- Free at-home tests from the federal government: The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Postal Service are restarting their program offering free COVID-19 rapid, at-home tests. Starting tomorrow, every U.S. household will be able to order four more tests at covidtests.gov. HHS also announced that it’s buying about 200 million further rapid tests from major manufacturers, paying a total of $600 million to twelve companies. Of course, four tests per household is pretty minimal when you consider all the exposures people are likely to have this fall and winter—but it’s still helpful to see the federal government acknowledge a continued need for testing.

- New grants support Long COVID clinics: The HHS and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also announced a new grant program for clinics focused on Long COVID, aiming to make care for this condition more broadly accessible to underserved communities. Nine clinics across the country have received $1 million each, with the opportunity to renew their grants over the next five years. (At least, that’s my interpretation of the HHS press release, which says $45 million in total is allocated to this program.) This is a pretty significant announcement, as it marks the first time that the federal government is specifically funding Long COVID care; funding has previously gone to RECOVER and other research projects.

- CDC announces new disease modeling network: One more federal announcement: the CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics has established a new program to improve the country’s disease surveillance, working with research institutions across the country. The CDC has awarded $262.5 million of funding to the thirteen institutions participating in this program, which it’s calling the Outbreak Analytics and Disease Modeling Network. These institutions will develop new surveillance tools, test them in small-scale projects, and scale up the successful options to broader public health systems. For more context on the CDC’s forecasting center, see my story for FiveThirtyEight last year.

- Testing wildlife for COVID-19: Speaking of surveillance: researchers at universities and public agencies are collaborating on new projects aiming to better understand how COVID-19 is spreading and evolving among wild animals. One project, at Purdue University, is focused on developing a test to better detect SARS-CoV-2 among wild animals. A second project, at Penn State University, is focused on increased monitoring, with plans to test 58 different wildlife species and identify sources of transmission from animals to humans. Both projects received grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and involve collaboration with state environmental agencies.

- Paxlovid access falls along socioeconomic lines: A new study, published this week in JAMA Network Open, examines disparities in getting Paxlovid. Researchers at the National Institutes of Health analyzed public data on Paxlovid availability as of May 2023. Counties with higher poverty, less health insurance coverage, and other markers of high socioeconomic vulnerability had significantly less access to Paxlovid than better-off counties, the scientists found. Meanwhile, a separate study (also in JAMA Network Open last week) found that Paxlovid and another antiviral treatment, made by Merck, both remain very effective in reducing severe COVID-19 symptoms. Improving access to these treatments should be a top priority for the public health system.

- Undercounted COVID-19 cases in Africa: One more study that caught my attention this week: researchers at York University in Canada developed a mathematical model to assess how many people actually got COVID-19 in 54 African countries during the first months of the pandemic. Overall, only 5% of cases in these countries were actually reported, the researchers found, with a range of reporting from 30% in Libya to under 1% in São Tomé and Príncipe. A majority of cases in these countries were asymptomatic, the models suggested, indicating many people may not have realized they were infected. The study shows “a clear need for improved reporting and surveillance systems” in African countries, the authors wrote.

Tag: disease surveillance

-

Sources and updates, September 24

-

Wastewater surveillance expands beyond COVID-19

I have a new story up this week at Science News, describing how the field of wastewater surveillance exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic and is now looking toward other public health threats.

As long-time readers know, wastewater surveillance has been one of my favorite topics to cover over the last couple of years. I’m fascinated by the potential to better understand our collective health through tracking our collective poop—and by all the challenges that this area of research faces, from navigating interdisciplinary collaborations to interpreting a very new type of data to obtaining funding for continued testing.

My story for Science News builds on other reporting I’ve done on this topic and provides a comprehensive overview of the growing wastewater surveillance field, with a particular focus on how research is now going beyond COVID-19. There’s so much potential here that, as I point out in the story, many researchers are asking not, “What can we test for?” but “What should we test for?”

Here’s the story’s introduction; go to Science News for the full article:

The future of disease tracking is going down the drain — literally. Flushed with success over detecting coronavirus in wastewater, and even specific variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, researchers are now eyeing our collective poop to monitor a wide variety of health threats.

Before the pandemic, wastewater surveillance was a smaller field, primarily focused on testing for drugs or mapping microbial ecosystems. But these researchers were tracking specific health threats in specific places — opioids in parts of Arizona, polio in Israel — and hadn’t quite realized the potential for national or global public health.

Then COVID-19 hit.

The pandemic triggered an “incredible acceleration” of wastewater science, says Adam Gushgari, an environmental engineer who before 2020 worked on testing wastewater for opioids. He now develops a range of wastewater surveillance projects for Eurofins Scientific, a global laboratory testing and research company headquartered in Luxembourg.

A subfield that was once a few handfuls of specialists has grown into more than enough scientists to pack a stadium, he says. And they come from a wide variety of fields — environmental science, analytical chemistry, microbiology, epidemiology and more — all collaborating to track the coronavirus, interpret the data and communicate results to the public. With other methods of monitoring COVID-19 on the decline, wastewater surveillance has become one of health experts’ primary sources for spotting new surges.

Hundreds of wastewater treatment plants across the United States are now part of COVID-19 testing programs, sending their data to the National Wastewater Surveillance System, or NWSS, a monitoring program launched in fall 2020 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hundreds more such testing programs have launched globally, as tracked by the COVIDPoops19 dashboard run by researchers at the University of California, Merced.

In the last year, wastewater scientists have started to consider what else could be tracked through this new infrastructure. They’re looking at seasonal diseases like the flu, recently emerging diseases like bird flu and mpox, formerly called monkeypox, as well as drug-resistant pathogens like the fungus Candida auris. The scientists are even considering how to identify entirely new threats.

Wastewater surveillance will have health impacts “far broader than COVID,” predicts Amy Kirby, a health scientist at the CDC who leads NWSS.

But there are challenges getting from promise to possible. So far, such sewage surveillance has been mostly a proof of concept, confirming data from other tracking systems. Experts are still determining how data from our poop can actually inform policy; that’s true even for COVID-19, now the poster child for this monitoring. And they face public officials wary of its value and questions over whether, now that COVID-19 health emergencies have ended, the pipeline of funding will be cut off.

This monitoring will hopefully become “one of the technologies that really evolves post-pandemic to be here to stay,” says Mariana Matus, cofounder of Biobot Analytics, a company based in Cambridge, Mass., that has tested sewage for the CDC and many other health agencies. But for that to happen, the technology needs continued buy-in from governments, research institutions and the public, Matus and other scientists say.

-

COVID source shout-out: Wastewater testing at the San Francisco airport

A few months ago, I wrote about how testing sewage from airplanes could be a valuable way to keep tabs on the coronavirus variants circulating around the world. International travel is the main way that new variants get from one country to another, so monitoring those travelers’ waste could help health officials quickly spot—and respond to—the virus’ continued mutations.

