- Household Pulse Survey updates, expands Long COVID data: This week, the CDC and Census released an update of their Household Pulse Survey results on how Long COVID is impacting Americans. In addition to more recent data on Long COVID prevalence, the update includes new information on how adults with the condition find it limiting their day-to-day activities. The data shows that, out of all adults currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms, over 80% have some activity limitations and 25% have “significant” activity limitations. (For more context on this dataset, see my post from June.)

- NIH shares update on RECOVER study: Speaking of Long COVID, the National Institutes of Health’s Directors Blog shared a post this week with updates on its flagship RECOVER study to learn more about the condition. Major updates include: RECOVER’s current recruitment goal is 17,000 adults and 18,000 children; the NIH recently awarded more than 40 grants to research projects examining the condition’s underlying biology; and RECOVER is utilizing electronic health records to track patients over time. While this is all valuable progress, patient advocates have expressed concerns about limited involvement by post-viral chronic illness experts in RECOVER so far.

- Paxlovid is going under-utilized, study finds: A new report from the health records company Epic Research provides evidence that Paxlovid reduces severe COVID-19 outcomes: patients over age 50 who received the antiviral drug were about three times less likely to be hospitalized, compared with those who didn’t. The study also found, however, that eligible Americans aren’t taking advantage of this treatment. Out of about 570,000 people who “could have received Paxlovid” between March and August 2022, only 146,000 (about one in four) actually got prescriptions. Paxlovid needs to be better advertised and easier to access.

- New COVID-19 pill added to Medicines Patent Pool: And a new COVID-19 treatment option is becoming available internationally. Shionogi, a Japanese pharmaceutical company, recently signed an agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool, an international public health organization that facilitates increased drug access in low- and middle-income countries. The agreement allows other drug companies to make Shoinogi’s antiviral COVID-19 pill, called ensitrelvir fumaric acid, which has seen some promising results in clinical trials so far. Paxlovid and Molnupiravir (Merck’s antiviral pill) are already licensed by the pool.

- Patient access to electronic health records expands: This past Thursday, new federal rules took effect requiring healthcare companies to “give patients unfettered access to their full health records in digital format,” as STAT News reporter Casey Ross put it. This is a major milestone for the democratization of health data, as patient records have historically been locked in a labyrinth of private databases—though more public education is needed to help people actually take advantage of the new rules. Personally, I hope this is a first step towards more record-sharing between health institutions, which could be a key step for more comprehensive analysis in the future.

Tag: long haulers

-

Sources and updates, October 9

-

12 statistics showing the pandemic isn’t over

Long COVID and ME/CFS patients protest in front of the White House, telling Biden that the pandemic is not over and demanding action on their conditions. Image courtesy of ME Action. Last Sunday, 60 Minutes aired an interview with President Joe Biden in which he declared the pandemic is “over.”

“The pandemic is over,” Biden said, while walking through the Detroit Auto Show with 60 Minutes correspondent Scott Pelley. “We still have a problem with COVID. We’re still doing a lot of work on it. But the pandemic is over. If you notice, nobody’s wearing masks, everybody seems to be in pretty good shape.”

Most of the debate and dissection of this interview has focused on Biden’s statement that the “pandemic is over.” Is it, actually? (Epidemiologists say no.) Does he have the authority to declare it over? (No, that’s a job for the WHO.) Was his statement just reflecting what most Americans are already thinking? (Depends on who you call “most Americans.”)

See, I think the key part of Biden’s quote here actually comes at the end: “everybody seems to be in pretty good shape.” Seems to be is doing a lot of work here. In the interview, Biden is strolling through the auto show, through groups of unmasked people looking at car exhibits.

He is not actually talking to these bystanders, asking them whether they’ve lost loved ones to COVID-19, lost work during the pandemic, or faced any lingering symptoms after catching the virus themselves. Biden also isn’t considering the people who were excluded from this auto show: the Americans who were left disabled with Long COVID, and those still taking safety precautions due to other health conditions.

Images of the auto show, like those of packed indoor restaurants or maskless stadiums, seem to suggest that, yeah, Americans no longer care about COVID-19. But there are plenty of other images that don’t make it into high-profile media settings like Biden’s interview.

Today, I invite you to consider a few of the images that Biden isn’t seeing. Here are 12 statistics showing how the COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a massive impact on Americans:

- At least 400 Americans are dying with COVID-19 every day, about 47,000 deaths total between June and September 2022. Daily death data tend to be underestimates, because it can take weeks to process death certificates (and numbers are often retroactively edited up). But we can still see that hundreds of people are dying each day. As Sarah Zhang points out in The Atlantic, this is several times the threshold experts set in early 2021 for calling the pandemic at an end.

- About 25,000 people are currently hospitalized with COVID-19 cases. Yes, many of the people included in this statistic probably entered the hospital for another reason, then tested positive as part of routine screening. But incidental coronavirus infections still put pressure on the hospitals caring for these patients, and can intersect with a wide variety of other health conditions, potentially causing long-term issues for patients.

- About 7.6% of adults are currently experiencing some form of Long COVID, as of early August. This estimate, which I pulled from the Census and CDC’s Household Pulse Survey, rises for certain demographics: almost 10% of women, 11% of transgender adults, 11% of adults with less than a high school diploma, and 15% of adults with a disability are currently experiencing Long COVID.

- Hundreds of Long COVID and ME/CFS patients protested at the White House and online on Monday. Biden’s statement coincidentally landed the night before a planned protest, in which patient-advocates called for the president to declare a national emergency around Long COVID and ME/CFS. The protest was covered in the New York Times, MedPage Today, the BMJ, and other outlets.

- 19 patients, patient-advocates, and experts testified at a New York City Council hearing about Long COVID and gender on Thursday. Long COVID patients and those with related conditions (like ME/CFS and HIV) talked about dismissals from doctors and inability to return to their pre-COVID lives. They called for more comprehensive medical care and other forms of financial and social support for patients. I covered the hearing for Gothamist/WNYC.

- About 2.5 million adults were recently out of work due to a COVID-19 case, either because they were sick themselves or were caring for a sick person. Another 1.6 million adults were out of work due to concern about getting or spreading COVID-19. These statistics come from the most recent iteration of the Household Pulse Survey, conducted from July 27 to August 8, 2022.

- About 2.2 million adults were recently laid off or furloughed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Another one million had their employers go out of business due to the pandemic, and 900,000 had their employers close temporarily due to COVID-19. These data are from the same Household Pulse Survey.

