- COVID-19 polling data from Axios/Ipsos: During the workshop I led at NICAR last weekend, one attendee (who works at the market research company Ipsos) recommended that journalists and researchers interested in Long COVID data should check out the Axios/Ipsos polling project to track American attitudes on COVID-19. Recent iterations of the poll have included questions about Long COVID, and the polling results are broken out by demographics (age, race, houeshold income). The surveys ask many other COVID-19 questions as well, such as attitudes about masking. To access the data, you can download PDFs from the Ipsos site or spreadsheets from Roper.

- CDC provides guidance for Long COVID deaths: The CDC National Center for Health Statistics has started to add information about Long COVID to its guidance for death certificates, following a report that the agency published in December about deaths from Long COVID. The guidance now explains that SARS-CoV-2 “can have lasting effects on nearly every organ and organ system of the body weeks, months, and potentially years after infection,” and can contribute to premature death months or years after a patient’s original infection. For context, see MuckRock’s report on Long COVID deaths from December.

- Long COVID gastrointestinal symptoms: Ziyad Al-Aly and his team at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System have a new paper in Nature about long-term gastrointestinal symptoms following COVID-19. Using the VA electronic health records database, the researchers compared 150,000 people who’d had COVID-19 to millions of controls. They found people with COVID-19 had elevated risks of many gastrointestinal disorders (including acid-related illness, intestinal disorders, pancreatitis, and more) in the year following their acute cases, compared to the controls. GI symptoms have long been an under-publicized aspect of COVID-19 and Long COVID.

- Clinical trial for Long COVID shows promising results: And one more Long COVID study: researchers at the University of Minnesota examined the potential for three common medications to lower risk of Long COVID. This study was a blinded, randomized control trial—the gold standard of medical research. One of the drugs tested, metformin (which is a common medication for type 2 diabetes), led to a significantly lower risk of Long COVID compared to the placebo. The study hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, but it shows promising results for metformin as a potential Long COVID treatment option.

- Examining trust in public health agencies: Another new paper, published this week in Health Affairs, shares results from a survey of about 4,200 U.S. adults (a nationally representative sample) about trust in public health agencies. The survey suggested that trust in federal agencies is connected to perceptions of scientific expertise, while trust in state and local agencies is more tied to “perceptions of hard work, compassionate policy, and direct services.” Survey respondents who reported the least trust in public health cied concerns about political influence, private sector influence, inconsistency, and excessive restrictions.

- Some parents lied about children’s COVID-19 status: One more notable survey study, published this week in JAMA Network Open: researchers at Middlesex Community College (in Connecticut) and University of Utah Health, among other collaborators, surveyed a group of 1,700 U.S. parents about COVID-19 protective measures for their children. The study found about 26% of respondents reported lying about or misrepresenting their child’s COVID-19 status in order to break quarantine rules. Common motivations for this behavior were wanting to “exercise personal freedom as a parent,” not being able to miss work or other responsibilities, and wanting kids to have normal experiences. The results suggest “a serious public health challenge” for continued COVID-19 outbreaks and other infectious diseases, the paper’s authors write.

- Maternal mortality during the pandemic: MuckRock (where I work part-time) has published new analysis showing a significant increase in maternal deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on CDC mortality data. The death rate for women ages 15 to 44 went from about 29 deaths per 100,000 births in 2019 to 46 deaths per 100,000 births in 2021. Death rates were significantly higher for Black women and in states with more restrictive policies on maternal healthcare. You can find the full analysis (including a selection of state-level data) here.

