This week, the FDA’s vaccine advisory committee had a two-day meeting to discuss booster shots for Moderna’s and Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccines. From the outside, these meetings may have appeared fairly straightforward: the committee voted unanimously to recommend booster shots for both vaccines.

But in fact, the discussions on both days were wide-reaching and full of questions, touching on the many continued gaps in our knowledge about the need for additional vaccine doses. The FDA committee continues to make decisions based on rather limited data, as do other top U.S. officials. Case in point: on Thursday, the committee was asked to consider data from Israel’s booster shot campaign—which is utilizing Pfizer vaccines—as evidence for Moderna boosters in the U.S.

In the Moderna vote on Thursday afternoon, committee member Dr. Patrick Moore, a virologist at the University of Pittsburgh, said that he voted “on gut feeling rather than really truly serious data.” The comment exemplified how much we still don’t know regarding the need for boosters, thanks in large part to the CDC’s failure to comprehensively track breakthrough cases in the U.S.

Still, there are a few major facts that we have learned since the FDA and CDC discussions on Pfizer boosters that took place a couple of weeks ago. Here’s my summary of what we’ve learned—and what we still don’t know.

What we’ve learned since the Pfizer discussion:

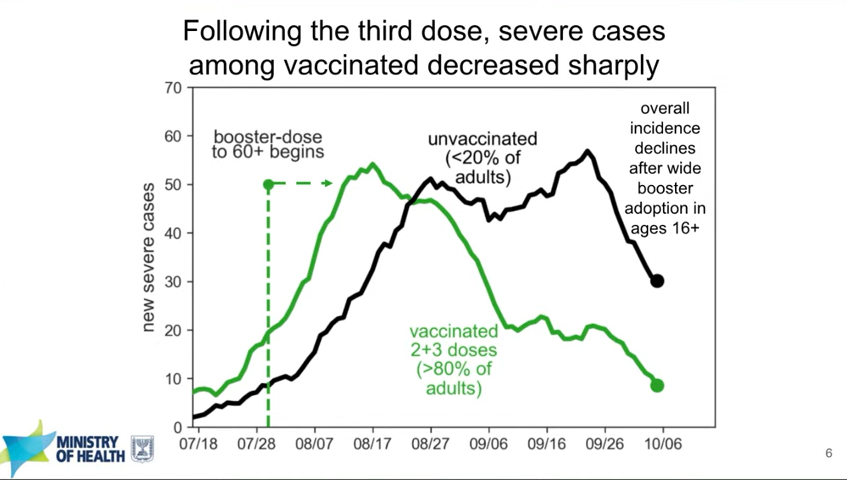

Israel’s booster rollout continues to align with falling case numbers. On Thursday, representatives from the Israeli national health agency presented data on their booster shot rollout—which, again, is using Pfizer vaccines. The vast majority of seniors in Israel have now received a third dose, and over 50% of other age groups have as well. According to the Israeli scientists, this booster rollout both decreased the risk of severe COVID-19 disease for older adults and helped to curb the country’s Delta-induced case wave, causing even unvaccinated adults to have a decreased risk of COVID-19.

You can read more about Israel’s booster campaign in this paper, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in early October. It’s worth noting, however, that Delta is known to spur both case increases and decreases in cycles that can be somewhat unpredictable—and may not be exactly linked to vaccination. So, I personally take the Israeli claims that boosters stopped their case wave with a grain of salt.

Decreased vaccine effectiveness against infection may be tied more to Delta and behavioral factors than “waning antibodies.” This week, the New York State Department of Health (DOH) announced results from a large study of vaccine effectiveness which is, from what I’ve seen, the first of its kind in the U.S. The New York DOH used state databases on COVID-19 vaccinations, tests, and hospitalizations to examine vaccine effectiveness against both infection and hospitalization in summer 2021, when Delta spread rapidly through the state.

They found that vaccine effectiveness against infection did decline over the summer. But the declines occurred similarly for all age groups, vaccine types, and vaccine timing (i.e. which month the New Yorkers in the study received their vaccines)—suggesting that the decline in effectiveness was not tied to waning immune system protection. Rather, the effectiveness decline correlated well with Delta’s rise in the state. It also correlated with reduced safety behaviors, like the lifting of New York’s indoor mask mandate and the reopening of various businesses.

Vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization declined for older adults, but remained at very high levels for New Yorkers under age 65, the study found. Here’s what lead author Dr. Eli Rosenberg said in a statement:

The findings of our study support the need for boosters in older people in particular, and we encourage them to seek out a booster shot from their health care provider, pharmacy or mass vaccination site. We saw limited evidence of decline in effectiveness against severe disease for people ages 18 to 64 years old. While we did observe early declines in effectiveness against infections for this age group, this appears to have leveled off when the Delta variant became the predominant strain in New York. Together, this suggests that ongoing waning protection may be less of a current concern for adults younger than 65 years.

I was surprised that this study didn’t come up in the FDA advisory committee meetings this week, and will be curious to see if it’s cited in future booster shot discussions. The study does align, however, with the committee’s decision against recommending booster shots for all adults over age 18 who received Moderna vaccines.

Johnson & Johnson vaccine recipients appear to need boosters more than mRNA vaccine recipients. On Friday, presentations from both J&J representatives and FDA scientists made a clear case for giving J&J vaccine recipients a second dose of this adenovirus vaccine. In one 30,000-patient study, patients who received a second J&J shot two months after their first shot saw their vaccine efficacy (against symptomatic infection) rise from 74% to 94%.

Interestingly, unlike the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, a J&J shot’s ability to protect against coronavirus infection appears relatively stable over time. However, a booster shot can make this vaccine more effective—especially against variants. Despite arguments from J&J representatives that their vaccine’s second dose should come six months after the first dose, the FDA advisory committee voted to recommend second J&J shots just two months after the first dose, for all adults over age 18.

It’s worth noting that this vaccine regimen might effectively change J&J’s product from a one-shot vaccine to a two-shot vaccine. STAT’s Helen Branswell and Matthew Herper go into the situation more in their liveblog.

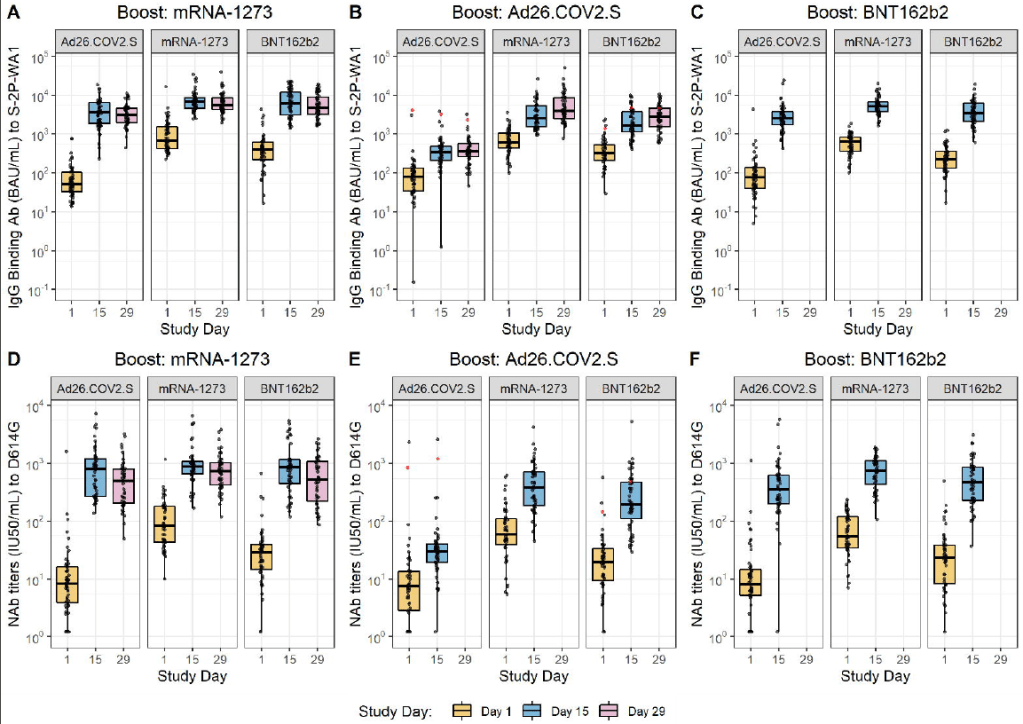

Mixing and matching vaccines is a strong strategy for boosting immunity, especially if one of the vaccines involved uses mRNA technology. This week, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) released a highly anticipated study (posted as a preprint) on mix-and-match vaccine regimens. The NIH researchers essentially tested every possible booster combination among the three vaccines that have been authorized in the U.S. Before and after vaccination, the researchers took blood samples and tested for antibodies that would protect against the coronavirus.

