptake: Speaking of last fall’s boosters, a study from researchers at the University of Arizona suggests reasons why people didn’t get the shots last year. Researchers surveyed about 2,200 Arizona residents who had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Among the survey respondents who didn’t get last year’s booster, the most common reason for not doing so was a belief that a prior infection made the shot unnecessary (40%), concerns about vaccine side effects (32%), believing the booster wouldn’t provide additional protection over prior shots (29%), and safety concerns (23%). As with the study above, this paper shows weaknesses in the U.S.’s recent vaccine promotion strategies.

- At-home tests are useful but far from perfect: Researchers at Nagoya University and the University of Oxford used mathematical models to study how different safety measures impact chances of COVID-19 outbreaks. The researchers developed models based on contact tracing data reflecting how Omicron spreads through groups. Rapid, at-home, antigen tests are a useful but imperfect method for reducing outbreak risk, the study found, with daily testing reducing the risk of a school or workplace outbreak by 45% compared to a scenario in which new cases are identified by symptoms only. “In high-contact settings, or when a new variant emerges, mitigations other than antigen tests will be necessary,” one of the scientists said in a statement.

- Long-term symptoms from non-COVID infections: The prevalence of Long COVID has led many scientists to develop new interest in chronic conditions that may arise after other common infections, such as the flu and other respiratory viruses. One recent study from Queen Mary University of London identifies a potential pattern, using data from COVIDENCE UK, a long-term study tracking about 20,000 people through monthly surveys. Researchers compared symptoms between people who had a COVID-19 diagnosis and those with other respiratory infections, looking at the month following infection. They found similar risks of health issues in the one-month timeframe for both groups, though specific symptoms (loss of taste and smell, dizziness) were more specific to Long COVID. Of course, some people in the “non-COVID” group could have had COVID-19 without a positive test; still, the data indicate more, longer-term research is needed.

- Autoimmune disorders following COVID-19: In another Long COVID-related paper, researchers at Yonsei University and St. Vincent’s Hospital in South Korea found that patients had increased risks of autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders following COVID-19 cases. The study used patient records from South Korea’s national public health system, comparing about 354,000 people who had COVID-19 diagnoses to 6.1 million controls. COVID-19 patients had a significant risk of new autoimmune issues within several months after infection; new diagnoses included alopecia (or hair loss), Crohn’s disease (inflammatory bowel issues), sarcoidosis (overactive immune system), and more. These conditions should be considered by doctors evaluating potential Long COVID patients, the researchers wrote in their paper.

- New climate vulnerability index: This last item isn’t directly COVID-19 related, but may be useful in evaluating community risks for public health threats. The Environmental Defense Fund, Texas A&M University, and other partners have launched the U.S. Climate Vulnerability Index, a database providing Census tract-level information about how our changing climate will impact different communities. Communities are ranked from low to high climate vulnerability, with detailed data available on sociodemographic characteristics as well as potential extreme weather events and health trends.

-

COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now available

This week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC’s fall vaccine recommendations were already set up to include Novavax once it was authorized, so pharmacies and health providers can start administering it without any additional hurdles at the federal level.

Novavax’s new vaccine, like the options from Pfizer and Moderna for this fall, is designed to protect against XBB.1.5, a recently circulating variant that is closely related to most of the strains causing disease in the U.S. right now. But unlike the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines (which use mRNA technology), Novavax’s uses a piece of viral spike protein to teach recipients’ immune systems how to recognize the coronavirus.

Some scientists and health advocates I follow have been particularly looking forward to the Novavax authorization, hoping to get their shot rather than one of the mRNA options. There are two main reasons for this choice, based on my reading:

- The Novavax vaccine may have fewer or easier side effects than the mRNA vaccines. This is particularly appealing for some people who had poor reactions to earlier mRNA vaccine doses (including, in some cases, long-term issues similar to Long COVID), and some people with chronic conditions.

