- New vaccination data from the CDC: The CDC has started publishing vaccination data reflecting how many Americans have received COVID-19, flu, and RSV shots in fall 2023. These numbers are estimates, based on the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, as the agency is no longer directly compiling COVID-19 vaccinations from state and local health agencies. (See this post from last month for more details.) According to the estimates, about 28% of American adults have received a 2023 flu shot, compared to 10% who have received a 2023 COVID-19 shot. The numbers reflect poor communication about and accessibility challenges with this year’s COVID-19 vaccines.

- FDA approves a rapid COVID-19 test: Following the end of the federal public health emergency this spring, the FDA has advised companies that produce COVID-19 tests to submit their products for full approval, transitioning out of the emergency use authorizations that these tests received earlier in the pandemic. The FDA has now fully approved an at-home COVID-19 test: Flowflex’s rapid, antigen test. This is the second at-home test to receive approval, following a molecular test a few months ago. The Floxflex test “correctly identified 89.8% of positive and 99.3% of negative samples” from people with COVID-like respiratory symptoms, according to a study that the FDA reviewed for this approval.

- WHO updates COVID-19 treatment guidance: This week, the World Health Organization updated its guidance on drugs and other treatment options for severe COVID-19 symptoms. A group of WHO experts has regularly reviewed the latest evidence and updated this guidance since fall 2020. The update includes guidelines on classifying COVID-19 patients based on their risk of potential hospitalization, recommendations for drugs such as nirmatrelvir and corticosteroids, and recommendations against other drugs such as invermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Clinicians can explore the guidance through an interactive tool that summarizes the expert group’s findings.

- Gargling with salt water to reduce symptoms: Speaking of COVID-19 treatments: gargling with salt water may help people with milder COVID-19 symptoms recover more quickly, according to a new study presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s annual conference. The researchers compared COVID-19 outcomes among people who did and did not use salt water for 14 days while sick; those who used the treatment had lower risks of hospitalization and reported shorter periods of symptoms. This study has not yet been peer-reviewed and more research will be needed, but it’s still helpful evidence to back up salt water as a potential treatment (something I’ve personally seen recommended anecdotally in the last couple of years).

- Allergies as potential Long COVID risk factors: Another study that caught my attention this week: researchers at the University of Magdeburg in Germany conducted a review of connections between allergies and Long COVID. The researchers compiled data from 13 past papers, including a total of about 10,000 study participants. Based on these studies, people who have asthma or rhinitis (i.e. runny nose, congestion, and similar symptoms, usually caused by seasonal allergies) are at higher risk for developing Long COVID after a COVID-19 case. The researchers note that this evidence is “very uncertain” and more investigation is needed; however, the study aligns with reports of people with Long COVID getting diagnosed with mast cell activation syndrome (or MCAS, an allergy-related condition).

- Dropping childhood vaccination rates: One more notable study, from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): vaccination rates for common childhood vaccines are declining among American kindergarteners, according to CDC research. CDC scientists reviewed data reflecting the childhood vaccinations that are required by 49 states and D.C. for the 2022-23 school year, and compared those numbers to past years. Overall, 93% of kindergarteners had completed their state-required vaccinations last school year, down from 95% in the 2019-20 school year, while vaccine exemptions increased to 3%. In 10 states, more than 5% of kindergarteners had exemptions to their required vaccines—signifying increased risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in schools, according to the CDC.

Tag: rapid tests

-

Sources and updates, November 12

-

Sources and updates, October 29

- Healthcare worker burnout trend backed up by new data: The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a growing burnout crisis among healthcare workers in the U.S., as many articles and scientific papers have explored in the last couple of years. Two studies from the past week add more data to back up the trend. CDC researchers shared the results of a survey of about 2,000 workers, finding that workers were more likely to report poor mental health and burnout in 2022 than in 2018, while harassment and a lack of support at work contributed to increased burnout. Another research group (at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Washington University in St. Louis) also surveyed healthcare workers and found that many experienced food insecurity and financial challenges; workers with worse employer benefits were more likely to increase these challenges.

