- CDC investigating deaths from Long COVID: Researchers at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics are currently working to investigate potential deaths from Long COVID, according to a report from POLITICO. The researchers are reviewing death certificates from 2020 and 2021, looking for causes of death that may indicate a patient died from Long COVID symptoms rather than during the acute stage of the disease. There’s currently no death code associated with Long COVID and diagnoses can be highly variable, so the work is preliminary, but I’m really looking forward to seeing their results.

- CDC reports on ventilation improvements in schools: And one notable CDC study that was published this week: researchers at the agency from COVID-19, occupational health, and other teams analyzed what K-12 public schools are doing to improve their ventilation. The report is based on a survey of 420 public schools in all 50 states and D.C., with results weighted to best represent all schools across the country. While a majority of schools have taken some measures to inspect their HVAC systems or increase ventilation by opening windows, holding activities outside, etc., only 39% of schools surveyed had actually replaced or upgraded their HVAC systems. A lot more work is needed in this area.

- Results from the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy database: The Boston University team behind the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy database has published a paper in BMC Public Health sharing major findings from their work. The database (which I’ve shared in the CDD before) documents what states have done to curb COVID-19 spread and address economic hardship during the pandemic, as well as how states report COVID-19 data. In their new paper, the BU team explains how this database may be used to analyze the impacts of these policy measures on public health.

- Promising news about Moderna’s bivalent vaccine: Moderna, like other vaccine companies, has been working on versions of its COVID-19 vaccine that can protect better against new variants like Omicron. This week, the company announced results (in a press release, as usual) from a trial of a bivalent vaccine, which includes both genetic elements of the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and of Omicron. The bivalent vaccine works much better than Moderna’s original vaccine at protecting against Omicron infection, Moderna said; still, scientists are skeptical about how the vaccine may fare against newer subvariants (BA.2.12.1, BA.4, BA.5).

- Call center and survey from FYLPRO: A reader who works at the Filipino Young Leaders Program (FYLPRO) requested that I share two resources from their organization. First, the program has set up a call center aimed at helping vulnerable community members with their COVID-19 questions. The call center is available on weekdays from 9 A.M. to 5 P.M. Pacific time in both English and Tagalog; while it’s geared towards the Filipino community, anyone can call in. And second, FYLPRO has launched a nationwide survey to study vaccine attitudes among Filipinos; learn more about it here.

Tag: State data

-

Sources and updates, June 12

-

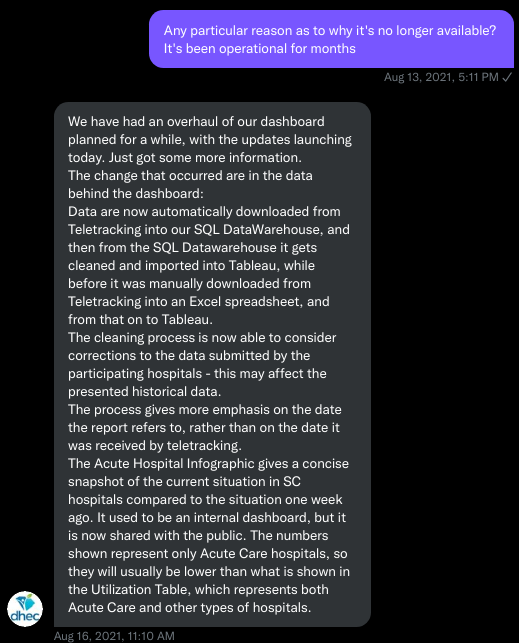

How one wastewater plant became a leading COVID-19 forecasting source

The Metro Plant in the Twin Cities, Minnesota metro area has been tracking COVID-19 in wastewater since 2020. Dashboard screenshot retrieved on April 24. This week, I had a new story published with FiveThirtyEight and the Documenting COVID-19 project about the data and implementation challenges of wastewater surveillance.

COVID-19 levels in waste—or, from our poop—have become an increasingly popular data source in the last couple of months (in this newsletter and for many other reporters and commentators), as PCR testing sites close and at-home tests become the norm. Wastewater can provide us with early warnings of rising transmission, and it includes COVID-19 infections from people who can’t or don’t want to get a PCR test.

But wastewater surveillance is very uneven across the country, as I’ve noted before. A lot of local health agencies, research groups, and utility companies are now trying to expand their COVID-19 monitoring in wastewater, but they face a lot of barriers. My reporting suggests that we are many months (and a lot of federal investment) out from having a national wastewater surveillance system that can actually replace case data as a reliable source for COVID-19 trends and a driver for public health action.

For this story, I surveyed 19 state and local health agencies, as well as scientists who work on wastewater sampling. Here are some major challenges that I heard from them (pulled from an old draft of the story):

- Wastewater surveillance is highly sensitive to changes in a community’s coronavirus transmission levels, particularly when those levels are low, as has been the case across the U.S. in recent weeks.

- Every wastewater collection site is different, with unique environmental and demographic factors – such as weather patterns or popularity with tourists – that must be accounted for.

- While the CDC has led some coordinated efforts through the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS), wastewater sampling techniques overall aren’t standardized across the country, leading to major differences in data quality.

- Sparsely populated, rural communities are particularly challenging to monitor, as their small sizes lead to even more heightened sensitivity in wastewater.

- Wastewater data is hard to communicate, especially when public health officials themselves aren’t sure how to use it. The CDC’s NWSS dashboard is a prime example.

As bonus material in today’s COVID-19 Data Dispatch, I wanted to share one of the interviews I did for the story, which provides a good case study of the benefits and challenges of COVID-19 surveillance in wastewater.

In this interview, I talked to Steve Balogh, a research scientist at the Metropolitan Council, a local agency in the Twin Cities, Minnesota metro area that manages the public water utility (along with public transportation and other services). Balogh and his colleagues started monitoring Twin Cities’ wastewater for COVID-19 in 2020, working with a research lab at the University of Minnesota.

Balogh gave me a detailed description of his team’s process for analyzing wastewater samples. Our conversation also touches on the learning curve that it takes to set up this surveillance, the differences between monitoring in urban and rural areas, and the dynamics at play when a wastewater plant suddenly becomes an important source for public health information. Later in the interview, Bonnie Kollodge, public relations manager at the Metropolitan Council, chimed in later to discuss the wastewater data’s media reception.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. Also, it’s worth noting that the interview was conducted in early April; since then, COVID-19 levels have started rising again in the Twin Cities metro area’s wastewater.

Betsy Ladyzhets: The first thing I wanted to ask about was, the backstory of sampling at the Metro Plant. I saw the dashboard goes back to November 2020, and I was wondering if that’s when you got started, and how that happened?

Steve Balogh: We actually started looking into it in April of 2020. And we contracted with Biobot at that time… But in May, their price went up, so we started looking for alternatives. Then, we started a partnership with people at the University of Minnesota Genomics Center, who know about measuring RNA in things.

At that point, we tried to figure out how to extract the RNA from our samples. They [University of Minnesota researchers] didn’t know anything about wastewater, but they knew everything about RNA. We know all about wastewater, but we don’t know anything about RNA. So it was a good match.

That summer, [the university researchers] started trying to do the extractions and it didn’t really work out so well… So we said, “Okay, we’re going to try this.” By September of 2020, we had built our own lab, and we were trying out our own extractions, based on what we were seeing in the literature, and all the preprints that were piling up. In October, basically we settled on [a sampling process] that worked. And by November 1, we were actually getting data.

BL: Yeah, that definitely aligns with what I’ve heard from some of the other scientists I’ve talked to who have worked on this, where it’s like, everybody was figuring [wastewater sampling methods] out on their own back in 2020.