- Some experts say that “mixing and matching” different types of vaccines might lead to a more robust, long-term immune response against the coronavirus, compared to sticking with one vaccine type.

A recent article in Science goes into more detail about these considerations. Writer Jennifer Couzin-Frankel walks through scientific studies that look at Novavax compared to the other vaccine options, and explains some of the questions that we don’t have sufficient data to answer yet. For example, as fewer people have received Novavax vaccines compared to the mRNA options, it’s harder to see signals for potential rare adverse reactions. More studies are coming in that will help address these questions, but for now, many people are making personal choices about which vaccine to get this fall.

-

Sources and updates, October 1

- CDC publishes Long COVID data from national survey: Every year, the CDC conducts the National Health Interview Survey, a detailed look at population health in the U.S. through interviews of about 30,000 adults and 9,000 children. In 2022, the survey included questions about Long COVID, defining the condition as symptoms for at least three months after an initial COVID-19 case. This week, the CDC published data from the 2022 survey. Among the findings: about 6.9% of adults had ever experienced Long COVID, and 3.4% had it at the time of their interview. These figures were 1.3% and 0.5% for children, respectively. Women were more likely to experience it than men, and the survey identified other demographic differences (race, income, etc.). While many of the findings align with other Long COVID data, this CDC survey is unique in providing data on Long COVID in kids—which can be devastating for the small (yet significant) number of people impacted.

- Molnupiravir could lead to new coronavirus mutations: A new study, posted in Nature this week ahead of its final publication, identifies potential dangers of using the antiviral molnupiravir. (Molnupiravir, made by Merck, is a similar drug to Paxlovid but tends to be less effective, so it’s not used as widely.) For this study, researchers at the University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, and colleagues examined coronavirus sequence data and found that certain mutations were likely to increase after molnupiravir use. Researchers have already known that this antiviral could lead to more viral evolution, but the paper provides more details on specific mutation risks; further research may examine the drug’s implications for immunocompromised patients.

- Accessibility issues for COVID-19 websites: Many state and territorial COVID-19 websites don’t meet accessibility guidelines, making their key health information difficult for people who are blind or visually impaired to access, according to researchers at North Carolina State University. The researchers recently replicated a study that they’d first done in 2021, running checks on state sites against standard web accessibility guidance. “In 2021, none of these public-facing COVID-19 sites met all the checked WCAG guidelines, and things did not get any better in 2023,” study author Dylan Hewitt said in a statement. Issues include incompatibility with screen readers, limited color contrast, and no alt text for images.

- Polling data indicate higher interest in flu shots than COVID-19 shots: The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) has published a new round of polling data from its COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, focusing on vaccinations this fall. About 58% of adults in the poll said they would get a flu shot this year, compared to 47% who said they would get an updated COVID-19 shot. Vaccine interest continues to be partisan, the poll suggested, with Democrats much more likely to express confidence in the updated COVID-19 vaccines’ safety than Republicans. Democrats were also more likely to respond to increased COVID-19 spread, with 58% of those polled saying they recently took more precautions in response to the surge this summer.

- New behavioral health survey data from the CDC: One more CDC update from this week: the agency has just published 2022 data from its Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). The BRFSS involves interviews of more than 400,000 adults each year, including questions about alcohol use, tobacco use, immunizations, cancer screenings, mental health, and more. While the data aren’t directly related to COVID-19, this surveillance system may be a valuable source for reporters or researchers seeking contextual data about health behaviors in a particular state, city, or county.

-

COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.

Last year, just 17% of the U.S. population received a bivalent booster. Will this year’s uptake be better? Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.

I’ve published the full responses in the table below. Here are a few common themes that I saw in these stories:

- Pharmacies aren’t receiving enough vaccines. Several readers shared that their pharmacies had inadequate vaccine supply to accommodate all the people who made vaccination appointments, or who wanted appointments. Vaccine supply may also be unpredictable—a pharmacy may think they’re getting more shots, but in fact not receive them—leading to appointment cancellations.

