Two years into the pandemic, we now know some basic truisms about the coronavirus. For example: outdoor events are always safer than indoor events; older age is the most significant risk factor for severe symptoms; hospitalization trends typically follow case trends by a couple of weeks; and whenever Europe has a new surge, the U.S. is likely to also see a surge in the next month or so.

That last truism is particularly relevant right now, because Europe is experiencing a new surge. Cases are increasing in the U.K., Germany, the Netherlands, and many other countries. The new surge is likely due to European leaders’ decisions to end all COVID-19 safety measures in their countries, combined with the rise of Omicron sublineage BA.2.

As BA.2 prevalence increases here in the U.S.—and our leaders also end safety measures—we seem poised to follow in Europe’s footsteps once again. But a BA.2 surge is likely to look different from the intense Omicron surge that we experienced in December and January, in part because of leftover immunity from that Omicron surge.

Let’s go over what we know about BA.2, and what might happen in the next few weeks.

What is BA.2?

It’s important to note that this isn’t a new variant, at least not compared to the original Omicron strain. As I noted in a FAQ post about this strain back in January, South African scientists who originally characterized Omicron in November 2021 identified three sub-lineages: BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3.

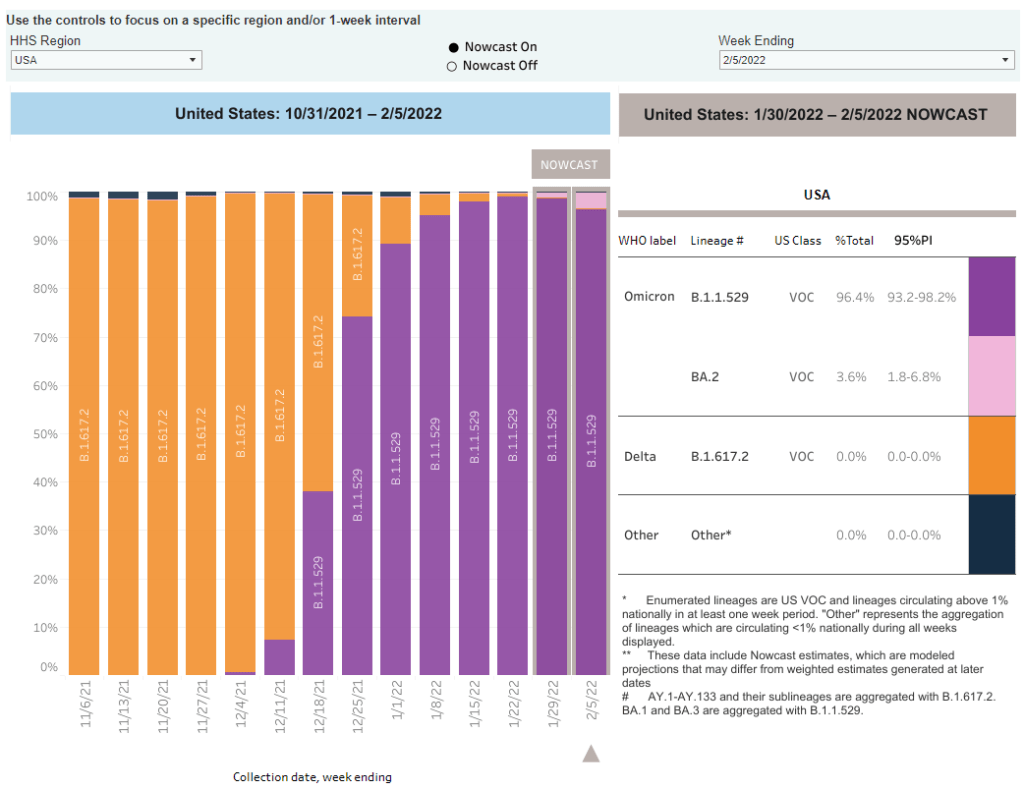

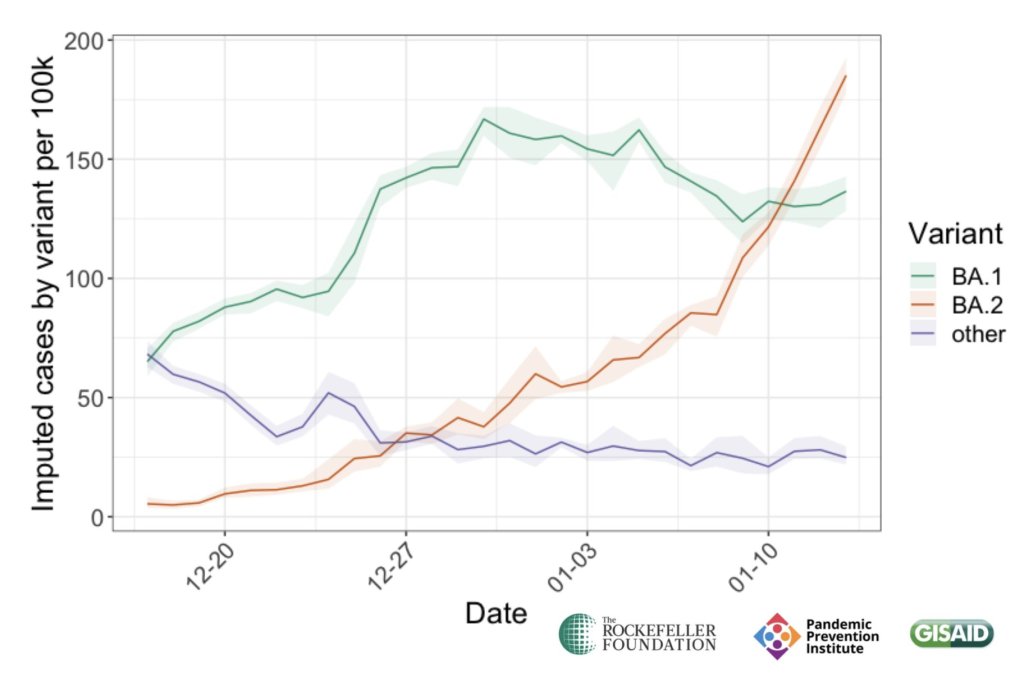

BA.1 spread rapidly through the world, driving the surge that we experienced here in the U.S. in December through February. But BA.2, it turns out, is actually more transmissible than BA.1—allowing it to now outcompete that strain and contribute to case increases in countries that already faced major BA.1 surges.