Tag: death certificates

-

Sources and updates, March 12

-

New CDC report vastly underestimates deaths with Long COVID

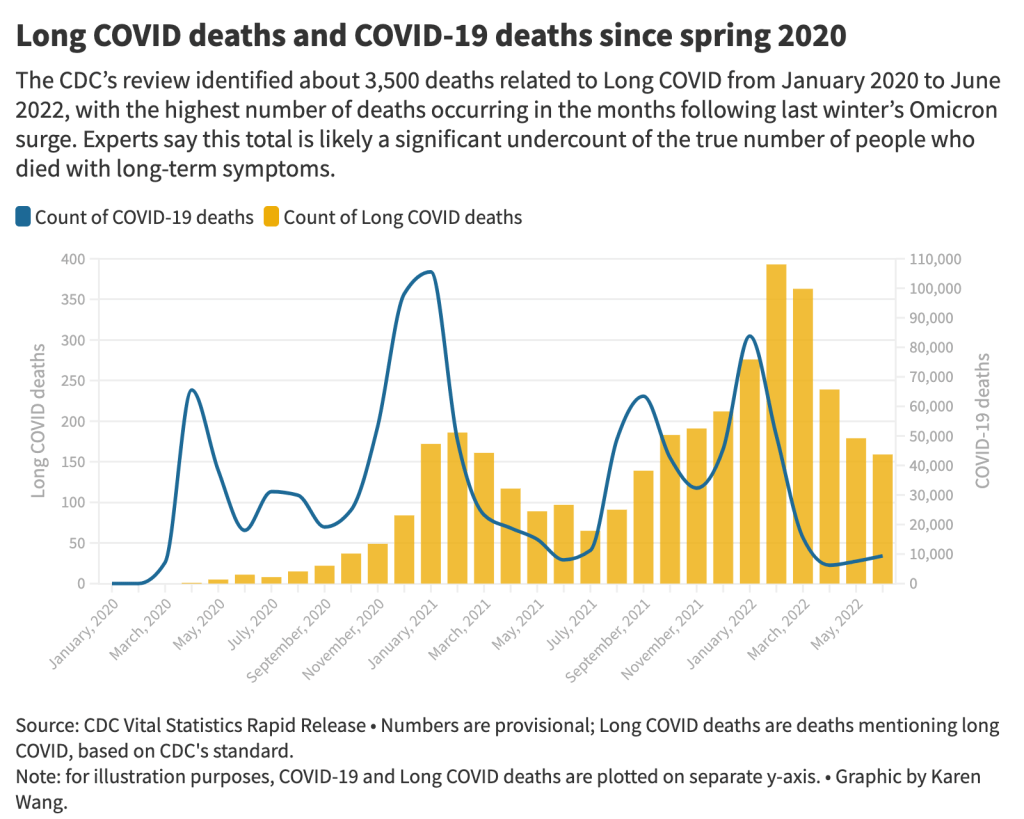

The 3,500 Long COVID-related deaths identified by the CDC’s review of death certificates are likely a significant undercount of mortality caused by this condition, experts say. Chart by Karen Wang; see the interactive version on MuckRock. On Wednesday, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NHCS) released a major report on deaths from Long COVID. To identify a small (but significant) number of deaths, NCHS researchers searched through the text of death certificates for Long COVID-related terms. Their study demonstrates how bad our current health data systems are at capturing the results of chronic disease.

My colleagues and I at MuckRock did a similar analysis to the CDC’s, searching death certificate data that we received through public records requests and partnerships in Minnesota, New Mexico, and counties in California and Illinois. You can read our full story here and explore the death certificate data we analyzed on GitHub.

Here are the main findings from both analyses:

- The CDC study is an important milestone in recognizing the reality of Long COVID: this is a serious, chronic disease that can lead to death for some patients. It’s not just an outcome of acute COVID-19.

- From its national death certificate search, NCHS identified 3,544 deaths with Long COVID as a cause or contributing factor. This is almost certainly a major undercount, experts told me (and told other reporters who wrote about the study.)

- This number is an undercount because we’re essentially seeing two poor-quality data systems intersect. Long COVID is undercounted in clinical settings because we lack standard diagnostic tools and widespread medical education about it—most doctors wouldn’t think to put it on a death certificate as a result. And the U.S.’s death investigation system is uneven and under-resourced, leading to inconsistencies in tracking even well-known medical conditions.

- On top of these problems, when Long COVID is diagnosed, it tends to be among people who had severe cases of acute COVID-19 followed by difficulty recovering, experts told me. David Putrino and Ziyad Al-Aly, two leading Long COVID researchers, both pointed to the NCHS’s trend towards identifying Long COVID deaths among older adults (over age 75) as an example of this pattern in action, since this group is at higher risk for more severe acute symptoms.

- The NCHS count of deaths thus misses Long COVID patients with symptoms similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which often arises after a milder initial case. It also misses people who have vascular impacts from a COVID-19 case, like a premature heart attack or stroke months after infection—something Al-Aly and his team have studied in depth. And, crucially, the NCHS count misses people who died from suicide, after suffering from severe mental health consequences of Long COVID.