SB: Yeah, it was on the fly. Papers were coming out daily, just about, with new ideas on how to do things. And we had, like, four different extraction methods that we wanted to look at, also looking at sludge, in addition to influent wastewater… Honestly, it was pretty much pure luck that we settled on [a method] that really, really worked.

We tried to get daily samples, and to put up numbers and see what [the data] looked like. And it actually did work—it actually tracked the reported caseload quite well. We figured, well, it must be working. We also did QA [quality assurance] in the lab, spiking the samples with known amounts of RNA, and trying to get that back. And all of that came back really well, too. So, we have a lot of confidence in our method.

BL: So that [QA] is like, you put in certain RNA, and then you check to make sure that it shows up in the sample?

SB: Exactly, yeah.

BL: What is your process for analyzing the samples and distinguishing those trends, like seeing how they match the case numbers?

SB: We do the extractions at our lab, with the samples from the Metro Plant. We take three milliliters of wastewater and we add 1.5 milliliters of something called Zymo DNA/RNA Shield, from a company in California called Zymo. That’s a buffer that stabilizes the RNA—it basically explodes whatever virus particles are in there, breaks them up, and then it stabilizes the RNA in the sample. So you can actually store those samples at room temperature for days, or maybe even weeks, because the RNA is stabilized.

Then, we put that treated sample through a two-step extraction process. The first step is, we put the whole thing into a Zymo III-P column, combined with 12 milliliters of pure ethanol, and run that through the column. This is a silica column, so the RNA in the sample binds to the silica. Then we wash it and elute that RNA in 200 microliters of water. And then we take that 200 microliters, and run it though the second stage, which is just a smaller silica column. The RNA that’s in that 200 microliters binds onto the smaller column, and then we wash it and elute that into 20 microliters.

Our total concentration is going from three milliliters of wastewater down to 20 microliters of pure water. That’s a concentration factor of 150. We figured that would work for pretty much most situations, and it’s turned out to be true.

Then, we store those samples at minus 80 degrees Celsius. Until we take them over weekly to the University of Minnesota, where they do droplet digital PCR, RT-PCR, to amplify and detect the RNA that’s in our samples. We started out just getting the total viral load back in November 2020. But then, in the early part of 2021 when Alpha showed up, we started doing variant analysis as well. We’re now also looking for specific mutations that distinguish the different variants of concern, like Alpha and Delta and Omicron.

BL: So, you take the samples every day, but then you bring them over [to the university] once a week, is that correct?

SB: That’s correct.

BL: When you’re getting that data, coming from the U of MN lab, what are you doing to interpret it? Or, in communicating the data on your dashboard, what are the considerations there?

SB: We work up the numbers and calculate a total load of the virus, or the particular variants, that’s coming into the plant. And then we basically put that up on the dashboard. There’s not a whole lot of interpretation or manipulation of the data—we’re simply importing the load, basically, of what we see coming into the plant. The load is the concentration that we’ve measured in the sample, times the total volume of wastewater coming into the plant.

We think that’s a sufficient normalization procedure for a large wastewater treatment plant. I know some groups are using other normalization techniques, but we think load is sufficient to tell us what’s happening out in our sewer shed.

BL: Yeah, that makes sense. I know this gets more complicated when you have smaller sites, but your sewer shed is serving a big population—

SB: Almost two million people. Yeah, it’s a big sewershed. If you had 50% of your population leaving during the day to go to work in the next community, that would be something that you might have to consider using other normalization techniques. But that just isn’t the case [in the Twin Cities]. We see a pretty steady signal here.

BL: Makes sense. Have you considered expanding to other sites? Or are is the plan to just stick with sampling at the main sewer ship location?

SB: We already have, actually. We operate nine different wastewater treatment plants in the seven-county metro area. And we’ve already expanded to three of those other sites, so we now have four total plants that we’re taking samples at and having them analyzed at the Genomic Center. It only started within the last month, so we don’t have quite the database to really start showing it on our dashboard yet. But when we do [have more data], our plan is to put that up [on the dashboard] as well.

BL: Do you have a sense of how much time it might take before you feel the data is useful enough to put on the dashboard?

SB: Part of the problem has been, all of these samples that we’re getting from these other plants, we’re just taking the entire sample over to the Genomics Center, and they’re doing the extractions. They’re using my extraction procedure, but they’re doing it in their lab. So, there was some learning curve for them to figure that out. And also to hire staff and come up to speed in terms of facility, and procedure, and people… Now, it’s been a few weeks, and I think they’re just about there [in getting a handle on the RNA extraction methods]. So, I think our data will start to shape up pretty quickly.

Another thing that may be keeping us, at this point, from showing the data is, nothing’s happening. We’re at this bottom [with low coronavirus levels in the wastewater] where everything just looks noisy, because nothing’s changing. But as soon as we start to go up, and if we get higher—the current position is just going to look like a flat line. But right now, people could look at it and say, “Well, that’s just junk.”

So, in that sense, we just don’t want to confuse matters and say, “Here’s a bunch of junk for you to look at. We want to put it into some context. And the context really is, when things start taking off, then you see, “Oh, it used to be very low. And now it’s very high.”

(Editor’s note: Since this interview was conducted in early April, COVID-19 levels have started rising in the Twin Cities metro area.)

BL: That makes a lot of sense. Also, I hear you on the challenges of learning these methods. I was a biology major in school, and I worked in a lab, briefly, that did RNA extraction. And I remember how tricky it is, so I can envision the learning curve.

SB: Well, these are experts at the Genomics Center, they know what they’re doing. But I think even they have been surprised at how how robust the viral RNA is in wastewater. A lot of people at the beginning of this pandemic said, “You’ll never see it in wastewater. It’s RNA, RNA is very sensitive, it’ll break down.” But that just isn’t the case—the RNA is quite robust in wastewater, and the signal lasts for a long time. It has to last for many hours, for it to travel from the far end of our sewershed to get to us [at the treatment plant]. And then, even in the refrigerator, when you refrigerate just the raw sample, it’ll stay in a reasonable concentration without dropping too much for days.

BL: What has the reception to this work been from the public, the state health department, or from local media or other people who are using and watching the data?

SB: It’s been incredible. You can ask Bonnie more about it.

Bonnie Kollodge: It’s ginormous. I mean, it just has spread everywhere. I don’t even know the social spread, but I think somebody was tracking our impressions in print and online media… I think there were, like, 11 million impressions between January and the end of March. And we get lots of requests for Steve’s time, lots of requests for a daily accounting [of the data].

When we began this work, it really was out of public service—seeing that there’s a pandemic going on, and what can we do to help? That’s when they started developing this idea, then working with the Depratment of Health, which is really our state lead on this [COVID-19 response]. They came to rely heavily on our information, to compare it against what their test results were showing. Then, as people started to do home testing, that was a whole other factor. It was really wastewater that was taking the lead on showing what was happening with the virus and the variants…

Every week, we put an update online, and reporters go right to it, to determine how they’re gonna position [their COVID-19 updates]. Steve also provides, in addition to the data, a little narrative about what’s happening that helps reporters—some who are very conversant in data, but others who are not—it helps them it understand what we’re seeing.

BL: I can see how that would be helpful, especially if you’re releasing a week’s worth of data points at once. You sort-of have a mini trend to talk about.

BK: Yeah, and we send it to the governor’s office, and to the Health Department. They appreciate the transparency… They know what’s happening [with the virus], and can adapt.

BL: Right. And Bonnie, you mentioned something I wanted to ask more about, which is how the increased use of at-home tests and lower availability of PCR tests has increased the demand for wastewater data in the last few months, in particular. Now that you maybe have less reliable case data to compare against, has the thinking and interpreting the wastewater data shifted at all?

SB: I think we’ve actually had that statement from reporters. They’ve said, “We can’t trust the testing data anymore. And it’s going to be wastewater from here on out.”