This spring, San Francisco International Airport became the first in the U.S. to actually start doing this tracking; I covered their new initiative for Science News. The airport is working with the CDC and Concentric, a biosecurity and public health team at the biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks, which already collaborates with the agency on monitoring travelers through PCR tests.

The San Francisco airport started collecting samples on April 20, and scientists at Concentric told me that they’re happy with how it’s going so far. Airport staff are collecting one sample each day, with each one representing a composite of many international flights. Parsing out the resulting data won’t be easy, but the scientists hope to learn lessons from this program that they can take to other surveillance projects.

Both scientists at Concentric and outside experts are also excited about the potential to monitor other novel pathogens through airplane waste (though the San Francisco project is focused on coronavirus variants right now). Read my Science News story for more details!

-

The federal public health emergency ends next week: What you should know

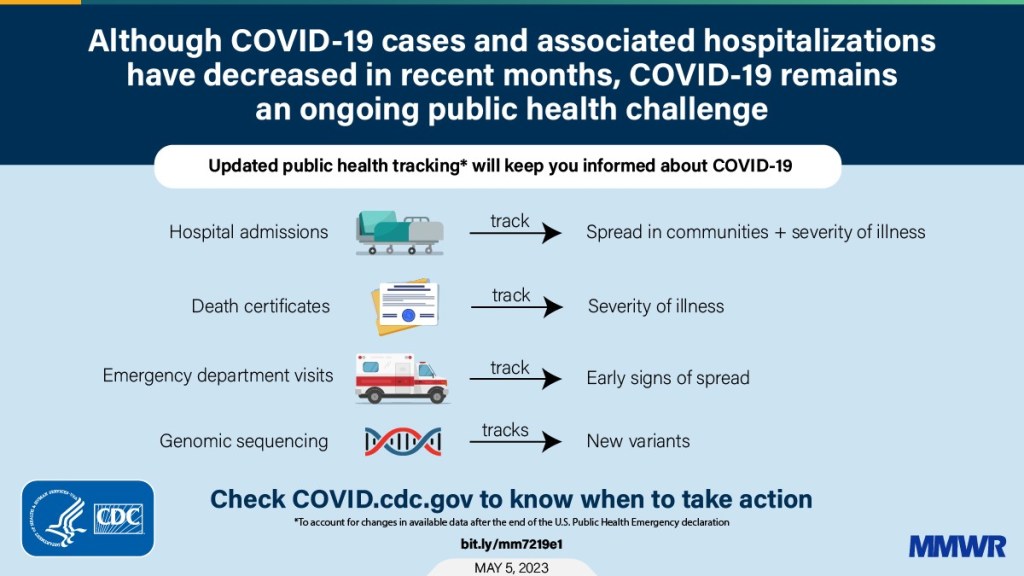

A chart from the CDC’s recent report on surveillance changes tied to the end of the federal public health emergency. We’re now less than one week out from May 11, when the federal public health emergency (or PHE) for COVID-19 will end. While this change doesn’t actually signify that COVID-19 is no longer worth worrying about, it marks a major shift in how U.S. governments will respond to the ongoing pandemic, including how the disease is tracked and what public services are available.

I’ve been writing about this a lot in the last couple of months, cataloging different aspects of the federal emergency’s end. But I thought it might be helpful for readers if I compiled all the key information in one place. This post also includes a few new insights about how COVID-19 surveillance will change after May 11, citing the latest CDC reports.

What will change overall when the PHE ends?

The ending of the PHE will lead to COVID-19 tests, treatments, vaccines, and data becoming less widely available across the U.S. It may also have broader implications for healthcare, with telehealth policies shifting, people getting kicked off of Medicaid, and other changes.

Last week, I attended a webinar about these changes hosted by the New York City Pandemic Response Institute. The webinar’s moderator, City University of New York professor Bruce Y. Lee, kicked it off with a succinct list of direct and indirect impacts of the PHE’s end. These were his main points:

- Free COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments will run out after the federal government’s supplies are exhausted. (Health experts project that this will likely happen sometime in fall 2023.) At that point, these services will get more expensive and harder to access as they transition to private healthcare markets.

- We will have fewer COVID-19 metrics (and less complete data) to rely on as the CDC and other public health agencies change their surveillance practices. More on this below.

- Many vaccination requirements are being lifted. This applies to federal government mandates as well as many from state/local governments and individual businesses.

- The FDA will phase out its Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for COVID-19 products, encouraging manufacturers to apply for full approval. (This doesn’t mean we’ll suddenly stop being able to buy at-home tests—there’s going to be a long transition process.)

- Healthcare worker shortages may get worse. During the pandemic emergency, some shifts to work requirements allowed facilities to hire more people, more easily; as these policies are phased out, some places may lose those workers.

- Millions of people will lose access to Medicaid. A federal rule tied to the PHE forbade states from kicking people off this public insurance program during the pandemic, leading to record coverage. Now, states are reevaluating who is eligible. (This process actually started in April, before the official PHE end.)

- Telehealth options may become less available. As with healthcare hiring, policies during the PHE made it easier for doctors to provide virtual care options, like video-call appointments and remote prescriptions. Some of these COVID-era rules will be rolled back, while others may become permanent.

- People with Long COVID will be further left behind, as the PHE’s end leads many people to distance themselves even more from the pandemic—even though long-haulers desperately need support. This will also affect people who are at high risk for COVID-19 and continue to take safety precautions.

- Pandemic research and response efforts may be neglected. Lee referenced the “panic and neglect” cycle for public health funding: a pattern in which governments provide resources when a crisis happens, but then fail to follow through during less dire periods. The PHE’s end will likely lead us (further) into the “neglect” part of this cycle.

How will COVID-19 data reporting change?

The CDC published two reports this week that summarize how national COVID-19 data reporting will change after May 11. One goes over the surveillance systems that the CDC will use after the PHE ends, while the other discusses how different COVID-19 metrics correlate with each other.

A lot of the information isn’t new, such as the phasing out of Community Level metrics for counties (which I covered last week). But it’s helpful to have all the details in one place. Here are a few things that stuck out to me:

- Hospital admissions will be the CDC’s primary metric for tracking trends in COVID-19 spread rather than cases. While more reliable than case counts, hospitalizations are a lagging metric—it takes typically days (or weeks) after infections go up for the increase to show up at hospitals, since people don’t seek medical care immediately. The CDC will recieve reports from hospitals at a weekly cadence, rather than daily, after May 11, likely increasing this lag and making it harder for health officials to spot new surges.

- National case counts will no longer be available as PCR labs will no longer be required to report their data to the CDC. PCR test totals and test positivity rates will also disappear for the same reason, as will the Community Levels that were determined partially by cases. The CDC will also stop reporting real(ish)-time counts of COVID-associated deaths, relying instead on death certificates.