How does BA.2 differ from BA.1, or original Omicron?

The main difference between these two strains is that BA.2 is more contagious: scientists estimate that BA.2 is about 30% more transmissible than other Omicron strains, if not more. (Note that this is a smaller difference than Omicron’s advantage over Delta and other earlier variants.)

In a recent report, the U.K. Health Security Agency estimated that someone infected with BA.2 would infect about 13.6% of their households and 5.3% of contacts outside of their households, compared to 10.7% of households and 4.2% outside contacts for other Omicron strains. The modest difference between these rates demonstrates why BA.2 is not outcompeting other Omicron strains as quickly as Omicron outcompeted Delta a couple of months ago.

Another notable feature of BA.2 is that, unlike BA.1, it can’t be identified with a PCR test. BA.1 has a mutation called S drop-out, which causes a special signal in PCR test results, allowing the variant to be flagged without sequencing; BA.2 doesn’t have this mutation. To be clear, a PCR test will still return a positive result for someone who is infected with BA.2—it’ll just take an additional sequencing step to identify that they have this particular strain.

Finally, one major challenge during the Omicron BA.1 surge has been that two of the three monoclonal antibody treatments used in the U.S. did not work well for people infected with Omicron. BA.2 may exacerbate this challenge, as some studies have suggested that the third treatment—called sotrovimab—continued working against BA.1, but may not hold up against BA.2. Luckily though, Eli Lilly (which developed one of the treatments that failed for BA.1) has produced an updated monoclonal antibody cocktail that does work for both Omicron strains.

How is BA.2 similar to BA.1, or original Omicron?