BK: Just this week, there was a reporter who asked to get early results tomorrow. And he said, “This [wastewater data] is what I’m watching.” … The public has glommed on to this resource as a demonstration of what’s happening. And, like Steve said, it’s not a small sample. There are almost two million people served by this by this particular plant.

BL: From what I understand, part of what can be really helpful [with wastewater data] is when you have that longevity of data, as you all do. You have a year and a half of trends. And so when you see a new spike, it’s easier to compare to past numbers than for other parts of the country that are just starting their wastewater surveillance right now.

SB: Yeah. I think the other thing that has been really useful for our [state] department of health is, they’ve really appreciated the variant data that we have. That was really the first thing that got their attention… And we were giving them [variant] data ahead of time. The clinical tests were taking days or weeks to come back, and we could give them variant data the same week. So, that was the first thing that got our department of health here interested. But when they saw that we can track trends, they recognized that this has value at lower levels when testing goes away, basically.

BL: How would you want to see support from the federal government in expanding this wastewater work? Like you mentioned, getting it in more treatment plants, and any other resources that you feel would be helpful.

SB: Well, I think that’s underway, as we understand it, with the National Wastewater Surveillance System, NWSS. I think they’re funded through 2025, and I think the goal there is to basically sign up as many treatment plants as they can in the country.

(Editor’s note: This is accurate, per a CDC media briefing in February.)

Hopefully, that’s the beginning of something that is going to go beyond the pandemic, and give us a measure of community health in the future. Because wastewater is a community urine test, basically. It’s everybody contributing, and it can be useful for other pathogens and viruses in the future. So, yeah, [expanding that network] would be great. Let’s do it.

BL: Do you envision adding other viruses to the testing that you’re doing? Flu or RSV are ones that I’ve heard some folks are considering.

SB: Yeah, that would be something to do going forward for us. Though, it’s not clear how long we continue this work, just because these other projects are expanding, like the national project. And even our department of health here [in Minnesota] is talking about bringing this type of analysis into their own laboratory. Certainly going forward, long-term, that would be a goal for any work done here in Minnesota—to add those things to the menu of what we’re analyzing.

BL: Right. So you might be taking the samples to the Minnesota health department instead of the university, or something like that?

SB: Someday. Yeah, we just don’t know at this point.

BK: This is an evolving scinece. And this is not what we typically do—I mean, we do wastewater collection and treatment. So this [COVID-19 reporting] is a little outside of our regular parameters. But, like Steve and his superiors have been saying, this is an evolving science, so let’s see where this takes us, in terms of infectious disease.

It’s funny, when I go out and talk to people and say, “I work for the Met Council, and I help in communications with the wastewater analysis,” everybody knows what I’m talking about. It’s just so much out there. But I think that these things [testing for other diseases] are all being explored, and this has really opened up new possibilities.

SB: From the beginning, it’s just been a scramble. You don’t know what’s going to be coming. What I’m doing, a lot, is trying to get ourselves in a position so that, when the next variant of concern pops up, we have an assay that can measure it. There’s still a lot of unknowns about what’s going on, and everything’s new every day, just about.

More state data

-

Idaho’s hospitals as a case study of decentralized healthcare

In last week’s issue, I mentioned that I am thinking more about preparedness: how the U.S. can improve our capacity to respond to public health threats, future COVID-19 surges and beyond. This mindset shift was brought on, in part, by a recent story I worked on at the Documenting COVID-19 project: examining the vulnerabilities in Idaho’s hospitals as a case study of the U.S.’s decentralized healthcare system.

Last summer and fall, Idaho was completely overrun by the Delta variant. State leaders implemented crisis standards of care, a practice allowing hospitals to conserve their limited resources when they are becoming overwhelmed. All hospitals in Idaho were in crisis standards for weeks, with the northern Panhandle region remaining in this crisis mode for over 100 days.

During this time, Idaho hospitals sent out 6,300 patient transfers in the span of four months. With Audrey Dutton, my reporting partner at the Idaho Capital Sun (a nonprofit newsroom covering Idaho state government), I analyzed data from the Idaho health department that showed where these patients were transferred, as well as how the crisis period compared to previous months.

This map shows all patient transfers out of Idaho hospitals between April and November 2021. Chart by Betsy Ladyzhets, published in the Idaho Capital Sun and MuckRock. Here are the major findings from our story (borrowing some text from my Twitter thread, linked above):

- More than one in three transfers went to hospitals in neighboring states, with the highest numbers going to eastern Washington.

- Transfers went as far as Seattle, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Billings, and even Phoenix. Many of these trips required air ambulances, due to Idaho’s mountainous geography.

- These transfers strained Washington hospitals. Dr. Dave Chen, chief medical officer at MultiCare Deaconess Hospital in Spokane—one Washington hospital that took on a lot of Idaho patients—told me that smaller, rural facilities in his area are all “competing for the same beds and resources,” whether these facilities are based in Washington or Idaho.

- Workers at facilities in the northern Idaho region, which remained in crisis standards for over 100 days, described doubling patients up in ambulances, traveling for hours to find free beds, and taking EMS staff away from their normal duties for long trips.

- Idaho is particularly vulnerable to transfer challenges: it has a lot of small rural hospitals without many ICU beds or specialized equipment, combined with geography that often requires an air ambulance rather than driving.

This story has implications beyond Idaho, as it shows the impact of America’s fractured health system. In our system, when hospitals in one state are in crisis, they cannot easily communicate with other hospitals that might be able to help them out—whether “communicating” means calling up hospital administrators to ask about free beds or sharing data about patient numbers and resources.

This is not just a COVID-19 problem. Consider what happens when a wildfire, hurricane, or other natural disaster hits. When hospitals in one area become overwhelmed, they should be able to easily reach out to other facilities—but our system makes this incredibly difficult.

One potential solution to this issue may be centralized transfer centers, which field calls from hospitals that need to send out their patients. Washington started such a transfer center during the pandemic, to great success: Dr. Steve Mitchell, who helps run the center, told me that it facilitated more than 3,500 patient transfers, mostly between summer 2021 and early 2022.

But there’s a kicker: Washington’s transfer center is funded by the state health department, and therefore it can only answer calls from Washington hospitals. If an Idaho hospital wants to transfer a patient into Washington, it has to call various Washington hospitals directly until finding a bed for that patient—a much more time- and resource-intensive process.

Look at how siloed our current system is! This is ridiculous! Clearly, we need transfer centers with regional—or even national—reach, coordinated by a national health agency. We also need more data sharing between hospitals, and better communication between facilities and EMS providers.

Again, you can read the full Idaho story here, and check out my underlying data analysis here.

-

Contracted staffing issues in Missouri reveal broader crisis in hospitals

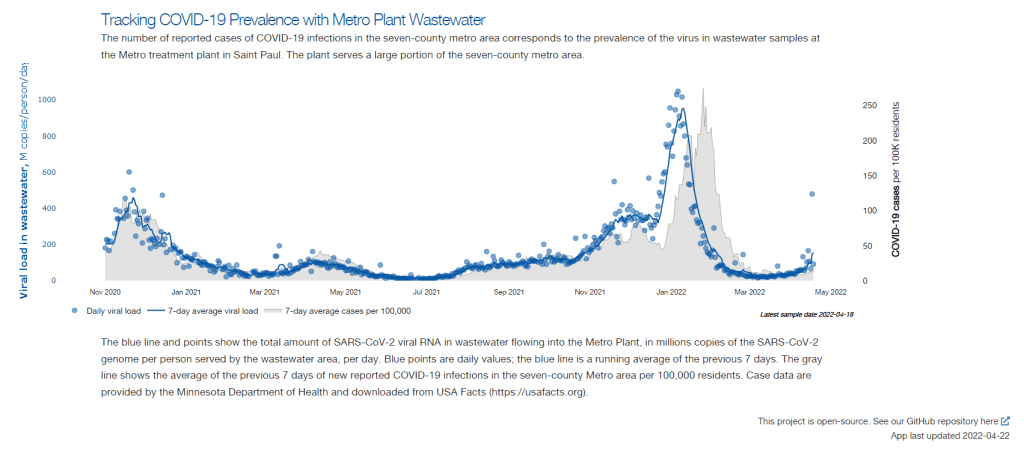

Chart from the Missouri Independent story. Early this week, I had a big story published in The Missouri Independent, as part of the Documenting COVID-19 project’s ongoing collaboration with that nonprofit newsroom. This piece goes in-depth on the Missouri health department’s contract with SLSCO, a Texas-based construction company that expanded to provide healthcare support during the pandemic.