- Deaths will be the primary metric for tracking how hard COVID-19 is hitting the U.S. The CDC will get this information from death certificates via the National Vital Statistics System. While deaths are reported with a significant lag (at least two weeks), the agency has made a lot of progress on modernizing this reporting system during the pandemic. (See this December 2021 post for more details.)

- The CDC will utilize sentinel networks and electronic health records to gain more information about COVID-19 spread. This includes the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, a network of about 450 laboratories that submit testing data to the CDC (previously established for other endemic diseases like RSV and norovirus). It also includes the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, a network of 6,300 hospitals that submit patient data to the agency.

- Variant surveillance will continue, using a combination of PCR samples and wastewater data. The CDC’s access to PCR swab samples will be seriously diminished after May 11, so it will have to work with public health labs to develop national estimates from the available samples. Wastewater will help fill in these gaps; a few wastewater testing sites already send the CDC variant data. And the CDC will continue offering tests to international travelers entering the country, for a window into global variant patterns.

- The CDC will continue tracking vaccinations, vaccine effectiveness, and vaccine safety. Vaccinations are generally tracked at the state level (every state health agency, and several large cities, have their own immunization data systems), but state agencies have established data sharing agreements with the CDC that are set to continue past May 11. The CDC will keep using its established systems for evaluating how well the vaccines work and tracking potential safety issues as well.

- Long COVID notably is not mentioned in the CDC’s reports. The agency hasn’t put much focus on tracking long-term symptoms during the first three years of the pandemic, and it appears this will continue—even though Long COVID is a severe outcome of COVID-19, just like hospitalization or death. A lack of focus on tracking Long COVID will make it easier for the CDC and other institutions to keep minimizing this condition.

On May 11, the CDC plans to relaunch its COVID-19 tracker to incorporate all of these changes. The MMWR on surveillance changes includes a list of major pages that will shift or be discontinued at this time.

Overall, the CDC will start tracking COVID-19 similar to the way it tracks other endemic diseases. Rather than attempting to count every case, it will focus on certain severe outcomes (i.e., hospitalizations and deaths) and extrapolate national patterns from a subset of healthcare facilities with easier-to-manage data practices. The main exception, I think, will be a focus on tracking potential new variants, since the coronavirus is mutating faster and more aggressively than other viruses like the flu.

What should I do to prepare for May 11?

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably concerned about how all these shifts will impact your ability to stay safe from COVID-19. Unfortunately, the CDC, like many other public agencies, is basically leaving Americans to fend for themselves with relatively little information or guidance.

But a lot of information sources (like this publication) are going to continue. Here are a few things I recommend doing this week as the PHE ends:

- Look at your state and local public health agencies to see how they’re responding to the federal shift. Some COVID-19 dashboards are getting discontinued, but many are sticking around; your local agency will likely have information that’s more tailored to you than what the CDC can offer.

- Find your nearest wastewater data source. With case counts basically going away, wastewater surveillance will be our best source for early warnings about surges. You can check the COVID-19 Data Dispatch list of wastewater dashboards and/or the COVIDPoops dashboard for sources near you.

- Stock up on at-home tests and masks. This is your last week to order free at-home/rapid tests from your insurance company if you have private insurance. It’s also a good time to buy tests and masks; many distributors are having sales right now.

- Figure out where you might get a PCR test and/or Paxlovid if needed. These services will be harder to access after May 11; if you do some logistical legwork now, you may be more prepared for when you or someone close to you gets sick. The People’s CDC has some information and links about this.

- Contact your insurance company to find out how their COVID-19 coverage policies are changing, if you have private insurance. Folks on Medicare and Medicaid: this Kaiser Family Foundation article has more details about changes for you.

- Ask people in your community how you can help. This is a confusing and isolating time for many Americans, especially people at higher risk for COVID-19. Reaching out to others and offering some info or resources (maybe even sharing this post!) could potentially go a long way.

That was a lot of information packed into one post. If you have questions about the ending PHE (or if I missed any important details), please email me or leave a comment below—and I’ll try to answer in next week’s issue.

More about federal data

-

At-home tests, wastewater: COVID-19 testing after the public health emergency ends

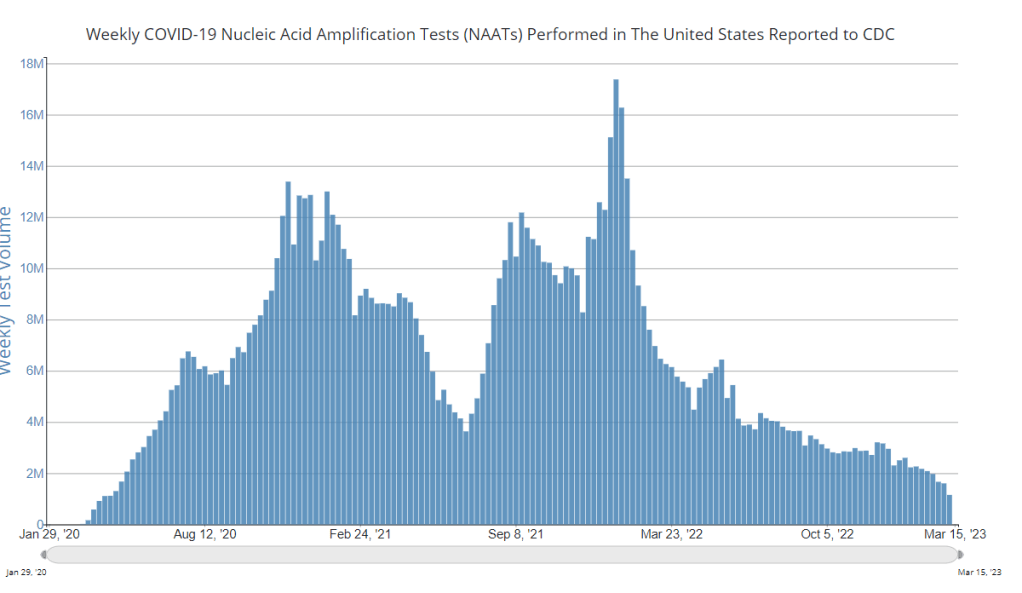

Nationwide, fewer people are getting lab-based COVID-19 tests now than at any time since the start of the pandemic. Chart via the CDC. When the public health emergency ends this spring, COVID-19 testing is going to move further in two separate directions: rapid, at-home tests at the individual level, and wastewater testing at the community level.

That was my main takeaway from an online event last Tuesday, hosted by Arizona State University and the State and Territory Alliance for Testing. This event discussed the future of COVID-19 testing following the public health emergency, with speakers including regulatory experts, health officials from state agencies, and executives from diagnostic companies.

