Last week, I discussed the recent trend in states ending mask requirements in public schools, businesses, and other settings, by providing readers with some suggestions for encouraging safety during this push to “open everything” (that wasn’t already open). This week, more states are dropping safety measures; for example, Washington governor Jay Inslee announced that the state’s indoor mask mandate will end on March 21, though this change is also contingent on a low level of COVID-19 hospital admissions.

At the same time, some states are also making major shifts in the ways they collect and report COVID-19 data. State public health departments are essentially moving to monitor COVID-19 more like the way they monitor the flu: as a disease that can pose a serious public health threat and deserves some attention, but does not entirely dictate how people live their lives.

You may have seen this shift discussed as a movement to treat COVID-19 as “endemic.” An endemic disease, from an epidemiologist’s standpoint, is one that’s controlled at an acceptable level—it hasn’t been completely eradicated, but the levels of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are generally deemed as levels that can continue without major public health measures. For more on the topic, I recommend this post from epidemiologist Ellie Murray (whom I’ve quoted on this topic before).

We can argue—and many COVID-19 experts on Twitter are arguing—about whether this is the appropriate time to shift into endemic mode. Still, regardless of individual opinions, state public health departments are starting to make this shift, and I think it’s worthwhile to discuss how they’re doing it, particularly when it comes to data.

Here’s a brief roundup of four states that are shifting their COVID-19 data collection and reporting.

California

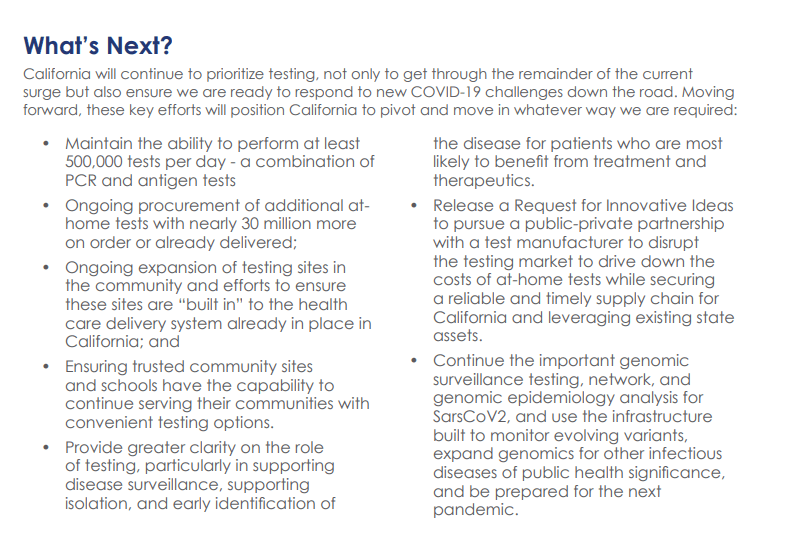

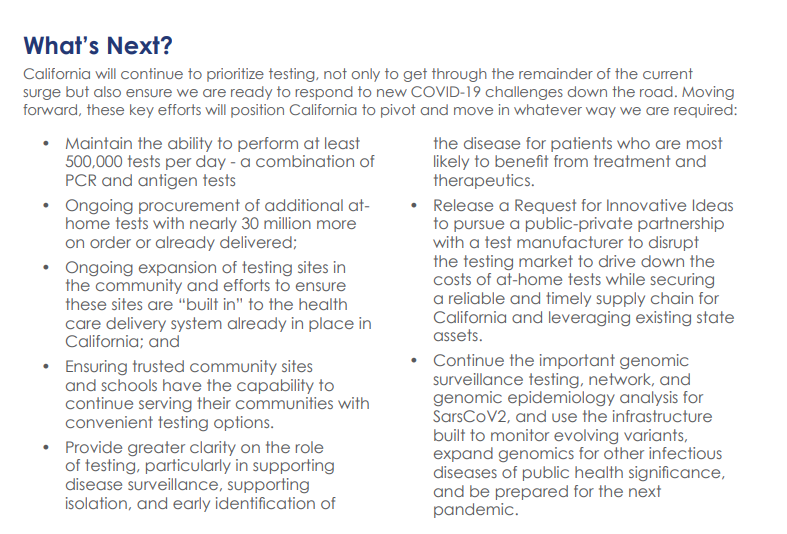

California made headlines this week for being the first state to officially shift into “endemic” policy for dealing with COVID-19. State officials have drafted a plan called “SMARTER”—which stands for Shots, Masks, Awareness, Readiness, Testing, Education, and Rx (treatment). I took a look at the plan, which reporters from NBC Bay Area kindly shared publicly on DocumentCloud.

Here are a few data-related highlights:

- State officials will “focus on hospital numbers” to gauge how California should react to potential new variants that may be more infectious or more capable of causing severe disease.

- Unlike some other states, California is maintaining testing capacity going forward, including an expansion of community testing sites and ongoing procurement of at-home antigen tests for public schools, long-term care facilities, and other institutions.

- Throughout the pandemic, California has invested in genomic sequencing for COVID-19 cases, as well as a statewide modeling tool that compiles several different forecasts. These surveillance tools will be further expanded to respond to COVID-19 and other infectious disease outbreaks.