- While the NCHS count of Long COVID deaths is far too low to be accurate, the researchers did find more deaths as the pandemic went on—with the highest number in February 2022, following the first Omicron surge. This pattern could suggest increased recognition of Long COVID among the medical community.

- The NCHS primarily identified Long COVID deaths among white people, even though acute COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted people of color in the U.S. Experts say this mismatch could reflect gaps in access to a diagnosis and care for Long COVID: if white people are more likely to be seen by a doctor who can accurately diagnose them, they will be overrepresented in Long COVID datasets. Putrino called this “a health disparity on top of a health disparity.”

- MuckRock’s analysis of death certificate data in select states similarly found that most deaths labeled as Long COVID were among seniors and white people. The trends varied by state, though, reflecting differences in populations and in local death reporting systems. For example in New Mexico, which has a statewide medical examiner’s office (rather than a looser system of county coroners), three-fourths of the Long COVID deaths were among Hispanic or Indigenous Americans.

- Our story also includes details about the RECOVER initiative’s autopsy study, which aims to use extensive postmortem testing on people who might have died from acute COVID-19 or Long COVID to identify biological patterns. Like the rest of RECOVER, this study is moving slowly and facing logistical challenges: about 85 patients have been enrolled so far, an investigator at New York University said.

Overall, the NCHS study suggests an urgent need for more medical education about Long COVID, especially as the CDC works to implement a new death code specific to this chronic condition. We also need broader outreach about the consequences of Long COVID. To quote from the story:

“Institutions like the CDC should do more to educate people about the long-term problems that could follow a COVID-19 case, said Hannah Davis, the patient researcher. “We need public warnings about risks of heart attack, stroke and other clotting conditions, especially in the first few months after COVID-19 infection,” she said, along with warnings about potential links to conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer’s and cancer.

And we need other methods of studying Long COVID outcomes that don’t rely on a deeply flawed death investigation system. These could include studies of excess mortality following COVID-19 cases, Long COVID patient registries that monitor people long-term, and collaborations with patient groups to track suicides.

For any reporters and editors who may be interested, MuckRock’s story is free for other outlets to republish.

More Long COVID reporting

-

The “one million deaths” milestone fails to capture the pandemic’s true toll

This week, many headlines declared that the U.S. has reached one million COVID-19 deaths. While a major milestone, this number is actually far below the full impact of the pandemic; looking at excess deaths and demographic breakdowns allows us to get closer.

NBC News was the first outlet to make this declaration, announcing that its internal COVID-19 tracker had hit the one million mark. Other trackers, including the CDC itself, have yet to formally reach this number, but major publications still jumped on the news cycle in anticipation of this milestone. (Various trackers tend to have close-but-differing COVID-19 counts due to differences in their methodologies; Sara Simon wrote about this on the COVID Tracking Project blog back when the official death toll was 200,000.)

But the recent articles about “one million deaths” fail to mention that the U.S. actually reached this milestone a long time ago. This is because the official count only includes the deaths formally logged as COVID-19, in which the disease was listed on a death certificate or diagnosed before a patient passed. Such a count fails to include deaths that were tied to COVID-19, but never proven with a positive test result, or deaths that were indirectly linked to the pandemic for a myriad of reasons.

To get closer to the pandemic’s true toll, demographers use a metric called excess deaths: the number of deaths that occurred in a given region and time period above what would be expected for that region and time period. Experts calculate that “expected death” number with statistical models based on patterns from previous years.

In total, the U.S. has reported 1,118,540 excess deaths between early 2020 and last month. 221,026 of those deaths have not been formally tied to COVID-19. According to a new World Health Organization report, the U.S. was already close to one million COVID-related deaths by December 2021.

To give a more specific example: in the U.S., in the week ending January 22, 2022, CDC analysts estimated that 61,303 deaths would have occurred if there were no COVID-19 pandemic. But actually, a total of 85,179 deaths occurred in the country that week. The difference between the observed and expected values, 23,876, is the excess deaths for this week.

I selected the week ending January 22 as an example here because it has one of the highest excess death tolls of any week in the last two years. This week marked the peak of the Omicron surge, a variant that many U.S. leaders called “mild” and dismissed without instituting further safety measures.