“The purpose of testing has shifted” from earlier in the pandemic, said Dr. Thomas Tsai, the White House’s COVID-19 testing coordinator, in opening remarks at the event. Public health agencies previously used tests to monitor COVID-19 in their communities and direct contact-tracing efforts; now, individual tests are mostly used for diagnosing people, and the resulting data are widely considered to be a major undercount of true cases.

While the speakers largely agreed about the continued value of rapid, at-home tests (for diagnosing people) and wastewater surveillance (for tracking COVID-19), they saw a lot of challenges ahead for both technologies. Here are some challenges that stuck out to me.

Challenges for rapid, at-home tests:

The public health emergency’s end won’t have an immediate impact on which COVID-19 tests are available, health policy researcher Christina Silcox from Duke University explained at the event. But, in the coming months, the FDA is likely to also end its emergency use authorization for COVID-19 diagnostics. As a result, companies that currently have tests authorized under this emergency will need to apply for full approval. Relatively few rapid tests are currently approved in this way, so the change could lead to fewer choices for people buying tests.

At the same time, it will become harder for many Americans to access rapid tests. After the federal emergency ends, private insurance companies will no longer be required to cover rapid tests. Some insurance providers might still do this (especially if large employers encourage it), said Amy Kelbik from McDermott+Consulting, but it will no longer be a universal option. At the same time, Medicare will stop covering rapid tests; Medicaid coverage will continue through fall 2024.

In light of these federal changes, state health officials at the ASU event talked about a need for continued funding to support rapid test distribution from state and local agencies. “Testing will continue to inform behavior, but will become drastically less available,” said Heather Drummond, testing and vaccine program leader at the Washington State Department of Health. Washington has led a free test distribution program, but it’s slated to end with the conclusion of the federal health emergency, Drummond said; she’d like to see services like this continue for the people who most need free tests.

Drummond and other health officials also discussed the challenges of educating people about how to interpret their test results, as COVID-19 guidance becomes less widely available. The vast majority of rapid, at-home test results are not reported to public health agencies—and, based on the event’s speakers, this isn’t a problem health agencies are particularly interested in devoting resources to solving right now. But as rapid tests become the default for diagnosing COVID-19, continued outreach will be needed on how to use them.

Also, as I’ve written before, some PCR testing infrastructure should still be maintained, for cases when someone needs a more definitive test result or wants documentation in case of long-term symptoms. PCR test access will likely get even worse after the federal health emergency ends, though, as insurance plans will also stop covering (or cover fewer costs for) these tests.

Challenges for wastewater surveillance:

Overall, wastewater surveillance is the best source for community-level COVID-19 data, speakers at the ASU event agreed. Official case numbers represent significant undercounts of true infections, and hospitalizations (while more reliable) are a delayed indicator. Wastewater data are unbiased, real-time, population-level—and the technology can be expanded to other common viruses and health threats, health officials pointed out at the event.

But wastewater surveillance is still very uneven across the U.S. It’s clear just from looking at the CDC’s map that some states have devoted resources to detailed wastewater testing infrastructure, with a testing site in every county—while others just have a handful of sites. Funding uncertainty likely plays a role here; speakers at the event expressed some confusion about the availability of CDC funds for long-term wastewater programs.

The CDC’s wastewater surveillance system has also faced challenges with standardizing data from different testing programs. And, at state and local agencies, health officials are still figuring out how to act on wastewater data. Agencies with more robust surveillance programs (such as Massachusetts, which had two officials speak at the ASU summit) may be able to provide success stories for other agencies that aren’t as far along.

Broader testing challenges:

For diagnostic company leaders who spoke at the event, one major topic was regulatory challenges. Andrew Kobylinski, CEO and co-founder of Primary.Health, said that the FDA’s test requirements prioritize highly accurate tests, even though less sensitive (but easier to use) tests might be more useful in a public health context.

Future COVID-19 tests—and tests for other common diseases—may need a new paradigm of regulatory requirements that focus more on public health use. At the same time, health agencies and diagnostic companies could do more to collect data on how well different test options are actually working. While it’s hard to track at-home tests on a large scale, more targeted studies could help show which tests work best in specific scenarios (such as testing after an exposure to COVID-19, or testing to leave isolation).

Company representatives also talked about financial challenges for developing new tests, particularly as interest in COVID-19 dies down and as recession worries grow this year. While a lot of biotech companies dove into COVID-19 over the last three years, they haven’t always received significant returns on their investments. For example, Lucira, the company behind the first flu-and-COVID-19 at-home test to receive authorization, recently filed for bankruptcy and blamed the long FDA authorization process.

Mara Aspinall, the ASU event’s moderator and a diagnostic expert herself, ended the event by asking speakers whether COVID-19 has led to lasting changes in this industry. The answer was a resounding, “yes!” But bringing lessons from COVID-19 to other diseases and health threats will require a lot of changes—to regulatory processes, funding sources, data collection practices, and more.

More testing data

-

Sources and updates, March 5

- FDA authorizes joint COVID/flu rapid test, but there’s a catch: Late last week, the FDA issued emergency use authorization to the U.S.’s first at-home, rapid test capable of detecting both COVID-19 and the flu. This could be a really useful tool for people experiencing respiratory symptoms, since COVID-19 and flu can appear so similar. But you might not be seeing this test on pharmacy shelves anytime soon: Lucira Health, the test’s manufacturer, just declared bankruptcy. And the company actually blamed FDA authorization delays for contributing to its financial situation, as it had produced supplies anticipating a fall/winter sale of tests. Brittany Trang at STAT News reported on the situation; read her story for more details.

- COVID-19 surveillance stressed out essential workers: For a new report, the nonprofit Data & Society interviewed 50 essential workers from meatpacking and food processing, warehousing, manufacturing, and grocery retail industries about their experiences with COVID-19 surveillance efforts, like temperature checks and proximity monitoring. Overall, workers found that these surveillance measures added time and stress to the job but did not actually provide information about COVID-19 spread in their workplaces. (Companies often cited privacy concerns as a reason not to share when someone got sick, according to the report.) The report shows how health data often doesn’t make it back to the people most impacted by its collection.

- Vaccinations vs. Long COVID meta-analysis: A new paper published this week in the BMJ examines how COVID-19 vaccination impacts Long COVID risk. The researchers (at Bond University in Australia) performed a meta-analysis, compiling results from 16 prior studies. While the studies overall showed that vaccination can decrease risk of getting Long COVID after an infection (and may reduce symptoms for patients already sick with Long COVID), the studies were too different in their methodologies to actually allow for “any meaningful meta-analysis,” the authors noted. To better study this question, more rigorous clinical trials are needed, the researchers wrote.