- Viral load not necessarily associated with symptoms: This paper is a rare, relatively recent update on how COVID-19 symptoms connect to viral load, or the amount of virus that a patient has in their respiratory tract. The higher a patient’s viral load, the more likely they are to infect others, making this an important metric for contagiousness. Researchers at Emory University studied viral loads in about 350 people diagnosed with Omicron variants between April 2022 and April 2023. Patients tended to have their highest viral loads around the fourth day of symptoms, a change from studies done on earlier variants (when viral loads tended to peak along with symptoms starting). As Mara Aspinall and Liz Ruark explain in their testing newsletter, these results have implications for rapid at-home tests, which are most accurate when viral loads are high: if you’re symptomatic but negative on a rapid test, keep testing for several days, and consider isolating anyway.

- Updated vaccines are key for protection: Another recent paper, in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, examines how last year’s bivalent COVID-19 vaccines worked against recent coronavirus variants using data from the Kaiser Permanente health system. The study included records from about 123,000 people who had received at least the original vaccine series, examining health system visits from August 2022 to April 2023. People who received an updated vaccine in fall 2022 were significantly less likely to have severe COVID-19, the researchers found. “By mid-April, 2023, individuals previously vaccinated only with wild-type vaccines had little protection against COVID-19,” the researchers wrote. This year’s updated vaccine may have a similar impact through spring 2024.

- Gut fungi as a potential driver for Long COVID: Long COVID, like ME/CFS and other chronic conditions, may be associated with problems in patients’ gut microbiomes, i.e. the communities of microorganisms that live in our digestive systems. A new paper in Nature Immunology from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine hones in on one fungal species that may be particularly good at causing problems. The species, Candida albicans, can grow in the intestines of severe COVID-19 and Long COVID patients, triggering to inflammation and other immune system issues. This paper describes results from patient samples as well as a mouse model mimicking how this fungal species grows in COVID-19 patients’ guts.

- Another potential Long COVID biomarker: One more notable Long COVID paper from this week: researchers at the University of Alberta studied blood samples from people with the condition, and compared their results to people who had acute COVID-19 but didn’t go on to develop long-term symptoms. The scientists used machine learning to develop a computer model differentiating between blood composition of people who did and didn’t develop Long COVID. They identified taurine as one specific amino acid that might be particularly important, as levels of taurine were lower among patients with more Long COVID symptoms. The study could be used to inform diagnostic tests of Long COVID, as well as potential treatments to restore taurine.

-

Sources and updates, September 24

- Free at-home tests from the federal government: The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Postal Service are restarting their program offering free COVID-19 rapid, at-home tests. Starting tomorrow, every U.S. household will be able to order four more tests at covidtests.gov. HHS also announced that it’s buying about 200 million further rapid tests from major manufacturers, paying a total of $600 million to twelve companies. Of course, four tests per household is pretty minimal when you consider all the exposures people are likely to have this fall and winter—but it’s still helpful to see the federal government acknowledge a continued need for testing.

- New grants support Long COVID clinics: The HHS and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also announced a new grant program for clinics focused on Long COVID, aiming to make care for this condition more broadly accessible to underserved communities. Nine clinics across the country have received $1 million each, with the opportunity to renew their grants over the next five years. (At least, that’s my interpretation of the HHS press release, which says $45 million in total is allocated to this program.) This is a pretty significant announcement, as it marks the first time that the federal government is specifically funding Long COVID care; funding has previously gone to RECOVER and other research projects.

- CDC announces new disease modeling network: One more federal announcement: the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics has established a new program to improve the country’s disease surveillance, working with research institutions across the country. The CDC has awarded $262.5 million of funding to the thirteen institutions participating in this program, which it’s calling the Outbreak Analytics and Disease Modeling Network. These institutions will develop new surveillance tools, test them in small-scale projects, and scale up the successful options to broader public health systems. For more context on the CDC’s forecasting center, see my story for FiveThirtyEight last year.

- Testing wildlife for COVID-19: Speaking of surveillance: researchers at universities and public agencies are collaborating on new projects aiming to better understand how COVID-19 is spreading and evolving among wild animals. One project, at Purdue University, is focused on developing a test to better detect SARS-CoV-2 among wild animals. A second project, at Penn State University, is focused on increased monitoring, with plans to test 58 different wildlife species and identify sources of transmission from animals to humans. Both projects received grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and involve collaboration with state environmental agencies.