While this was a local story, to me, the piece provides important insights about the type of support that is actually needed in U.S. hospitals right now: not temporary assistance, but long-term, structural change.

The Missouri agency hired SLSCO to provide two services, with a total contract of $30 million:

- Provide staffing support (nurses, technicians, etc.) to hospitals across the state struggling in the wake of the Delta surge.

- Set up, staff, and operate six monoclonal antibody infusion sites where Missourians infected with the coronavirus could easily access the treatment.

SLSCO made lofty promises to the Missouri health department, citing its ability to quickly send hundreds of workers to facilities that required assistance. But in fact, the hospital staffing assistance was marred by delays, no-shows, and high rates.

Here are a few paragraphs from the story:

Fewer hospitals signed on to receive staff than the Department of Health and Senior Services anticipated. Within the first few weeks, some hospitals faced no-shows, while the company’s hourly rates — up to $215 an hour for some nurses and $550 an hour for doctors — were too high for other hospitals to afford after state funds ran out, according to emails obtained by The Independent and the Documenting COVID-19 project through records requests. (Copies of SLS’ contract and emails between state agencies can be found here.)

“153 staff requested and only 10 deployed,” wrote Alex Tuttle, the governor’s legislative budget director, after receiving a staffing report early in the contract period. “Am I reading that right?”

From mid-August through November, just 206 staff were ultimately sent to 53 hospitals, said Lisa Cox, a spokeswoman for DHSS. The healthcare support had left by the time omicron hit in the winter.

The monoclonal antibody infusion sites were more successful; in fact, the Missouri health department ended up redirecting funding from the staffing support to the infusion sites. The six sites served a total of 3,688 patients over a two-month period.

However, the sites could have served a lot more patients: these clinics could have treated up to 136 patients each day but peaked at about 90, with numbers often much lower, according to my analysis of data from the health department. Due to these low numbers, the state of Missouri ended up spending more than $5,600 for each patient. One monoclonal antibody expert I talked to for the piece called this an “exorbitant” cost.

Now, I don’t mean to hate on monoclonal antibody treatments here—these drugs are truly a great way to boost the immune systems of COVID-19 patients who may be at higher risk for severe symptoms. Maggie Schaffer, a case management nurse who helped set up one of the infusion sites, told me that people who had this treatment typically are “feeling like a whole new person” within a day or two.

However, the treatments are very expensive and inefficient; one patient’s infusion appointment can take hours. The drugs themselves cost around $2,100 per dose, about 100 times as much as one vaccine. Health departments and facilities that offer monoclonal antibodies need to focus on getting the word out to patients so that these expensive supplies aren’t wasted.

At the same time, temporary healthcare staff can be great to help a facility out a surge—but they are not a long-term solution. In particular, nurses at a hospital may be frustrated by watching new staff come in from out of town and receive much higher pay rates; the “traveling nurse phenomenon,” as this is called, may contribute to burnout and staff leaving to go become traveling workers themselves.

What do hospitals actually need to do to address their staffing crisis? Here are a few ideas from Tener Veenema, a nursing expert focused on health systems a professor of nursing who researches health systems and emergency preparedness at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health:

- Higher pay and assistance with education bills.

- Regulations on things like work hours, the number of patients one nurse can be responsible for at once.

- Mental health assistance that nurses are actually given time and space to access.

I’ll end the post with this quote from Veenema, which is also the last line of the story:

“If we don’t fix the toxic work environment, this issue of mandatory overtime, inadequate staffing levels, lack of time to access mental health resources,” Veenema said, “then you’re simply shooting more new nurses out of the cannon, but into the lake where they’re going to drown.”

-

States treating COVID-19 as “endemic” is leading to shifts in data collection and reporting

Screenshot from the California SMARTER plan. This week, California became the first state to officially shift to an endemic strategy for dealing with COVID-19. Last week, I discussed the recent trend in states ending mask requirements in public schools, businesses, and other settings, by providing readers with some suggestions for encouraging safety during this push to “open everything” (that wasn’t already open). This week, more states are dropping safety measures; for example, Washington governor Jay Inslee announced that the state’s indoor mask mandate will end on March 21, though this change is also contingent on a low level of COVID-19 hospital admissions.

At the same time, some states are also making major shifts in the ways they collect and report COVID-19 data. State public health departments are essentially moving to monitor COVID-19 more like the way they monitor the flu: as a disease that can pose a serious public health threat and deserves some attention, but does not entirely dictate how people live their lives.

You may have seen this shift discussed as a movement to treat COVID-19 as “endemic.” An endemic disease, from an epidemiologist’s standpoint, is one that’s controlled at an acceptable level—it hasn’t been completely eradicated, but the levels of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are generally deemed as levels that can continue without major public health measures. For more on the topic, I recommend this post from epidemiologist Ellie Murray (whom I’ve quoted on this topic before).

We can argue—and many COVID-19 experts on Twitter are arguing—about whether this is the appropriate time to shift into endemic mode. Still, regardless of individual opinions, state public health departments are starting to make this shift, and I think it’s worthwhile to discuss how they’re doing it, particularly when it comes to data.

Here’s a brief roundup of four states that are shifting their COVID-19 data collection and reporting.

California

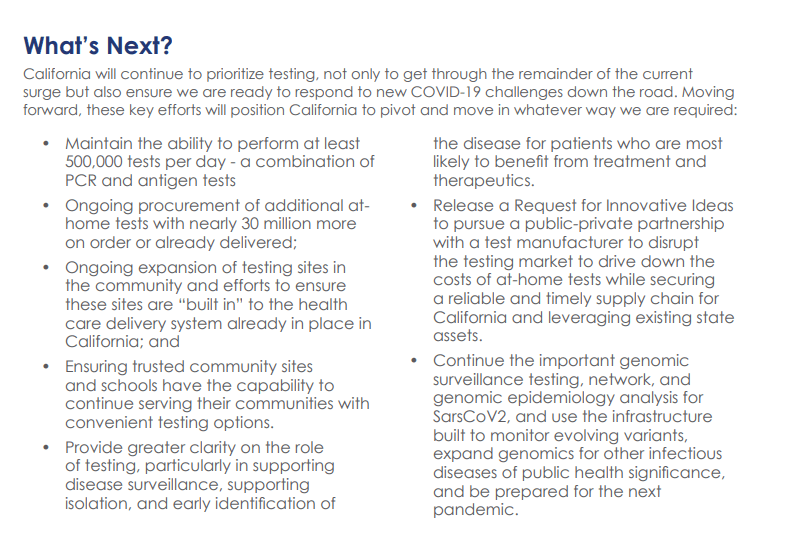

California made headlines this week for being the first state to officially shift into “endemic” policy for dealing with COVID-19. State officials have drafted a plan called “SMARTER”—which stands for Shots, Masks, Awareness, Readiness, Testing, Education, and Rx (treatment). I took a look at the plan, which reporters from NBC Bay Area kindly shared publicly on DocumentCloud.