- Over 50 million adults experienced symptoms of anxiety for at least half the days in the last two weeks, at the time of the most recent Household Pulse Survey. Almost 40 million adults experienced symptoms of depression for at least half the days in the same two-week period.

- Over 80% of Americans still support the federal government providing free COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, and tests to anyone who needs them, according to an Axios-Ipsos poll conducted in early September. A past iteration of that poll, from March 2022, found that 74% of Americans reported they were “likely to wear a mask outside the home if COVID-19 cases surge again in their area.”

- About 3% of Americans, or around 12 million people, are immunocompromised and still have reason to take intense COVID-19 precautions. Immunocompromised people have been eligible for extra vaccine doses, but are still more vulnerable to both severe COVID-19 symptoms and Long COVID.

- Over one million seniors live in nursing homes, and almost one million more live in assisted living and other forms of long-term care facilities. Seniors in long-term care have represented a hugely disproportionate share of deaths from COVID-19, and the CDC just made its mask recommendations for these facilities much more lenient—putting many vulnerable adults at risk.

- 2.5 billion people worldwide still haven’t been vaccinated, according to estimates from Our World in Data. Bloomberg’s vaccine tracker estimates that, at the current pace of first doses administered, it will take another 10 months for just 75% of the global population to have received at least one COVID-19 shot. As long as COVID-19 continues to spread anywhere in the world, new variants can be a threat everywhere.

More on Long COVID

-

COVID source shout-out: Millions Missing protest

Flyer for the Long COVID and ME/CFS-led protest, happening tomorrow at the White House. Image via ME Action. Tomorrow afternoon, patient-advocates living with Long COVID and other chronic diseases will be at the White House demanding that the federal government act urgently to address these conditions. ME Action, an advocacy group focused on myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), is the leading organization behind the protest.

The protest’s demands include nationwide education on ME/CFS and Long COVID, education specifically for doctors in diagnosing these conditions, funding for research and potential treatments, and economic support for patients.

While the main event will take place in Washington, D.C., organizers are also encouraging people from other parts of the country to participate online. You can learn more about the event here. (I personally plan to watch and cover the protest remotely.)

Patient advocacy around Long COVID and related conditions like ME/CFS has grown mostly remotely over the last two years, so it’s a major milestone for patient groups to converge on the White House in an event like this one. For any journalists interested in covering the protest, feel free to email or DM me for background info, connections to organizers, etc!

-

Sources and updates, September 18

- COVID-19’s impact on the workforce: Economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research released a new working paper this week, showing that COVID-19 has “persistently” reduced the U.S.’s labor supply. Using data from the Census’ Current Population Survey, the researchers found that workers who had to take off at least a week from work due to COVID-19 were seven percentage points less likely to still be in the labor force a year later, compared to those who didn’t miss a week. Overall, Long COVID pushed about 500,000 people out of the workforce, the paper estimates. Notably, this estimate is much lower than the analysis from the Brookings Institution published last month; the gap between these two reports suggests a need for more robust data collection on Long COVID and work.

- Long COVID prevalence from a population survey: Last week, I shared a new preprint from Denis Nash and his team at the City University of New York, reporting on the results of a national survey used to determine true COVID-19 prevalence during the BA.5 surge. This week, Nash et al. shared another preprint from that same survey, focused on Long COVID. Based on the nationally-representative survey (sample size: about 3,000), the researchers estimate about 7.3% of U.S. adults are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms—matching estimates from the Household Pulse Survey. One-quarter of those Long COVID patients surveyed reported that their day-to-day life activities were significantly impacted.

- Lancet COVID-19 Commission shares lessons from the pandemic: The Lancet COVID-19 Commission is an interdisciplinary group of scientists convened by the journal to study the COVID-19 crisis and make recommendations for the future. In the group’s final report, released this week, the scientists focus on “failures of international cooperation” that have contributed to unnecessary illness and deaths. Those failures include delays in acknowledging that the coronavirus spreads through the air, not enough funding for low- and middle-income countries, “the lack of timely, accurate, and systematic data,” and more.

- COVID-19 archive of Dr. Fauci’s emails: The COVID-19 Archive is a project aiming to compile digital documents tracing the early phases of the pandemic. Its prototype iteration allows users to search and sort through the early-COVID inbox of Dr. Anthony Fauci, via email records contributed by investigative reporter Jason Leopold. (MuckRock, where I work part-time, is a collaborator on the project, but I’m not personally involved with it.)

- U.S. has active circulation of vaccine-derived polio: This week, the CDC and World Health Organization formally announced that the polioviruses spreading in New York state constitute active circulation of vaccine-derived polio. Most other countries that meet this WHO classification are developing nations in Africa, as well as Israel, the U.K., and Ukraine. For more on what exactly “vaccine-derived polio” means and how the disease made a comeback in the U.S., I recommend reading Maryn McKenna in WIRED.

- Neurological symptoms associated with monkeypox: Here’s one study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that caught my eye this week: the agency has identified two cases in which monkeypox patients faced inflammation in their brains (called encephalomyelitis), leading to neurological symptoms. Both patients were hospitalized and required weeks of rehab, including use of walkers. The CDC says these symptoms are rare but worth monitoring, and is encouraging local health agencies to report any further cases.

-

Sources and updates, July 24

- New CDC report on drug overdose deaths during the pandemic: Drug overdose deaths increased by 30% from 2019 to 2020, according to a new CDC report compiling data from 25 states and D.C. But this increase was higher for Black and Native Americans: deaths among these groups increased by 44% and 39%, respectively. The full report includes more details on how overdose deaths disproportionately occurred in Black and Native populations, as well as the need for more easily accessible treatments for substance abuse.

- CDC survey of public health workers: Another CDC report that caught my attention this week presented results from a national survey of state and local public health workers in 2021. Almost three in four of the workers surveyed were involved with COVID-19 response last year. The survey provides further evidence of burnout among public health workers: 40% of those surveyed reported that they intend to leave their jobs within the next five years.

- COVID-19 testing options: COVID-19 Testing Commons is a research group at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions that has compiled comprehensive information about COVID-19 tests available worldwide. You can search the database for tests by company, platform, type of specimen collected, regulatory status, and more. The group also recently compiled a report summarizing these testing options in the pandemic to date.