- Tracking Long COVID with insurance data: Another notable Long COVID paper, published this week in JAMA Health Forum: researchers at the insurance company Elevance Health compared health outcomes for about 13,000 people with post-COVID symptoms compared to 27,000 who did not have symptoms. The researchers found that, in the one year following acute COVID-19, Long COVID patients had higher risks for several health outcomes, including strokes, heart failure, asthma, and COPD; people in the post-COVID cohort were also more likely to die in that year-long period. I expect insurance databases like the one used in this paper may become more common Long COVID data sources. Also, see Eric Topol’s Substack for commentary.

- FDA committee recommends RSV vaccine applications: Finally, a bit of good news on the “other respiratory viruses” front: the FDA’s vaccine advisory committee has recommended the agency move forward with two applications for RSV vaccines. Major pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) have been working on RSV vaccine options; while early data appear promising, clinical trials on both vaccines have found potentially concerning safety signals. The trial populations have been relatively small, making these signals difficult to interpret right now but worthy of additional study. As usual, Katelyn Jetelina at Your Local Epidemiologist has provided a great summary of the FDA advisory committee meeting.

-

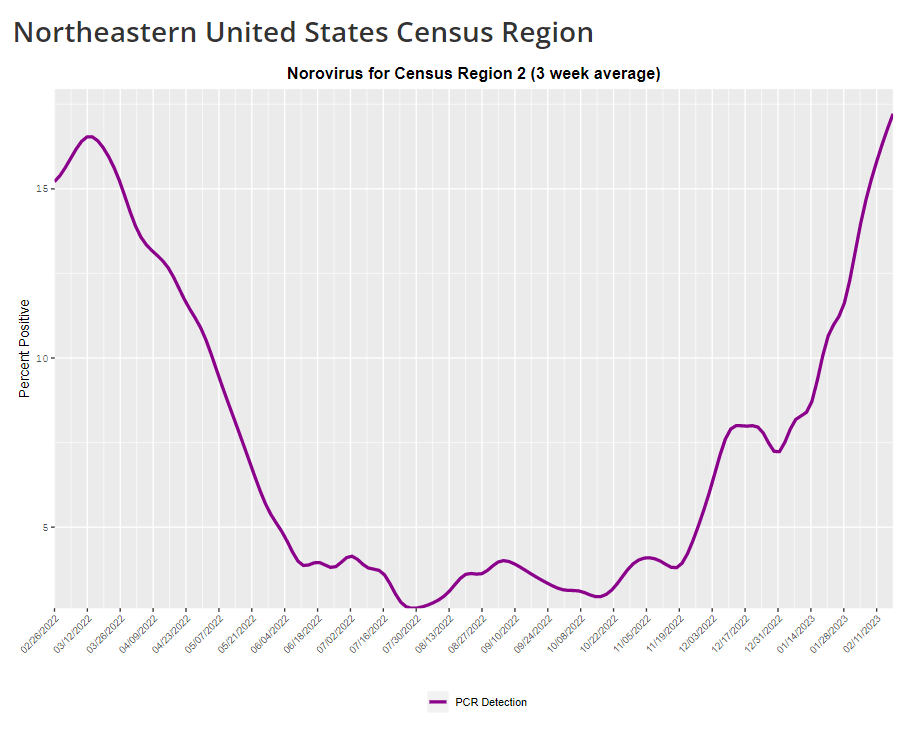

COVID-19 is inspiring improvements to surveillance for other common viruses

The CDC provides norovirus test positivity data from a select number of labs that report test results for this virus. Due to limited reporting, data are only available at the regional level. This week, I have a new story out in Gothamist and WNYC (New York City’s public radio station) about norovirus, a nasty stomach bug that appears to be spreading a lot in the U.S. right now. The story shares some NYC-specific norovirus information, but it also talks more broadly about why it’s difficult to find precise data on this virus despite its major implications for public health.

Reporting this story led me to reflect on how COVID-19 has revealed cracks in the country’s infrastructure for tracking a lot of common pathogens. I’ve written previously about how the U.S. public health system monitored COVID-19 more comprehensively than any other disease in history; the scale of testing, contact tracing, and innovation into new surveillance technologies went far beyond the previous standards. Now, people who’ve gotten used to detailed data on COVID-19 have been surprised to find out that such data aren’t available for other common pathogens, like the flu or norovirus.

It might feel disappointing to realize how little we actually know about the impacts of endemic diseases. But I choose to see this as an opportunity: as COVID-19 revealed gaps in public health surveillance, it inspired development in potential avenues to close those gaps. Wastewater surveillance is one big example, along with the rise of at-home tests and self-reporting mechanisms, better connectivity between health systems, mobility data, exposure notifications, and more.

Norovirus is a good example of this trend. Here are a few main findings from my story:

- Norovirus is a leading cause of gastrointestinal disease in the U.S., and is estimated to cause billions of dollars in healthcare and indirect societal costs every year.

- People who become infected with norovirus are often hesitant to seek medical care, because the symptoms are disgusting and embarrassing. Think projectile vomit, paired with intense diarrhea.

- Even when patients do seek medical care, norovirus tests are not widely available, and there isn’t a ton of incentive for doctors to ask for them. Testing usually requires a stool sample, which patients are often hesitant to do, one expert told me.

- The virus is not a “reportable illness” for the CDC, meaning that health agencies and individual doctors aren’t required to report norovirus cases to a national monitoring system. (So even when a patient tests positive for norovirus, that result might not actually go to a health agency.)

- The CDC does require health agencies and providers to report norovirus outbreaks (i.e. two or more cases from the same source), but national outbreak estimates are considered to be a vast undercount of true numbers.

- Even in NYC, where the city’s health agency does require reporting of norovirus cases, there’s no recent public data from test results or outbreaks. (The latest data is from 2020.)

As I explained in an interview for WNYC’s All Things Considered, the lack of a national reporting requirement and other challenges with tracking norovirus are linked:

It seems like the lack of a requirement and the difficulty of tracking kind-of play into each other, where it’s not required because it’s hard to track—but it’s also hard to track because it’s not required.

The lack of detailed data on pathogens like norovirus can be frustrating on an individual level, for health-conscious people who might want to know what’s spreading in their community so that they can take appropriate precautions. (For norovirus, precautions primarily include rigorous handwashing—hand sanitizer doesn’t work against it—along with cleaning surfaces and care around food.)

These data gaps can also be a challenge for public officials, as more detailed information about where exactly a virus is spreading or who’s getting sick could inform specific public health responses. For example, if the NYC health department knew which neighborhoods were seeing the most norovirus, they could direct handwashing PSAs to those areas. In addition, scientists who are developing norovirus vaccines could use better data to estimate the value of those products, and determine who would most benefit.

So, how do we improve surveillance for norovirus and other viruses like it? Here are a few options I found in my reporting:

- Wastewater surveillance, of course. The WastewaterSCAN project is already tracking norovirus along with coronavirus and several other common viruses; its data from this winter has aligned with other sources showing a national norovirus surge, one of the project’s principal investigators told me.