During this week, the CDC reports 21,130 official COVID-19 deaths. That suggests most of the excess deaths in this week, the deaths which occurred over pre-pandemic expectations, were directly caused by the virus.

But what about the 2,746 deaths that weren’t? How many of these deaths were also caused by COVID-19, but in patients who were never able to access a PCR test? How many occurred in counties like Cape Girardeu, Missouri, where coroner Wavis Jordan claimed his office “doesn’t do COVID deaths” and refuses to put the disease on a death certificate without specific proof?

And how many deaths resulted from people being unable to access the healthcare they needed because hospitals were full of COVID-19 patients, or people dying in car accidents during an era of less road safety, or people dying of opioid overdoses brought on by increased stress and financial instability?

Answering these questions takes a lot of in-depth reporting, which I know well because the Documenting COVID-19 team has been doing our best to answer them through our (award-winning!) Uncounted investigation.

As we’ve found, every state—and in some cases, every county—has a unique system for investigating and reporting deaths, especially those linked to the pandemic. In some places, coroners or medical examiners are elected officials who face political pressure to report COVID-19 deaths in a particular way. In others, they face chronic underfunding and a lack of training, leaving them to work long hours in an attempt to produce accurate numbers.

You can see the resource difference when comparing officially-reported COVID-19 deaths to excess deaths by state or county. Some states, like those in New England, have COVID-19 death numbers that closely match or even exceed their excess death numbers; medical examiners in these states have centralized death reporting systems and a lot of resources for this process, reporting by my colleague Dillon Bergin showed.

Other states, like Alaska, Oregon, and West Virginia, have officially logged fewer than three in four excess deaths as COVID-19 deaths. Such a number may signal that a state is failing to properly identify all of its COVID-19 fatalities.

For more granular data on this topic, I recommend reading the work of Andrew Stokes and his team at Boston University. Andrew is the Documenting COVID-19 project’s main academic collaborator on Uncounted; his team just shared their latest county-level excess death estimates in a preprint. (County-level data are also available in the Uncounted project’s GitHub repository.)

Excess deaths can also show how the pandemic continues to hit disadvantaged Americans harder. In 2020, COVID-19 death rates (i.e. deaths per 100,000 people) for Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic Americans were higher than the rates for White Americans; in 2021, some of these disparities actually got worse despite the broad availability of vaccines and other mitigation measures. Non-white groups also saw all-cause mortality (not just COVID-19 deaths) increase more from 2019 in both 2020 and 2021, compared to white Americans.

Please note, the chart below shows crude death rates, which don’t account for differences in age breakdowns between race and ethnicity groups. For example, crude death rates for white Americans tend to be higher because white people generally live longer than people of color in the U.S., and more seniors have died of COVID-19. You can see the difference that ade-adjustment makes in the CDC charts here.

Why is it important to acknowledge and investigate these excess deaths, going beyond the reported COVID-19 numbers? At an individual level, family members who lost loved ones to COVID-19 find that diagnosis important; they can access FEMA aid for funerals, and can receive acknowledgment of how this one death fits into the broader pandemic.

And at the county, state, and national levels, looking at excess deaths allows us to see a full picture of how COVID-19 has affected us. Experts say that inaccurate COVID-19 death numbers can create a negative feedback loop: if your community has a too-low toll, you may not realize the disease’s impact, and so you may be less likely to wear a mask or practice other safety precautions—contributing to more deaths going forward.

As a data journalist, sharing these statistics and charts is my way of acknowledging the one million deaths milestone, and all of the uncounted deaths that are not included in it. But this pales in comparison to actual stories shared by family members and friends of those who have died in the last two years.

To read these stories, I often turn to memorial projects like Missing Them (from THE CITY), which captures names and stories of over 2,000 New Yorkers who died from COVID-19. Social media accounts like FacesOfCOVID also share these stories. And if any COVID-19 Data dispatch readers would like to share a story of someone they lost to this disease, please email me at betsy@coviddatadispatch.com; I would be honored to share your words in next week’s issue.

