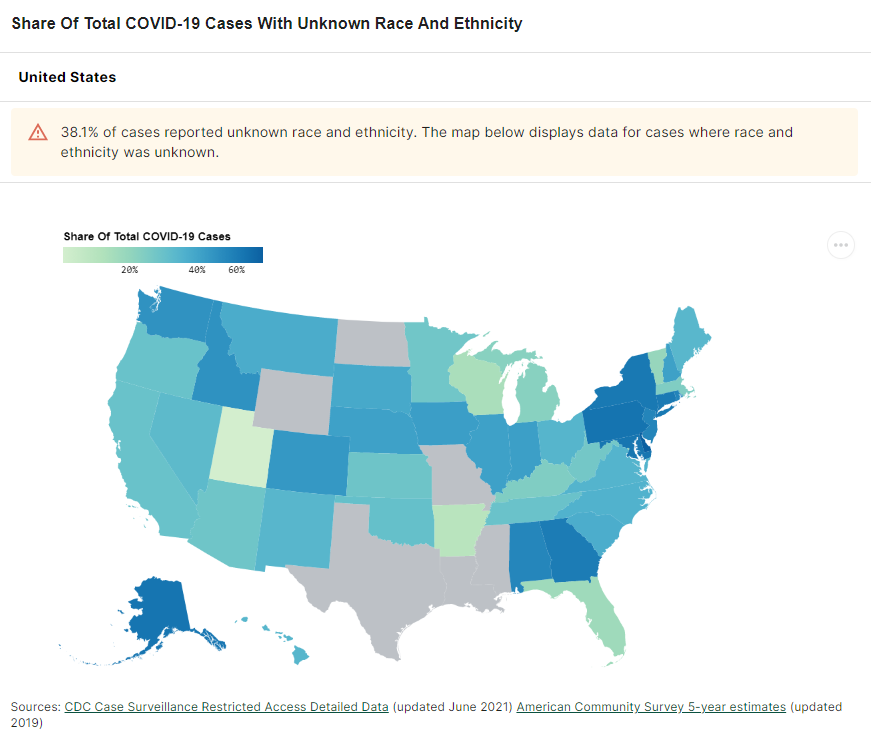

Two weeks ago, a major new COVID-19 data source came on the scene: the Health Equity Tracker, developed by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine.

This tracker incorporates data from the CDC, the Census, and other sources to provide comprehensive information on which communities have been hit hardest by COVID-19—and why they are more vulnerable. Notably, it is currently the only place where you can find COVID-19 race/ethnicity case data at the county level.

I featured this tracker in the CDD the week it launched, but I wanted to dig more into this unique, highly valuable resource. A couple of days ago, I got to do that by talking to Josh Zarrabi, senior software engineer at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute—and a fellow former volunteer with yours truly at the COVID Tracking Project.

Zarrabi has only been working on the Health Equity Tracker for a couple of months, but he was able to share many insights into how the tracker was designed and how journalists and researchers might use it to look for stories. We talked about the challenges of obtaining good health data broken out by race/ethnicity, communicating data gaps, and more.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: Give me the backstory on the Health Equity Tracker, like how it got started, how the different stakeholders got involved.

Josh Zarrabi: At the beginning of the pandemic, the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine saw the lack of good COVID data in the country, and especially the lack of racial data. The COVID Tracking Project kind-of tried to solve that as well with the Racial Data Tracker.

Morehouse wanted to do something similar. And so they applied for a Google.org grant… After about nine months, the tracker just got released. It went through a couple of different iterations, but what it is now is, it’s a general health equity tracker, so it tracks a couple of different determinants of health. And it really has a focus on equity between races and amplifying marginalized races as much as possible.

Probably the most innovative thing it does is, it shows COVID rates by race down to the county level. We think that’s relatively hard to find anywhere else. (Editor’s note: It is basically impossible to find anywhere else.) So that’s probably like the main feature that it has that people care about, but it does track other health metrics. We also have poverty, health insurance, and we try to track diabetes and COPD, but there’s not great data on that, unfortunately, in the United States. We’re planning to add more metrics in the future.

BL: How does this project build on the COVID Racial Data Tracker? And I know, like APM has a tracker for COVID deaths by race. And there are a couple other similar projects. So what is this one doing that is taking it to the next level?

JZ: A couple of things. We’re using the CDC restricted dataset. Basically what the dataset looks like is, it’s like a very large CSV file where every single line is an individual COVID case. So we’re able to break it down basically however we want. So we were able to break that down to the county level, state level and national level.