In short, the NIH study found that all three vaccines—Pfizer, Moderna, and J&J—will provide a clear antibody boost to people who have received any other vaccine. But the mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) provide bigger benefits, both in the form of higher baseline antibody levels (after two shots) and a higher boost. The best combination was a J&J vaccine initially, followed by a Moderna booster, Dr. Katelyn Jetelina notes in a Your Local Epidemiologist summary of the study.

The booster regimens also appeared to be safe, with limited side effects. But this was a relatively small study, including about 450 people. In their discussion on Friday afternoon, the FDA advisory committee members said that they would be very likely to authorize mix-and-match vaccine regimens after seeing more safety data.

Moderna and J&J boosters appear to be safe, with similar side effects to second shots. Safety data from Moderna’s and J&J’s clinical trials of their booster shots, along with data from the NIH mix-and-match study, indicate that the additional doses cause similar side effects to first and second doses. After a booster, most recipients had a sore arm, fatigue, and other relatively minor side effects.

And here’s what we still don’t know:

Which medical conditions, occupations, and other settings confer higher breakthrough case risk? I wrote about this issue in detail in September. The U.S. continues to have little-to-no data on breakthrough case risk by specific population group, whether that’s groups of people with a specific medical condition or occupation. This data gap persists, even though U.S. researchers have some avenues for breakthrough risk analysis at their disposal (see: this post from last week).

This lack of data came up in FDA advisory committee discussions on Thursday. An FDA representative was unable to cite any evidence that people in specific occupational settings are at a higher risk for breakthrough cases.

Are there any rare vaccine side effects that may occur after breakthrough doses? When I covered the FDA advisory committee meeting on Pfizer boosters, I noted that Pfizer’s clinical trial of these shots included just 306 participants—providing the committee members with very limited data on rare adverse events, like myocarditis. Well, Moderna’s clinical trial of its booster shots was even smaller: just 171 people. J&J had a larger clinical trial, including over 9,000 people.

These trials and the NIH mix-and-match study indicated that booster shots cause similar side effects to first and second shots, as I noted above. But few clinical trials are large enough to catch very rare (yet more serious) side effects like myocarditis and blood clots. (In J&J’s case, blood clots occur roughly twice for every million doses administered.) Federal officials will carefully watch for any side effects that show up when the U.S.’s booster rollout begins for Moderna and J&J.

How do antibody levels correlate to protection against COVID-19, and what other aspects of the immune system are involved? The NIH mix-and-match study focused on measuring antibody levels in vaccine recipients’ blood, as did other booster shot trials. While it may sound impressive to say, for example, “J&J recipients had a 76-fold increase in neutralizing antibodies after receiving a Moderna booster,” we don’t actually know how this corresponds to protection against COVID-19 infection, severe disease, and death.

Some experts—including a couple of those on the FDA advisory committee—have said that discussions focusing on antibodies distract from other types of immunity, like the memory cells that retain information about a virus long after antibody levels have fallen. More research is needed to tie various immune system measurements to real-world protection against the coronavirus.

What needs to happen at the FDA for mix-and-match vaccination to be authorized? One challenge now facing the FDA is, the federal agency has clear evidence that mix-and-match vaccine regimens are effective—but it does not have a traditional regulatory pathway to follow in authorizing these regimens. Typically, a company applies for FDA authorization of its specific product. And right now, no vaccine company wants to apply for authorization of a regimen that would involve people getting a different product from the one that brings this company profit.

So, how will the FDA move forward? There are a couple of options, like the CDC approving mix-and-match boosters directly. See this article for more info.

Finally: I can’t end this post without acknowledging that, as we discuss booster shots in the U.S., millions of people in low-income countries have yet to even receive their first doses. Many countries in Africa have under 1% of their populations vaccinated, according to the Bloomberg tracker. While the Biden administration has pledged to donate doses abroad, boosters take up airtime in expert discussions and in the media—including in this publication. Boosters distract from discussions of what it will take to vaccinate the world, which is our true way out of the pandemic.