The Delta variant is now dominant in the U.S., but our high vaccination rates still put us in a much better position than the rest of the world—which is facing the super-contagious variant largely unprotected.

Let’s look at how the U.S.’s situation compares:

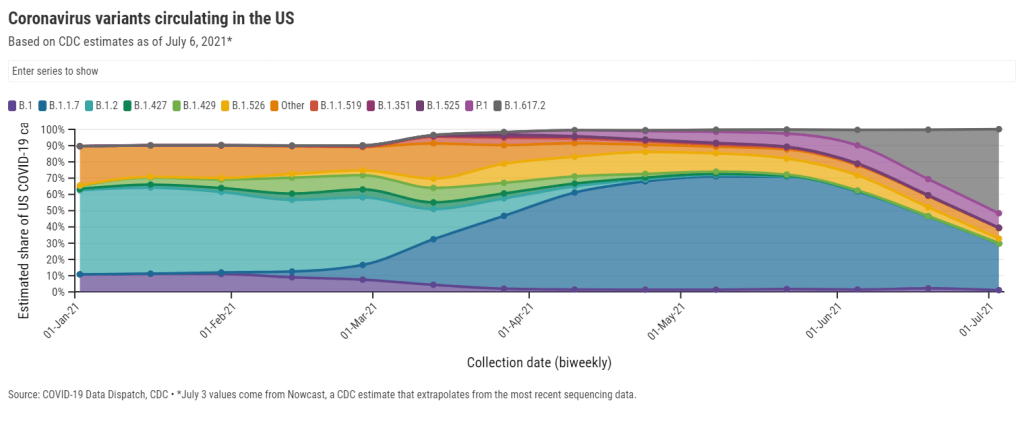

U.S.: Delta now causes 52% of new cases, according to the latest Nowcast estimate from the CDC. (This estimate is pegged to July 3, so we can assume the true number is higher now.) It has outcompeted other concerning variants here, including Alpha/B.1.1.7 (now at 29%), Gamma/P.1 (now at 9%), and the New York City and California variants (all well under 5%). And Delta has taken hold in unvaccinated parts of the country, especially the Midwest and Mountain West.

Israel and the U.K.: Both of these countries—lauded for their successful vaccination campaigns—are seeing Delta spikes. Research from Israel has shown that, while the mRNA vaccines are still very good at protecting against Delta-caused severe COVID-19, these vaccines are not as effective against Delta-caused infection. As a result, public health experts who previously said that 70% vaccination could confer herd immunity are now calling for higher goals.

Japan: The Tokyo Olympics will no longer allow spectators after Japan declared a state of emergency. The country is seeing another spike in infections connected to the Delta variant, and just over a quarter of the population has received a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. I argued in a recent CDD issue that, if spectators are allowed, the Olympics could turn into a superspreading event.

Australia: Several major cities are on lockdown in the face of a new, Delta-caused surge following a party where every single unvaccinated attendee was infected. Unlike other large countries that faced significant outbreaks, Australia has successfully used lockdowns to keep COVID-19 out: the country has under 1,000 deaths total. But the lockdown strategy has diminished incentives for Australians to get vaccinated; under 5% of the population has received a shot. Will lockdowns work against Delta, or does Australia need more shots now?

India: Delta was first identified in India, tied to a massive surge in the country earlier this spring. Now, India has also become the site of a Delta mutation, unofficially called “Delta Plus.” This new variant has an extra spike protein mutation; it may be even more transmissible and even better at invading people’s immune systems than the original Delta, though scientists are still investigating. India continues to see tens of thousands of new cases every day.

Africa: Across this continent, countries are seeing their highest case numbers yet; more than 20 countries are experiencing third waves. Most African countries have fewer genetic sequencing resources than the U.S. and other wealthier nations, but the data we do have are shocking: former CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden reported that, in Uganda, Delta was detected in 97% of case samples. Meanwhile, vaccine delivery to these countries is behind schedule—Nature reports that many people in African countries and other low-income nations will not get their shots until 2023.

South America: This continent is also under-vaccinated, and is facing threats from Delta as well as Lambda, a variant detected in Peru last year. While Lambda is not as fast-spreading as other variants, it has become the dominant variant in Peru and has been identified in at least 29 other countries. Peru has the highest COVID-19 death rate in the world, and scientists are concerned that Lambda may be more fatal than other variants. Studies on this variant are currently underway.

In short: basically every region of the world right now is seeing COVID-19 spikes caused by Delta. More than 20 countries are experiencing exponential case growth, according to the WHO:

We’ve already seen more COVID-19 deaths worldwide so far in 2021 than in the entirety of 2020. Without more widespread vaccination, treatments, and testing, the numbers will only get worse.