- Insurance providers weren’t prepared for this vaccine rollout. Despite months of advance notice that a fall COVID-19 vaccine was coming, many insurance companies apparently failed to prepare billing codes or other system updates that would allow them to cover the shots. A couple of people who shared insurance issue stories are on Medicare—representing a population (i.e. seniors) who should be at the front of the vaccine line.

- Very limited, confusing vaccine availability for young kids. Several readers shared that they were able to get vaccinated, but their children under 12 have not received a vaccine yet. While the FDA and CDC have authorized this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines for all Americans ages six months and older, younger children require a different vaccine formulation from adults. And this formulation appears either entirely unavailable or very difficult to access, depending on where you live.

- People living in less dense areas may need to travel. A few readers shared that, as they searched for vaccine appointments in their areas, the closest pharmacies with doses available were miles away—over 10 miles, in one case. This is a significant barrier for people fitting vaccine appointments into their work schedules.

- Information may be inconsistent. Vaccine availability listed in one place (such as a pharmacy chain’s website or the federal vaccines.gov website) may be inaccurate in another. Some readers shared that they spent extra time on the phone with pharmacies or health providers to get accurate information—another barrier.

- Pharmacies don’t have enough staff for this. Even readers who were able to receive COVID-19 vaccines often had to wait a long time at their pharmacies. Several shared that their pharmacies appeared to be understaffed, dealing with the COVID-19 shots along with routine prescriptions and other duties. The days of mass vaccination sites, efficiently run by public health departments, are long over.

- Kaiser Permanente members face delays. One company that appears to be causing outsized problems is Kaiser Permanente, one of the biggest insurers and health providers on the West Coast. Several readers shared that Kaiser was not providing new COVID-19 vaccines until early October, and would not cover the shots if their members went to another location. That’s a big delay, and it may be further impacted by a coming strike at the company.

- These vaccines are expensive. If you decide to pay for a COVID-19 shot out-of-pocket (as some readers did), it costs almost $200. Even the federal government is paying about triple the cost of last year’s COVID-19 vaccines per shot, for the doses it is covering, STAT News reports. The U.S. may have received a “bad deal” here, STAT suggests, considering all of the federal funding that’s supported vaccine research and development.

As I wrote last week, some news outlets have covered these challenges, but this issue really deserves more attention. The updated COVID-19 vaccines are basically the U.S. government’s only strategy to curb a surge this winter, and they should be easily, universally accessible. Instead, many people eager to get vaccinated are going through multiple rounds of appointments, phone calls, pharmacy lines, and more.

For every one of these readers who has persisted in getting their shot, there are likely many other people who tried once and then gave up. And those people who don’t receive the vaccine will be at higher risk of severe illness, death, and long-term symptoms from COVID-19 this fall and winter. This is a public health failure, plain and simple.

And it’s important to emphasize that this failure is not surprising. Many health commentators predicted that these challenges would arise as the federal public health emergency ended and COVID-19 tools transitioned from government-funded to covered-by-insurance. For more context on why this is happening, I recommend the Death Panel podcast’s latest episode, “Scenes from the Class Struggle at CVS.”

If you’re a reporter who would like to connect with one of the COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers who shared a story, please email me at betsy@coviddatadispatch.com. Most of the people in the database below shared an email or other contact info.

[table id=10 responsive=collapse responsive_breakpoint=all /] -

Did you have a hard time getting an updated COVID-19 vaccine? Tell us about it.

In the last week, my social media feeds have been full of stories about vaccine access issues. Even though the updated COVID-19 vaccines are supposed to be free—either covered by insurance plans or by a federal program—people keep getting bills. Or their vaccine appointments are canceled unexpectedly. Or they can’t get an appointment at all.