Here are a few data-related highlights:

- State officials will “focus on hospital numbers” to gauge how California should react to potential new variants that may be more infectious or more capable of causing severe disease.

- Unlike some other states, California is maintaining testing capacity going forward, including an expansion of community testing sites and ongoing procurement of at-home antigen tests for public schools, long-term care facilities, and other institutions.

- Throughout the pandemic, California has invested in genomic sequencing for COVID-19 cases, as well as a statewide modeling tool that compiles several different forecasts. These surveillance tools will be further expanded to respond to COVID-19 and other infectious disease outbreaks.

- California also intends to “build a robust, regionally based wastewater surveillance and genome sequencing network” that can provide early warnings about new outbreaks.

- The plan includes a focus on equity: California leaders will monitor testing, cases, and other metrics in minority communities so that resources can be provided to address disparities if needed.

Missouri

Missouri started its shift to “endemic” in December, as the governor declared an end to the state’s public health emergency around COVID-19—even though cases were at their highest-ever level in the state. Now, the Missouri health department is preparing to change its data reporting accordingly, my colleague Derek Kravitz and I reported in the Missouri Independent this week. (The Independent, a nonprofit newsroom focused on Missouri’s state government, is a long-time collaborator of the Documenting COVID-19 project, where I work part-time.)

Here are the planned data changes highlighted in our story:

Case investigations and contact tracing, where local health departments’ staffers reach out to people exposed to the virus in workplace or other public settings, will cease, unless a new, more transmissive or deadly variant emerges;

Daily reports on COVID-19 cases and deaths by the state health department will be replaced by aggregate weekly reports. In some cases, metro health departments, including those in St. Louis and Springfield, will likely continue collecting and disseminating daily reports but the state will stop its reporting;

Positivity rates will be phased out, as they are already difficult to interpret, with many Americans having switched from PCR tests to at-home antigen tests. Most people don’t report their results to local health departments. Missouri officials in January said they were prepared to be a “trend setter” in eliminating positivity rate reporting.

Hospitalization data will become even more important, with state health officials hoping to make reporting more timely;

Wastewater surveillance will become a more relied-on data point for public health officials, as a way to spot COVID-19 early in its life cycle and identify potential hot spots. Missouri is a leader in wastewater surveillance, as the state has the highest number of collection sites reported on a new CDC dashboard.

Iowa

A couple of weeks ago, I called out the state of Iowa for decommissioning its two COVID-19 dashboards, one dedicated to vaccination data and one for other major metrics. (I’m still bummed out about this, to be honest! Iowa had one of my favorite/most chaotic dashboards to check as a COVID Tracking Project data entry volunteer.)

The change actually occurred this week: the old link to Iowa’s vaccination dashboard now goes to a 404 page, and all Iowa COVID-19 data are now consolidated in a single “COVID-19 reporting” page on the overall Iowa health department website.

Here’s a bit more information on Iowa’s data shift, from a press release by the state’s governor:

- Rather than reporting daily COVID-19 case numbers, vaccinations, and other data, Iowa is now providing weekly updates. The new, pared-down dashboard includes positive tests and death numbers over time, case and vaccination rates by county, and some demographic data.

- For more frequent COVID-19 reporting, the Iowa dashboard now directs residents to federal data sources. Iowa is still reporting daily to the federal government, as all states are required to do.

- The state health department “will continue to review and analyze COVID-19 and other public health data daily,” Governor Kim Reynolds said. But some teams focused on the COVID-19 response will return to pre-pandemic responsibilities.

- This reporting change is intended to align with “existing reporting standards for other respiratory viruses,” Gov. Reynolds said.

- Iowa is focusing on at-home tests with a program called “Test Iowa at Home,” in which residents can request to have a test kit sent to their homes for free. (It was unclear to me, from browsing the website, whether these are rapid antigen tests or PCR tests.) The state health department processes these tests and collects data from the program.

South Carolina

A Tweet from South Carolina data expert Philip Nelson alerted me to this one: not only is South Carolina shifting from daily to weekly data reports, the state is essentially ending all reporting of COVID-19 cases. This is paired with a gradual shutdown of testing sites in the state.

Here’s more info on South Carolina’s shift, based on a press release from the state health department:

- South Carolina’s health department will stop reporting daily COVID-19 case counts on March 15.

- The agency will continue to report COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths as important indicators of disease severity, but these will switch to a weekly update schedule rather than daily.

- The shift away from case reporting aligns with a greater focus on rapid at-home tests, which South Carolina’s health department says are “not reportable.” (While it’s true that the vast majority of rapid at-home test results are not reported, some jurisdictions, like D.C., allow residents to self-report their results!)

- South Carolina’s health department is planning to gradually shut down almost all public PCR testing sites in the state throughout the month of March. According to the department, these sites have seen “a significant decrease in demand” due to increased availability for rapid tests.

- The department is also discouraging regular testing for asymptomatic South Carolina residents, saying that individuals who are currently symptomatic or have a close contact who tested positive should be prioritized.

More news on this topic

- The CDC continues adding wastewater collection sites to its new dashboard. Two weeks ago, I wrote that only ten states had ten or more sites included on the dashboard; since then, three additional states have crossed that threshold: Illinois, Washington, and West Virginia. But the dashboard is still empty for the majority of states, indicating a lack of this important surveillance tool in much of the country.

- For an upcoming story, I recently interviewed Lauren Ancel Meyers, a modeling expert at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author on this fascinating paper about using hospital admissions and mobility data for pandemic surveillance. Meyers has considered cases to be a messy indicator throughout the pandemic, she told me. She finds hospital admissions to be more useful, as this metric will directly show how many people are seeking healthcare due to their COVID-19 symptoms.

- Another interesting paper, published in Nature this week, describes the use of machine learning models to drive COVID-19 testing at a university. The models could “predict which students were at elevated risk and should be tested,” the researchers write; students tested because of the models tended to be tested more quickly and were more likely to test positive than those identified through manual contact tracing or general surveillance. Such modeling could be used to augment the type of random sampling that Natalie Dean described in a recent article, shared in last week’s issue.

Are there any other states shifting their data reporting for an endemic COVID-19 state that I’ve missed? Email me or comment below and let me know!

More on state data

-

COVID source callout: Iowa ends COVID-19 dashboards

On February 16, Iowa’s two COVID-19 dashboards—one dedicated to vaccination data, and one for other major metrics—will be decommissioned. The end of these dashboards follows the end of Iowa’s public health emergency declaration, on February 15.

In a statement announcing the end of the public health emergency, Iowa Governor Kim Reynold assures residents that “the state health department will continue to review and analyze COVID-19 and other public health data daily.” Data reporting on COVID-19 will be more closely aligned to reporting on the flu and other respiratory diseases, she said. Even though COVID-19 is causing the death of more than 100 Iowa residents a week, according to CDC data.

Iowa used to be the state with the most frequent COVID-19 data reporting, with a dashboard that updated multiple times an hour. In fact, I wrote an ode to its frequent updates here at the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, back in fall 2020. But now, Iowa joins Florida, Nebraska, and other states in ending its public health emergency and, consequently, severely downgrading the level of information that it’s providing to residents who are very much still living in a public health emergency.

At least the state will continue providing regular updates to the CDC—those requirements haven’t changed.

-

Cash incentives for vaccination have little impact

Over the past year, vaccine incentives have become a popular strategy among businesses and state and local governments. From free donuts to free Mets tickets, Americans have had opportunities to get bonus rewards along with protection from the coronavirus. And one particularly common incentive is cash, offered through small payments accompanying vaccinations and lotteries that only vaccinated people can enter.