- Congressional hearing on Long COVID: This week, Congress’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis held a hearing specifically about Long COVID. Congressmembers heard from Long COVID patient advocates and researchers about the impacts of this condition and the urgent need for more research and support. I highly recommend reading or listening to the testimony of Hannah Davis, cofounder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, for a powerful summary of these impacts and needs. (If you’re watching the video: her testimony starts at about 28:50.)

- CDC recommends Novavax vaccine: The CDC has officially authorized Novavax’s COVID-19 vaccine, following the FDA authorization that I mentioned in last week’s issue. Novavax’s vaccine is protein-based, which is an older type of vaccine but has been less common for COVID-19; some experts are hopeful that people who have hesitated with the mRNA vaccines may be more likely to get Novavax. Dr. Katelyn Jetelina has a helpful summary of this vaccine’s potential impact at Your Local Epidemiologist.

- NYC prevalence preprint updated: I’ve linked a couple of times to this study from a group at the City University of New York, with the striking finding that an estimated one in five New Yorkers got COVID-19 during a two-week period in the BA.2/BA.2.12.1 surge. The researchers recently revised and updated their study, based on some feedback from the scientific community. Their primary conclusions are unchanged, lead author Denis Nash wrote in a Twitter thread, but the updated study includes some context about population immunity and NYC surveillance.

-

Two major Long COVID reports are coming in August

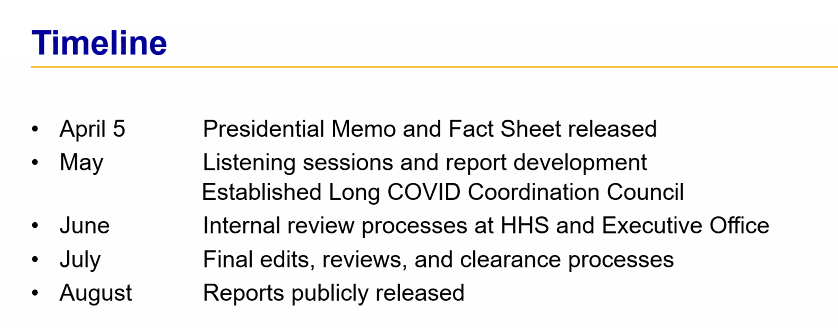

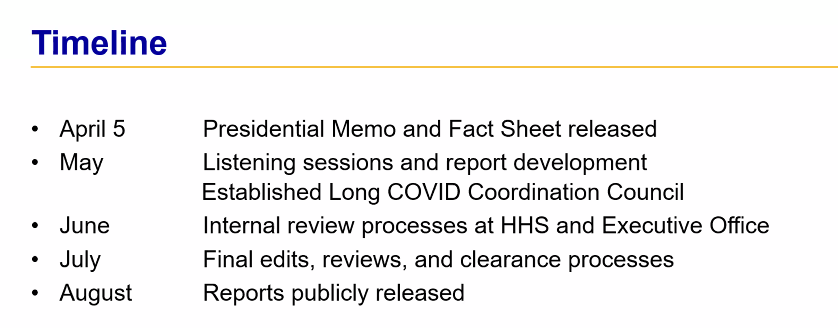

Two new White House/HHS reports about Long COVID and other long-term pandemic impacts will be released next month. Screenshot via Twitter. This past Friday, the White House and the Department of Health and Human Services held a briefing previewing two major reports about Long COVID.

The reports, which the Biden administration plans to release in August, will share government resources and research priorities for Long COVID, as well as priorities for other groups impacted long-term by the pandemic, such as healthcare workers and people who lost loved ones to COVID-19. Friday’s briefing served to give people and organizations most directly impacted by this work (particularly Long COVID patients) advanced notice about the reports and future related efforts.

It was also, apparently, closed to the press—a fact that I did not learn until I had already publicly livetweeted half of the meeting. I later confirmed with other journalist friends that the White House and HHS press offices did not do a great job of communicating the meeting’s supposedly closed status, as none of us knew this beforehand.

Officials honestly didn’t share much information at this briefing that I didn’t already know, so it’s not as though I obtained a huge scoop by watching it. (For transparency’s sake: I received a link to register for the Zoom meeting via the COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project’s listserv, and identified myself as a journalist when I signed up.)

Due to confusion around the briefing’s status and the fact that other attendees (besides myself) livetweeted it, I feel comfortable sharing a few key points from the call. If this gets me in trouble with the HHS press office, well… they’ve never answered my emails anyway.

Key points:

- These upcoming August reports are responding to a memorandum that the Biden administration issued in April calling for action on Long COVID.

- Over ten federal government agencies have been involved in producing the reports, which officials touted as an example of their comprehensive response to this condition.

- One report will focus on services for Long COVID patients and others facing long-term impacts from the pandemic. My impression is that this will mostly highlight existing services, rather than creating new COVID-focused services (though the latter could be developed in the future).

- The second report will focus on Long COVID research, providing priorities for both public and private scientific and medical research efforts. Worth noting: existing public Long COVID research is not going well so far, for reasons I have covered extensively.

- An HHS team focused on human-centered design has been pursuing an “effort to better understand Long COVID” (quoting from their web page). This project is currently wrapping up its first stage, and expects to publish a report in late 2022.

- Some Long COVID patients and advocates would like to see more urgent action from the federal government than what they felt was on display at this briefing.

Here are a couple of Tweets from advocates who attended:

I look forward to covering the reports when they’re released in August.

More Long COVID reporting

-

Staggering new Long COVID research, and a correction

The Census and NCHS are releasing new, comprehensive data on Long COVID prevalence based on a nationally representative survey. I’m doing another post dedicated to Long COVID research this week, unpacking a noteworthy new data source. Also, I have an update about a Long COVID study that I shared in last week’s issue.