Some news outlets have covered these access challenges, but far more attention is needed. The new vaccines are the U.S. government’s only real strategy to curb a likely COVID-19 surge this winter, now that masks, testing, and other tools are far less available. It is absolutely crucial that as many people get vaccinated as possible, and any barriers to those vaccinations deserve front-page headlines.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch may not have the reach of an established national media outlet, but with the help of all of you readers, we can help draw more attention to this massive problem. If you have had a hard time getting an updated COVID-19 shot, please share your experience: you can use this Google form, email me, or reach out on social media (Twitter, Bluesky, Mastodon).

You can share your vaccination experience anonymously or attach your name, location, or other details, if you’d like. (There are no required fields on the Google form.) Next week, I’ll publish the responses in a public database on the CDD website. My hope is that this compilation can show how widespread these vaccine access issues are, and can serve as a resource for other journalists who might be interested in covering the problem.

Also, a PSA: if a pharmacy or doctor’s office tries to charge you for a COVID-19 vaccine, remind them that the vaccines are free. You can refer them to the CDC’s Bridge Access Program, which will pay for any vaccinations not covered by insurance.

-

New COVID-19 vaccines are now available: 10 key facts and statistics about these shots

Data from a CDC presentation suggest that people of all ages, including children, receive a benefit from updated COVID-19 vaccines. We now have two new COVID-19 vaccines available for this year’s respiratory virus season, one from Pfizer and one from Moderna, which are expected to perform well against current variants. The FDA approved both vaccines this week, and the CDC recommended them for almost all Americans. A third option, from Novavax, may become available in the coming weeks as well.

The federal government aims to present this fall’s shots as the next iteration in routine, annual COVID-19 vaccines—similar to the routine we’re all used to for flu shots. In fact, I’ve seen some news suggesting that the federal health agencies don’t want us to call these shots “boosters,” instead calling them “updated” shots or annual shots.

But this fall’s vaccine rollout is likely to be anything but routine, as it’s the first rollout following the end of the federal COVID-19 public health emergencies. The government is no longer purchasing shots and distributing them for free; now, insurance companies will have to cover the shots.

As a result, many Americans—especially those without health insurance—will have a harder time accessing these vaccines than they have for previous shots. Plus, the federal emergency’s end will make it harder for us to track how the vaccines are performing, as the coronavirus continues to evolve into new variants.

With all of these complications in mind, here are ten key facts and statistics that you should know about this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines.

Pfizer and Moderna’s shots have been approved and recommended for all Americans, ages six months and older.

Despite some debates among scientists about whether younger people really need updated COVID-19 shots, the FDA has approved these vaccines—and the CDC has recommended them— for all age groups. This is important because CDC recommendations are often the basis for insurance coverage, as experts explained at a webinar hosted by the National Press Foundation on Tuesday.

The shots exclusively target XBB.1.5, a coronavirus lineage that is common in the U.S. and globally right now.

According to the CDC’s genomic surveillance program, almost all cases in the U.S. in recent weeks have been caused by XBB.1.5 or related variants from the XBB lineage. Variants like EG.5 and FL.1.5.1 are also XBB descendants, which have been given nicknames to make it a bit easier for scientists to keep track of them.

It’s also important to note that, unlike last year’s boosters, this fall’s shots are monovalent vaccines—meaning they only target XBB.1.5. The shots no longer target the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 that first circulated in 2020. Scientists generally approve of this choice, as the virus has mutated so much since that time.

Moderna’s booster led to a 17-fold increase in antibodies against XBB.1.5 and XBB.1.6.

The vaccine companies presented data to the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee on Tuesday. Moderna’s presentation included results from a study testing its new vaccine against several different variants, using blood samples from people who received the booster.

About one month after vaccination with Moderna’s booster, the participants had about 17.5 times more neutralizing antibodies against XBB.1.5, 16.7 times more against XBB.1.6, 14 times more against EG.5.1, and 10 times more against BA.2.86. Pfizer also presented data, suggesting that their vaccine should similarly perform well against current variants.

The new vaccines should lead to similar side effects as we’re used to from past mRNA shots.