- Paxlovid access falls along socioeconomic lines: A new study, published this week in JAMA Network Open, examines disparities in getting Paxlovid. Researchers at the National Institutes of Health analyzed public data on Paxlovid availability as of May 2023. Counties with higher poverty, less health insurance coverage, and other markers of high socioeconomic vulnerability had significantly less access to Paxlovid than better-off counties, the scientists found. Meanwhile, a separate study (also in JAMA Network Open last week) found that Paxlovid and another antiviral treatment, made by Merck, both remain very effective in reducing severe COVID-19 symptoms. Improving access to these treatments should be a top priority for the public health system.

- Undercounted COVID-19 cases in Africa: One more study that caught my attention this week: researchers at York University in Canada developed a mathematical model to assess how many people actually got COVID-19 in 54 African countries during the first months of the pandemic. Overall, only 5% of cases in these countries were actually reported, the researchers found, with a range of reporting from 30% in Libya to under 1% in São Tomé and Príncipe. A majority of cases in these countries were asymptomatic, the models suggested, indicating many people may not have realized they were infected. The study shows “a clear need for improved reporting and surveillance systems” in African countries, the authors wrote.

-

Sources and updates, August 6

- Novavax vaccine safety: This week, the CDC published new data in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) affirming the safety of Novavax’s COVID-19 vaccine. Unlike the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines (which use the virus’ genetic information), the Novavax vaccine works by inserting direct copies of the coronavirus spike protein into the body. It was authorized in summer 2022 as a primary series or booster for people who may be unable or unwilling to receive an mRNA vaccine. The CDC found that, among 70,000 Novavax vaccine doses administered between July 2022 and March 2023, no new safety concerns emerged.

- Insurance coverage for COVID-19 tests: Insurance companies have covered COVID-19 tests very unevenly since the federal health emergency ended this spring. But that could change, if an advisory panel called the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that the federal government require insurers to cover COVID-19 testing. The panel is exploring this option, reports Sarah Owermohle at STAT News, though it could face legal challenges.

- Breath test for COVID-19: A couple of weeks ago, I shared a new tool for detecting SARS-CoV-2 particles in the air, developed by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis. The same team has just published another paper, in ACS Sensors, about a similar tool that can diagnose a coronavirus infection using a patient’s breath. This breath test can detect the virus with as few as two breaths and in under 60 seconds, and is close in accuracy to a PCR test. The research team is working to continue testing this device and potentially manufacture it more broadly, according to a press release.

- COVID-19 spread among white-tailed deer: A recent paper in Nature Communications describes how SARS-CoV-2 has circulated widely among white-tailed deer across the U.S. The research team (which includes scienitsts at the CDC, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the University of Missouri) collected about 9,000 respiratory samples from deer in 26 states and Washington D.C. between fall 2021 and spring 2022. Hundreds of the samples were positive for SARS-CoV-2, leading the team to study genetic sequences and study how the virus had evolved in this population. The team’s full data are available online. (H/t Data Is Plural.)

-

Sources & updates, June 25

- Commonwealth Fund releases 2023 state health scorecard: This week, health research organization the Commonwealth Fund published its 2023 rankings of state health systems. These rankings are an extensive data source for anyone seeking to better understand the decentralized health system in the U.S., and may be particularly useful for local reporters looking for data on how their state compares to others. In the 2023 rankings, the researchers have added new metrics related to care and health outcomes for women, mothers, and infants. This year’s data also highlight preventable deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, and state efforts to take people off of Medicaid following the pandemic emergency’s end.

- New advisory about Long COVID and mental health: The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a federal health agency under the overall Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), published a detailed advisory explaining the mental health implications of Long COVID. This advisory is directed at primary care doctors who may be seeing Long COVID among their patients, as well as others in the medical community who may benefit from the information. SAMHSA highlights that mental health symptoms may result from a coronavirus infection itself as well as from the stress and social isolation that long-haulers experience. For more on this topic, check out this article I wrote last year.