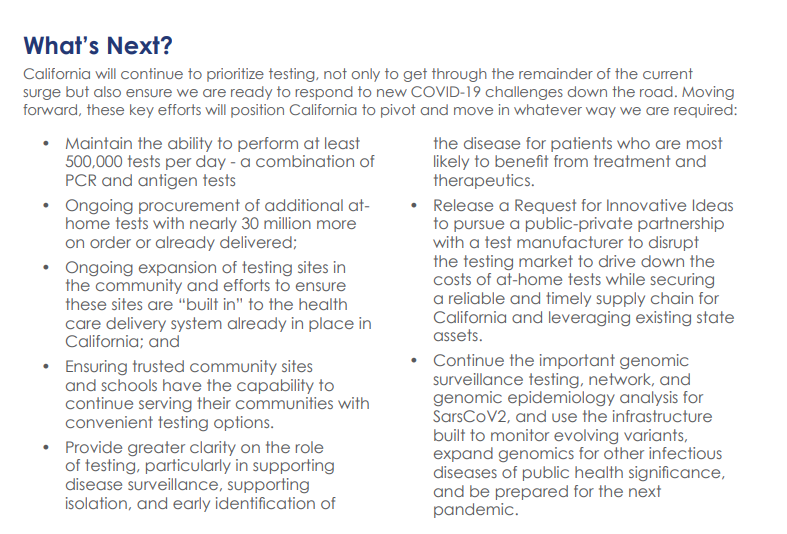

While politicians at all levels have praised cash incentives, research has shown that this strategy has little impact on actually convincing Americans to get vaccinated. A recent investigation I worked on (at the Documenting COVID-19 project and the Missouri Independent) provides new evidence for this trend: the state of Missouri allocated $11 million for gift cards that residents could get upon receiving their first or second vaccine dose, but the vast majority of local health departments opted not to participate in the program—and a very small number of gift cards have been distributed thus far.

The Missouri program’s limited success fits into a national pattern. “It’s hard to tease out a causal effect of a program that’s not introduced with the purpose of a research experiment,” Dr. Allan Walkey, an epidemiologist at Boston University who’s studied vaccine incentives, told me. Still, Walkey said, the majority of research on these programs has found that cash incentives are not driving huge numbers of people to get their shots.

Walkey specifically studied a vaccine lottery in Ohio, the first state to set up such a program. While initial reports by state leaders suggested that a lot of people got vaccinated after the lottery was announced, Walkey found that, in fact, the new vaccinations were more likely caused by an expansion of vaccine eligibility. Two days before the lottery was announced, the Pfizer vaccine was authorized for children between the ages of 12 and 15.

The lottery “didn’t have a large effect on vaccine uptake,” Walkey told me. Studies of vaccine lotteries in other states have found similar results.

For this story, I also spoke to Ashley Kirzinger, a polling expert at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) who helps run KFF’s Vaccine Monitor surveys. In these surveys, KFF sorts unvaccinated Americans into categories based on their vaccine attitudes: “wait and see,” “only if required,” and “definitely not.” Kirzinger told me that cash incentives, vaccine requirements for events, and other social pressures are more likely to “motivate the ‘wait and see’ or ‘only if required’” groups.

But for those Americans who “definitely” don’t want to get vaccinated, these incentives aren’t likely to move the needle. In fact, the people in this group may be angered by incentives, because they could see such programs as unfair pressure from the health system.

This was true in some Missouri local public health departments. For example, in Carter County—where the local agency did opt in to the state gift card program—a planned vaccination drive with the gift cards was canceled due to local opposition.

“So many parents and community members were upset, we were not allowed to hold the vaccination event at the school,” said Michelle Walker, the county health center administrator.

Overall, out of 115 local public health agencies in Missouri that were eligible to participate in the incentive program, just 20 opted to get gift cards. Most departments purchased $50 gift cards, so that residents could get $50 at their first vaccine dose and $50 at their second dose.

Through surveying the local agencies that participated, my colleague Tessa Weinberg and I obtained data from 10. Out of 6,378 gift cards that the agencies were able to purchase with state funding, we found that just 1,712 had been distributed so far, as of late November.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();Read the full story for more on why many departments didn’t participate in this gift card program, and how it’s going for the departments that did opt in.

-

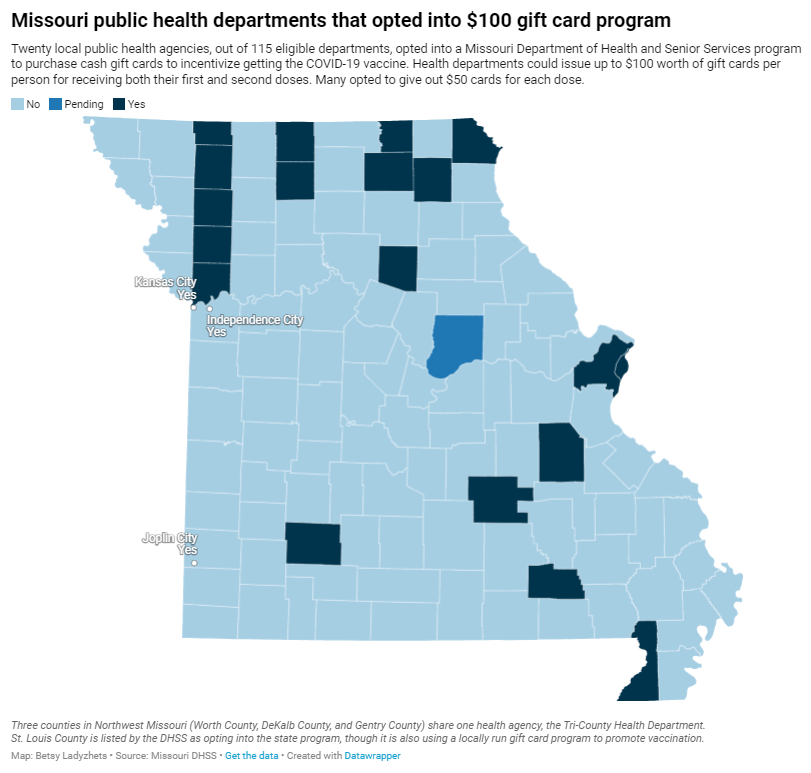

COVID source callout: Vaccination rates by Zodiac sign

In last week’s newsletter, I gave a shout-out to the Salt Lake County Health Department, which posted this novel vaccination data on Twitter:

The post drew a lot of attention in the COVID-19 data world, including with readers of the COVID-19 Data Dispatch. (Shout-out to the reader who sent me some bonus analysis of vaccinations by Zodiac element!) Unfortunately, additional research into the Salt Lake County Health Department’s data has shown me that the agency’s analysis might not be particularly robust—and I feel it is my journalistic duty to share this with you.

Here’s the deal. In order to calculate vaccination rates by Zodiac sign, you need two things: vaccinations organized by birthday (your numerator), and the overall population organized by birthday (your denominator). Health departments can easily access the numerator, as it is standard for people to provide their birthdays along with other basic demographic information when they get vaccinated.

But the denominator is trickier. The average U.S. public health department doesn’t have access to the birthdays of every resident in its jurisdiction; some information might be available from a large hospital system or primary care network, but it wouldn’t be comprehensive. So, for an analysis like the Salt Lake County agency’s, a researcher needs to find a substitute.

In this case, the researchers used estimates of Zodiac sign representation in the entire U.S. population, apparently calculated in 2012. Not only are these numbers based on birthdays across the entire country (which could be pretty different from the birthdays in one Utah county!), they’re almost ten years old. There’s a lot of distance between these estimates and vaccination numbers among a 2021 Salt Lake City population.

The public health workers acknowledged that their analysis is “not super scientific” in interviews with the Salt Lake Tribune. Still, the widely-shared Twitter post itself could do with a few more caveats, in my opinion.