Based on data that the vaccine companies presented to the CDC’s committee, this fall’s Pfizer and Moderna vaccines should lead to similar side effects—headache, fatigue, muscle pain, etc.—as many of us have expected from past rounds of COVID-19 shots. The companies, along with the CDC and FDA, will continue to monitor these vaccines for any safety issues that may emerge as people start to get them.

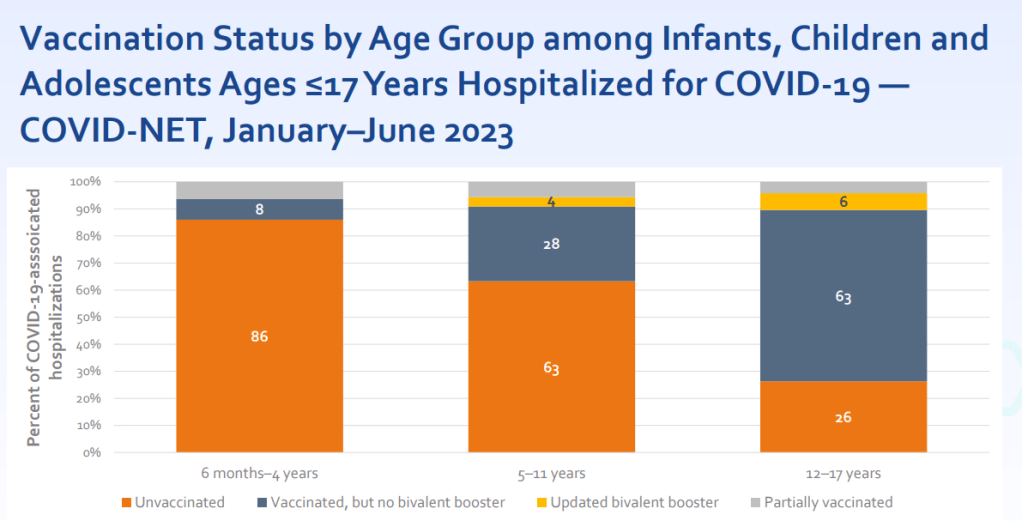

Young, unvaccinated children are at higher risk for COVID-19.

One of the CDC presentations focused on how this fall’s vaccines may benefit young children. Last fall and winter, hospitalization rates were higher for COVID-19 than for the seasonal flu across all young age groups, from infants (under six months) to 12-17 years old. The vast majority of the children hospialized were not vaccinated or hadn’t received last year’s booster.

For some CDC advisory committee members, these data were convincing in suggesting that this fall’s vaccine should be recommended for children, experts told STAT News. Vaccines updated to match current variants have a clear benefit for all age groups.

Long COVID remains a significant risk for Americans across age groups.

Another CDC presentation discussed Long COVID, as one of the potential adverse outcomes of a COVID-19 case. The CDC shared new data from a national survey conducted in 2022, which suggests that 9% of Americans ages 35 to 49 have experienced Long COVID symptoms (defined as symptoms lasting at least three months after a COVID-19 case). Adults ages 50-64 and 18-34 also reported high levels of Long COVID, at 7.4% and 6.8% ever experiencing symptoms, respectively.

Many studies have shown that vaccination lowers risk of Long COVID, though it does not by any means eliminate this risk. While it’s good to see the CDC incorporating Long COVID into its vaccine risk/benefit discussions, much more research is needed to better understand how to prevent this debilitating condition.

A Novavax vaccine is still in the pipeline.

Novavax also presented data to the CDC’s advisors this week, suggesting that its vaccine (also based on XBB.1.5) should perform similarly to the Pfizer and Moderna options. But unlike the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, Novavax’s has yet to receive FDA approval. The company has said it’s still planning to distribute its vaccine this fall, but it’s unclear when the FDA may authorize it.