And what we do is we allow you to compare that [COVID rates] to rates of poverty, and rates of health insurance in different counties. We think that’s pretty innovative, and we’re gonna allow you to compare it to other things in the future. So that’s one thing that we do. And I mean, the second thing that I would say is like, probably makes us stand out the most I would say is our real focus on racial equity, and showing where the data gaps are and how that affects health equity. So what you’ll notice, if you go to our website, we very prominently display the amount of unknown…

BL: Yeah, I was gonna ask you about that, because I know the COVID Racial Data Project had similar unknown displays. Why is it so important to be highlighting those unknowns? And what do you want people to really be taking away from those red flag notes?

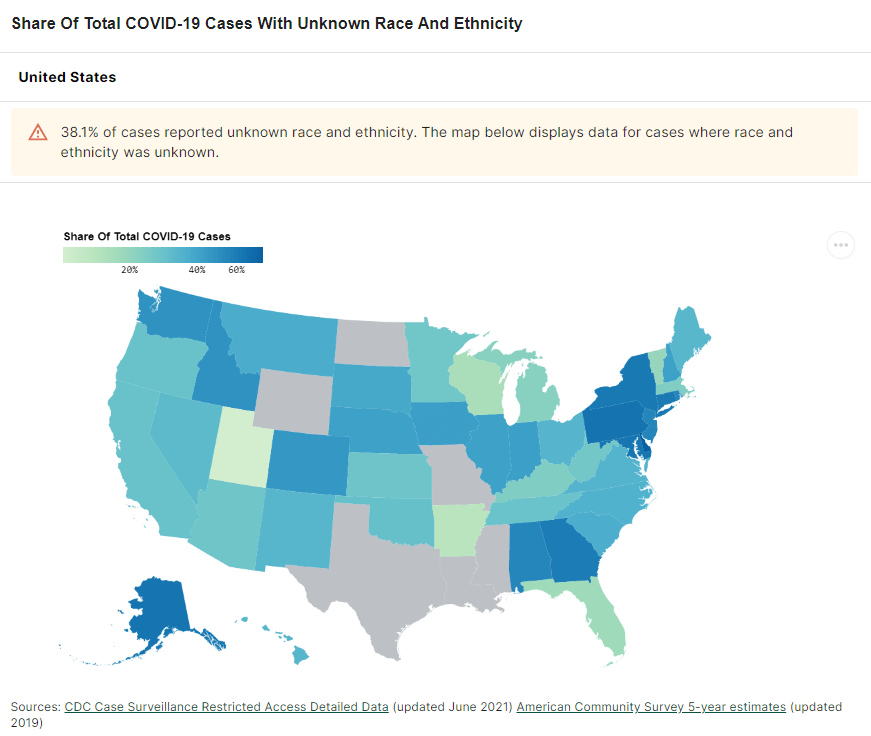

JZ: We really try to do our best to display the data in context as much as possible. First of all, the most important thing, I think, is just showing the high percentage of unknown race and ethnicity of COVID cases in the United States. For something like 40% of cases, we don’t know the race and ethnicity of the person who had COVID.

We want people to really think about that when they look at, for example, you’ll notice that it looks like Black Americans are affected to the exact level of their population. Black Americans look like 12% of the population and 11% of cases. But we don’t know the race of 40% of people who have COVID. And so we really wanted people to think about that when they look at these numbers. And it’s the same for American Indian/Alaskan Native populations. It doesn’t look like they’re that heavily affected in the United States. But that’s why we allow you to break down into the county level, where race is not being reported. And so we really want people to look and say, like, oh, wow, like in Atlanta, 60% of cases are not being counted for race and ethnicity.

We’re not doing any extrapolation. We’re not multiplying, we’re not like trying to guess the races of unknowns, or anything like that. We really want people to think about that, when they’re saying like, oh, wow, it looks like Native American people are not really heavily affected by COVID. It’s like, no, we just don’t know. We don’t know their races, or those people are just not being reported properly by the health agencies.

And if you look at places that have high percentages of Black Americans and high percentages of American Indian/Alaskan Natives, you’ll see that those places are the same places that are not reporting the race and ethnicity of the people who had COVID.

We had a team of about 20 health equity experts advising us throughout the entire project. That’s where those red flags that you see come from. It’s explaining, for example, if you look into deaths for Native American and Alaska Natives, there’s an article about how a lot of American Indian/Alaskan Native people who died are not, are improperly categorized racially, and they’re often categorized as white. And so we have that kind of stuff to really try to put the numbers in context.