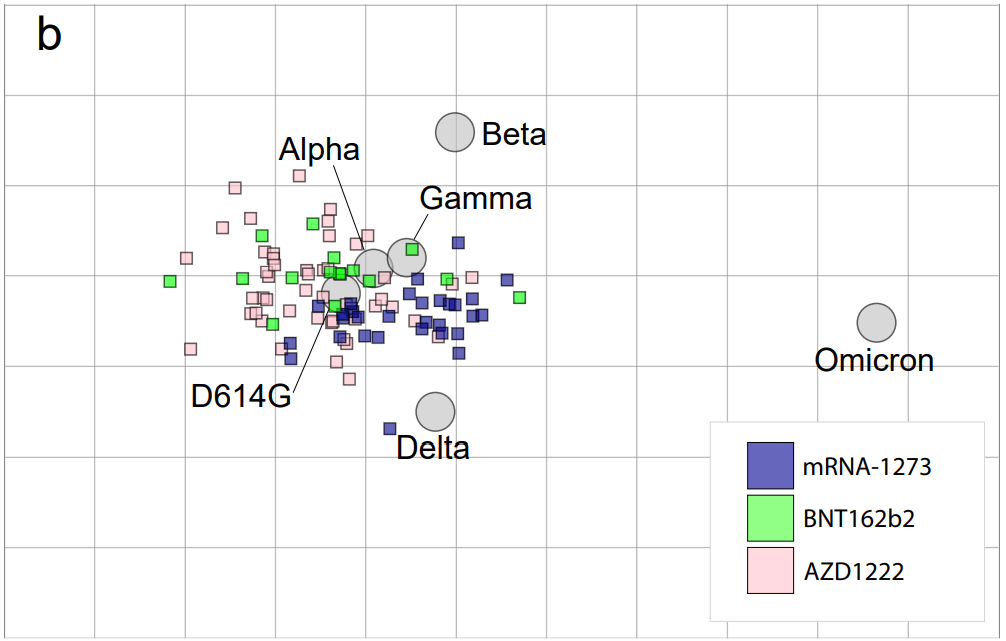

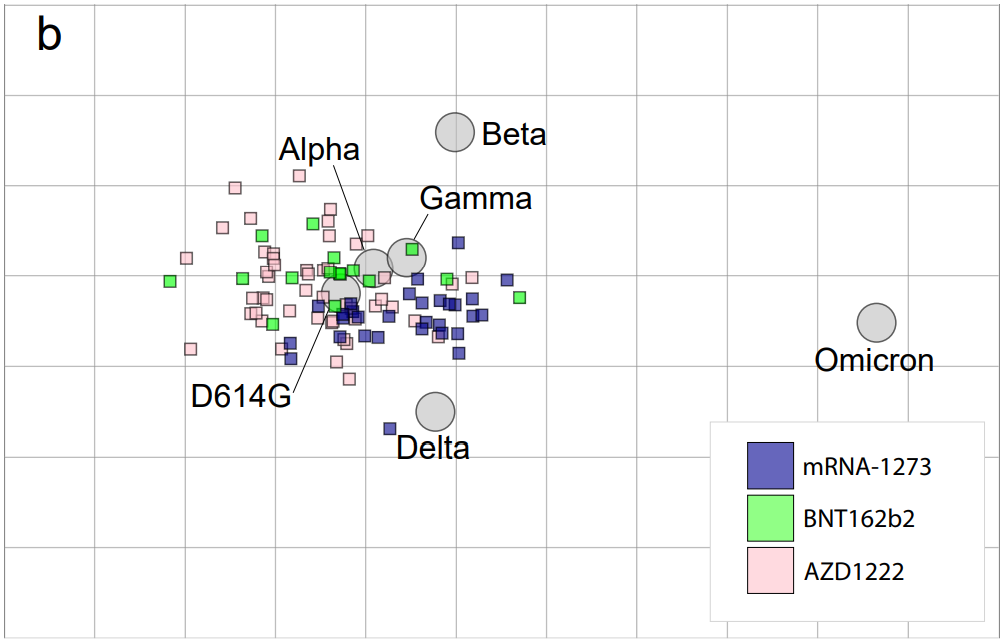

Two major pieces of good news here: 1) our existing COVID-19 vaccines work similarly well against BA.2 as they do against BA.1, and 2) prior infection with BA.1 seems to be protective against infection with BA.2.

Essentially, studies are showing that the two strains are close enough in their genetic profiles that antibodies from a BA.1 infection will provide some immunity against a BA.2 infection. And the same thing goes for vaccination, at least when it comes to protection against severe disease. A recent CDC study showed that, even during the Omicron surge, COVID-19 patients who had received three vaccine doses were far less likely to require mechanical ventilation or die from the disease than those who weren’t vaccinated.

There’s a flip side to this, though: for both BA.1 and BA.2, prior infection with a previous variant is not very protective against an Omicron infection. CDC seroprevalence data suggest that between 40% and 45% of Americans got infected with BA.1 during the winter surge; this means the remaining 55% to 60% of the population is susceptible to BA.2. Vaccines protect against severe disease and death from BA.2, but they don’t protect against BA.2 infection to the degree that they did against past variants.