- Rapid test accuracy can vary widely: A common question that I’ve received from readers in the last few months has been, “How accurate are rapid tests with newer variants?” A new study, published last week in the journal Microbiology Spectrum, offers some insight. The researchers (a team at CalTech) found that rapid tests still work to detect the coronavirus, but their accuracy varies based on viral load and specimen type. Tests that involved swabbing the patient’s throat (along with their nose) were significantly more accurate than nose swabs alone. Tests conducted later in the course of a patients’ infection, when they had higher viral loads, were also more accurate, though some patients never tested positive on rapid tests despite testing positive on PCR. My takeaway here: swabbing your throat and testing multiple times help improve accuracy, but the best option is always to get a PCR if you can.

- CDC and state agencies track reinfections: Another new study, published this week in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, examines coronavirus reinfections in the era of Omicron. Researchers at the CDC and 18 state and local health departments collaborated to track reinfections from September 2021 through December 2022, finding that these infections went up significantly when Omicron arrived in late 2021. The median time between infections ranged from 269 to 411 days, the researchers found, suggesting that Americans may expect to be sick with COVID-19 once or twice a year while our Omicron baseline persists.

- COVID-19 risk and air pollution exposure: One more study I wanted to highlight this week: researchers at Hasselt University in Belgium tracked the air pollution exposures of about 330 COVID-19 patients at hospitals in Belgium. Patients who were exposed to worse air pollution prior to their admission experienced more severe COVID-19 outcomes, including longer hospitalization and admission to the ICU. This paper provides further confirmation that poor air quality and COVID-19 can be compounding health problems for many people.

- Data problems persist with non-COVID vaccines: The CDC’s vaccine advisory committee met this week to discuss two new RSV vaccine candidates, recently approved by the FDA for seniors. While the CDC committee did vote to recommend these vaccines, I was struck by discussion (in Helen Branswell’s coverage for STAT) that the experts said they did not have sufficient data to make a truly informed decision. I’ve written a lot about data issues for COVID-19 vaccines; the same decentralized health system problems that make it hard to track COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness also apply to products for other diseases.

-

Sources and updates, June 11

- Quantifying Long COVID’s impact on day-to-day life: A new study published this week in the BMJ is one of the first I’ve seen to focus not on Long COVID’s symptoms, but on how it impacts quality of life for patients. Researchers at University College London assessed life impacts for about 3,700 Long COVID patients using surveys in an online health platform. The surveys found that “Long COVID can leave people with worse fatigue and quality of life than some cancers, yet the support and understanding is not at the same level,” study coauthor Dr. William Henley said in a statement about the research. This study confirms what I’ve heard from many long-haulers in interviews over the last couple of years.

- Long COVID and ME/CFS similarities: Another notable Long COVID paper: two leading experts on chronic illness, Dr. Anthony Komaroff at Harvard Medical School and W. Ian Lipkin at Columbia University, wrote a detailed review identifying commonalities between Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a debilitating condition with symptoms similar to Long COVID that often occurs after infection. ME/CFS has long been under-recognized and understudied, but there are still lessons from this condition that can inform Long COVID research and lead to answers for both diseases. The review paper points to directions for future study.

- Metformin for Long COVID: One more Long COVID paper: a study published this week in The Lancet shares results from a Long COVID clinical trial at the University of Minnesota, which found that the diabetes drug metformin reduces the risk of developing long-term symptoms when patients take it early in the course of a COVID-19 case. I shared this study when it was first posted as a preprint in March, and also spoke to one of its authors for my STAT/MuckRock story about the RECOVER initiative. I’m glad to see that the major findings haven’t changed in this peer-reviewed version; metformin appears to be a promising treatment option, though more study is needed.

- At-home test receives FDA approval: This week, the FDA approved an at-home, rapid COVID-19 test made by the company Cue Health. It’s the first at-home test to receive full approval, as these tests have previously received Emergency Use Authorization under public health emergency rules. With the federal emergency over, the FDA is encouraging test companies to apply for full approval so that at-home COVID-19 tests can be distributed (and marketed) like other commonly-available health products. The emerency authorizations still apply for tests that don’t have full approval yet, though.

- COVID-19 Medicaid rules led to more coverage for children: For the first three years of the pandemic, federal rules tied to the public health emergency forbid states from kicking their residents off of Medicaid. The policy led to a significant increase in Americans with health insurance—and that includes children, according to a new paper published this week in Health Affairs. For states that changed their Medicaid rules for children due to the pandemic policy, coverage increased by about 5% from 2019 to 2021, representing thousands of kids who were able to get healthcare more easily. Of course, these kids and their family members are now likely to lose their health insurance, as the federal policy ended in April.