Some people are eager to receive the Novavax vaccine this fall, rather than Pfizer or Moderna’s, because this vaccine uses a different mechanism to boost the immune system. It may also lead to fewer side effects than the mRNA vaccine, making it a potentially good option for people who’ve had particularly strong reactions. (I know a couple of readers have sent me questions about this, and aim to do a deep-dive on Novavax in a future issue.)

Only 17% of Americans received last fall’s bivalent booster.

The booster uptake last year was low, according to the CDC. Even among seniors, only 43% received the booster. Can we do better this year?

A POLITICO/Morning Consult poll found that about 60% of respondents said they “probably or definitely” would get this year’s vaccine. (The poll included about 2,000 registered voters from across the U.S.) But it’s likely that access issues could get in the way for many people, as getting this COVID-19 vaccine will be much more challenging than it’s been in past rollouts.

HHS program should provide free vaccines for 25-30 million adults.

The Department of Health and Human Services has officially launched its “Bridge to Access” program, designed to provide free COVID-19 shots to uninsured Americans. Through this program, the HHS is essentially buying a small number of shots and distributing them to pharmacies, federally supported health centers, and other providers. You should be able to view these providers at vaccines.gov, according to the HHS. But I’ll be curious to see how well that actually works.

This year’s vaccine rollout will be much harder to track.

In the past, I’ve written about how the U.S. has failed to monitor breakthrough cases, or COVID-19 infections that occur after someone is vaccinated (and the hospitalizations, deaths, and long-term symptoms that may result). This year, not only are we failing to track breakthrough cases—the U.S. no longer has any national case data at all. We also no longer have vaccination data, as the CDC is not collecting this information from state and local health systems.

So, how will we know how this year’s vaccine rollout goes? It’ll likely be a lot of guesswork, extrapolating from a few state/local health departments, polling data, and other smaller-scale research to estimate how many people are getting vaccinated nationally. This challenge is just another example of the damage that the federal government has done in the last year by dismantling many of its COVID-19 data systems.

-

Answering reader questions: Incubation period, vaccines coming this fall, nasal sprays

I received a couple of reader questions in recent weeks that I’d like to answer here, in the hopes that my responses will be more broadly helpful. As a reminder, if you ever have a COVID-19 question that you’d like to ask, you can email me at betsy@coviddatadispatch.com, or send it anonymously through this Google form.

COVID-19’s incubation period

One reader asked:

I’d love to learn more about COVID’s incubation period. I have read that it’s 2 to 14 days … but the median time seems to be on the low end (and could be as low as 24 hours?) How likely is it that it’s more like 14 days? I’d love to better understand this so that I know how to better handle exposures… Should I avoid someone who has had an exposure for two full weeks?

This is a tricky question for two reasons. First, the incubation period—or the time between exposure to COVID-19 and starting to show symptoms of infection—does indeed vary a lot. One review of studies on this topic, posted as a preprint in May, found a range from two to seven days, though it can be even longer. The CDC recommends precautions for up to ten days after exposure.

Second, the incubation period has changed as the coronavirus has mutated. The virus is constantly evolving to keep infecting us even as people build up immunity; shortening the incubation period is one of its strategies. Omicron has a notably shorter period than past variants; Katherine Wu at The Atlantic wrote an article about this in December 2021 that I think is still informative.

The preprint I cited above found that Omicron had an average incubation period of 3.6 days, shorter than other variants. I think it’s reasonable to assume that this period has continued to get shorter as Omicron has evolved into the many lineages we’re dealing with now. But the pace of research on this topic has slowed somewhat (with less contact-tracing data available for scientists to work with), so it’s hard to say for certain.

So, with these complexities in mind, how should one handle exposures? My personal strategy for this (noting that I’m not a doctor or qualified to give medical advice, just sharing my own experience) is to rely on a combination of timing, testing, and symptom monitoring. For the first couple of days after exposure, you wouldn’t be likely to have a positive test result even if you are infected, as it takes time for enough virus to build up in the body for tests to catch it. So, for those days, I’d just avoid people as much as possible.

