By Betsy Ladyzhets

On July 28, 2020, before the start of fall extracurriculars, Andrews Independent School District held a town hall in the high school auditorium. Parents and community members came from across the county to grill the district administrators on their reopening plans. While some parents wanted the details on safety measures, others were more concerned about their individual freedoms.

Bobby Azam, the district superintendent, recalls parents asking questions like, “Are you going to force my child to sit still all day?” or “Are you going to penalize my child if their mask slips off?”

Ultimately, when schools reopened for in-person classes, students in this West Texas district were not penalized for letting a mask slip. The school district prioritized personal responsibility, giving families information to make individual choices about their children’s safety. Partnerships with the local health department, outdoor classes, increased ventilation, and an intensive cleaning regimen also helped keep cases down — even though the district did not follow all Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) protocols, such as required quarantines and masks for the youngest students.

Andrews County’s school district is the subject of the third profile in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series. Alongside four other school communities, we selected it because the majority of the district’s students returned to in-person learning during the 2020-2021 school year — and officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population. (According to the CDC, about 5% of school-aged children in the U.S. have contracted COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.)

Though this district did not adhere to the full extent of COVID-19 prevention guidance, it offers valuable lessons in addressing community politics while still maintaining safety measures — reflecting the challenges that many Sun Belt districts face this fall.

Demographics for Andrews County, Texas

Census population estimates, July 2019

- Population: 19,000

- Race: 56.6% Hispanic/Latino, 39.9% white, 2.0% Black, 1.5% Native American, 1.5% two or more races, 0.7% Asian

- Education: 72.3% have high school degree, 12.2% have bachelor’s degree

- Income: $76,200 is median household income, 10.2% in poverty

- Computer: 91.6% have a computer, 86.2% have broadband internet

- Free lunch: 47.9% of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch1

COVID-19 stats for Andrews Independent School District

Texas Department of State Health Services, Public Schools COVID-19 data

- Total enrollment: 4,000

- In-person enrollment: 82% in late September, 2020; 100%, January through June, 2021

- Total cases, 2020-2021 school year: 167 cases in students, 76 in staff

- Clearfork Elementary School: 6 students, 0 staff

- Underwood Elementary School: 9 students, 0 staff

- Devonian Elementary School: 10 students, 0 staff

- Andrews Education Center: 12 students, 1 staff

- Andrews Middle School: 48 students, 0 staff

- Andrews High School: 68 students, 0 staff

- Unspecified campus: 14 students, 75 staff

1Source: National Center for Education Statistics

Preparing for reopening

When the schools shut down in March 2020, Andrews County was prepared to provide computers for all students. Still, remote learning proved challenging. Many Andrews parents work in the oil industry, which is a major employer in the region, and were unable to work from home — which left many students at home alone.

As a result, when Gov. Greg Abbott announced a plan for fall reopening in June 2020, Andrews district administrators went full speed ahead. Planning for reopening relied on constant communication with the school board and the late July town hall, along with other opportunities for parents to provide feedback.

Administrators also prepared for reopening by intensifying cleaning efforts at Andrews school buildings. The district hired an outside cleaning service to deep clean all buildings, both before the semester began and at regular intervals during the first couple weeks of classes.

All teachers and students in Andrews County had to choose between an all-in-person or all-virtual experience. Unlike other Texas districts, teachers were organized to lead either an entirely virtual or entirely in-person class — no need to teach hybrid classes and split focus between the students in a classroom and the students on Zoom. Meanwhile, students had to commit to in-person class in order to participate in sports or other extracurriculars. In late September, about 82% of students were attending class in person, according to Texas state health department data.

Students who opted for those in-person classes had more outside time than in previous years. Andrews has a warm climate, with temperatures rarely falling below freezing; district staff took advantage by opening windows and doors to outside air, as well as holding class in the playground. Research suggests that outdoor coronavirus transmission is incredibly rare, and ventilation is more effective than cleaning in preventing the spread of aerosols — those tiny virus particles that travel through the air.

“Anytime we could be outside, we did,” Azam said. He found that many students — who were stuck learning from home in spring 2020, while their parents were at work — were especially appreciative of the extra playtime.