For more on the issues with the Salt Lake County department’s analysis, see this Substack post by Christopher Ingraham.

-

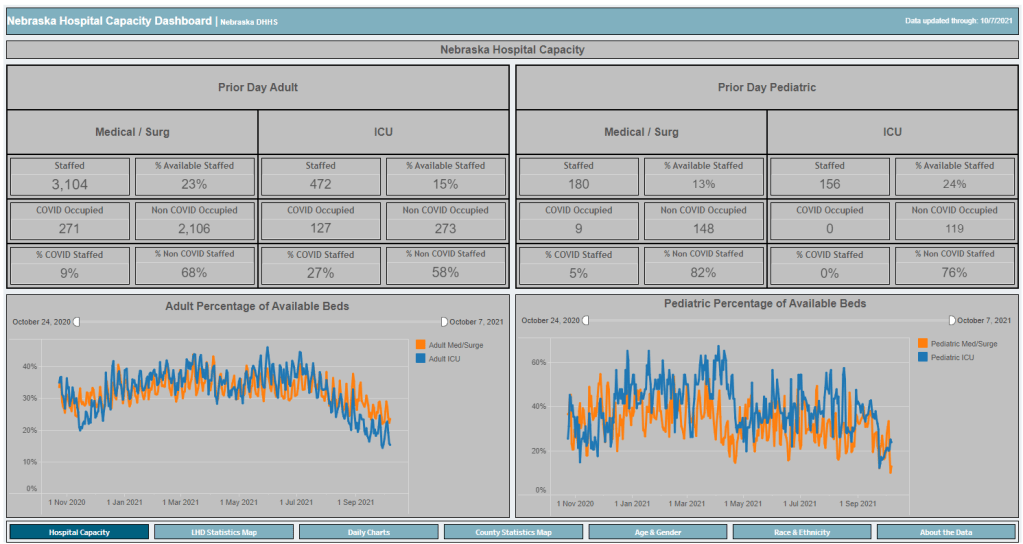

Nebraska’s dashboard is back… Or is it?

Nebraska’s new, most likely short-lived, Hospital Capacity Dashboard. Screenshot taken on October 10. Last week, I called out the state of Nebraska for basically demolishing its COVID-19 vaccination data. I wrote that the state’s “Weekly Data Update” report now includes just two metrics: variants of concern and vaccine breakthroughs. This came after the state discontinued its comprehensive COVID-19 dashboard in late June. (You can see screenshots of the old dashboard here.)

While I was correct in writing that Nebraska’s weekly update is now incredibly sparse, I missed that the state has, in fact, brought back its COVID-19 dashboard—kind-of. A New York Times article by Adeel Hassan and Lisa Waananen Jones alerted me to this update.

Instead of resuming updates of the state’s previous dashboard, Nebraska’s state public health agency has now built a new, less comprehensive one, called the Nebraska Hospital Capacity Dashboard. As you might expect from the title, this new dashboard focuses on hospitalization data, such as the share of hospital beds available state-wide and by local public health region.

But this new dashboard also includes some trends data (new cases, tests, and vaccinations by day, etc.) and demographics data. The demographics data are similar to what Nebraska provided on its old dashboard, reporting total cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and vaccinations by race, ethnicity, age, and gender.

So, allow me to correct last week’s post: Nebraska is currently reporting more vaccination data than what the state is posting on its weekly reports page. However, the new dashboard, is short-lived, according to the NYT:

On Sept. 20, after coronavirus hospitalizations surpassed 10 percent of the state’s capacity of staffed hospital beds, [Nebraska Governor Pete] Ricketts announced that county-level case data would once again be made public on a new “hospital capacity” state dashboard.

But he said the data will disappear again if the number drops below 10 percent on a 7-day rolling average. And the state is still not reporting county-level deaths.

Governor Ricketts ordered the new Hospital Capacity dashboard to be developed after public health experts and state legislators pushed for Nebraska to report more COVID-19 data. With limited state-level data and just a few Nebraska counties providing their own pandemic reports, residents were unable to see how the virus was spreading in their communities for all of July and August—when the Delta surge was at its worst.

The new dashboard is a victory for Nebraska’s public health and medical experts. But state residents have very limited access to testing, leaving some experts to think the data on this dashboard may be “vast underestimates,” the NYT reports.

Nebraska is not alone in cutting down on COVID-19 data reporting in recent months. Florida switched from a detailed dashboard and daily updates to pared-down weekly updates in June, and other states have stopped reporting on weekends or made other cuts. While the CDC and HHS continue to update their datasets daily, a lack of detailed data at the state level may heighten the challenge of another virus surge, if we see one this winter.

More state data

-

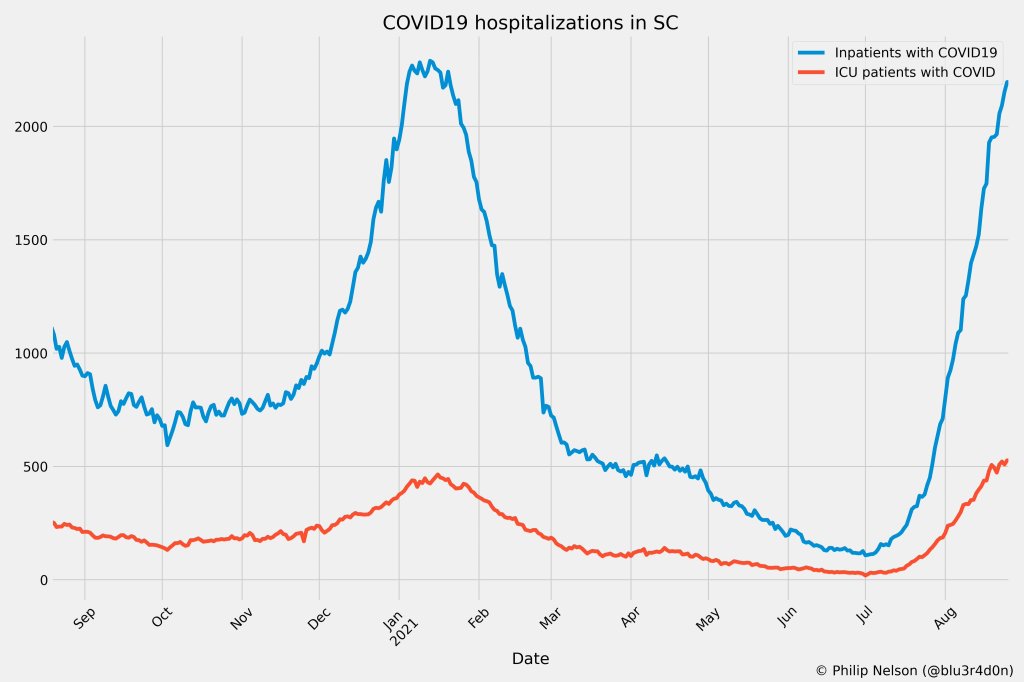

One data researcher’s journey through South Carolina’s COVID-19 reporting

By Philip Nelson

COVID-19 hospitalizations in South Carolina, as of August 26. Posted on Twitter by Philip Nelson. If you post in the COVID-19 data Twitter-sphere, you’re likely familiar with Philip Nelson, a computer science student at Winthrop University—and an expert in navigating and sharing data from the state of South Carolina. Philip posts regular South Carolina updates including the state’s case counts, hospitalizations, test positivity, and other major figures, and contributes to discussions about data analysis and accessibility.

I invited Philip to contribute a post this week after reading his Tweets about his ongoing challenges in accessing his state’s hospitalization data. Basically, after Philip publicized a backend data service that enabled users to see daily COVID-19 patient numbers by individual South Carolina hospital, the state restricted this service’s use—essentially making the data impossible for outside researchers to analyze.

