- Real-time detection of coronavirus in the air: A new study, published this week in Nature Communications, describes a tool to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 particles. Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis developed this tool; it works by collecting aerosols in a container and screening them for chemical properties matching the coronavirus spike protein. In the researcher’s proof-of-concept study, the detector tool was able to detect coronavirus particles with 77% to 83% accuracy, and could detect the virus when it was present at relatively small volumes. If the tool holds up to further tests, it could be valuable for monitoring healthcare settings and other public places.

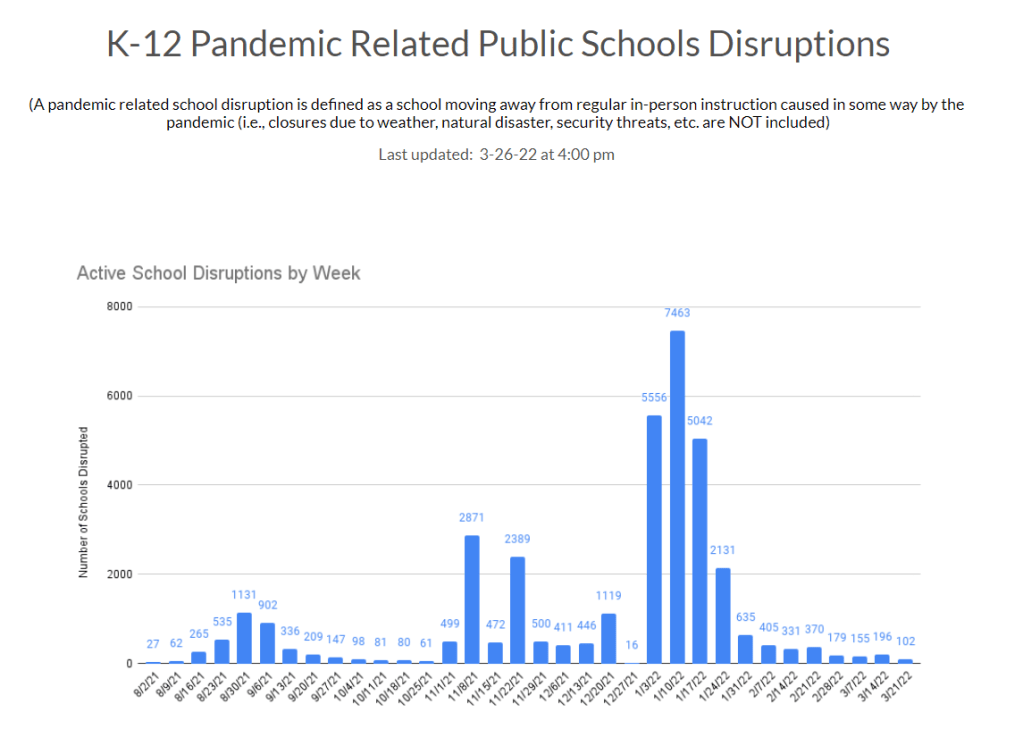

- Routine respiratory virus testing at K-12 schools: Another study about testing, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: researchers in Kansas City, Missouri regularly tested students and staff members at the public school district for SARS-CoV-2, the flu, RSV, and several other common respiratory viruses. About 900 participants opted into monthly testing for the 2022-23 school year, for a total of 3,200 tests conducted. Overall, about one in four tests were positive for at least one respiratory virus. Pre-K students had the highest positivity rate (40%), while rhinovirus/enterovirus was most commonly detected. The study shows how many viruses are going around in school settings, as well as the potential value of testing for reducing spread.

- Predicting COVID-19 activity with Google searches: COVID-19 data commentators have long suspected that online trends indicating people were losing their sense of smell or taste in large numbers could predict an upcoming surge. (Remember the Yankee Candle Index?) Well, a new study in the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal provides some evidence for this pattern. Researchers at Yale and Columbia Universities compared Google search trends for “loss of smell” and “loss of taste” to COVID-19 hospitalization and death numbers in five countries. They found a strong correlation between these searches and COVID-19 increases for major COVID-19 waves. So, even as official data become less available, online trends may still be a good indicator.