More federal data

-

Peru audits deaths data, shows the value of excess deaths

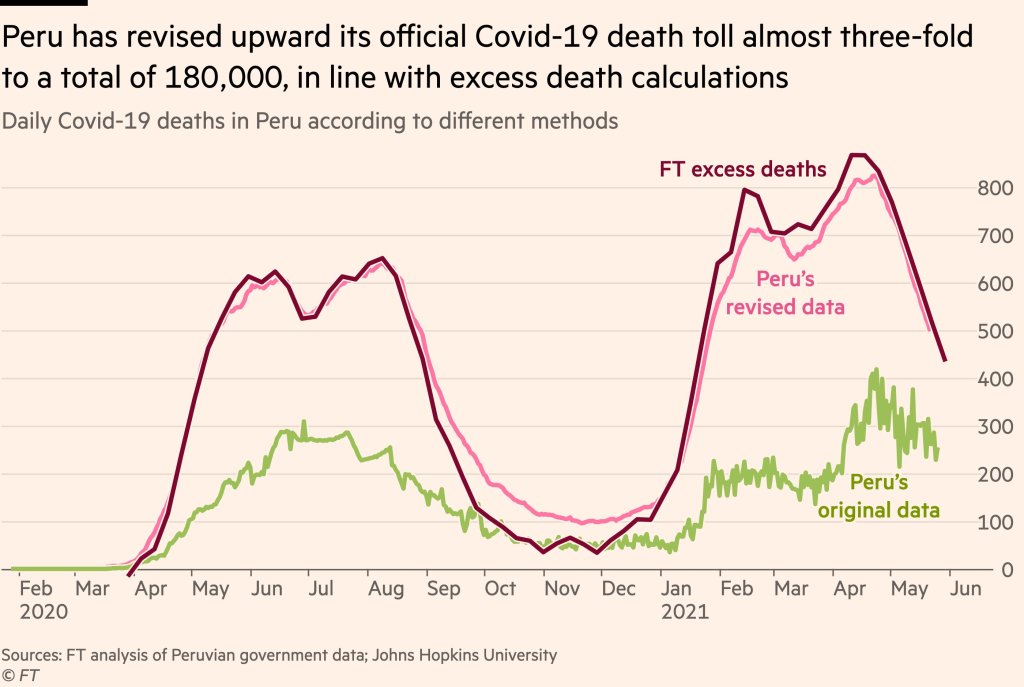

Peru’s revision led the country’s official death count to match its estimated excess deaths. Source: Financial Times.. Excess deaths are those deaths that occur above a region’s past baseline. Data scientists calculate the metric by determining the average deaths for a country or region over a period of several years—then comparing this past average to the deaths that occured in the current year.

The deaths occurring in the current year above that past average are the excess deaths. In New York City during the spring 2020 surge, for example, about four times more people were dying each week compared to the same time period in previous years.

During the pandemic, excess deaths have become a useful way for scientists to estimate the true toll of COVID-19. Especially during the earlier months of 2020, limited access to testing meant that many people who became infected with the coronavirus were not able to get the positive test required for their illness (or death) to actually be counted as a case. (In the U.S., this recording gap is currently causing issues for families who lost loved ones to COVID-19 early in the pandemic and are now seeking federal aid.)

Plus, the pandemic caused hospital systems to shut down and inspired widespread hesitancy for anyone seeking medical care for a non-COVID reason. The death of someone who had a heart attack and couldn’t get a hospital bed because of COVID-19, for example, is not a COVID-19 death but was undoubtedly caused by the pandemic.

Excess deaths, as a metric, allow researchers to see how the pandemic has impacted a country or region—above the official COVID-19 death counts. And a recent audit from Peru provides new evidence for this metric’s value.

The country essentially audited its COVID-19 deaths data to address undercounting. Government officials checked thousands of death certificates from 2020, and added any COVID-related deaths to past totals—which previously only included those Peruvians who had positive PCR tests.

After the audit was complete, Peru’s COVID-19 death toll rose by almost three times—to 180,000 deaths. The country now has the highest official death rate in the world: one in every 177 people.

When plotted over time, Peru’s revised death data match closely with its excess deaths, as calculated by the Financial Times data team. This audit—and its match with excess deaths—shows that excess deaths do, in fact, show the true toll of COVID-19 in a country.

It’s also notable as the first time a country has done such an audit on a wide scale. Some states (such as Washington) have added COVID-19 deaths to their official counts periodically, as they process death certificate backlogs, but none have done anything on Peru’s level.

Future death certificate audits and excess death analyses may help us understand the true toll COVID-19 has taken on the U.S. and the world.