After three to four days, PCR tests would start to be effective, and after five to six days, rapid tests would be. So at that point, I’d start testing: using a mix of PCR and rapid tests over the course of several days, up to two weeks after exposure. Studies have shown that the more tests you do, the more likely you are to catch an infection (and this applies to both PCRs and rapids). Daily is the best strategy, but less frequent regimens can still be useful if your access to tests is limited. At the same time, I’d keep track of any new symptoms, as that can be a sign of infection even if all tests are negative.

I’d personally be comfortable hanging out with someone who has had an exposure but consistent negative test results and no symptoms. But others who are less risk-tolerant than I am might avoid any contact for two weeks. The type of contact matters, too: a short, outdoor meeting or one with masks on is safer than a prolonged indoor, no-mask meeting.

Vaccine effectiveness

Another reader asked:

Is there any information on the effectiveness of the latest vaccines, including vaccines that combine Covid and RSV, and are there similarities between these viruses (related?)

As we head into respiratory virus season in the U.S., there will be, for the first time, vaccines available for all three major diseases: COVID-19, the flu, and RSV. I’ll talk about effectiveness for each one separately, because they are all separate vaccines for separate viruses. There’s no combined COVID-RSV vaccine on the market.

COVID-19: We know the fall boosters will target XBB.1.5, a variant that has dominated COVID-19 spread in the U.S. recently. There isn’t much data available on these vaccines yet, because the companies developing them (Pfizer, Moderna, Novavax) have yet to present about their boosters to the FDA and CDC, as is the typical process. The CDC’s vaccine advisory committee is meeting this coming Tuesday to talk fall vaccines, though, so it’s likely we will see some data from that meeting.

Also worth noting: some early laboratory studies suggest that vaccines based on XBB.1.5 will provide good protection against BA.2.86, despite concerns about differences between these variants. (More on this later in today’s issue.)

Flu: Every year, scientists and health officials work together to update flu vaccines based on the influenza strains that are circulating around the world. Effectiveness can vary from year to year, depending on how well the shots match circulating strains.

This week, we got a promising update about the 2023 flu vaccines: CDC scientists and colleagues studied how well these shots worked in the Southern Hemisphere, which has its flu season before the Northern Hemisphere. The vaccine reduced patients’ risk of flu-related hospitalization by 52%, based on data from several South American countries that participate in flu surveillance. This is pretty good by flu vaccine standards; see more context about the study in this article from TIME.

RSV: There are two new RSV vaccines that will be available this fall, both authorized by the FDA and CDC in recent months. These vaccines—one produced by Pfizer, one by GSK—both did well in clinical trials, reducing participants’ risks of severe RSV symptoms by about 90% (for the first year after infection, with effectiveness declining over time).

Both vaccines were authorized specifically for older adults, and Pfizer’s was also authorized for pregnant people as a protective measure for their newborns. We’ll get more data about these vaccines as the respiratory virus season progresses, but for now, experts are recommending that eligible adults do get the shots. This article from Yale Medicine goes into more details.

Nasal sprays as COVID-19 protection

Another reader asked:

I’m thinking of researching what foods and supplement are anti-viral anti-COVID. I’m wondering if anyone has done any research on that?

I haven’t seen too much research on about foods and supplements, since dietary options are usually not considered medical products for study. Generally, having a healthy diet can be considered helpful for reducing risk from many health conditions, but it’s not something to rely on as a precaution in the same way as you might rely on masking or cleaning air.

Another thing you might try, though, would be nasal sprays to boost the immune system. I have yet to try these myself, but have seen them recommended on COVID-19 Safety Twitter and by cautious friends. The basic idea of these nasal sprays is to kill viruses in one’s upper respiratory tract, essentially blocking any coronavirus that might be present from spreading further. People take these sprays as a preventative measure before potential exposures.