To me, his story speaks to broader issues with state COVID-19 data, such as: agencies adding or removing data without explanation, a lack of clear data documentation, failure to advertise data sources to the public, and mismatches between state and federal data sources. These issues are, of course, tied to the systematic underfunding of state and local public health departments across the country, making them unequipped to respond to the pandemic.

South Carolina seems to be particularly arduous to deal with, however, as Philip describes below.

I’ve been collecting and visualizing South Carolina-related COVID-19 data since April 2020. I’m a computer science major at Winthrop University, so naturally I like to automate things, but collecting and aggregating data from constantly-changing data sources proved to be far more difficult than I anticipated.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I had barely opened Excel and had never used the Python library pandas, but I knew how to program and I was interested in tracking COVID-19 data. So, in early March 2020, I watched very closely as the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) reported new cases.

During the early days of the pandemic, DHEC provided a single chart on their website with their numbers of negative and positive tests; I created a small spreadsheet tracking these cases. After a few days, DHEC transitioned to a dashboard that shared county level data.

On March 23, I noticed an issue with the new dashboard. Apparently, someone had misconfigured authentication on something in the backend. (When data sources are put behind authentication, anyone outside of the organization providing that source loses access.) The issue was quickly fixed and I carried on with my manual entry, but this was not the last time I’d have to think about authentication.

Initially, I manually entered the number of cases and deaths that DHEC reported. I thought I might be able to use the New York Times’ COVID-19 dataset, but after comparing it to the DHEC’s data, I decided that I’d have to continue my own manual entry.

South Carolina’s REST API

In August 2020, I encountered some other programmers on Twitter who had discovered a REST API on DHEC’s website. REST is a standard for APIs that make it easier for developers to use services on the web. In this case, I was able to make simple requests to the server and receive data as a response. After starting a database fundamentals course during the fall 2020 semester, I figured out how to query the service: I could use the data in the API to get cases and deaths for each county by day.

This API gave me the ability to automate all of my update processes. By further exploring the ArcGIS REST API website, I realized that DHEC had other data services available. In addition to county-level data, the agency also provided an API for cases by ZIP code. I used these data to create custom zip code level graphs upon request, and another person I encountered built a ZIP code map of cases.

During August 2020, the CDC stopped reporting hospitalization data and the federal government shifted to using data collected by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Teletracking. DHEC provided a geoservice for hospitalizations, based off of data provided to DHEC by Teletracking on behalf of the HHS. I did some exploration of the hospitalization REST API and found that the data in this API was facility-level (individual hospitals), updated daily. I aggregated the numbers in the API based on the report date in order to provide data for my hospitalization graph. At the time, I didn’t know that the federal government does not provide daily facility level data to the public.

In October 2020, DHEC put their ZIP code-level API behind authentication. I voiced my displeasure publicly. In late December 2020, DHEC put the API that contained county level cases and deaths behind authentication. At this point, I began to get frustrated with DHEC for putting things behind authentication without warning, but I kind-of gave up on getting the deaths data out of an API. Thankfully, DHEC still provided an API for confirmed cases, so I switched my scripts to scrape death data from PDFs provided by DHEC each day. I didn’t like using the PDFs because they did not capture deaths that were retroactively moved from one date to another, unlike the API.

I ran my daily updates until early June 2021, when DHEC changed their reporting format to a weekday-only schedule. I assumed that we’d seen the last wave of the pandemic and that, thanks to readily available vaccines, we had relegated the virus to a containable state. Unfortunately, that was not the case — and by mid-July, I had resumed my daily updates.

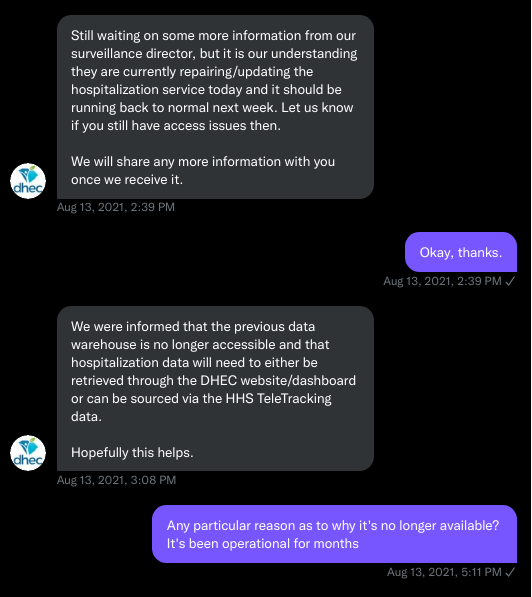

Hospitalization data issues

In August 2021, people in my Twitter circle became interested in pediatric data. I decided to return to exploring the hospitalization API because I knew it had pediatric-related attributes. It was during that exploration that I realized I had access to daily facility-level data that the federal government was not providing to the public; the federal government provides weekly facility-level data. My first reaction was to build a Tableau dashboard that let people look at the numbers of adults and pediatric patients with COVID19 at the facility level in South Carolina over time.

After posting that dashboard on Twitter, I kept hearing that people wanted a replacement for DHEC’s hospitalization dashboard which, at the time, only updated on Tuesdays. So, I made a similar dashboard that provided more information and allowed users to filter down to specific days and individual hospitals, then I tweeted it at DHEC. Admittedly, this probably wasn’t the smartest move.

I kept exploring the hospitalization data and found that it contained COVID-19-related emergency department visits by day, another data point provided weekly by HHS. After plotting out the total number of visits each day and reading the criteria for this data point, I decided I needed to make another dashboard for this. A day after I posted the dashboard to Twitter, DHEC put the API I was using behind authentication, again I tweeted my frustration.

A little while later, DHEC messaged me on Twitter and told me that they were doing repairs to the API. I was later informed that the API was no longer accessible, and that I would have to use DHEC’s dashboard or HHS data. The agency’s dashboard does not allow data downloads, making it difficult for programmers to use it as a source for original analysis and visualization.

I asked for information on why the API was no longer operational; DHEC responded that they had overhauled their hospitalization dashboard, resulting in changes to how they ingest data from the federal government. This response did not make it clear why DHEC needed to put authentication on the daily facility-level hospitalization data.

Twitter conversation between Philip and the South Carolina DHEC, shared by Philip. Meanwhile, DHEC’s hospital utilization dashboard has started updating daily again. But after examining several days’ worth of data, I cannot figure out how the numbers on DHEC’s dashboard correlate to HHS data. I’ve tried matching columns from a range dates to the data displayed, but haven’t been able to find a date where the numbers are equal. DHEC says the data is sourced from HHS’ TeleTracking system on their dashboard, but it’s not immediately clear to me why the numbers do not match. I’ve asked DHEC for an explanation, but haven’t received a response.

Lack of transparency from DHEC

I’ve recently started to get familiar with the process of using FOIA requests. In the past week, I got answers on requests that I submitted to DHEC for probable cases by county per day. This data is publicly accessible (but not downloadable) via a Tableau dashboard, but there is over 500 days’ worth of data for 46 counties. The data DHEC gave to me through the FOI process are heavily suppressed and, in my opinion, not usable.

This has been quite a journey for me, especially in learning how to communicate and collect data. It’s also been a lesson in how government agencies don’t always do what we want them to with data. I’ve learned that sometimes government agencies don’t always explain (or publicize) the data they provide, and so the job of finding and understanding the data is left to the people who know how to pull the data from these sources.

It’s also been eye-opening to understand that sometimes, I’m not going to be able to get answers on why a state-level agency is publishing data that doesn’t match a federal agency’s data. Most of all, it’s been a reminder that we always need to press government-operated public health agencies to be as transparent as possible with public health data.