- Animal behaviors changed during 2020 lockdowns: Remember when, in the early days of the pandemic, big cities with more stringent lockdowns saw more wild animals than normal? A new paper from a large coalition of scientists, published this week in Science, finds that this pattern wasn’t just anecdotal: animal behavior really did change. The scientists compiled a large dataset of animals tracked with GPS, representing 2,300 individuals from 43 different mammal species, and compared their behaviors in spring 2020 to the same period in 2019. Animals living in areas under strict lockdowns were more likely to travel outside their normal ranges, the researchers found.

-

Answering reader questions about wastewater data, rapid tests, Paxlovid

I wanted to highlight a couple of questions (and comments) that I’ve received recently from readers, hoping that they will be useful for others.

Interpreting wastewater surveillance data

One reader asked about how to interpret wastewater surveillance data, specifically looking at a California county on the WastewaterSCAN dashboard. She noticed that the dashboard includes both line charts (showing coronavirus trends over time) and heat maps (showing coronavirus levels), and asked: “I’m wondering what the difference is, and which is most relevant to following actual infection rates and trends?”

My response: Wastewater data can be messy because environmental factors can interfere with the results, and what may appear to be a trend may quickly change or reverse course (this FiveThirtyEight article I wrote last spring on the topic continues to be relevant). So a lot of dashboards use some kind of “risk level” metric in addition to showing linear trends in order to give users something a bit easier to interpret. See the “virus levels” categories on the CDC dashboard, for instance.

Personally, I like to look at trends over time to see if there might be an uptick in a particular location that I should worry about, but I find the risk level metrics to be more useful for actually following infection rates. Of course, every dashboard has its own process for calculating these levels—and we don’t yet have a good understanding of how wastewater data actually correlate to true community infections—so it’s helpful to also check out other metrics, like hospitalizations in your county.

Rapid test accuracy

Another reader asked: “Is there any data on the effectiveness of rapid tests for current variants like Arcturus? I’m hearing more and more that they are working less and less well as COVID evolves.”

My response: Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any specific data on rapid test effectiveness for recent variants. Early in the Omicron period, there were a few studies that showed the rapid tests still worked for that variant. The virus has obviously evolved a lot since then, but there is less interest in and fewer resources for evaluating these questions at this point in the pandemic, so it’s hard to say whether the continued mutations have had a significant impact on test effectiveness.

I think it’s important to flag, though, that rapid tests have never been highly accurate. People have tested negative on rapids—only to get a positive PCR the next day—since these tests were first introduced in spring 2021. The tests can be helpful for identifying if someone is contagious, with a high viral load, but are less accurate for people without symptoms. So, my recommendation with these tests is always to test multiple times, and to get a PCR if you have access to that. (Acknowledging there is less and less PCR access these days.) Also, if you were recently exposed to COVID-19, wait a few days to start rapid testing; see more details in this post from last year.

Double dose of Paxlovid

Another reader wrote in to share their experience with accessing Paxlovid during a recent COVID-19 case. The reader received a Paxlovid prescription, which led to a serious alleviation of symptoms. But when she experienced a rebound of symptoms after finishing the Paxlovid course, she had a hard time getting a second prescription.

“Fauci, Biden, head of Pfizer and CDC director got a second course of Paxlovid prescribed to them,” the reader wrote. “When I attempted to get this, my doctors pretended I was crazy and said this was never done.” She added that she’d like to publicize the two-course Paxlovid option.

My response: I appreciate this reader sharing her experience, and I hope others can consider getting multiple Paxlovid prescriptions for a COVID-19 case. The FDA just provided full approval to Pfizer for the drug, which should alleviate some bureaucratic hurdles to access. I also know that current clinical trials testing Paxlovid as a potential Long COVID treatment are using a longer course; 15 days rather than five days. The results of those trials may provide some evidence to support a longer course overall.

If you have a COVID-19 question, please send me an email and I’ll respond in a future issue!

