In January, COVAX set a goal that many global health advocates considered modest: delivering 2.3 billion vaccine doses to low- and middle-income countries by the end of 2021. COVAX (or COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) is an initiative to provide equitable access to vaccines; its leadership includes the United Nations, the World Health Organization (WHO), and other organizations.

Despite COVAX’s broad support, the initiative has revised its vaccine delivery projections down again and again this year. Now, the initiative is saying it’ll deliver just 800 million vaccine doses by the end of 2021, according to the Washington Post, and only about 600 million had been delivered by early December.

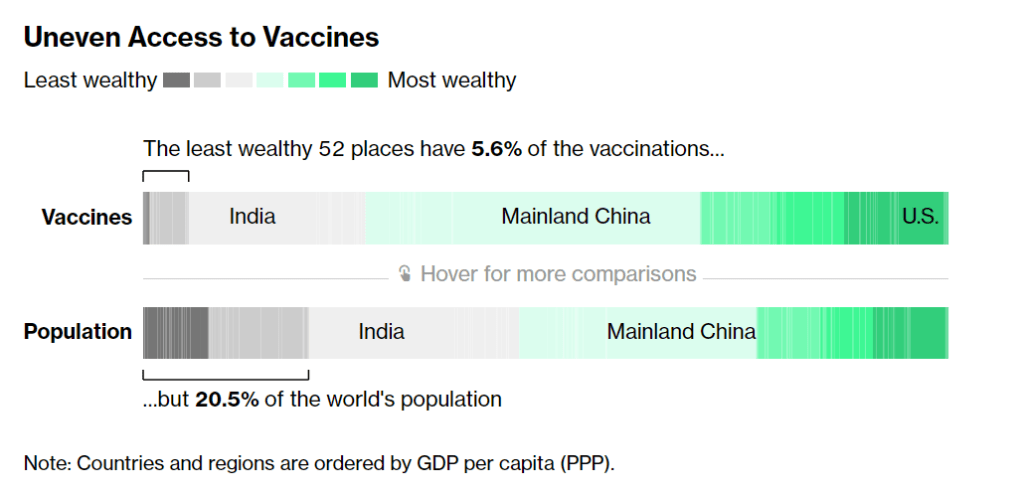

Considering that most COVID-19 vaccines are two-dose series—and boosters will likely be necessary to combat Omicron—those doses are just a drop in the bucket. According to Bloomberg’s vaccine tracker: “The least wealthy 52 places have 5.6% of the vaccinations, but 20.5% of the world’s population.”

Why this access gap? Many scientists and advocates in low- and middle-income nations blame vaccine manufacturers and rich countries like the U.S., I found when I reported a story on this topic for Popular Science.

“We basically have artificial scarcity of vaccine doses,” says Robbie Silverman, a vaccine advocate at Oxfam America. The pharmaceutical companies control “where doses are produced, where they’re sold, and at what price.” The world’s vaccine supply is thus limited by contracts signed by a small number of big companies; and many of those contracts, [Fatima Hassan, health advocate from South Africa] says, are kept secret behind non-disclosure agreements.

While rich countries claimed to support COVAX, the Washington Post reports, “they also placed advance orders with vaccine manufacturers before COVAX could raise enough money to do so.” This practice pushed COVAX to the back of the vaccine line—and then, when rich countries decided they needed booster shots, that pushed COVAX to the back of the line again. India’s spring 2021 surge didn’t help either, as the country blocked vaccine supplies produced at the Serum Institute of India from being exported to other nations.

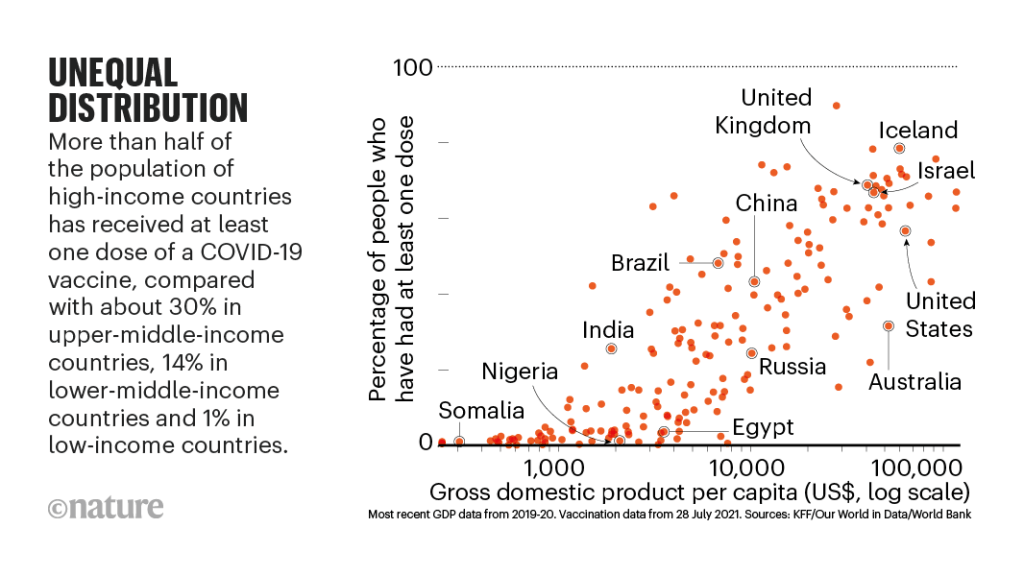

According to Our World in Data, low-income nations have administered about 60 million doses total, while high-income nations have administered more than 300 million booster shots. At times this winter, there were more booster shots administered daily than first and second doses in low-income countries.