We were only able to do that, because we had this large team of racial equity experts and health equity experts advising us throughout the entire time. And so we really had diverse representation on the project as we were building it, and people who really knew what they were talking about.

BL: What can public health agencies and also researchers and journalists do to push for better data in this area?

JZ: The good thing is we are seeing [data completion] get better over time. And so we’ve seen, for example, the percentage of race and ethnicity for cases improved from about 50% to about 60% over the last couple of months.

And, I mean, really, all you can do is—it’s really a thing that goes down to the county level. So, everybody’s just got to call their county representatives. I’d be like, hey, could you please report the race and ethnicity of the county’s COVID cases to the CDC? Unfortunately, a lot of that work might be too late, because [data were submitted months ago]. But we have seen it get better. And so we’re hoping that, you know, these health agencies are able to do the work and really, like, properly report these cases to the CDC…

BL: ‘Cause a lot of it comes from the case identification point, where if you’re not asking on your testing form, what race are you, then you just might not have that information. Or you might be, like, guessing and getting it wrong or something, right?

JZ: Yeah, there’s guessing. There’s two different categories of unknown cases—there’s unknown and there’s missing. The vast majority of these cases have filled out unknown [in the line file], which means that the person who’s filling out the data form literally puts “unknown” as the race. We don’t really know exactly what that means in every case. But it could be they didn’t ask, it could be the person didn’t feel comfortable saying it, just said, “I don’t want to tell you my race.” Or it could just be that they just didn’t make an effort to figure out what their race is.

(Editor’s note: For more on the difficulties of collecting COVID-19 race data, I recommend this article by Caroline Chen at ProPublica.)

BL: Do you have a sense of how that 60% known cases compares to what the COVID Racial Data Tracker had in compiling from the states?

JZ: Yeah, I think the COVID Racial Data Tracker was a bit higher [in how many cases had known race/ethnicity]. But the thing is, as far as I understand, the COVID Racial Data Tracker was using aggregate numbers.

BL: We were looking at the states and then kind-of like, synthesizing their data to the best of our ability, which was pretty challenging because every state had slightly different race and ethnicity categories. There were some states that had almost no unknown cases, but there were some where almost all cases or almost all deaths were unknown. New York, I don’t know if they ever started reporting COVID cases by race.

JZ: They do to the CDC, I don’t think they report—

BL: They don’t report it on their own, state public health site.