- Estimating infection rates from mortality data: COVID-19 mortality data can be used to work backward and estimate true infection rates, according to a new paper in Science by researchers at the University of California Davis and the University of the Basque Country (in Spain). The scientists used a machine learning model to analyze death reports from several European countries, essentially predicting infection rates in reverse. Their analysis found that lockdowns and mask requirements, among other COVID-19 safety measures, had a major impact on transmission, one of the authors said in a press release. Mortality data continues to present a useful tool for tracking COVID-19’s full impact.

- Long COVID cohort study suggests full recovery may be rare: One more notable new study, shared by The Lancet as a preprint: researchers at a hospital in Barcelona shared the results of a study following Long COVID patients for two years. The study followed 548 people, including 341 with Long COVID and 207 who did not have long-term symptoms after acute COVID-19. Only 26 (7.6%) of the Long COVID patients recovered during the two-year follow-up period, according to symptom surveys and diagnostic testing. Hannah Davis, a patient-researcher at the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, shared additional highlights and takeaways from the study in a Twitter thread.

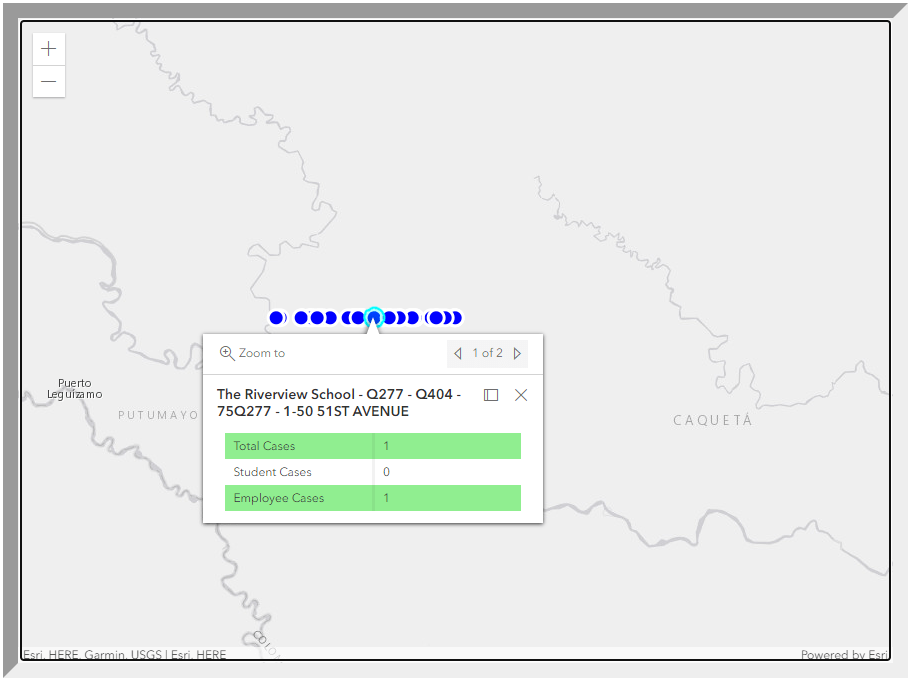

- New bill to strengthen wastewater surveillance: Finally, a bit of hopeful news: three U.S. senators just introduced a bipartisan bill that would strengthen the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS). The bill would specifically expand NWSS to include surveillance for other public health threats, and would enable it to provide more funding to state and local health agencies. Cory Booker from New Jersey, Angus King from Maine, and Mitt Romney from Utah are the three sponsors. I’m not a political reporter, so I won’t pretend to know how likely this bill’s chances are of passing, but I hope it’s a step toward making the U.S.’s wastewater surveillance infrastructure permanent.

Editor’s note, July 23, 2023: An earlier version of this post misstated the virus most commonly detected in the Kansas City schools study. (It was rhinovirus/enterovirus, not RSV.)