Even taking booster shots into consideration, there should be enough vaccine supplies produced by the end of this year to vaccinate 40% of the world’s population by the end of this year, meeting WHO targets, according to STAT News’ Olivia Goldhill. The world is on track to manufacture about 11 billion vaccines in total this year, Goldhill reports, while about 850 million doses are needed to get all countries to a 40% vaccination benchmark.

But again, rich countries pose a problem: the countries currently focused on administering booster shots have stockpiled hundreds of millions of doses, and are unwilling to send their stockpiles abroad. From STAT News:

“That number can be redistributed from what high-income countries expect to have by the end of this year. So it’s not an overall supply challenge,” said [Krishna Udayakumar, founding director of Duke’s Global Health Innovation Center]. “It’s very much an allocation challenge, as well as getting high income countries more and more comfortable that they don’t need to hold on to hundreds of millions of doses, for contingencies.”

The vaccine shortage for low-income countries is less than the surplus vaccines within the G7 countries and the European Union, according to separate analyses from both Duke and Airfinity, a life sciences analytics firm that is tracking vaccine distribution.

While leaders in the U.S., the U.K., and other nations with large stockpiles maintain that they can both administer booster shots at home and send doses for primary series shots abroad, their true priorities are clear. The U.S., for example, has pledged to donate 1.2 billion doses to other countries, but about 320 million—under one-third—of those doses have been shipped out so far.

Another challenge is the type of vaccines being used in wealthy nations, as opposed to low- and middle-income nations. Wealthy nations have been particularly eager to horde Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines, which are more effective against Omicron and other variants of concern. On the other hand, many low-income nations have relied on Sputnik, CoronaVac, and other vaccines which are less effective.

“We’re now entering an era of second-class vaccines for second-class people,” Peter Maybarduk, director at the DC-based nonprofit Public Citizen, told me in October, discussing these differences in vaccine effectiveness. As Omicron spreads around the world, this concern is only growing.

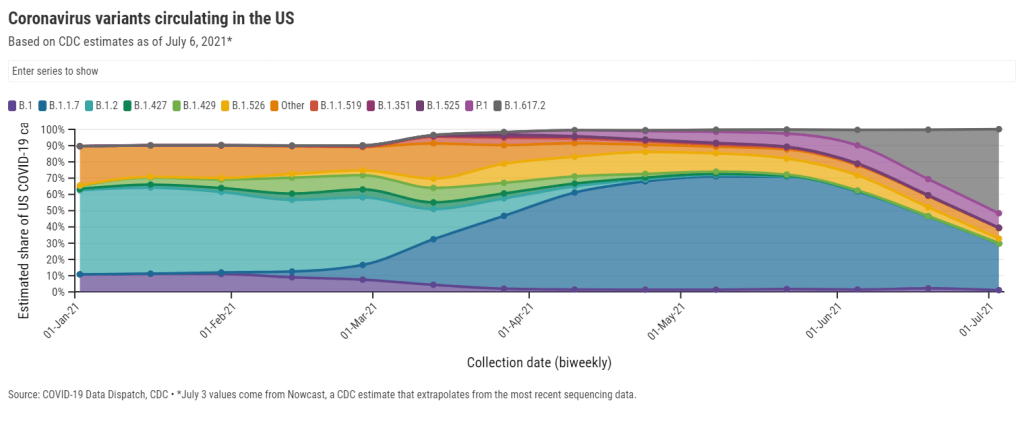

The more the coronavirus spreads across the world, particularly in regions with less immunity from vaccines, the more it can mutate and create new variants. Delta and Omicron provide clear examples, demonstrating the need to vaccinate the world in 2022.

And there are some reasons to hope that this goal may be feasible. COVAX’s global supply forecast shows major jumps in vaccine supplies in the first three months of 2022. At the same time, vaccine companies are increasing their production capacity, and donations from the U.S. and other countries are expected to kick in. In South Africa, an mRNA vaccine hub is working to train African companies to manufacture COVID-19 vaccines similar to Pfizer and Moderna’s, without violating patents.

Still, additional variants—and the need for additional booster shots—could be a major hurdle, as vaccine companies continue to prioritize wealthy nations. These companies continue to refuse to share their intellectual property with other manufacturers, even as they make patents for COVID-19 antiviral drugs widely available. And, once vaccines are delivered, getting them from shipments into arms will be a challenge.

More international data