BA.2 and BA.1 are also similar in their severity. Both strains are less likely to cause severe disease than Delta; BA.1 had a 59% lower risk of hospital admission and 69% lower risk of death than Delta in the U.K., according to a new paper published this week in the Lancet.

It’s important to remember, however, that Delta was actually more severe than other variants that preceded it. As a result, “Omicron is about as mild/severe as early 2020 SARSCoV2,” wrote computational biologist Francois Balloux in his Twitter thread (referring to both BA.1 and BA.2).

What are the warning signs for a BA.2 surge in the U.S.?

First of all, many U.S. experts consider case increases in Europe to be an early indicator of increases in the U.S. As I said at the top of the post, Europe is seeing a surge right now, and many of the countries reporting case increases have estimated over 50% of their cases are caused by BA.2.

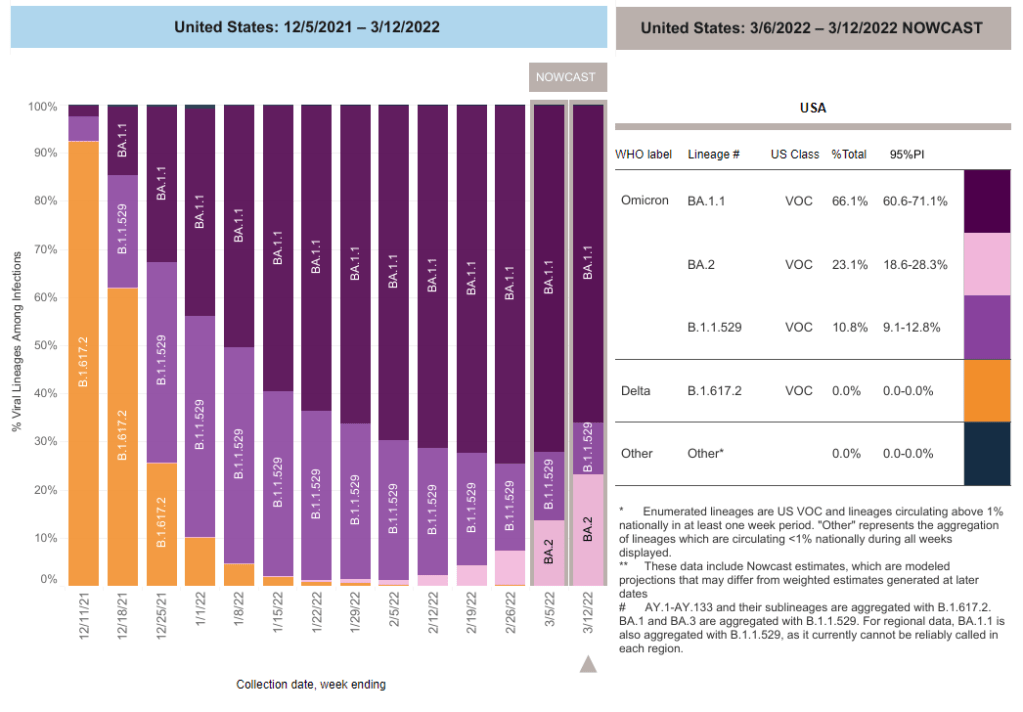

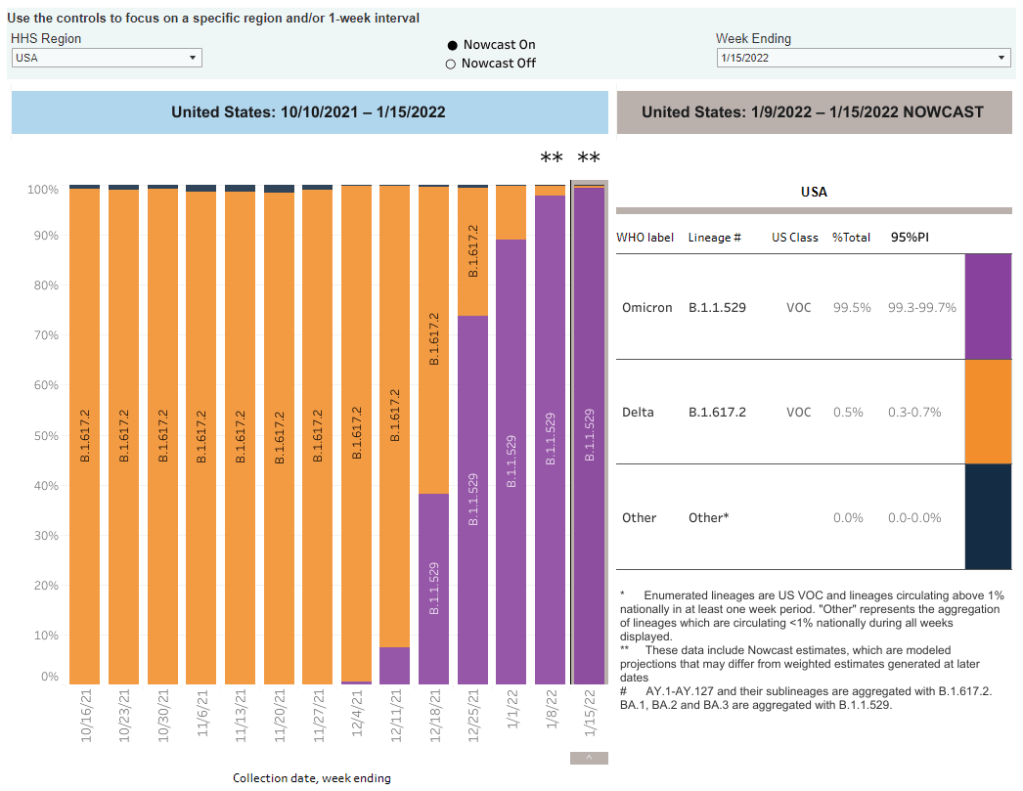

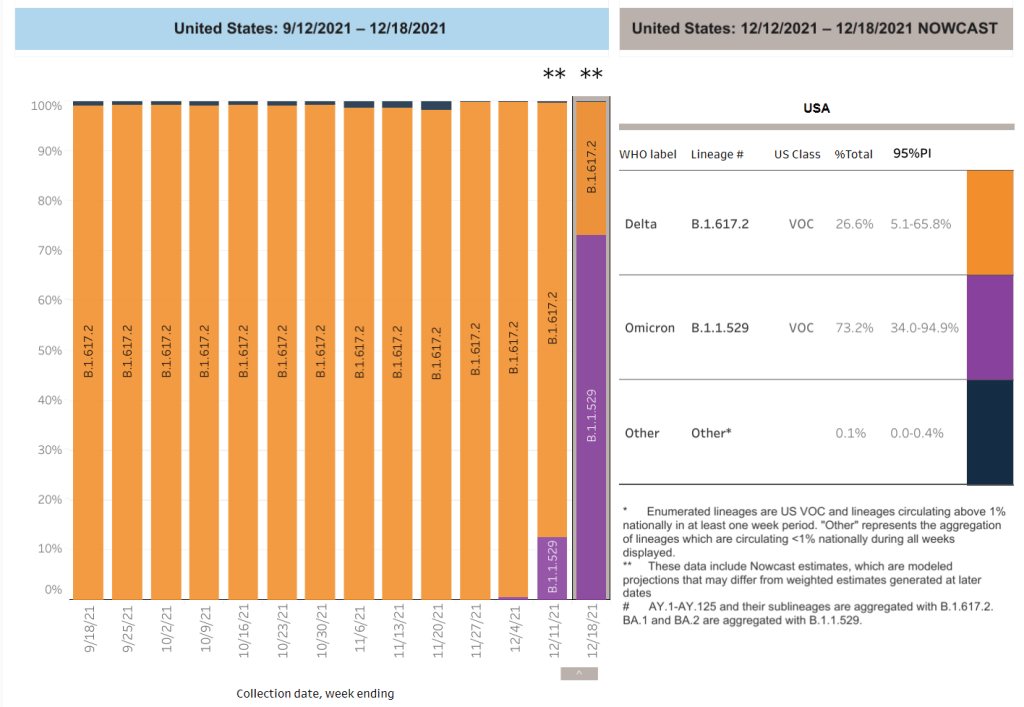

In the U.S., our BA.2 levels are lower: the CDC’s most recent estimates suggested that BA.2 was causing about 23% of new cases nationwide as of March 12. If BA.2 continues growing at the same rate we’ve seen in recent weeks, we have one or two more weeks before this variant hits 50% prevalence in the U.S.