-

At-home tests, wastewater: COVID-19 testing after the public health emergency ends

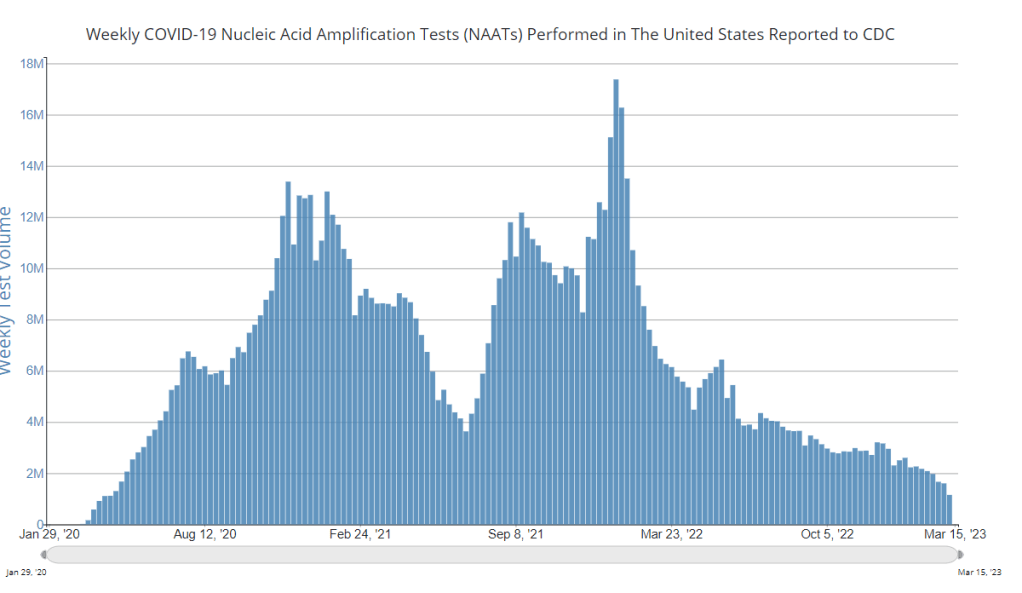

Nationwide, fewer people are getting lab-based COVID-19 tests now than at any time since the start of the pandemic. Chart via the CDC. When the public health emergency ends this spring, COVID-19 testing is going to move further in two separate directions: rapid, at-home tests at the individual level, and wastewater testing at the community level.

That was my main takeaway from an online event last Tuesday, hosted by Arizona State University and the State and Territory Alliance for Testing. This event discussed the future of COVID-19 testing following the public health emergency, with speakers including regulatory experts, health officials from state agencies, and executives from diagnostic companies.

“The purpose of testing has shifted” from earlier in the pandemic, said Dr. Thomas Tsai, the White House’s COVID-19 testing coordinator, in opening remarks at the event. Public health agencies previously used tests to monitor COVID-19 in their communities and direct contact-tracing efforts; now, individual tests are mostly used for diagnosing people, and the resulting data are widely considered to be a major undercount of true cases.

While the speakers largely agreed about the continued value of rapid, at-home tests (for diagnosing people) and wastewater surveillance (for tracking COVID-19), they saw a lot of challenges ahead for both technologies. Here are some challenges that stuck out to me.

Challenges for rapid, at-home tests:

The public health emergency’s end won’t have an immediate impact on which COVID-19 tests are available, health policy researcher Christina Silcox from Duke University explained at the event. But, in the coming months, the FDA is likely to also end its emergency use authorization for COVID-19 diagnostics. As a result, companies that currently have tests authorized under this emergency will need to apply for full approval. Relatively few rapid tests are currently approved in this way, so the change could lead to fewer choices for people buying tests.

At the same time, it will become harder for many Americans to access rapid tests. After the federal emergency ends, private insurance companies will no longer be required to cover rapid tests. Some insurance providers might still do this (especially if large employers encourage it), said Amy Kelbik from McDermott+Consulting, but it will no longer be a universal option. At the same time, Medicare will stop covering rapid tests; Medicaid coverage will continue through fall 2024.