- California also intends to “build a robust, regionally based wastewater surveillance and genome sequencing network” that can provide early warnings about new outbreaks.

- The plan includes a focus on equity: California leaders will monitor testing, cases, and other metrics in minority communities so that resources can be provided to address disparities if needed.

Missouri

Missouri started its shift to “endemic” in December, as the governor declared an end to the state’s public health emergency around COVID-19—even though cases were at their highest-ever level in the state. Now, the Missouri health department is preparing to change its data reporting accordingly, my colleague Derek Kravitz and I reported in the Missouri Independent this week. (The Independent, a nonprofit newsroom focused on Missouri’s state government, is a long-time collaborator of the Documenting COVID-19 project, where I work part-time.)

Here are the planned data changes highlighted in our story:

Case investigations and contact tracing, where local health departments’ staffers reach out to people exposed to the virus in workplace or other public settings, will cease, unless a new, more transmissive or deadly variant emerges;

Daily reports on COVID-19 cases and deaths by the state health department will be replaced by aggregate weekly reports. In some cases, metro health departments, including those in St. Louis and Springfield, will likely continue collecting and disseminating daily reports but the state will stop its reporting;

Positivity rates will be phased out, as they are already difficult to interpret, with many Americans having switched from PCR tests to at-home antigen tests. Most people don’t report their results to local health departments. Missouri officials in January said they were prepared to be a “trend setter” in eliminating positivity rate reporting.

Hospitalization data will become even more important, with state health officials hoping to make reporting more timely;

Wastewater surveillance will become a more relied-on data point for public health officials, as a way to spot COVID-19 early in its life cycle and identify potential hot spots. Missouri is a leader in wastewater surveillance, as the state has the highest number of collection sites reported on a new CDC dashboard.

Iowa

A couple of weeks ago, I called out the state of Iowa for decommissioning its two COVID-19 dashboards, one dedicated to vaccination data and one for other major metrics. (I’m still bummed out about this, to be honest! Iowa had one of my favorite/most chaotic dashboards to check as a COVID Tracking Project data entry volunteer.)

The change actually occurred this week: the old link to Iowa’s vaccination dashboard now goes to a 404 page, and all Iowa COVID-19 data are now consolidated in a single “COVID-19 reporting” page on the overall Iowa health department website.

Here’s a bit more information on Iowa’s data shift, from a press release by the state’s governor:

- Rather than reporting daily COVID-19 case numbers, vaccinations, and other data, Iowa is now providing weekly updates. The new, pared-down dashboard includes positive tests and death numbers over time, case and vaccination rates by county, and some demographic data.

- For more frequent COVID-19 reporting, the Iowa dashboard now directs residents to federal data sources. Iowa is still reporting daily to the federal government, as all states are required to do.

- The state health department “will continue to review and analyze COVID-19 and other public health data daily,” Governor Kim Reynolds said. But some teams focused on the COVID-19 response will return to pre-pandemic responsibilities.

- This reporting change is intended to align with “existing reporting standards for other respiratory viruses,” Gov. Reynolds said.

- Iowa is focusing on at-home tests with a program called “Test Iowa at Home,” in which residents can request to have a test kit sent to their homes for free. (It was unclear to me, from browsing the website, whether these are rapid antigen tests or PCR tests.) The state health department processes these tests and collects data from the program.