A couple of references on nasal sprays:

- Does nitric oxide nasal spray (Enovid/VirX/FabiSpray) help prevent or treat COVID-19? (Those Nerdy Girls)

- As COVID market narrows, SaNOtize moves to carve a new one: over-the-counter prevention (Fierce Biotech)

- Clinical efficacy of nitric oxide nasal spray (NONS) for the treatment of mild COVID-19 infection (Scientific paper in The Journal of Infection)

-

Sources and updates, August 20

- New toolkit for estimating COVID-19 risk from wastewater: Researchers at Mathematica published a new, open-source toolkit for interpreting wastewater data. It includes an algorithm that scientists and health officials can use to identify when a new surge might be starting based on wastewater results, as well as a risk estimator tool that combines wastewater data with healthcare metrics. The researchers developed this toolkit using data from North Carolina during the Delta and Omicron surges; their paper in PNAS last month describes it further, as does a blog post by the Rockefeller Foundation (which funded the project). This tool doesn’t provide real-time updates, as it only includes wastewater data through December 2022, but it offers a helpful model for using this source to inform public health policies.

- Vaccine delays for uninsured Americans: The CDC estimates that new COVID-19 boosters will become available in late September or early October, as I wrote last week. But Americans without health insurance may have to wait longer to get the shots or pay a hefty price tag, according to recent reporting from POLITICO. A federal government program with national pharmacy chains, which will provide the shots for free to uninsured people, is not slated to start until mid-October. Instead, uninsured people will need to pay out-of-pocket or find one of a small number of federal health centers to get vaccinated; this is likely to discourage vaccinations, POLITICO reports. And the number of uninsured people is only growing thanks to Medicaid redeterminations.

- Budget cuts at the CDC could mean layoffs: A recent op-ed in STAT News, written by two researchers familiar with the CDC’s organizational structure, warns that budget cuts at the agency could lead to a significant reduction in public health workers. The CDC’s budget was cut as part of the federal government’s debt ceiling negotiations last month, the authors explain. It faces a cut of about 10%, or $1.5 million a year, which could lead to significant layoffs. The reduced jobs are particularly likely to impact staff at the state and local levels, the op-ed’s authors argue, rather than at the CDC’d headquarters in Atlanta. “Reductions there will cut public health services and will have their greatest impact on the most vulnerable populations,” they write.

- Vaccine effectiveness for young children: Speaking of the CDC: the agency published a study this week in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report describing COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness for the youngest children who are eligible (i.e. under five years old). Researchers at the CDC and partners at healthcare centers across the country tracked COVID-related emergency department and urgent care visits among young children, from July 2022 through July 2023. Effectiveness for the primary series was low: Moderna’s two-dose series scored just 29% effective at preventing ED and urgent care visits, while Pfizer’s three-dose series was 43% effective. Children who received a bivalent (Omicron-specific) follow-up dose were much more protected, however: this regimen was 80% effective. Bivalent boosers should be a priority for young kids along with adults, the study suggests.

- Immune system changes following COVID-19: Another notable study from this week, from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and other institutions, describes how severe COVID-19 cases may damage patients’ immune systems. The researchers analyzed how specific genes were expressed in immune system cells taken from people who had severe cases of COVID-19. They found expression changes as long as a year after patients’ initial infections, and connected those changes to inflammation, organ damage, and other long-term issues. These genetic changes may point to one cause for Long COVID symptoms, though the study is somewhat limited by its focus on patients who had severe symptoms early on (as most people with Long COVID have initially milder cases).

- Smell and taste loss following COVID-19: While smell loss has long been considered a classic COVID-19 symptom, a new study shows that taste loss is also common, even among people who don’t lose their sense of smell. Researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center (a nonprofit center in Philadelphia) studied these symptoms through an online survey, which included about 10,000 participants between June 2020 and March 2021. COVID-positive participants were more likely to report smell issues, taste issues, and both together, compared to people who didn’t get sick, the researchers found. Their survey methodology—which included asking people to self-assess their senses by smelling common household objects—could be used for further large-scale studies of these symptoms, the researchers write.