“The tipping point seems to be right around 50%,” Keri Althoff, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told CNN. “That’s when we really start to see that variant flex its power in the population” as far as showing its severity.

At the same time, several Asian countries are also seeing major BA.2 surges at the moment. For example, Hong Kong was able to deal with early Omicron cases earlier in the winter, former COVID Tracking Project lead Erin Kissane pointed out in her Calm Covid newsletter; but now, the territory is facing a terrible BA.2 wave, driving what is now the world’s highest case fatality rate.

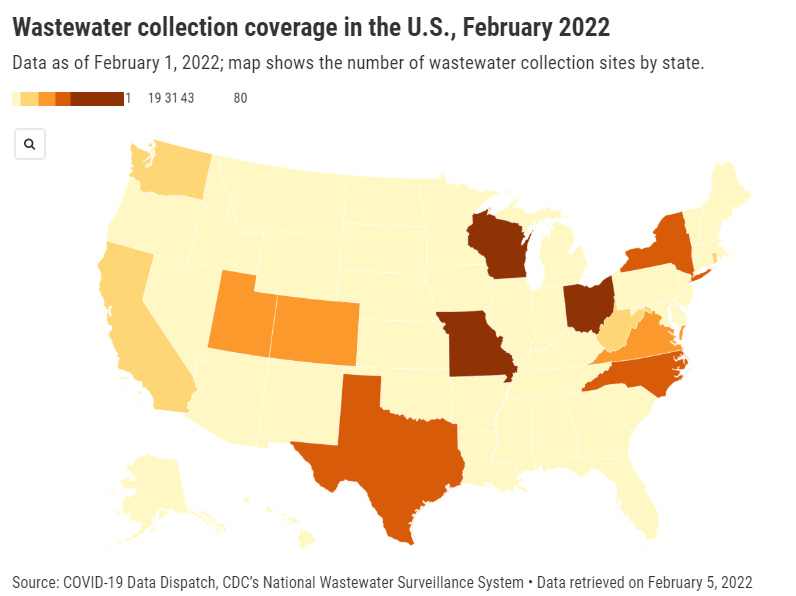

Here in the U.S., we’re also seeing warning signals in the form of rising coronavirus levels in wastewater. (Wastewater is considered an early indicator for surges, because coronavirus material often shows up in sewer systems before people begin to experience symptoms or get tested.) About one-third of sewershed collection sites in the CDC’s wastewater monitoring network are reporting increased virus prevalence in the two-week period ending March 15.

The CDC wastewater data must be interpreted cautiously, however, as this surveillance network is biased towards states like Missouri and Ohio, which have over 50 collection sites included in the national network. 12 states still do not have any collection sites in the network at all, while 23 states have fewer than 10. This recent Bloomberg article includes more context on interpreting wastewater data.