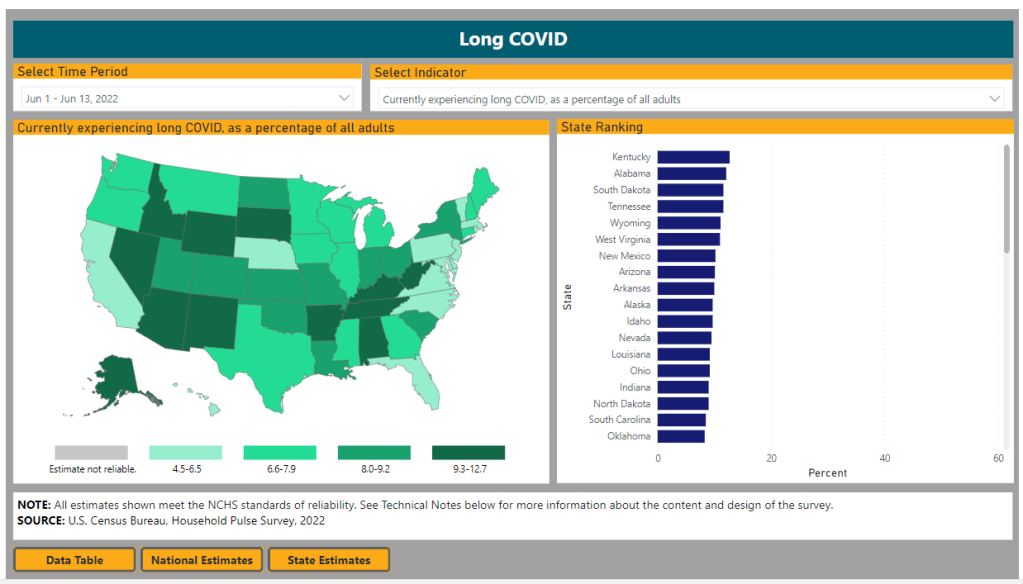

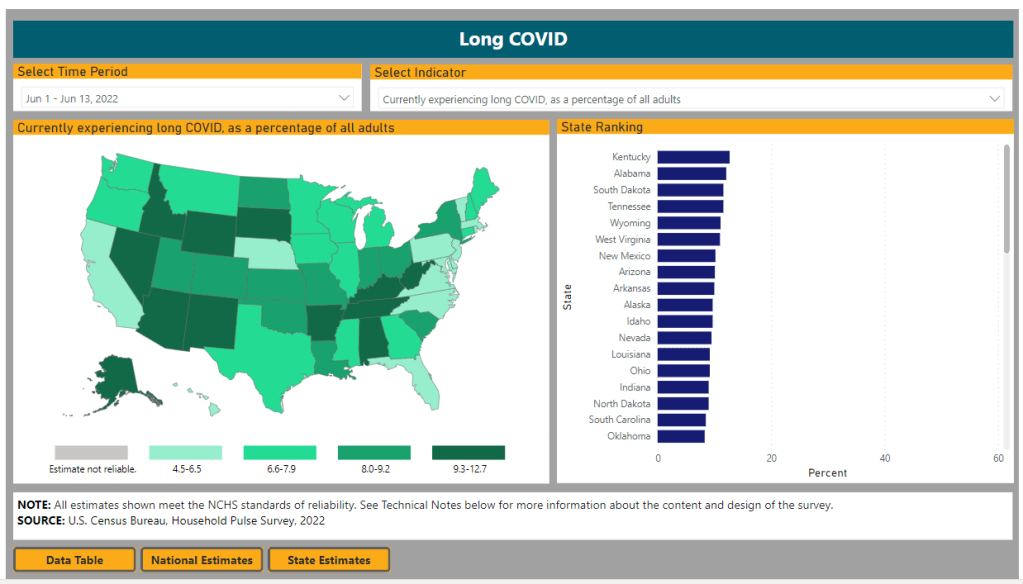

First: new data from the Household Pulse Survey suggests that almost 20% of Americans who got COVID-19 are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms. The Household Pulse Survey is a long-running Census project that provides data on how the pandemic has impacted Americans, with questions ranging from job loss to healthcare access.

In the most recent iteration of this survey, which started on June 1, the Census is asking respondents about Long COVID: specifically, respondents can share whether they had COVID-related symptoms that lasted three months or longer. The first round of data from this updated survey were released last week (representing respondents surveyed between June 1 and June 13), in a collaboration between the Census and the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

The numbers are staggering. Here are a few notable findings, sourced from the NCHS press release:

- An estimated 14% of all U.S. adults have experienced Long COVID symptoms at some point during the pandemic.

- About 7.5% of all U.S. adults are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms, representing about one in 13 Americans.

- Out of U.S. adults who have ever had COVID-19, about 19% are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms.

- Older adults are more likely to report Long COVID than younger adults, while women are more likely to report it than men.

- About 8.8% of Hispanic or Latino adults are currently experiencing Long COVID, compared to 6.8% of Black adults and 7.5% of White adults.

- Bisexual and transgender adults were more likely to report current Long COVID symptoms (12.1% and 14.9%, respectively) than those of other sexualities and genders.

- States with higher Long COVID prevalence included Southern states like Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee.

This study is a big deal. The Household Pulse Survey is basically the closest comparison that the U.S. has to the U.K.’s highly-lauded Office for National Statistics survey, in that the survey can collect comprehensive data from a representative subset of Americans and use it to provide national estimates.

In other words: two years into the pandemic, we finally have a viable estimate of how many people have Long COVID, and it is as large an estimate as Long COVID advocates warned us to expect. Plus, demographic data! State-by-state-data! This is incredibly valuable, moreso because the Household Pulse Survey will continue incorporating Long COVID into its questions.

Also, it’s important to note that Long COVID patients were involved in advocating for and shaping the new survey questions. Big thanks to the Patient-Led Research Collaborative and Body Politic for their contributions!

Next, two more Long COVID updates from the past week:

- Outcomes of coronavirus reinfection: A new paper from Ziyad Al-Aly and his team at the Veterans Affairs Saint Louis healthcare system, currently under review at Nature, explores the risks associated with a second coronavirus infection. They found that a second infection led to higher risk of mortality (from any cause), hospitalization, and specific health outcomes such as cardiovascular disorders and diabetes. “The risks were evident in those who were unvaccinated, had 1 shot, or 2 or more shots prior to the second infection,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

- NIH data now available for Long COVID research: The National Institutes of Health’s “All of Us” research program is releasing a dataset from almost 20,000 people who have had COVID-19 for scientists to study. The data come from clinical records, genomic sequencing, and patient-reported metrics; researchers can use them to examine Long COVID trends, similarly to the way in which Al-Aly’s team uses VA records to study COVID-19 outcomes.

And finally, a correction: Last week, I shared a paper published in The Lancet which indicated Long COVID may be less likely after an Omicron infection compared to a Delta infection. A reader alerted me to some criticism of this study in the Long COVID community.

Specifically, the estimates in the paper are much lower than those found by the U.K.’s ONS survey, which is considered more reliable. This Lancet paper was based not on surveys but on a health app which relies on self-reported, volunteer data. In addition, the researchers failed to break out Long COVID risk by how many vaccine doses patients had received, which may be a key aspect of protection.