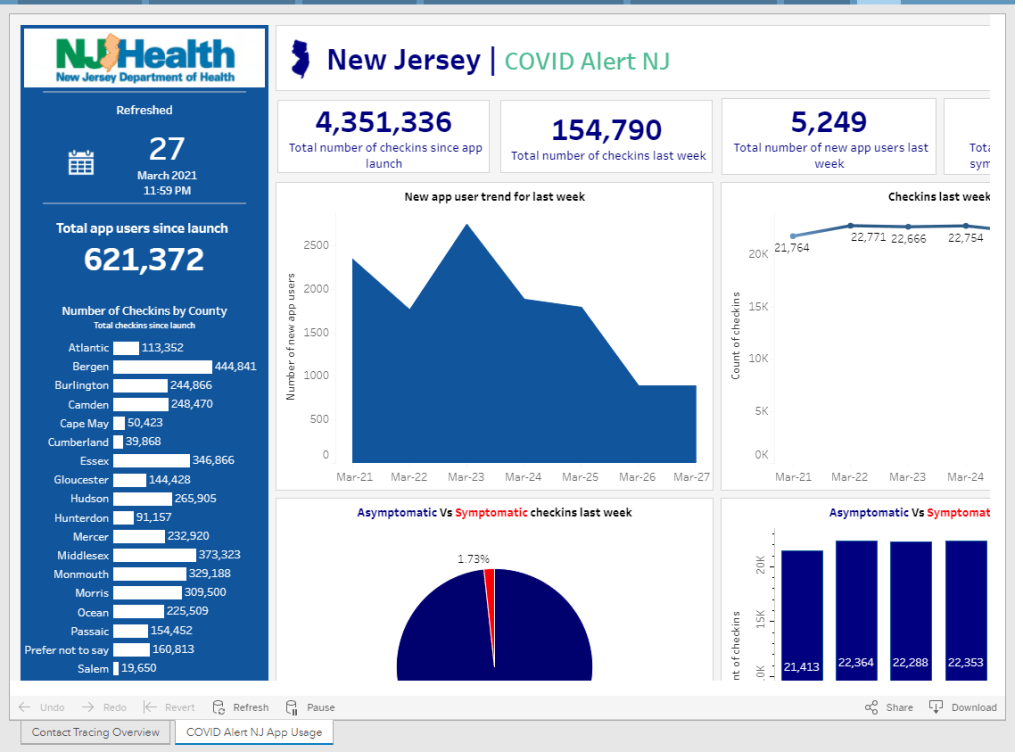

JZ: Let me actually check that… Yeah, so New York is not great. They have a 60% unknown rate. [Race and ethnicity is only reported to the CDC for 40% of cases.] Not great. Actually, New York City is pretty good. But the rest of New York State is not doing a good job reporting the race and ethnicity of cases.

BL: Because I’ve gotten tested here, I know that New York City is good about collecting that [race and ethnicity] from everybody.

JZ: I was one of those cases in New York City, actually. When [I got called by a contact tracer], I was kind of chatting with them about this. They asked me about my race—I actually became a probable case for COVID, like, the day after I started this job. And [NYC Health] called me, they were like, “What’s your race?” I was like, “Oh, that’s kind of funny, I just started working on this racial data project.” And—this is totally anecdotal. But she told me, most people just refuse to report their race.

And then for deaths… 40% of COVID deaths in New York state, they don’t know the race, which is not great. New York is not good compared to the rest of the states. It’s one of the worst states for unknowns.

BL: Could you tell me more about the process of getting the [restricted] case surveillance data from the CDC and how you’ve been using that?

JZ: The process of getting it’s not that hard. You just apply, and then they give you access to a GitHub repo, and then you can just use it. Using the data itself is pretty hard because the data files are so large. We were lucky enough to have a team of Google engineers working on this project, they wrote a bunch of Python scripts that analyze the data and aggregate it in a way that the CDC isn’t doing.

The reason why they restrict the use is because it’s line-by-line data. [Each line is a case.] And the CDC does suppress some of the data because they think it would make those cases identifiable. Still, you’re not allowed to just, like, release the data into the wild, because they want to know who else has track of it. So, we wrote some Python to aggregate the data, in exactly the way you see on the website. We aggregate it to the amount of cases, deaths and hospitalizations per county, per race, essentially.

The CDC has been extremely helpful, like, we’ve had a couple of meetings with them. We think we were one of the heaviest users of the data at the beginning, because we pointed out a couple of problems with the data that they actually fixed. So, that’s cool.

BL: That’s good to hear that they were responsive.

JZ: Yeah, definitely. We meet with them every couple of weeks. They’re really good partners in this.

BL: And they update that [case surveillance] dataset once a month?

JZ: They started doing it every two weeks now. Every other Monday, they update the dataset.

BL: Could you talk more about the feature of the tracker that lets you compare COVID to other health conditions and insurance rates? I thought that was really unique and worth highlighting.

JZ: We wanted to really provide the [COVID] numbers in context. And so that’s one way that we thought that we could do that and really show how… These numbers don’t happen, like a high rate of COVID for race doesn’t happen in a vacuum. There are political determinants of health.

For example, you’ll see everywhere that Hispanic Americans are just by far the most impacted by COVID case-wise. In California especially. And we provide those numbers in context—Hispanic Americans are also much less likely to be insured than white Americans, for example, and much more likely to be in poverty. And, you know, it’s not a crazy surprise that they would also be more likely to have contracted COVID at some point.

[The comparison feature] was a way that we thought, we would just allow people to really view numbers in context and get a better understanding of what the political situation is on the ground with where these high numbers are happening.

BL: What are the next conditions that you want to add to the tracker?

JZ: I want to be careful, because we can’t make any promises. But we’re talking about adding smoking rates, maybe. [The challenge is] where we can find data that we can aggregate correctly.

BL: Right. Are you looking specifically for data that’s county level as opposed to state level?

JZ: Hopefully… It depends. I was pretty surprised by the lack of quality in, for example, COPD and diabetes data, where like, if you look at [the dataset], like it’s state level—but in most states, there’s not a statistical significance for most races.

BL: Wow.

JZ: For example, we use the BRFSS survey. [The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.] It’s a CDC survey. And as far as we can tell, it’s the gold standard for diabetes [data] in the country.