- Better surveillance based on people’s symptoms. The Kinsa HealthWeather project offers one example; it aggregates anonymous information from smart thermometers and a symptom-tracking app to provide detailed data on respiratory illnesses and stomach bugs.

- At-home tests, if they’re paired with a mechanism for people to report their results to a local public health agency. Even without a reporting mechanism, at-home tests could help curb outbreaks by helping people recognize their illness when they might be asymptomatic.

- Simply increasing awareness and access to the tests that we already have. If more people go to the doctor for gastrointestinal symptoms and more doctors test for norovirus, our existing data would get more comprehensive.

Are there other options I’ve missed? Is there another pathogen that might be a good example of common surveillance issues? Reach out and let me know.

-

Wastewater surveillance can get more specific than entire sewersheds

The first page from a comic about wastewater surveillance in K-12 schools, developed for UC San Diego’s SASEA program This week, I had a new article published in The Atlantic about how COVID-19 wastewater surveillance can be useful beyond entire sewersheds, the setting where this testing usually takes place. Sewershed testing is great for broad trends about large populations (like, an entire city or county), the story explains. But if you’re a public health official seeking truly actionable data to inform policies, it’s helpful to get more specific.

My story focuses on one wastewater testing setting that’s been in the news a lot lately: airplane bathrooms, from which researchers can identify new variants arriving with international travelers. But airplanes are far from the only place where specific wastewater surveillance can be valuable. Here are some of those other places, highlighting some information that I learned in reporting this story (but couldn’t fit in the final article).

K-12 schools

Early in the pandemic, colleges and universities became a hub for wastewater surveillance innovation. At campuses like Columbia University in NYC, researchers tested the sewage at individual dorms in order to determine exactly which students were getting sick—and take quick action, usually by requiring students at the infected dorm to get PCR-tested and quarantining the people who tested positive.

But the same technique can apply to schools with younger students. In late 2020, the University of California San Diego expanded its testing program to elementary schools, in an initiative called the Safer at School Early Alert System. The program started with 10 schools in the 2020-21 school year, then expanded to 26 in the 2021-22 year. Wastewater testing at specific sewershed points next to the schools led researchers to identify asymptomatic COVID-19 cases with high accuracy, program leader Rebecca Fielding-Miller told me.

The San Diego program isn’t alone: other public school systems have tried out building-level wastewater testing, usually in collaboration with nearby research groups. While the research projects tend to successfully show that wastewater surveillance can pick up infections, it’s challenging for school systems to get the funding to do these programs long-term. (Unlike universities, which are in total control of their funding, public schools need to rely on local governments).

As a consequence of these funding challenges, the San Diego program wasn’t renewed for the 2022-23 school year. “We really would have wanted to keep doing it, but funding ran out,” Fielding-Miller said.

Hospitals, other healthcare facilities

Much of the U.S.’s health strategy throughout the pandemic has focused on keeping hospitals from becoming overwhelmed—or at least helping hospitals weather COVID-19 surges. Wastewater surveillance can help accomplish this, by giving hospital administrators warnings about potential increased transmission; wastewater trends usually predict hospitalization trends by a week or more. And when wastewater surveillance is happening at hospitals themselves, these warnings can be really specific.

At NYC Health + Hospitals, the city’s public hospital system, administrators can get these warnings from wastewater testing at the system’s eleven hospitals. The surveillance program includes weekly tests for COVID-19, flu, and mpox (formerly called monkeypox), in collaboration with local researchers. The resulting data “gives us better situational awareness,” said Leopolda Silvera, a global health administrator at Health + Hospitals. If the health system notices a coming surge at one hospital, they can adjust resources accordingly—such as sending more staff to the emergency department.

The Health + Hospitals wastewater program has been running for about a year, Silvera said. At this point, it’s the only program she knows of that does building-level surveillance at hospitals. In the future, the hospital system might start testing for other pathogens and health threats like antimicrobial resistance.

Congregate facilities

Congregate facilities like nursing homes and senior living facilities can include a lot of vulnerable people who are at higher risk for severe COVID-19, all living in close quarters. As a result, this is another category of settings where it could be helpful to have building-level wastewater surveillance: facility administrators could learn quickly about upcoming surges and respond, by doing widespread PCR testing or instituting a temporary mask mandate.

The state of Maryland used to have a program doing exactly this, with a focus on correctional facilities throughout the state—particularly facilities housing the most vulnerable residents. The wastewater surveillance program ran through May 2022, at which point it “quietly ended,” according to local outlet the Maryland Daily Record. An initial $1 million in funding for wastewater testing in Maryland ran out; while the CDC National Wastewater Surveillance System picked up testing at wastewater treatment plants, no new entity was able to continue testing at the congregate living facilities.

According to the Daily Record, the building-level wastewater testing was incredibly helpful for informing COVID-19 measures at correctional facilities and helped keep cases down. I hope the Maryland program isn’t the last example we see of this testing in the U.S.

Large, communal workplaces

Early in the pandemic, some of the U.S.’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks happened at factories, particularly large food processing plants. People in these settings are often working in close quarters, easily able to infect each other—and when an outbreak happens, there are ramifications for both individual employees and the company’s business.

These large facilities could be another target for wastewater surveillance: if company administrators see a warning about rising COVID-19 from their buildings’ sewage, they could institute basic public health measures to curb the spread. Such is the strategy for some mine companies in rural Canada, which work with biotech company LuminUltra to test their wastewater. People often live and work at these sites, making them relatively closed settings for transmission.

At these locations, COVID-19 was previously “kind-of out of control, clinical testing was very reactive,” said Jordan Schmidt, director of product applications at LuminUltra. With wastewater testing, the mining companies can keep outbreaks “to a handful of people.” Fewer people get sick and there’s less interruption to business, he said.

Neighborhood-level testing

As public health agencies face lower budgets and overall lower awareness about COVID-19, some officials want to maximize their limited resources. If you only have the funding and staff for two mobile PCR testing sites this week, you’d want to make sure they go to a neighborhood where the testing would be most helpful, right?

The Boston Public Health Commission had this goal in mind when they launched a new neighborhood-level wastewater testing program, in collaboration with Biobot Analytics. The program includes testing twice a week at 11 sites across Boston, selected to provide good coverage of the city and also enable testing without too much disruption to traffic. While testing just started in January, the program is already helpful for identifying specific COVID-19 patterns, said Kathryn Hall, deputy commissioner for the health agency.

Boston’s program is focused on COVID-19 right now, but could expand to other diseases as needed, Hall said: “Now that we have the infrastructure in place, it allows us to be really be prepared and also to ask novel and interesting questions.”

Airplanes

Airplane surveillance fits into a slightly different category than the other settings I described here. When researchers test airplane wastewater, they aren’t seeking to get advanced warnings of new surges or inform public health policies. Instead, the goal is to track variants—with a focus on any new coronavirus mutations that might come into the U.S. from abroad. (Read the Atlantic story for more details on how this works!)