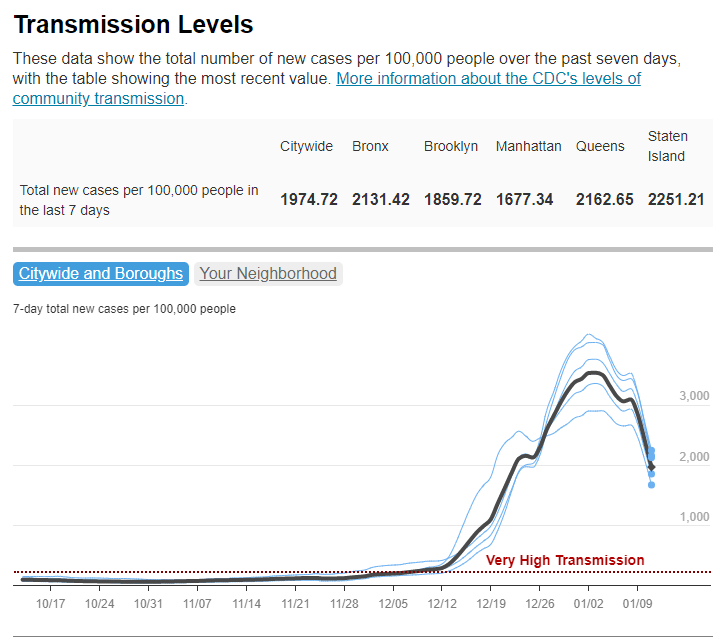

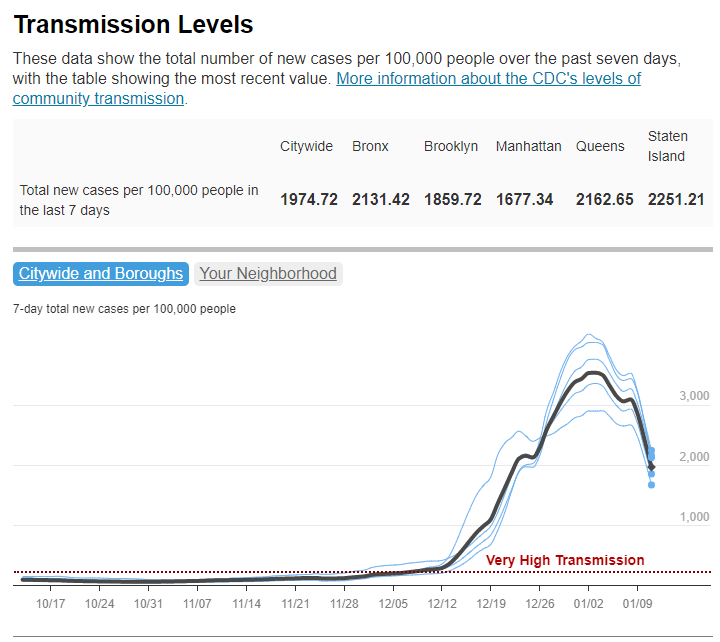

New York City is one place that’s reporting increased viral levels in wastewater, at the same time as the city health department reports that case numbers have plateaued—or may even be ticking up. An excellent time to loosen all mask and vaccination requirements, am I right?

What might a BA.2 surge in the U.S. look like?

Between the warning signals from Europe and the newly-lax safety measures throughout the U.S., it seems very likely that we will see a BA.2 surge in the coming weeks. The bigger question, though, is this surge’s severity: to what extent will it cause severe disease and death?

As I mentioned above, estimates suggest that about 40% to 45% of Americans have some Omicron antibodies from an infection earlier in the winter. At the same time, about 65% of the population is fully vaccinated and 45% of those fully vaccinated have received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

That’s a lot of people who are protected against severe COVID-19 symptoms, if they get infected with BA.2. But the U.S. has lower vaccination coverage than other countries, particularly when it comes to boosters. For example, in the U.K., 86% of eligible people are fully vaccinated and 67% are boosted, according to CNN. These lower vaccination rates contributed to the U.S.’s high mortality rate during the Omicron surge compared to other wealthy countries.

While the vaccines offer great protection, the U.S. appears to have given up on many other COVID-19 safety measures, like masks, social distancing, and limits on in-person gatherings. Without reinstating some of these measures, we would essentially be left without any tools to slow down the spread of BA.2; and even if some states and cities put safety measures in place, they’ll likely face more pushback now than they did in earlier surges.

To quote from Kissane’s newsletter:

In practical terms, with work and school happening in-person and without high-filtration (or any) masks or serious ventilation requirements in the US and most of Europe, governments in North America and Europe have made increased covid exposure essentially mandatory for most citizens.

I want to emphasize that for most vaccinated people, this increased risk probably won’t be a huge deal even if BA.2 causes a new case surge—they’ve either already racked up enough immunity to fight off BA.2 or they’ll be sick for a week.

One big caveat to this, though: we don’t have great data yet on how Omicron (or BA.2 specifically) might contribute to Long COVID rates; collecting data on this condition is very challenging and takes a lot of time. Studies suggest that vaccination reduces an individual’s risk of long-term symptoms if they get infected, but it does not eliminate this risk.

What can you do to prepare for this potential surge?

Here are a few things that I’m doing to prepare for a potential BA.2 surge in the coming weeks:

- Promoting vaccination—particularly booster shots—to family members and friends.

- Stocking up on good-quality masks (i.e. N95s and KN95s) and rapid tests. (Reminder, order a new round of free tests from covidtests.gov if you haven’t yet!)

- Researching my options for COVID-19 treatments (antiviral pills and monoclonal antibodies) in the event that I get infected.

- Getting tested frequently, particularly before attending indoor events (such as gathering with a few other friends, or going out to a movie theater.)

- Watching wastewater and case trends in my area, and preparing to cut down on riskier behaviors if(/when) cases start rising.

As always, if you have any COVID-19 questions (about BA.2 or otherwise) that you’d like me to address, please reach out.