Finally, as I noted last week, even if the risk of Long COVID is lower after an Omicron infection, the risk is still there. And when millions of people are getting Omicron, a small share of Omicron infections leading to Long COVID still leads to millions of Long COVID cases.

More Long COVID reporting

-

Star Trek predicted post-viral illness, but provided few tools to stop its spread

Spock finds some graffiti by an infected crew member in Star Trek: The Original Series episode The Naked Time. Image via the Memory Alpha wikipedia / Paramount Global. It’s been a somewhat slower week for COVID-19 news, so here’s something a little different: a reflection on a very old episode of Star Trek, in the context of post-viral illness.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, one of the new shows airing on Paramount+, has got me on a bit of a kick for the franchise. So, I’ve been rewatching The Original Series (TOS), which was one of my favorite TV shows in high school. (My girlfriend, who hasn’t seen any of the old Star Trek shows, has humored me by watching with me.)

Last week, we watched an episode I remembered as one of my favorites: The Naked Time, episode four in the first season. In this episode—which first aired in September 1966—a strange virus from an alien planet gets onto the Enterprise and infects a number of crew members. Once infected, crew members lose their inhibitions and behave as though emotionally naked; this leads to such iconic scenes as Spock “sobbing mathematically,” Sulu chasing his colleagues with a rapier, Uhura saying she’s neither fair nor a maiden, and so on.

Rewatching this episode two years into the pandemic, it struck me that Star Trek predicted—like it predicted iPads, cellphones, and so many other things—neurological symptoms triggered by a viral infection. While the Epstein-Barr virus was discovered in 1964, it would be decades before scientists understood how viruses like this one could cause fatigue, chronic pain, post-exertional malaise, and other similar symptoms.

Now, of course, the world is facing an epidemic of Long COVID, the most prevalent post-viral illness in history. Recent estimates from the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics suggest that two million people—or, 3% of the entire U.K. population—are living with Long COVID. And Long COVID is bringing renewed attention to other conditions like ME/CFS and dysautonomia, which have a lot of symptom overlap. It’s hard to deny that infectious diseases can have ramifications far beyond what we usually expect from a cold or the flu.

My girlfriend, who previously hadn’t seen most of TOS, has commented on how much early Star Trek episodes center around psychological dilemmas. Rather than watching phaser battles, we’re watching characters grapple with questions like, “How do you stop a hormonal teenager with infinite power?” and, “What would happen if Captain Kirk were split into good and evil halves?”

The Naked Time fits into this pattern, but it also feels more like a horror story than the others—especially when one watches it in the midst of a COVID-19 (and Long COVID) surge. Star Trek’s writers guessed, nearly 60 years ago, that an infectious disease could impact people’s minds. But here we are in 2022: Long COVID patients are still systematically discredited by doctors, unable to access treatment and financial support, and discarded by American leaders’ decision to “live with the virus.”

The episode also offers some lessons in infection control measures by showing us what not to do when confronted with a novel illness. The alien virus gets onto the Enterprise in the first place because a crew member, investigating dead scientists on an abandoned planet, takes off his hazmat suit to touch his face; without realizing it, he transmits the virus from an infected surface to his skin. And after this index case starts acting strangely on the ship, other crew members don’t isolate him until it’s too late. Funny how our basic public health measures haven’t changed since the 60s, either.

Anyway, because this is Star Trek, Dr. McCoy saves the day by quickly developing a cure for the virus. He has no trouble administering it to the crew—there’s no vaccine hesitancy on the Enterprise.

Still, this episode sticks with me, more now than when I first watched it years ago. With all the new technology we have now to fight COVID-19, the basic measures we can take to control a novel virus haven’t changed. And the stakes are higher than ever.

More on Long COVID

-

New Long COVID studies demonstrate danger of breakthrough cases

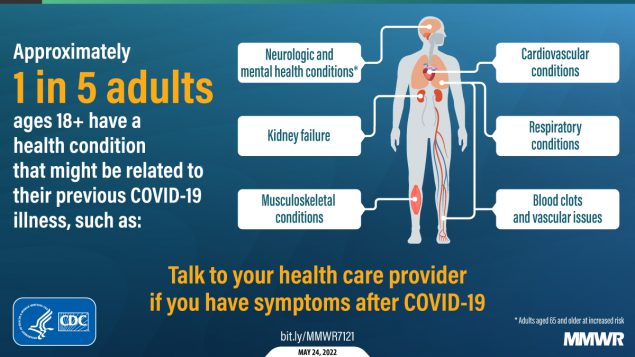

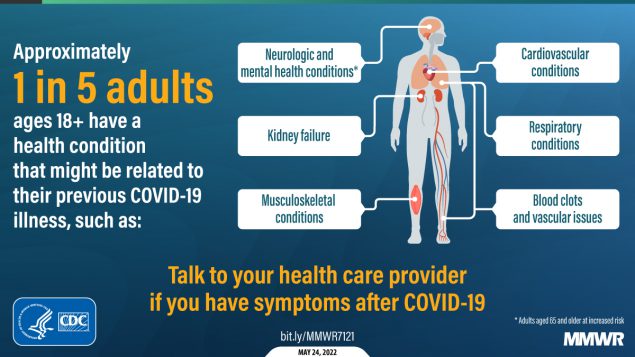

About one in five adults who have COVID-19 will face a health condition potentially related to long-term symptoms, a new CDC study found. Two new studies on Long COVID, published this week, provide an important reminder of the continued dangers this condition poses to people infected with the coronavirus—even after vaccination. Neither study provides wholly new information, but both are more comprehensive than many other U.S. papers on this condition as they’re based on large databases of electronic health records.

First: a team at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in St. Louis, Missouri used the VA’s extensive health records database to study breakthrough COVID-19 cases. The VA database includes more than 1,400 healthcare facilities serving veterans across the country; this St. Louis team has previously used it to characterize Long COVID symptoms more broadly, to study long-term heart disease risks of COVID-19, and for other research.

In the new paper, published this week in Nature Medicine, the researchers put together a cohort of about 34,000 people who had breakthrough COVID-19 infections. They compared this group to larger control groups of people who hadn’t been infected and people who had been infected prior to vaccination, along with comparisons to the seasonal flu.

