On October 1, a little over two weeks ago, I received an email from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s office.

The email invited me to download a new COVID-19 phone application, developed by the New York State Department of Health along with Google and Apple. The app, called COVID Alert NY, is intended to help New Yorkers contact trace themselves. (Side note: I am not entirely sure how Cuomo’s office got my email, but I suspect it has something to do with the complaints I left about his budget back in June.)

Here’s how Cuomo’s office describes the app:

COVID Alert NY is New York State’s official Exposure Notification App. This is a free smartphone app available to anyone 18+ who lives and/or works in New York. The app uses Bluetooth technology—not location data—to quickly alert users if they have been in close contact with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19. Once alerted, users can quickly protect themselves and others by self-quarantining, contacting their physician and getting tested.

The app is intended to fit into New York’s contact tracing efforts by automatically informing app users that they have been exposed to COVID-19 and prompting them to take the necessary precautions. It also features a sypmtom checker, which asks users to note if they have exhibited a fever, cough, or other common COVID-19 symptoms, and a page with the latest case and testing data for every county in New York.

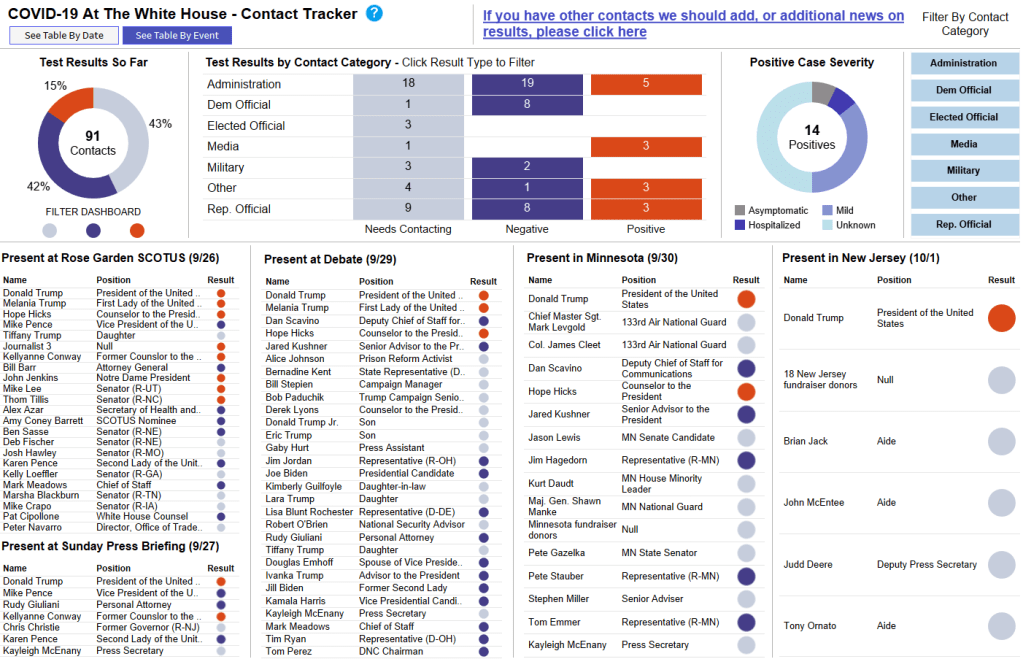

Contact tracing, or the practice of limiting disease spread by personally informing people that they have been exposed, has been a major method for controlling COVID-19 spread in other countries, such as South Korea. But in the U.S. the strategy is—like every other part of our nation’s COVID-19 response—incredibly patchwork. We have no national contact tracing app, much less a national contact tracing workforce, leaving states to set up these systems on their own.

Back in May, I researched and wrote an article for Stacker about this problem. I compared contact tracing targets, calculated by researchers at George Washington University, with the actual numbers of contact tracers employed in every state, compiled by the public health data project Test and Trace. GWU’s estimates started at a baseline 15 contact tracers per 100,000 people, then were adjusted based on COVID-19 trends in every state. Now, this story should be seen as a historical snapshot (the summer’s Sun Belt outbreaks hadn’t yet started when I wrote it), but it is telling to scroll through and see that, even several months into America’s COVID-19 outbreak, the majority of states had tiny fractions of the contact tracing workforces they needed to effectively trace new cases. New York, for example, had a reported 575 contact tracers employed, compared to an estimated need of over 15,000 contact tracers.