In light of these federal changes, state health officials at the ASU event talked about a need for continued funding to support rapid test distribution from state and local agencies. “Testing will continue to inform behavior, but will become drastically less available,” said Heather Drummond, testing and vaccine program leader at the Washington State Department of Health. Washington has led a free test distribution program, but it’s slated to end with the conclusion of the federal health emergency, Drummond said; she’d like to see services like this continue for the people who most need free tests.

Drummond and other health officials also discussed the challenges of educating people about how to interpret their test results, as COVID-19 guidance becomes less widely available. The vast majority of rapid, at-home test results are not reported to public health agencies—and, based on the event’s speakers, this isn’t a problem health agencies are particularly interested in devoting resources to solving right now. But as rapid tests become the default for diagnosing COVID-19, continued outreach will be needed on how to use them.

Also, as I’ve written before, some PCR testing infrastructure should still be maintained, for cases when someone needs a more definitive test result or wants documentation in case of long-term symptoms. PCR test access will likely get even worse after the federal health emergency ends, though, as insurance plans will also stop covering (or cover fewer costs for) these tests.

Challenges for wastewater surveillance:

Overall, wastewater surveillance is the best source for community-level COVID-19 data, speakers at the ASU event agreed. Official case numbers represent significant undercounts of true infections, and hospitalizations (while more reliable) are a delayed indicator. Wastewater data are unbiased, real-time, population-level—and the technology can be expanded to other common viruses and health threats, health officials pointed out at the event.

But wastewater surveillance is still very uneven across the U.S. It’s clear just from looking at the CDC’s map that some states have devoted resources to detailed wastewater testing infrastructure, with a testing site in every county—while others just have a handful of sites. Funding uncertainty likely plays a role here; speakers at the event expressed some confusion about the availability of CDC funds for long-term wastewater programs.

The CDC’s wastewater surveillance system has also faced challenges with standardizing data from different testing programs. And, at state and local agencies, health officials are still figuring out how to act on wastewater data. Agencies with more robust surveillance programs (such as Massachusetts, which had two officials speak at the ASU summit) may be able to provide success stories for other agencies that aren’t as far along.

Broader testing challenges:

For diagnostic company leaders who spoke at the event, one major topic was regulatory challenges. Andrew Kobylinski, CEO and co-founder of Primary.Health, said that the FDA’s test requirements prioritize highly accurate tests, even though less sensitive (but easier to use) tests might be more useful in a public health context.

Future COVID-19 tests—and tests for other common diseases—may need a new paradigm of regulatory requirements that focus more on public health use. At the same time, health agencies and diagnostic companies could do more to collect data on how well different test options are actually working. While it’s hard to track at-home tests on a large scale, more targeted studies could help show which tests work best in specific scenarios (such as testing after an exposure to COVID-19, or testing to leave isolation).

Company representatives also talked about financial challenges for developing new tests, particularly as interest in COVID-19 dies down and as recession worries grow this year. While a lot of biotech companies dove into COVID-19 over the last three years, they haven’t always received significant returns on their investments. For example, Lucira, the company behind the first flu-and-COVID-19 at-home test to receive authorization, recently filed for bankruptcy and blamed the long FDA authorization process.

Mara Aspinall, the ASU event’s moderator and a diagnostic expert herself, ended the event by asking speakers whether COVID-19 has led to lasting changes in this industry. The answer was a resounding, “yes!” But bringing lessons from COVID-19 to other diseases and health threats will require a lot of changes—to regulatory processes, funding sources, data collection practices, and more.

More testing data

-

Sources and updates, March 5

- FDA authorizes joint COVID/flu rapid test, but there’s a catch: Late last week, the FDA issued emergency use authorization to the U.S.’s first at-home, rapid test capable of detecting both COVID-19 and the flu. This could be a really useful tool for people experiencing respiratory symptoms, since COVID-19 and flu can appear so similar. But you might not be seeing this test on pharmacy shelves anytime soon: Lucira Health, the test’s manufacturer, just declared bankruptcy. And the company actually blamed FDA authorization delays for contributing to its financial situation, as it had produced supplies anticipating a fall/winter sale of tests. Brittany Trang at STAT News reported on the situation; read her story for more details.

