Last week, I gave you an overview of the changes coming with the end of the federal public health emergency (PHE), highlighting some shifts in publicly available COVID-19 services and data. This week, I’d like to focus on the health equity implications of the PHE’s end.

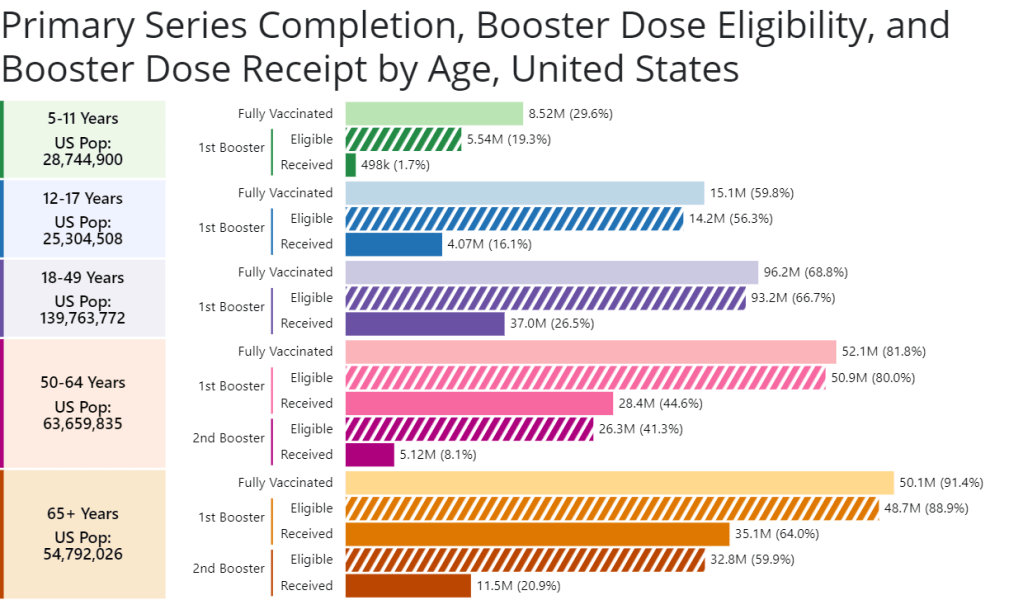

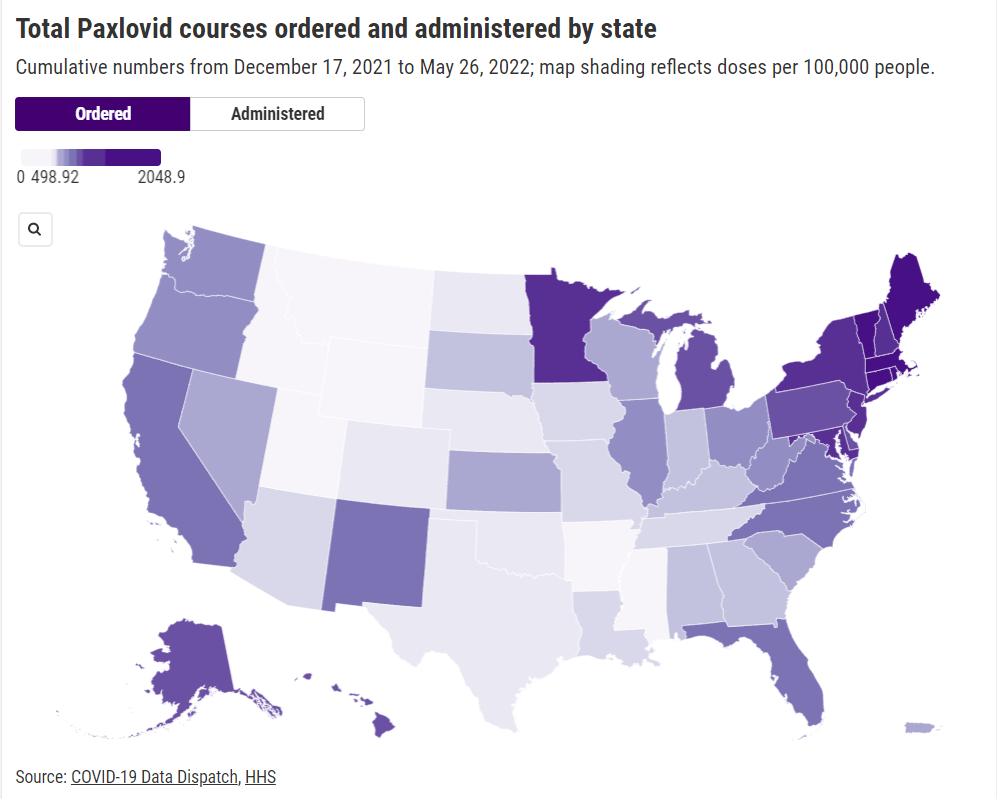

COVID-19 led the U.S. healthcare system to do something unprecedented: make key health services freely available to all Americans. Of course, this only applied to a few specific COVID-related items—vaccines, tests, Paxlovid—and people still had to jump through a lot of hoops to get them. But it’s still a big deal, compared to how fractured our healthcare is for everything else.

The PHE allowed the U.S. to make those COVID-19 services free by giving the federal government authority to buy them in bulk. The federal government also provided funding to help get those vaccines, tests, and treatments to people, through programs like mass vaccination sites and mobile Paxlovid delivery. Through these programs, healthcare and public health workers got the resources to be creative about breaking down access barriers.

Now that the emergency is ending, those extra supplies and resources are going away. COVID-19 is going to be treated like any other disease. And as a result, people who are already vulnerable to other health issues will become more at risk for COVID-19.

I wrote about this health equity problem in a recent story for Amsterdam News, a local paper in New York City that serves the city’s Black community. The story talks about how COVID-19 services in NYC are changing with the end of the PHE, and who will be most impacted by those changes. It’s part of a larger series in the paper covering the PHE’s end.

Most of the story is NYC-specific, but I wanted to share a few paragraphs that I think will resonate more widely:

Jasmin Smith, a former contact tracer who lives in Brooklyn, worries that diminished public resources will contribute to increased COVID-19 spread and make it harder for people with existing health conditions to participate in common activities, like taking the subway or going to the grocery store.

COVID-19 safety measures “make the world more open to people like myself who are COVID-conscious and people who might be immunocomprmised, disabled, chronically ill,” Smith said. “When those things go away, your world becomes smaller and smaller.”

The ending federal public health emergency has also contributed to widespread confusion and anxiety about COVID-19 services, [said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, a professor of epidemiology and global health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health]. “People have so many questions about this transition,” she said, and local leaders could do more to answer these questions for New Yorkers.

The near future of COVID-19 care in the U.S. could reflect existing health disparities for other endemic diseases, like the seasonal flu and HIV/AIDS, [said Steven Thrasher, a professor at Northwestern University and author of the book, The Viral Underclass]. For example, people with insurance and a primary care physician are more likely to get their annual flu shots, he said, while those without are more likely to face severe outcomes from the disease.

After May 11, COVID-19 outcomes are likely to fall along similar lines. “More people have died of AIDS after there were HIV medications,” Thrasher said. “More people have died of COVID when there were vaccines in this country than before.”

For more news and commentary on COVID-19 emergencies ending, I recommend:

- Other stories in Amsterdam News’ The Long Emergency series

- Only the Global-Health Emergency Has Ended (The Atlantic)

- Does the end of Covid emergency declarations mean the pandemic is over? (STAT News)

- End of PHE: A shift in data (Your Local Epidemiologist)

- The Sociological Production of the End of the Pandemic (Death Panel)