And if you look at, say, diabetes, for most states… There’s only, like, four states where Asian people are statistically significant in the survey to make any sort of guess about how many people have diabetes, which is pretty atrocious. But that [data source] is the best we could do, you know. Ideally, we would like to find places that do go down to the county level, but it’s hard.

For as paltry as the COVID data is, it’s much better than—as far as I’ve seen, like, the fact that there’s like a line-by-line database that the CDC provides, that you can really make all these breakdowns of, is a huge step ahead [compared to other health data]. I’m not like a data expert on this kind of stuff, I’ve just been working on this project for two and a half months. But as far as I’ve seen, that’s what the situation is.

BL: Yeah, I mean, that kind of lines up with what I have seen as well. And I bet a lot of it is a case where, like, a journalist could FOIA [the data] from a county or from a state. But that’s not the same as getting something that is comprehensive, line-by-line, from the CDC.

JZ: And we [the Satcher institute] don’t want to be a data collection agency, like the COVID Tracking Project or the New York Times is. I mean, we want this to be a sustainable project. And the COVID Tracking Project was not a sustainable project.

BL: Yeah, totally. I was there doing the [data entry] shifts twice a week, that’s not something we could have done forever.

JZ: Yeah, I was there, too. I always think, like, the COVID Tracking Project could only exist when there’s an army of unemployed people who are too afraid to leave their house.

BL: And volunteers who were like, yeah, sure, I’ll do this on my evenings and weekends.

JZ: Who, you know, you don’t want to leave, you’re too afraid to go, like talk to people. You want to stay home in front of your computer all day, and feel useful.

I’m sure you could find all the diabetes data by going to county and state health department websites, but it’s too much work. So we really want everything to come from federal sources, basically, that’s our goal.

BL: How are you finding that people have used the tracker so far? Like, do you know of any research projects that folks are doing?

JZ: We released it a couple weeks ago, and we haven’t really heard of any yet… But we hope people are looking at it. And we have a couple of meetings lined up with some interesting research groups and stuff like that. So hopefully, they’ll like it.

BL: Are there any specific statistics or comparisons or anything else you found in working on it that you would want to see explored further? Are there any stories that you want to see come out of it?

JZ: The high rates of unknown data in a lot of places, that really needs to be looked into. Because it’s just hard to make any conclusions about what’s going on if—I mean, in some states like New York, over 50% of cases are unknown. That’s a huge problem. And that’s definitely something that needs to be looked into, like, why that’s happening. And if there’s anything that can be done to change that [unknown rate.] The reason why I do think that it can get better is because the COVID Tracking Project racial data had higher completeness rates. And so they [the states] probably do know the races of people who got sick, but they’re just not reporting it for whatever reason.

And for me, something that’s really stuck out was the extremely high rates of COVID for Hispanic and Latino people, especially in California. If you look at them and compare them to white rates, it’s, like, the exact opposite pattern. So it kind of does look like Hispanic and Latino people were kind-of shielding white people from getting COVID, if you compare the numbers. That’s something I would look into, too, like, why that happened.

(Editor’s note: This story from The Mercury News goes into how the Bay Area’s COVID-19 response heightened disparities for the region’s Hispanic/Latino population.)

BL: And another question along the same lines, is there a specific function or aspect of the tracker that you would encourage people to check out?

JZ: The unknowns. Just, like, look into your county and see what percentage of cases in your county have reported race and ethnicity at all. I think you can really see how good of a job your county has done at reporting that data. I know I was kind-of shocked by that rate for the county like I grew up in, like, I know that they have the resources to [report more data], but they’re just not doing a very good job.

BL: How would you say this experience with tracking COVID cases might impact the world of public health data going forward, specifically health equity data, and how do you see the tracker project playing a role in that?

JZ: We really want this project to show the importance of tracking racial health data down to the county level or even lower than that. County is the best we can do right now, but we’d love to see city level or something like that. And again, I kind-of said this before—as much as was missing for the COVID data, it’s still better than the data that there is for most other diseases and other determinants of health. So we would like to see, like, more things able to be filled out on the tracker. We would like to be able to get more granular on more different determinants of health, so that we can see, for example, how poverty impacts health, or a lack of health insurance, or how diabetes and COVID are related down to the county level. You can’t really do that right now…

We want people to see that, A, there’s a lot of data missing. But B, even with the data that we have, we can see that there’s like a huge problem. And so we would like to be able to fill out the data more to really get a better picture of what’s going on. If we can see there’s a problem, we can make better policy to help and make these disparities not as stark.