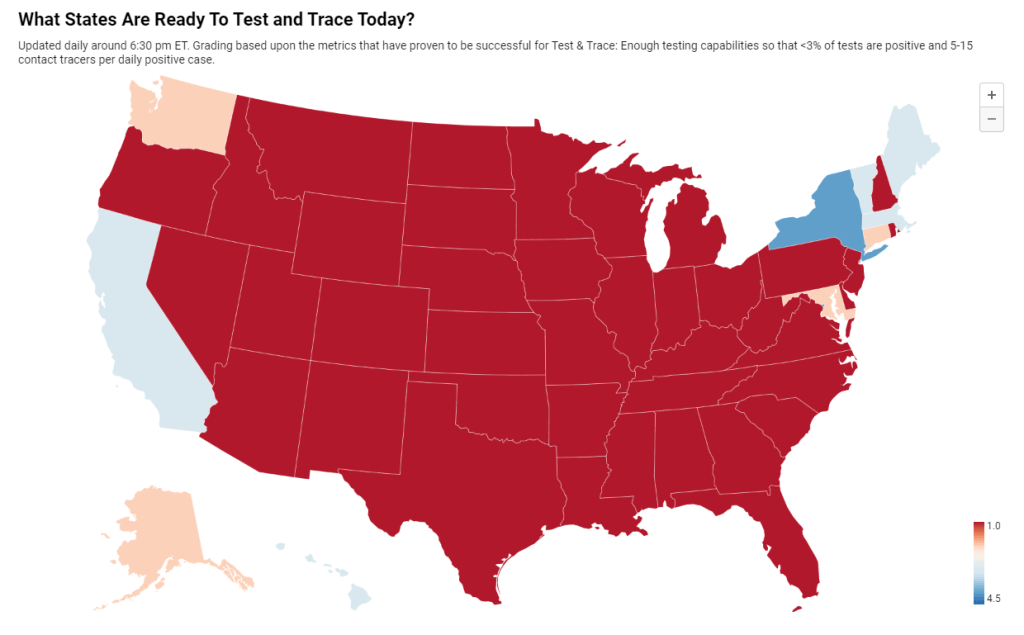

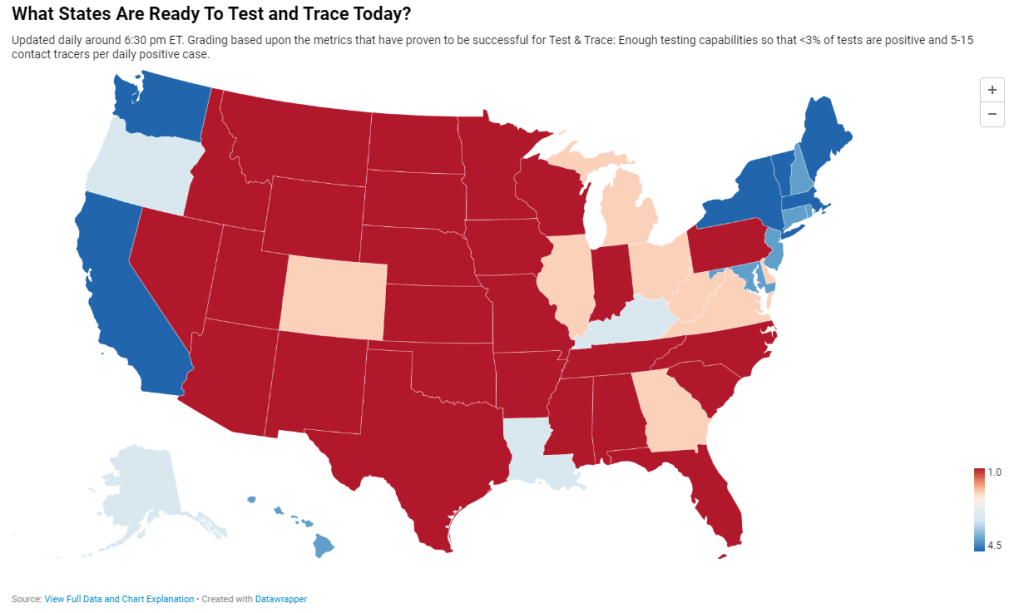

Today, many states are doing better. New York is up to 9,600 contact tracers, according to Test and Trace’s latset counts, and has planned to hire thousands more. This state, along with Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Vermont, and Washington D.C., has received high marks from Test and Trace’s scoring system, with 5 to 15 tracers employed for every new positive COVID-19 case. But all of these high-scoring states are in the Northeast, where COVID-19 outbreaks peaked in the spring. The Midwestern states currently seeing spikes, such as Wisconsin and Missouri, all rank far lower on their preparedness to trace new cases. (See the screenshot above.)

Meanwhile, actual data on the efficacy of these contact tracers are difficult to come by. To continue using New York as an example: since the application’s release on October 1, New York’s Department of Health has not released any data on how many people have downloaded the application, much less how many positive cases have been logged or how many contacts have been traced. Data have neither been mentioned in Cuomo’s press releases nor have they appeared on the state’s COVID-19 dashboard.

According to tech website 9to5Mac, as of October 1, 11 states had registered contact tracing apps with Google and Apple’s exposure notification technology. These states include Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wyoming, as well as New York. Six more states have apps in development.

A brief analysis by yours truly found that, of those 11 states with contact tracing apps, only four post contact tracing data: Delaware, New Jersey, North Dakota, and Wyoming. Delaware and New Jersey both have dedicated data pages detailing the share of COVID-19 cases which have successfully participated in the state’s contact tracing efforts (57% and 71%, respectively). North Dakota and Wyoming both post statistics on their cases’ source of COVID-19 exposure, including such categories as “contact with a known case,” “community spread,” and “travel”; these data must be sourced from contact tracing investigations. 11.1% of North Dakota’s cases and 27.1% of Wyoming’s cases have an exposure source listed as “unknown” or “under investigation,” as of October 18. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania and North Carolina have both posted statistics on their contact tracing workforces, but no data on the results of these workforces’ efforts.