Vaccination does reduce the risk of Long COVID, the researchers found: people with breakthrough cases were 15% less likely to report Long COVID symptoms than those who were infected prior to vaccination. Breakthrough Long COVID patients were notably less likely to have blood clots and respiratory symptoms than non-breakthrough patients.

But a risk reduction of 15% is pretty minimal, compared to the protection that vaccination offers against COVID-related hospitalization and death. Moreover, for most Long COVID symptoms, patients who had breakthrough infections showed relatively little difference to those who had non-breakthroughs, the researchers found.

“Overall, the burden of death and disease experienced by people with breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection is not trivial,” lead researcher Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly wrote in a Twitter thread summarizing the study. That’s scientist speak for, “A breakthrough COVID-19 case can really fuck you up in the long term!” Later in his thread, Dr. Al-Aly advocated for additional public health measures—beyond simply vaccines—to reduce Long COVID risks.

And second: a paper from the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) last week, used electronic health records to examine overall Long COVID risk after an infection. These health records came from Cerner Real-World Data, a dataset including about 63.4 million records from over 100 health providers.

The CDC researchers identified about 353,000 adults who had received either a COVID-19 diagnosis or a positive test result between March 2020 and November 2021. They matched this group of COVID-19 patients with a larger cohort of people who hadn’t tested positive, then looked at the COVID-19 patients’ risks of developing further symptoms more than a month after they were diagnosed.

The findings are striking: About one in five COVID-19 survivors between the ages of 18 and 64 developed at least one “incident condition” (or, prolonged symptoms) that could be connected to their coronavirus infection. For COVID-19 survivors over age 65, that risk is one in four.

Among the patients who potentially developed Long COVID, common symptoms were blockages in the lungs and other respiratory issues. Seniors were also likely to develop neurological and mental health symptoms, and the CDC researchers warned that Long COVID in this older age group could be linked to an increased risk of strokes and neurocognitive conditions, such as Alzheimers.

In their paper, the CDC authors noted that patients represented in this health records database may not represent the U.S. overall, and that the methods used to identify possible Long COVID symptoms might be “biased toward a population that is seeking care.” Similar caveats apply to the VA study.

Still, both studies clearly show the risk of just “letting COVID-19 rip” through the U.S. population, even after widespread vaccination. Studies like these should be headlines in every news publication, warning people that COVID-19 is not as mild as many of our leaders would like us to believe.

Also, for journalists covering the pandemic: I highly recommend listening to this interview with Long COVID journalist and advocate Fiona Lowenstein, which aired on the WNYC show On the Media this weekend. (And I’m not just saying that because they plugged my recent story on the RECOVER study!) The Long COVID source list that Fiona and I collaborated on also continues to be a great resource for reporters covering this topic.