Other transportation hubs could be useful for tracking variants too, experts told me. This could mean large train stations, bus stations, shipping ports—any location that involves a lot of people moving from one place to another. After all, variants can evolve in the U.S. as easily as they can in other parts of the world.

Overall, the specific wastewater testing settings described here could be valuable pieces of expanding the U.S.’s overall surveillance network, along with the more-traditional sewershed testing. But all these testing sites need sustained funding to actually provide valuable data in the long run, something that could be in jeopardy as the federal public health emergency ends.

More wastewater surveillance

-

Looking ahead to the big COVID-19 stories of 2023

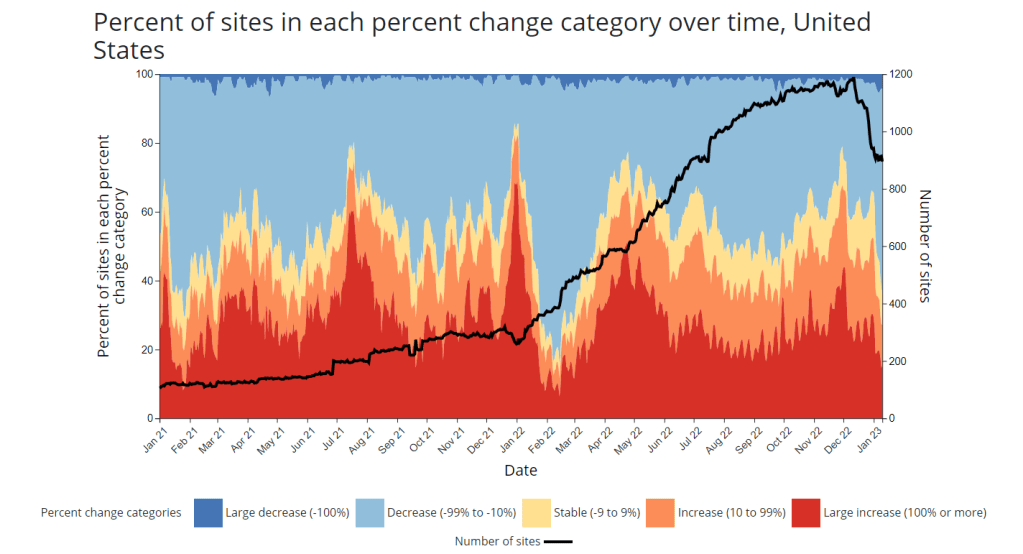

The number of sites reporting to the National Wastewater Surveillance System (see the black line) has declined in recent weeks. This may be a worrying trend going into 2023. It’s the fourth year of the pandemic. I’ve written this statement in a few pitches and planning documents recently, and was struck by how it feels simultaneously unbelievable—wasn’t March 2020, like, yesterday?—and not believable enough—haven’t we been doing this pandemic thing for an eternity already?

As someone who’s been reporting on COVID-19 since the beginning, a new year is a good opportunity to parse out that feels-like-eternity. So this week, I reflected on the major trends and topics I hope to cover in 2023—both building on my work from prior years and taking it in new directions.

(Note: I actually planned to do this post last week, but then XBB.1.5 took higher priority. Hence its arrival two weeks into the new year.)

Expansions of wastewater, and other new forms of disease surveillance

As 2022 brought on the decline of large-scale PCR testing, wastewater surveillance has proven itself as a way to more accurately track COVID-19 at the population level—even as some health departments remain wary of its utility. We also saw the technology’s use for tracking monkeypox, polio, and other conditions: the WastewaterSCAN project, for example, now reports on six different diseases.

This year, I expect that wastewater researchers and public agencies will continue expanding their use of this surveillance technology. That will likely mean more diseases as well as more specific testing locations, in addition to entire sewersheds. For example, we’re already seeing wastewater testing on airplanes. I’m also interested in following other, newer methods for tracking diseases, such as air quality monitors and wearable devices.

At the same time, these surveillance technologies will continue to face challenges around standardization and public buy-in. The CDC’s big contract with Biobot expires this month, and I’ve already noticed a decline in sites with recent data on the agency’s dashboard—will CDC officials and local agencies step in to fill gaps, or will wastewater testing become even more sporadic?

New variants, and how we track them

For scientists who track the coronavirus’ continued evolution, 2022 was the year of Omicron. We didn’t see all-new virus lineages sweeping the world; instead, Omicron just kept mutating, and mutating, and mutating. It seems likely that this pattern will continue in 2023, but experts need to continue watching the mutation landscape and preparing for anything truly concerning.

With declining PCR testing, public agencies and companies that track variants have fewer samples to sequence. (This led to challenges for the CDC team tracking XBB.1.5 over the holidays.) As a result, I believe 2023 will see increased creativity in how we keep an eye on these variants—whether that’s sequencing wastewater samples, taking samples directly from healthcare settings, increased focus on travel surveillance, or other methods.

Public health experts—and journalists like myself—also need to rethink how we communicate about variants. It’s no longer true that every new, somewhat-more-contagious variant warrants alarm bells: variants can take off in some countries or regions while having relatively little impact in others, thanks to differences in prior immunity, seasonality, behavior, etc. But new variants still contribute to continued reinfections, severe symptoms, Long COVID, and other impacts of COVID-19. Grid’s Jonathan Lambert recently wrote a helpful article exploring these communication challenges.

Long COVID and related chronic diseases

As regular readers likely know, Long COVID has been an increased topic of interest for me over the last two years. I’ve covered everything from disability benefits to mental health challenges, and am now leading a major project at MuckRock that will focus on government accountability for the Long COVID crisis.

Long COVID is the epidemic following the pandemic. Millions of Americans are disabled by this condition, whether they’ve been pushed out of work or are managing milder lingering symptoms. Some people are approaching their three-year anniversary of first getting sick, yet they’ve received a fraction of the government response that acute COVID-19 got. Major research projects are going in the wrong directions, while major media publications often publish articles with incorrect science.

For me, seeing poor Long COVID coverage elsewhere is great motivation to continue reporting on this topic myself, at MuckRock and other outlets. I’m also planning to spend more time reading about (and hopefully covering) other chronic diseases that are co-diagnosed with Long COVID, like ME/CFS and dysautonomia.

Ending the federal public health emergency.

Last year, we saw many state and local health agencies transition from treating COVID-19 as a health emergency to treating it as an endemic disease, like the many others that they respond to on a routine basis. This transition often accompanied changes in data reporting, such as shifts from daily to weekly COVID-19 updates.

This year, the federal government will likely do the same thing. POLITICO reported this week that the Biden administration is renewing the federal public health emergency in January, but will likely allow it to expire in the spring or summer. The Department of Health and Human Services has committed to telling state leaders about this expiration 60 days before it happens.