Other states without registered apps may also be posting contact tracing data. But it is still a notable discrepancy that, among the states that have systematic contact tracing technology, tracing results are lacking. Compare these states to South Korea, which at the height of its outbreak publicly posted demographic information and travel histories for individual COVID-19 cases in alerts to surrounding communities. South Korea’s approach has faced criticism, however, for reporting private information about people who tested positive.

And that brings me to the biggest weakness for American contact tracing: lack of public trust. Americans, more than residents of other nations, tend to be concerned about personal privacy and, as a result, are more wary of speaking to strangers on the phone or using an application that sends their data to the government, even if all those data are anonymized. Olga Khazan explained this issue in an article for The Atlantic, published in late August:

Still, contract tracing depends on trust, and many Americans don’t trust the government enough to give up their contacts or follow quarantine orders. Of the 121 agencies Reuters surveyed, more than three dozen said they had been hindered by peoples’ failure to answer their phone or provide their contacts. About half of the people whom contact tracers call don’t answer the phone, because they don’t want to talk with government representatives, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said during a June news conference.

Black and Hispanic or Latino communities are particularly likely to distrust the government and avoid contact tracers’ calls. This attitude makes sense, given how both America’s government and medical systems are inexorably tied to racist histories. But for the public tracers hoping to help these communities—which have been disproportionately impacted COVID-19—it’s another barrier to stopping the virus’ spread.

Even I, as someone who understands more about the need for contact tracing than the average American, am wary about using New York’s COVID Alert app. The app asks me to turn on both Bluetooth and location data, and even though COVID Alert purports to be anonymous, Twitter, Instagram, and other applications have made no such promises. So far, I have been using the application when I go to the park, grocery shop, or ride the subway, but for the vast majority of my days it sits dormant on my phone.

And of course, I have to wonder: where was this app in March, when the city shut down and my neighborhood filled with ambulance sirens? Like most other parts of America’s COVID-19 response, contact tracing has been scattered and difficult to evaluate, but the data we do have indicate that most states are doing too little, too late.