Parents’ choice — and parents’ responsibility

Like other districts profiled in this series, the Andrews County school district partnered with the local public health department during its fall reopening. During the fall semester, the public health department shared information about new COVID-19 cases directly with school administrators — notifying the district about a new student case at the same time as the student’s parents. This method went above and beyond guidance from the state of Texas, which stipulated that parents should inform their school district of a case, then the district should inform the public health department. The rapid communication helped the district identify cases quickly and ensure that no cases were missed due to a parent’s reporting hesitancy.

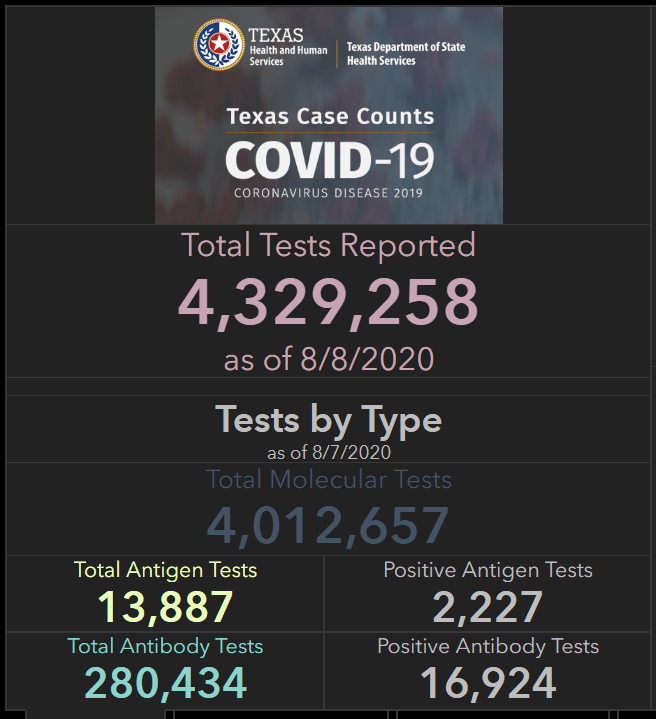

Once a case was identified, the classroom would be immediately cleared and custodians wiped down every surface that the student may have touched. The student’s parents would get a call to pick up their child, and notifications went out to families sharing a classroom with the infected child via ParentSquare, the school’s parent communication service. Those families were all able to access free, drive-through testing right at the local health department — with results in under 24 hours, according to Suzanne Mata, assistant superintendent of student services at the district.

This health department partnership was challenged, however, by “differences of opinion” between district leadership and health workers, as Mata described the relationship. The Andrews school district opted not to require masks beyond the state guidance — which said children under 10 were exempt — and made quarantines optional when a case was identified. The department urged the district to follow CDC guidance: quarantine all exposed students and require masks for all children, including those under age ten.

Rather than relying on strict restrictions, the district “utilized parents,” as Superintendent Azam put it. Parents were able to choose whether a child under age 10 required a mask, while also taking responsibility for other safety measures.

“We said, ‘Mom, Dad, you know your kid better than us,’” Azam said. The district’s quarantine policy reflected this philosophy. While the district required any student with COVID-19 symptoms or a positive test result stay home from school, children who shared a classroom with an infected student had the choice to quarantine or continue coming to class as usual.

“We just said, an individual has been in your student’s classroom… that has actually tested positive — please be aware to look for these symptoms,” Mata said, describing the notification that parents received after a positive case. The notice also reminded parents that any child with symptoms had to stay home.

Gordon Mattimoe, director of the Andrews County Health Department, called the district’s policy “not ideal for mitigation.” After the fall 2020 semester and deterioration of the relationship between district and health department, as Mata described the situation, the health department stopped sharing case information directly with the school district. Instead, parents were asked to report any student cases, further placing the responsibility for COVID-19 mitigation on parents. Administrators felt that parents had sufficient understanding and trust in the district’s protocol to report cases responsibly.

Transitioning to 100% in person

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();

The fall 2020 semester started off smoothly, except for a small outbreak in a sports team. As parents saw the district keep case numbers low — while remaining flexible on safety measures — in-person enrollment grew.