- COVID-19 surveillance stressed out essential workers: For a new report, the nonprofit Data & Society interviewed 50 essential workers from meatpacking and food processing, warehousing, manufacturing, and grocery retail industries about their experiences with COVID-19 surveillance efforts, like temperature checks and proximity monitoring. Overall, workers found that these surveillance measures added time and stress to the job but did not actually provide information about COVID-19 spread in their workplaces. (Companies often cited privacy concerns as a reason not to share when someone got sick, according to the report.) The report shows how health data often doesn’t make it back to the people most impacted by its collection.

- Vaccinations vs. Long COVID meta-analysis: A new paper published this week in the BMJ examines how COVID-19 vaccination impacts Long COVID risk. The researchers (at Bond University in Australia) performed a meta-analysis, compiling results from 16 prior studies. While the studies overall showed that vaccination can decrease risk of getting Long COVID after an infection (and may reduce symptoms for patients already sick with Long COVID), the studies were too different in their methodologies to actually allow for “any meaningful meta-analysis,” the authors noted. To better study this question, more rigorous clinical trials are needed, the researchers wrote.

- Tracking Long COVID with insurance data: Another notable Long COVID paper, published this week in JAMA Health Forum: researchers at the insurance company Elevance Health compared health outcomes for about 13,000 people with post-COVID symptoms compared to 27,000 who did not have symptoms. The researchers found that, in the one year following acute COVID-19, Long COVID patients had higher risks for several health outcomes, including strokes, heart failure, asthma, and COPD; people in the post-COVID cohort were also more likely to die in that year-long period. I expect insurance databases like the one used in this paper may become more common Long COVID data sources. Also, see Eric Topol’s Substack for commentary.

- FDA committee recommends RSV vaccine applications: Finally, a bit of good news on the “other respiratory viruses” front: the FDA’s vaccine advisory committee has recommended the agency move forward with two applications for RSV vaccines. Major pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) have been working on RSV vaccine options; while early data appear promising, clinical trials on both vaccines have found potentially concerning safety signals. The trial populations have been relatively small, making these signals difficult to interpret right now but worthy of additional study. As usual, Katelyn Jetelina at Your Local Epidemiologist has provided a great summary of the FDA advisory committee meeting.

-

Sources and updates, December 18

- Federal government opens up at-home test orders: The Biden administration has revived its program to mail out free COVID-19 at-home rapid tests, just in time for the holidays. Every household can now order four more tests. This feels pretty minimal (and late in the season) for a surge already overwhelming hospitals, but it’s better than nothing. Also, remember to report your results from these tests to the National Institutes of Health’s new portal!

- COVID-19 vaccines saved millions of lives: A new report from the Commonwealth Fund estimates the hospitalizations and deaths saved by two years of COVID-19 vaccines, in honor of the two-year anniversary of those shots first becoming available. About 80% of Americans have received at least one vaccine dose, the authors write, “with the cumulative effect of preventing more than 18 million additional hospitalizations and more than 3 million additional deaths.” The modeling data underlying this analysis are available for download.

- Congressional COVID-19 subcommittee issues final report: House Democrats on the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis recently released their final report, a 200-page document outlining how the U.S. should prepare for the next public health emergency. The report sums up information from three years of research and hearings, including some new findings from more recent investigations. It was released in time with the Subcommittee’s final hearing last Wednesday, which also focused on preparedness. Next year, the Republican-controlled House will have new COVID-19 priorities.

- Helix and CDC build multi-disease surveillance program: This week, leading viral surveillance company Helix announced that its partnership with the CDC has expanded to include sequencing other respiratory viruses, beyond COVID-19. The company will work with major health systems in Minnesota and Washington to track viral variants for the coronavirus, flu, RSV, and other pathogens—and will build infrastructure connecting that sequencing data to electronic health records. That second piece is particularly intriguing, as variant data usually aren’t connected back to health records in the U.S.

- State-level wastewater surveillance expansions: The University of Minnesota is working on a process to test wastewater for the coronavirus, flu, and RSV simultaneously, according to reporting by local outlet KARE11. A team of researchers at the university’s medical school currently test wastewater from 44 sewage treatment plants in Minnesota, and is working to broaden this work with grants from the CDC and state health department. Across the country, New Hampshire’s state health department has announced that it will start publishing results of its COVID-19 wastewater testing program online in the coming weeks. The New Hampshire program includes 14 plants across the state.