More Long COVID reporting

-

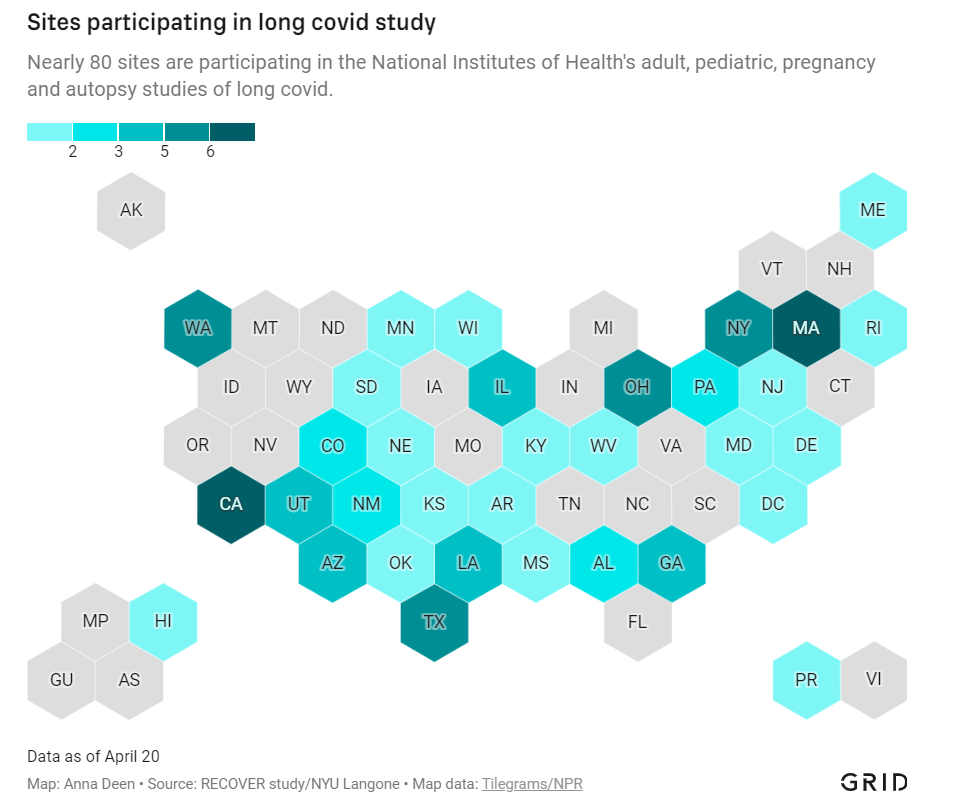

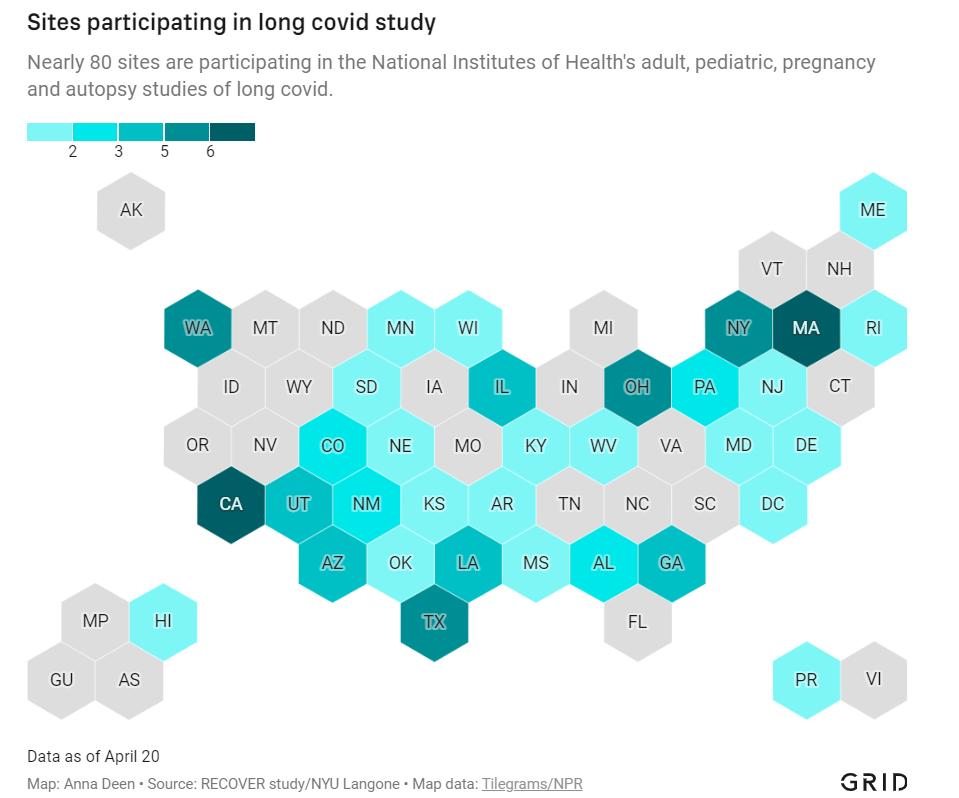

Five reasons why Long COVID research in the U.S. is so difficult

Medical and research institutions participating in the NIH’s Long COVID study are, unsurprisingly, concentrated in states with more scientific resources. Chart via Grid; see the full story for the interactive version! In December 2020, Congress provided the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with over $1 billion to study Long COVID. A couple of months later, the agency announced it would use this funding for an initiative called RECOVER: a large clinical trial aiming to enroll 40,000 patients, designed to answer long-standing questions about Long COVID and, eventually, identify potential treatments.

At the time, Long COVID patients and researchers were thrilled to see this massive investment. Long COVID patients may suffer from hundreds of possible symptoms, many of them debilitating; reports estimate that millions of people are out of work as a result of the condition. To anyone who has experienced Long COVID or talked to patients, as I have in my reporting, it’s clear that we need treatment options, and we need them yesterday.

But that promising NIH study is floundering: it’s moving incredibly slowly (with treatment trials potentially years off); it’s enrolled a tiny fraction of the 40,000 patients originally planned; it’s failing to meet the needs of patients from the communities most vulnerable to COVID-19; and it has been critiqued by patient advocates on concerns of trial setup, transparency, engagement, inclusion of other post-viral illnesses, and more.

I explored the concerns around RECOVER for a story in Grid, published last Monday. My piece highlights critiques from patient advocates and Long COVID researchers outside of RECOVER, while also discussing some of the broader problems that make it difficult for an initiative like this to succeed in the first place.

In the COVID-19 Data Dispatch today, I’d like to dig deeper into those broader problems and share some material from my reporting for the Grid story that didn’t make it into the final piece. Here are five reasons why the U.S. is not set up for success when it comes to Long COVID research, based on my interviews and research for the piece.

The NIH is designed for stepwise research, not “disruptive innovation.”

One of my favorite quotes in the story comes from David Putrino, who directs a lab at Mount Sinai focused on health innovations and was one of the first scientists in the U.S. to begin focusing on Long COVID. Putrino described how the NIH’s usual mode of operation does not work when it comes to novel conditions like Long COVID:

“What the NIH does very well, better than most national research organizations around the world, is supporting research that slowly develops small innovations in scientific knowledge,” Putrino said. The agency normally supports series of stepwise trials, climbing from one tiny aspect of research into a condition or treatment to the next.

This method is good for “long-term innovations that take 20 years,” Putrino said, but not for “disruptive innovation.” Treatments for long covid fall into the latter category: higher-risk, higher-reward science that may be viewed as a waste of government funding if it doesn’t pay off.

The same day as my Grid story was published, last Monday, STAT News published a story by Lev Facher discussing an oversight board at the NIH that was supposed to improve efficiency at the agency… and has not met for seven years. While this story doesn’t discuss Long COVID specifically, it provides some pretty clear context for why a study like RECOVER—which is different from anything the agency has done before—may be hard to get off the ground.

Here’s the final quote in Facher’s story, from Robert Cook-Deegan, founding director of the Duke Center for Genome Ethics, Law and Policy:

“About every 10 years, the National Academies [of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine] are asked to review NIH, and they make recommendations, most of which are ignored,” he said. The agency’s “large, inertial, and ponderous bureaucracy,” he added, is “not terribly open to criticism as a whole.”

Clinical trials are difficult and time-consuming to set up, especially when they involve new drugs.

My story also discusses the red tape that U.S. researchers face when they attempt to test potential treatments on human subjects. For such a clinical trial, researchers need to get approval from an Institutional Review Board (or IRB), an oversight board that ensures a study’s design protects the rights and welfare of people who participate in the trial.

In the U.S., this approval can take months, and may have extra steps for government-funded research. Researchers in other countries often have much shorter processes, Lauren Stiles, president of the research and advocacy organization Dysautonomia International, told me. She gave the example of a researcher in Sweden studying a potential Long COVID treatment with funding from her organization: for this researcher, the equivalent of IRB approval took a few hours rather than a few months.

Clinical trials in the U.S. also face extra hurdles when they involve studying new drugs, as our research system makes it easier for companies that develop these drugs to do new clinical trials than for outside academics to undertake similar studies. For example, Putrino told me that he would love to study the potential for Paxlovid, the antiviral drug for acute COVID-19, to treat Long COVID patients. But, he said, “I physically don’t have the bandwidth to fill out the hundreds of pages of documents” that would be required for such a trial.

A recent story in The Atlantic from Katherine J. Wu focuses further on Paxlovid’s potential as a Long COVID treatment—and how hard it is to study. Quoting from Wu:

The company is “considering how we would potentially study it,” Kit Longley, a spokesperson for Pfizer, wrote in an email, but declined to clarify why the company has no study under way. That frustrates Putrino, of Mount Sinai, who thinks Pfizer will need to spearhead many of these efforts; it’s Pfizer’s drug, after all, and the company has the best data on it, and the means to move it forward… When asked to elaborate on Paxlovid’s experimental status, the NIH said only that the agency “is very interested in long term viral activity as a potential cause of PASC (long COVID), and antivirals such as Paxlovid are in the class of treatments being considered for the clinical trials.”

The NIH has historically underfunded and undervalued research into other post-viral conditions.

