Starting in 2024, the antiviral drug Paxlovid will be a private—and expensive—treatment for COVID-19. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced about a week ago that it’s reached a deal with Pfizer, the pharmaceutical company that produces Paxlovid, to “transition” this drug into the commercial market within the next few months. The transition will lead to Paxlovid becoming even less accessible than it is now and will exacerbate health inequities that we’ve seen with this drug.

A few days ago, news outlets reported that Pfizer will charge about $1,400 per course as the list price for Paxlovid upon this transition. This is about double the price that HHS previously paid for the drug, which was about $530 per course.

HHS previously purchased about 24 million courses of Paxlovid, of which about 17 million have been distributed and 11 million have been administered, according to the agency’s data. Under the privatization agreement, HHS will return about 8 million courses back to Pfizer, which will serve as a credit for covering continued free supply to people who have Medicare, Medicaid, or who are uninsured.

According to HHS, people who have public insurance or no health insurance should continue to receive free Paxlovid through the end of 2024. And after that, Pfizer will run a patient assistance program for people who are uninsured or underinsured. Still, the transition is likely to cause health equity issues, as people who have public insurance or no insurance will have to jump through more hoops to receive free Paxlovid under these programs, as opposed to the current situation where everyone can get it for free. We’ve all seen how chaotically this fall’s vaccine rollout went, after all.

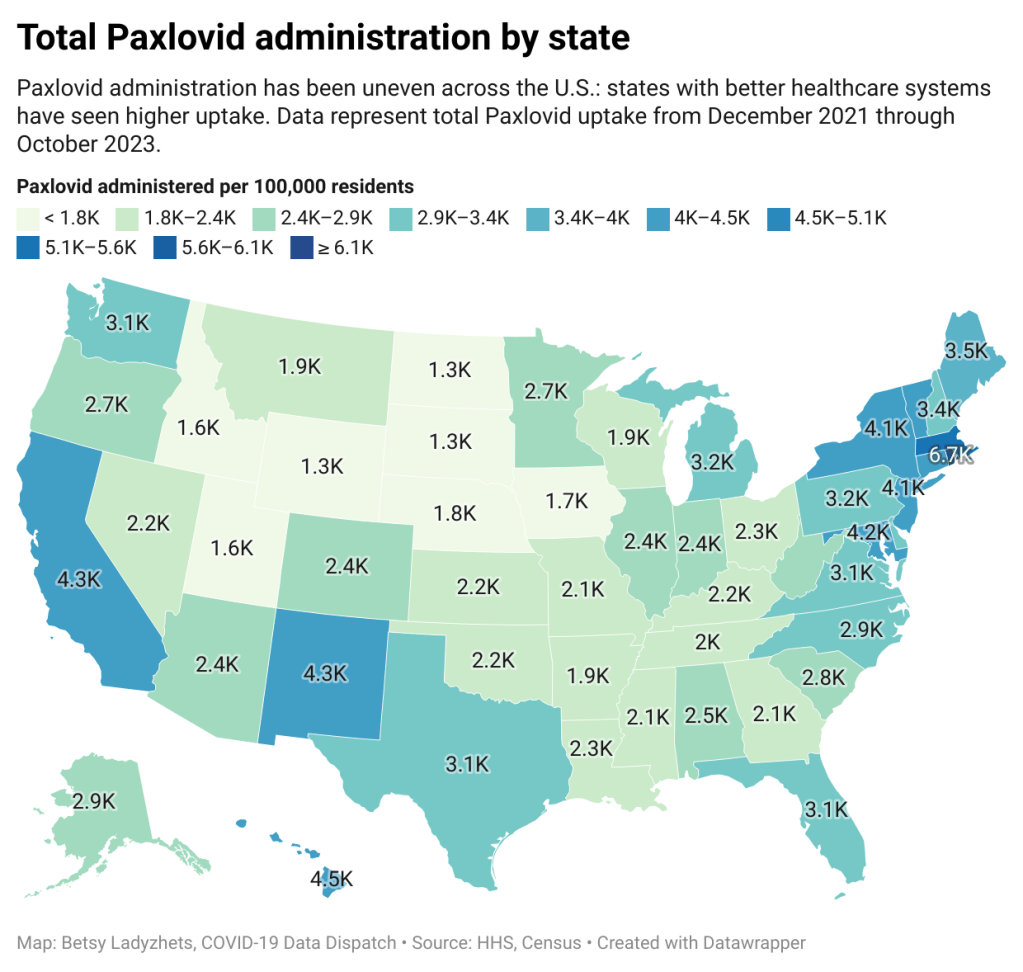

The HHS’s data for Paxlovid administration (shown above) demonstrate that states where healthcare is more easily accessible and/or where patient populations are wealthier tend to have higher rates of receiving Paxlovid over the nearly two years that it’s been available. We also know from scientific studies looking at Paxlovid that this drug has followed access issues similar to the COVID-19 vaccines and tests.

Considering these prior patterns, combined with the increasing price, it unfortunately seems like a foregone conclusion that Paxlovid will get harder to access in 2024. This will be a huge issue for preventing severe disease and death from COVID-19 as well as limiting risks of Long COVID, which research suggests Paxlovid can do as well.

If you are a reader who’s had a hard time getting Paxlovid, or if you want to share more comments or questions on this issue, please reach out.