“Every week, we had more and more kids… coming back face to face,” Superintendent Azam said. The students who had opted for the district’s virtual learning option struggled, both with getting assignments turned in and with mental health while home alone.

As a result, the district decided to end the virtual option halfway through the fall semester, phasing students back in throughout October and November. During this transition, some families chose to drop out of the public school district entirely and switch to homeschooling or another option. According to data from the Texas public health department, the district’s total enrollment dropped by 157 students — from 4,149 in October 2020 to 3,992 in January 2021.

In total, the Texas health department reported 167 cases among Andrews students over the course of the school year, representing about 4% of the total student body. They reported 76 cases among staff. The district saw its highest case spikes in November, December, and January, when the country was undergoing its highest surge, followed by almost zero cases between March and the end of the school year in late May. This may be an undercount, however, as the public health department was no longer sharing case data with the district during the spring.

Superintendent Azam acknowledged that luck may have been a factor in Andrews’ low case counts; this rural district was not hit hard by COVID-19 like El Paso and other parts of Texas. The district also likely benefited from improved ventilation, via outdoor classes and open windows. Finally, while parents were expected to report cases to the school and take responsibility for quarantines, administrators say that trust built up throughout the fall semester enabled district parents and staff to become unified around the goal of keeping kids in classrooms and COVID-19 out of classrooms — making this individual responsibility system effective.

The Andrews district has taken away key lessons from the 2020-2021 school year. These include: a continued focus on cleaning when COVID-19 or any other illness is identified in a school building; telling teachers and students to stay home if they feel sick; and holding class outside whenever possible.

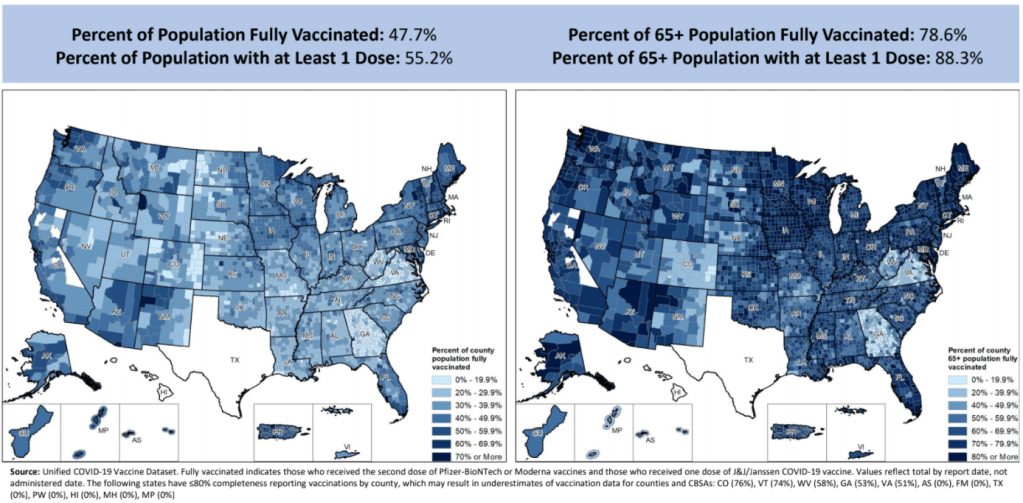

As the Delta variant now sweeps through Texas and Governor Abbott blocks school mask mandates, Mattimoe, from the county health department, is concerned that Andrews’ flexible safety strategy may be harder to maintain this year. The public health department typically partners with the district on fall childhood vaccination events, he said, but opted not to hold events at the middle school this year due to COVID-19 vaccine polarization in the community. About 42% of the county’s eligible population is fully vaccinated as of August 28, according to Texas state data; the state average is 57%.

“With the governor’s orders, the school is going back to business as usual,” Mattimoe said.

Mata, the assistant superintendent, said that the district is “staying very vigilant” and aiming to “do what’s right for our students and our staff.” As of August 22, the district has yet to report any cases in the fall 2021 semester.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge. If you or your outlet is interested in publishing any part of this series, please contact betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

More from the Opening series