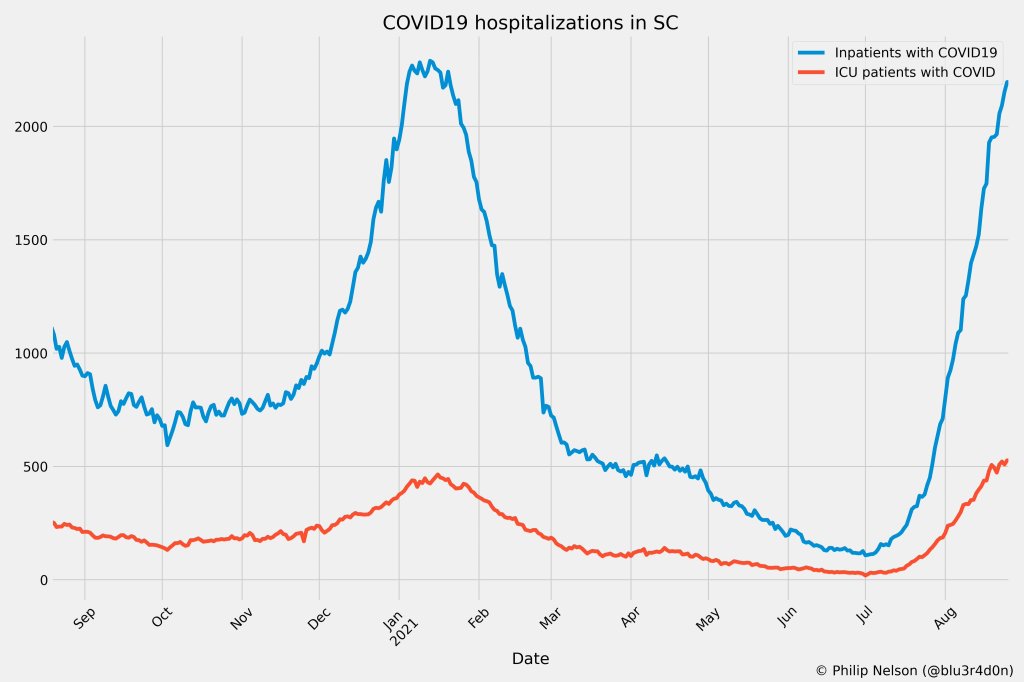

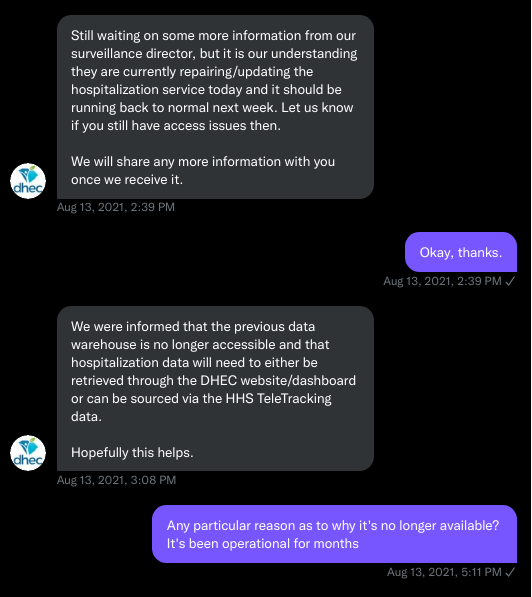

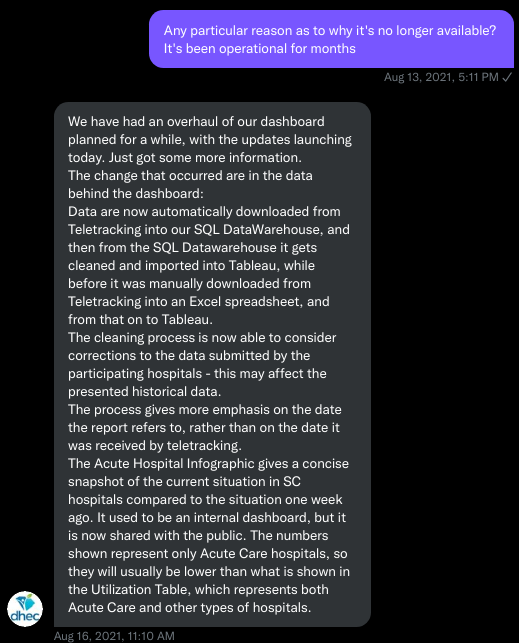

South Carolina

A Tweet from South Carolina data expert Philip Nelson alerted me to this one: not only is South Carolina shifting from daily to weekly data reports, the state is essentially ending all reporting of COVID-19 cases. This is paired with a gradual shutdown of testing sites in the state.

Here’s more info on South Carolina’s shift, based on a press release from the state health department:

- South Carolina’s health department will stop reporting daily COVID-19 case counts on March 15.

- The agency will continue to report COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths as important indicators of disease severity, but these will switch to a weekly update schedule rather than daily.

- The shift away from case reporting aligns with a greater focus on rapid at-home tests, which South Carolina’s health department says are “not reportable.” (While it’s true that the vast majority of rapid at-home test results are not reported, some jurisdictions, like D.C., allow residents to self-report their results!)

- South Carolina’s health department is planning to gradually shut down almost all public PCR testing sites in the state throughout the month of March. According to the department, these sites have seen “a significant decrease in demand” due to increased availability for rapid tests.

- The department is also discouraging regular testing for asymptomatic South Carolina residents, saying that individuals who are currently symptomatic or have a close contact who tested positive should be prioritized.

More news on this topic

- The CDC continues adding wastewater collection sites to its new dashboard. Two weeks ago, I wrote that only ten states had ten or more sites included on the dashboard; since then, three additional states have crossed that threshold: Illinois, Washington, and West Virginia. But the dashboard is still empty for the majority of states, indicating a lack of this important surveillance tool in much of the country.

- For an upcoming story, I recently interviewed Lauren Ancel Meyers, a modeling expert at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author on this fascinating paper about using hospital admissions and mobility data for pandemic surveillance. Meyers has considered cases to be a messy indicator throughout the pandemic, she told me. She finds hospital admissions to be more useful, as this metric will directly show how many people are seeking healthcare due to their COVID-19 symptoms.

- Another interesting paper, published in Nature this week, describes the use of machine learning models to drive COVID-19 testing at a university. The models could “predict which students were at elevated risk and should be tested,” the researchers write; students tested because of the models tended to be tested more quickly and were more likely to test positive than those identified through manual contact tracing or general surveillance. Such modeling could be used to augment the type of random sampling that Natalie Dean described in a recent article, shared in last week’s issue.

Are there any other states shifting their data reporting for an endemic COVID-19 state that I’ve missed? Email me or comment below and let me know!