I previously wrote about what the end of the federal emergency could mean for COVID-19 data: changes will include less authority for the CDC, less funding for state and local health departments, and vaccines and treatments controlled by private markets rather than the federal government. I anticipate following up on this reporting when the emergency actually ends.

Transforming the U.S. public health system

Finally, I intend to follow how public health agencies learn from—or fail to learn from—the pandemic. COVID-19 exposed so many cracks in America’s public health system, from out-of-date electronic records systems to communication and trust issues. The pandemic should be a wakeup call for agencies to get their act together, before a new crisis hits.

But will that actually happen? Rachel Cohrs has a great piece in STAT this week about the challenges that systemic public health reform faces, including a lack of funding from Congress and disagreements among experts on what changes are necessary. Still, the window for change is open right now, and it may not be at this point in 2024.

More federal data

-

NYC’s wastewater program models the challenges facing local public health agencies

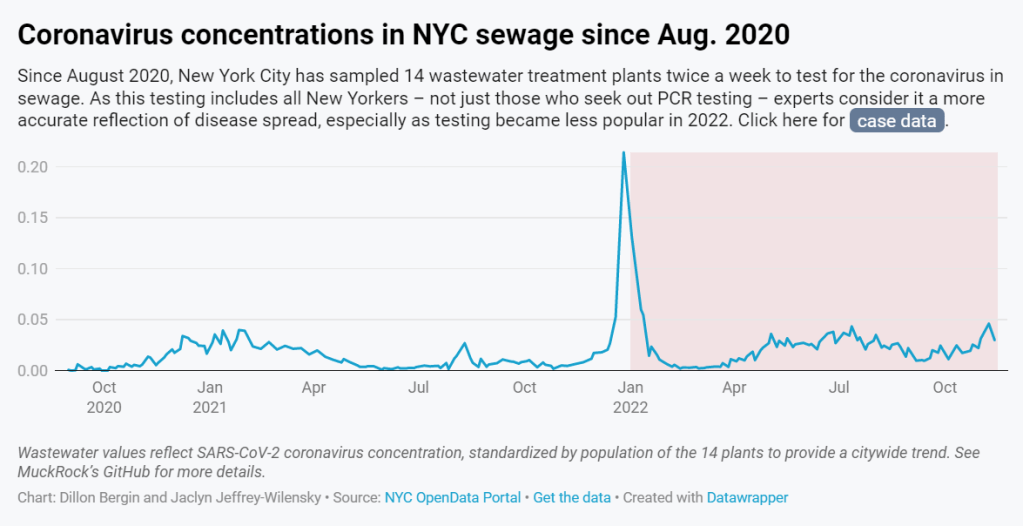

In 2022, wastewater data in NYC have more accurately reflected COVID-19 spread in the city than case data. See the full story (on MuckRock or Gothamist) for the interactive chart; links are below. My second big story this week is a detailed report about New York City’s wastewater surveillance program, highlighting its lack of transparency. You can read the story on Gothamist and/or on MuckRock. I’m particularly excited to share this one with NYC-based readers, as it uncovers a public program that’s been running under our feet for nearly three years.

Longtime readers might remember that, back in April, I noticed that NYC wastewater data had disappeared from the CDC’s national dashboard. And the city’s data stayed unavailable even when other locations (which were similarly interrupted by the CDC’s switch between wastewater contractors) resumed reporting to the dashboard.

That observation piqued my curiosity about how, exactly, NYC agencies are testing our wastewater—and what they’re doing with the data. So, I started investigating, with the support of MuckRock and Gothamist/WNYC. My project eventually revealed the answers to my questions: while NYC has set up an impressive, novel program to test all 14 city wastewater treatment plants for COVID-19, the health department doesn’t appear to be taking advantage of these results.

In a joint statement, NYC’s health and environmental protection agencies said that they still see wastewater surveillance as a “developing field” and are skeptical about its utility for public health. Even though NYC’s program has been running since early 2020 and cost over $1 million. And even though other wastewater programs across the U.S. and internationally have demonstrated the potential of this type of data.

Here are the story’s main findings, as drafted for MuckRock’s version of the article:

- New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection created a brand-new program to test city wastewater for COVID-19 in 2020, working with limited lab equipment and personnel to sample from 14 sewage treatment plants across the city. In doing so, the city brushed off assistance offered from “multitudes of academics” and private sector researchers, and set up its program in-house. It has cost more than $1 million over the past three years.

- But the city didn’t publicly post any wastewater data until January 2022, almost two years after testing started. Unlike other large cities, such as Boston, New York City lacks a public dashboard for wastewater data. The city’s data available on dashboards run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York State are often delayed by a week or more, making it less useful for New Yorkers seeking advanced warning about potential new surges.

- In other parts of the U.S. — and at Columbia University in uptown Manhattan — wastewater surveillance is used for public health strategies, such as encouraging people to get PCR tests or sending extra resources to hospitals before a surge. However, New York City’s health and environmental agencies say they still consider wastewater research a “developing field” and aren’t using it for policy decisions.

- In response to our questions, city health and environment agency officials argued that wastewater results “do not generally provide a complete picture” of how COVID-19 is spreading and said, unlike in other parts of the country, trends in city wastewater data tend to align with case counts rather than predicting them. But wastewater has shown a higher level of COVID-19 spread than PCR testing, as the latter became less available in 2022, according to Gothamist and MuckRock analyses. This pattern suggests that the sewage numbers may more accurately reflect actual disease patterns.

- A bill introduced to the New York City Council in August would make the wastewater surveillance program permanent, expand it to other public health threats as needed, and require the health department to report data on a public dashboard.

For readers outside NYC, I think this story provides an informative case study of the hurdles that wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 (and other diseases) will need to clear.

First, you have the resource challenges. If the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, which oversees the largest municipal water network in the country, had a hard time getting equipment and personnel for testing—imagine the challenges facing small, rural public health departments.

Next, after testing is set up, you have to interpret the data. NYC’s health department seems to be somewhat stuck on this step, with no public dashboard and its insistence that city residents should look at clinical case data—which we know are a significant undercount of true infections—rather than wastewater data. To be fair, wastewater data are new terrain for public health experts, with a lot of analytical issues. (See my MuckRock/FiveThirtyEight story from the spring for more details on this.)

And finally, you have to communicate the data. How do you share wastewater results with the public in a way that is clear, real-time, local—and acknowledging necessary caveats? This is a tough challenge that health agencies across the U.S. are just starting to tackle, in tandem with the private companies that work on wastewater analysis.

As I said in the radio story accompanying my piece, I hope that, someday, we can get wastewater surveillance updates as easily and regularly as we get weather updates. That future feels a long way off right now, but I intend to keep reporting on the journey in 2023.

If you live somewhere with a thriving (or faltering) wastewater surveillance program, reach out and tell me about it!

More on wastewater data