When I shared my Grid story on Twitter this week, a lot of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), dysautonomia, and other post-viral illnesses said that the issues outlined in my piece felt very familiar.

After all, the NIH has been failing to fund research into their conditions for decades. Pots, one type of dysautonomia, received less than $2 million a year in NIH funding before the pandemic, Stiles told me. As a result, scientists and clinicians in the U.S. have fairly limited information on these other chronic conditions—in turn, limiting the sources that Long COVID researchers may use as starting points for their own work.

Long COVID patients share a lot of symptoms with ME, dysautonomia, and other chronic post-viral illness patients; in fact, many Long COVID patients have been diagnosed with these other conditions. According to one study by the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, almost 90% of Long COVID patients experience post-exertional malaise, the most common symptom of ME.

Despite the historical underfunding, post-viral illness researchers have still made major strides in studying this condition that could provide springboards for RECOVER. But the NIH trial isn’t using them, say experts I talked to. Here are a few paragraphs from an early draft of the story:

“NIH is approaching Long COVID as a brand-new phenomenon,” said Emily Taylor, an advocate at Solve ME, even though it has extensive overlaps with these other conditions. “We’re starting at square one, instead of starting at square 100.”

Long COVID patients and those ME have already come together organically to share tips and resources, she said. For example, Long COVID patients versed in medical research have educated ME patients on potential biological mechanisms for their chronic illness, while ME patients have shared methods for resting, pacing, and managing their conditions.

Experts in conditions like ME were not included in the trial’s leadership early on, and are now outnumbered in committees by cardiologists, respiratory experts, and others who have limited existing knowledge about post-viral illness. “Right now, there are three people with [dysautonomia] expertise on these committees,” Stiles said.

With the other two experts, Stiles has advocated for autonomic testing—a series of tests measuring the autonomic nervous system, believed to be a key driver of Long COVID symptoms—to be conducted on all RECOVER patients. A few of these tests have been added to the protocol, she said, but not the full list needed to get a comprehensive reading of patients’ nervous systems.

America’s fractured medical system and lack of broad knowledge on Long COVID have contributed to data gaps, access issues.

How does a Long COVID patient know that they have Long COVID? Ideally, more than two years into the pandemic, the U.S. medical system would have developed a consistent way of diagnosing the condition. Instead, patients are still getting diagnoses in a variety of ways, including (but not limited to):

- A positive PCR test, followed by prolonged symptoms.

- A positive rapid/at-home test, followed by prolonged symptoms.

- Prolonged symptoms, perhaps later associated with COVID-19 via a positive antibody test.

- Self-diagnosis based on prolonged symptoms.

- An official diagnosis of Long COVID from a doctor.

- An official diagnosis of ME, pots, mass cell activation syndrome, and/or other conditions from a doctor.

Patients also continue to face numerous barriers to formal Long COVID diagnoses, compounded by the fractured nature of the medical system. A lot of doctors and other medical providers—especially at the primary care level—still don’t know about the condition, and may make it hard for patients to learn that their prolonged fatigue is actually Long COVID. PCR or lab-based COVID-19 testing is also getting harder to access across the country, and many doctors won’t take a positive antigen test as proof of infection.

All of this means that the U.S. does not have a good estimate of how many Americans are actually suffering from Long COVID. There’s no central registry of patients who can be contacted for potential trials; there aren’t even basic demographic estimates of how many Long COVID patients are Black, Hispanic, or otherwise from marginalized communities. These data gaps make it hard for researchers studying Long COVID to set goals for patient recruitment.

And then, beyond receiving a diagnosis, actually getting care for Long COVID may require patients to wait weeks for appointments with specialists, contact many different doctors, and generally advocate for themselves in the medical system—while dealing with chronic, debilitating symptoms. As a result, as I wrote in the story:

The long covid patients who are believed by their doctors, who garner media attention, who serve on RECOVER committees — they’re more likely to be white and financially better-off, said Netia McCray, a Black STEM entrepreneur and long covid patient who has enrolled in the trial.

So far, RECOVER has not been doing much to combat this inherent bias in the patients who know about the trial (and about their own condition) and are able to sign up for participation.

Clinical trials in the U.S. are not typically set up in a way that prioritizes patient engagement, especially chronically ill patient engagement.

One major concern from Long COVID patient advocates involved with RECOVER is that the trial has not prioritized patient engagement—which should be a priority, considering all the medical bias that patients have faced while they’ve become experts in their own condition over the last two years.

Here’s a bit more detail on this issue, taken from an early draft of my Grid story:

Patients serving on the committees are dramatically outnumbered by scientists, creating an “intimidating” environment that makes it hard to speak up about their needs, said Karyn Bishof, founder of the COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project. This feeling is exacerbated when scientists on the committees are misinformed about Long COVID and dismiss patients’ experiences, she said.

Some scientists on the committees are receptive to patient input, representatives told me. Still, the structure is not in their favor: not only are patents outnumbered, it’s also a challenge for them to simply show up to committee meetings. Many Long COVID patients are, by definition, dealing with chronic symptoms that are not conducive to regular meeting attendance. Some are managing a barrage of doctors appointments, jobs, caregiving responsibilities, and more.

For instance, a second patient representative on a committee with Lauren Stiles—who serves as a representative because she has suffered from Long COVID in addition to other forms of dysautonomia—once missed a meeting because she had to go to the hospital. “If I wasn’t there, no patient would have been represented at all,” Stiles said.

Patients are compensated for their time in meetings, but not for hours spent doing other research outside those calls. And there’s no structure for patient representatives to coordinate more broadly; patients are operating in silos, with limited information about what representatives on other committees may be doing.

The NIH has potential models for improving this structure; it could draw from past HIV/AIDS clinical trials that had oversight from that patient community, advocate JD Davids told me. And leaders of RECOVER have acknowledged that they need to improve: as I highlighted in the story, trial leadership met with patient advocates earlier this month to discuss potential changes:

[Lisa McCorkell, advocate and researcher from the Patient-Led Research Collaborative] said that the meeting made it clear that the NIH and RECOVER leadership understand that improving patient engagement is key to the study’s success. “We agreed to work together to strengthen trust, improve representation of patients, and ensure greater accountability and transparency,” she said in an emailed statement.

The pressure is on for the NIH and RECOVER leadership to follow up on their promises. I, for one, intend to continue reporting on the trial (and on Long COVID research more broadly) as much as possible.

More Long COVID reporting